Home | Category: New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut)

NEW KINGDOM RULERS (CA. 1550–1070 B.C.)

Karnak King List Drawing 1

New Kingdom Rulers (ca. 1550–1070 B.C.)

Dynasty 18, ca. 1550–1295 B.C.

Ahmose: ca. 1550–1525 B.C.

Amenhotep I: ca. 1525–1504 B.C.

Thutmose I: ca. 1504–1492 B.C.

Thutmose II: ca. 1492–1479 B.C.

Thutmose III: ca. 1479–1425 B.C.

Hatshepsut (as regent): ca. 1479–1473 B.C.

Hatshepsut: ca. 1473–1458 B.C.

Amenhotep II: ca. 1427–1400 B.C.

Thutmose IV: ca. 1400–1390 B.C.

Amenhotep III: ca. 1390–1352 B.C.

Amenhotep IV: ca. 1353–1349 B.C.

Akhenaten: ca. 1349–1336 B.C.

Neferneferuaton: ca. 1338–1336 B.C.

Smenkhkare: ca. 1336 B.C.

Tutankhamun: ca. 1336–1327 B.C.

Aya: ca. 1327–1323 B.C.

Haremhab: ca. 1323–1295 B.C.

[Source: Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002]

Dynasty 19, ca. 1295–1186 B.C.

Ramesses I: ca. 1295–1294 B.C.

Seti I: ca. 1294–1279 B.C.

Ramesses II: ca. 1279–1213 B.C.

Merneptah: ca. 1213–1203 B.C.

Amenmesse: ca. 1203–1200 B.C.

Seti II: ca. 1200–1194 B.C.

Siptah: ca. 1194–1188 B.C.

Tawosret: ca. 1188–1186 B.C.

Karnak King List drawing 3

Dynasty 20, ca. 1186–1070 B.C.

Sethnakht: ca. 1186–1184 B.C.

Ramesses III: ca. 1184–1153 B.C.

Ramesses IV: ca. 1153–1147 B.C.

Ramesses V: ca. 1147–1143 B.C.

Ramesses VI: ca. 1143–1136 B.C.

Ramesses VII: ca. 1136–1129 B.C.

Ramesses VIII: ca. 1129–1126 B.C.

Ramesses IX: ca. 1126–1108 B.C.

Ramesses X: ca. 1108–1099 B.C.

Ramesses XI: ca. 1099–1070 B.C.

Hight Priests (HP) of Amun ca. 1080–1070 B.C.

HP Herihor: ca. 1080–1074 B.C.

HP Paiankh: ca. 1074–1070 B.C.

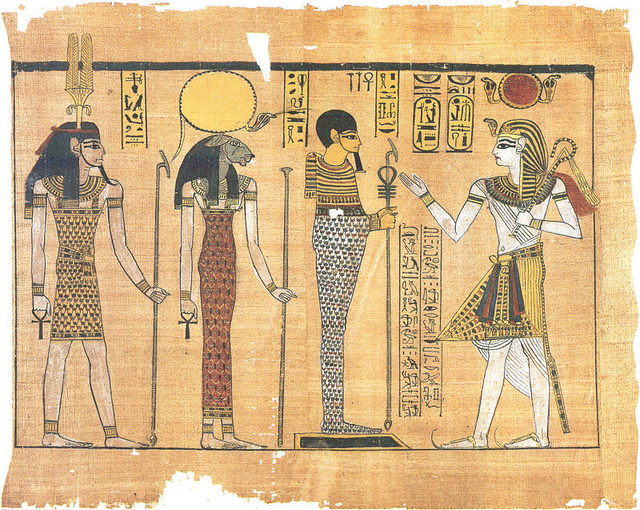

The New Kingdom reached its peak under strong pharaohs that led Egypt into war and helped bring a renaissance in art and architecture that had declined in the second intermediate period.Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: during the 18th Dynasty “a succession of extraordinarily able kings and queens laid the foundations of a strong Egypt and bequeathed a prosperous economy to the kings of the nineteenth dynasty. Thutmose I’s conquered the Near East and Nubia; Queen Hatshepsut and Tuthmose III, who made Egypt into the first super power; the magnificent Amenhotep III, who began an artistic revolution; Akhenaton and Nefertiti, who began a religious revolution by adopting the concept of one god; and finally, Tutankhamen, who has become so famous in our modern age.” [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology Magazine: The 18th Dynasty, one of ancient Egypt’s most storied bloodlines. Among its rulers were conquerors such as Ahmose (r. ca. 1550–1525 B.C.) and Thutmose III (r. ca. 1479–1425 B.C.), military commanders including Horemheb, the controversial king Akhenaten (r. ca. 1349–1336 B.C.), his renowned wife Nefertiti, and Tutankhamun, perhaps Egypt’s most famous ruler. The 18th Dynasty was the first dynasty of the New Kingdom and began when its founder, Ahmose, drove out the Hyksos, foreign kings who originally hailed from the Levant and who had ruled parts of northern Egypt for more than 200 years. Ahmose’s reunification of Egypt ushered in a period of unparalleled prosperity. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt: A Genealogical Sourcebook of the Pharaohs” Amazon.com;

”Private Lives of the Pharaohs: Unlocking the Secrets of Egyptian Royalty” by Joyce Tyldesley (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Pharaohs” by Joyce Tyldesley (2009) Amazon.com;

“Pharaohs: The Rulers of Ancient Egypt for Over 3000 Years” by Dr Phyllis G Jestice (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt” by Elizabeth Payne (1981) Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom" by Joyce Tyldesley (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume III: From the Hyksos to the Late Second Millennium BC” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt: A Captivating Guide” Amazon.com;

“Local Elites and Central Power in Egypt during the New Kingdom”

by Marcella Trapani Amazon.com;

"The New Kingdom" by Wilbur Smith, Novel (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Late New Kingdom in Egypt (c. 1300–664 BC) A Genealogical and Chronological Investigation (Oxbow Classics in Egyptology) by M. L. Bierbrier (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East” by Amanda H Podany (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

Ahmose I (1550–1525 B.C.)

Ahmose (1550-1525 B.C.) is something of a hero in ancient Egyptian history. He founded the 18th dynasty and reunited Egypt after a long period of foreign domination. He defeated the Hyksos and drove them from Egypt, and reunified Egypt and set the stage for expansion into Africa and the Middle East. Ahmose built a number of monuments in Abydos, including the last royal pyramid and a structure with scenes from Ahmose’s battle victories. He is believed to have been the first Pharaoh to be buried in the Valley of the Kings, launching a tradition that would endure for four centuries.

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Ahmose I, (also known as Amosis I) was the first king of the 18th Dynasty and ruled for an estimated 26 years. After becoming Pharaoh he fought in the final battle to expel the Hyksos from Egypt. He then followed the Hyksos to Palestine where he defeated them which marked the beginning of the New Kingdom. Ahmose I led campaigns to solidify the border in Syria in order to keep out a possible invasion from Nubia. Among the many other things he did, Ahmose I may be best known for starting many building projects such as temples. He was buried near Dra Abu el-Naga in the Theben necropolis.” [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Aahotep, the mother of King Ahmose I, was a military leader. She received the “Golden Flies” awarded to soldiers who fought courageously. When Ahmose died, his son Amenhotep became pharaoh. When he failed to produce a son, a military leader named Thutmose I was installed as Pharaoh because he was considered strong and had married a princess.

Amenhotep I (1525–1504 B.C.)

Amenhotep I (1525–1504 B.C.) was the second Pharaoh of Egypt's 18th dynasty. He ruled for over two decades in 1525 B.C. He consolidated Egyptian power following his father’s expulsion of the Hyksos invaders from Lower Egypt. The pharaoh initiated a building program that saw the construction or expansion of numerous temples. Nobody knows how the pharaoh died or where he was originally buried.

Amenhotep I expanded Egypt in northern Sudan. Although his own tomb has not been found, Amenhotep I is believed to have started the tradition of rulers being buried in the Valley of the Kings. He and his mother, Ahmose Nefertari, are also credited with founding the village at Deir el Medina and were worshipped as patron gods there.

Amenhotep I became a god after his death and was the focus of an important cult in Thebes. His followers consulted him on questions of justice. Irene Cordón wrote in National Geographic: Although it was common for especially renowned pharaohs to become the center of cults after their death, Amenhotep’s is among the most popular and enduring. Egyptians believed that his spirit resided in his oracular statue and proper ceremonies could summon it. Residents often turned to the statue to settle legal disputes. [Source: Irene Cordón, National Geographic, January 30, 2019]

Bearing Amenhotep I’s statue on their shoulders, priests would carry it out of the temple during processions and on feast days. A crowd would gather around it, and litigants would present their cases to the statue. Each side would present its case or question, either verbally or in writing. The god’s answers were interpreted by its swaying movements.

Amenhotep I's Mummy

In December 2021, 3D CT scanners 'unwraped' the mummy of Amenhotep I, revealing a seemingly healthy 35-year-old with no indications of how he died. “The images showed "unprecedented detail" of the body of Amenhotep I, said Sahar Saleem, a professor of radiology and lead author of a study on the mummy. “The scans were able to age the Pharaoh and tell that he was 5 feet, 6 inches, tall, circumcised, had a narrow chin, a small narrow nose, curly hair, mildly protruding upper teeth, and a pierced left ear. [Source: Bethany Dawson, Business Insider, January 2, 2022]

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Amenhotep I’s mummy was not found in its original burial location but in the ancient town of Deir el-Bahari, where it was part of a cache of mummies, many of them royal as well. These mummies had been collected during the 21st Dynasty (ca. 1070–945 B.C.) by priests who rewrapped and reinterred them in new coffins. Many of the cache’s mummies had been badly damaged by tomb robbers before being collected. Saleem’s scans show that the priests who rewrapped and reinterred Amenhotep I’s mummy carefully reattached his head with a resin-treated linen band. His neck had been broken, likely when looters tore off a necklace. They also rearranged his broken left arm, covered a hole in his stomach, and placed gold amulets inside. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, January/February 2023]

“The study provides evidence for the great care taken by the priests of the 21st Dynasty in reburying the mummy of Amenhotep I, preserving the golden ornaments, and placing many amulets inside,” Saleem says. “This restores confidence in the goodwill of the priests to rebury the royal mummies to preserve them, contrary to modern allegations that the goal was to steal the ornaments.” She was also able to see that the pharaoh’s right arm had been folded over his chest in its original mummification position. “Folding the arms on the chest became characteristic of royal mummies to make them resemble Osiris, god of the afterlife,” Saleem says. “Amenhotep I’s mummy is the first example of this style of mummification, which later became standard for all ancient Egyptian mummies.”

Thutmose I (1525-1512 B.C.)

Thutmose I mummy When Ahmose died, his son Amenhotep became pharaoh but he left no male heirs. Thutmose I, a commoner and army general, became king by marrying Amenhotep’s sister Nefertiri. Thutmose I was a strong pharaoh, As the skilled commander of a large professional army, he conquered Nubia in the south and advanced as far as the Euphrates River in the north; the farthest any pharaoh had gone up to that time. He erected two large obelisks at Karnak Temple and began the tradition of royal burials in the Valley of the Kings.

Thutmose I was considered a charismatic leader and effective and cruel military campaigner. He once sailed into Thebes with the naked body of a rebellious Nubian chieftain dangling from the prow of his ship. According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “ One of these great pharaohs of the New Kingdom was Thuthmosis I. Thuthmosis I was the third pharaoh in the 18th dynasty (the first dynasty of the New Kingdom). He ruled from 1525-1512 B.C. and proved to be a capable leader and general. He held the borders that he inherited against the Mitanni people, and was not afraid to do so himself. Although Thuthmosis I has a reputation as a military leader, his greatest achievement was the creation of the Valley of the Kings. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“Thutmose I was the Pharaoh who inaugurated the tradition of burial in the Valley of the Kings. He rose to power due to the premature death of Amenophis I's son, Amenemmes, and his was marriage to Amenophis I's sister. Thutmose I extended the Egyptian control to the island of Argo at the third cataract, where he built the fortress of Tombos. He was able to leave an inscription at Argo on what is known as the Tombos Stele, describing an empire that extended from the third cataract to the Euphrates River. He was the father of Thutmose II and Hatshesut. Hatshesut, the only female Pharaoh, dressed in men's clothes and she was always depicted as a man in arts. +\

“The Valley of the Kings was built by Thuthmosis I to battle against the problem of grave robbers. Many less pious Egyptians found out that the pyramids and temples that housed the mummies of the pharaohs contained riches and robbing them proved to be quite lucrative. Thuthmosis I undertook the monumental task of building the valley burial sites on the West Bank of the Nile river by creating a whole village to house the thousands of construction workers. Most of the workers at the Valley of the Kings were literate and their city was named Deir el-Medina. Thuthmosis himself was buried in the Valley of the Kings, but parts of his tomb were robbed. Although despoiled, in his tomb was found a definite version of the book of What is in the Underworld.. The book is a collection of funerary texts that started in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.). +\

“Thuthmosis I may not be remembered as well as Kufu the pyramid builder or Ramesses II the military leader, but he is still no doubt important to ancient Egyptian history. His major contribution comes in the creation of the Valley of the Kings, a network of tombs that would help preserve ancient Egyptian history for modern Egyptologists to discover.” +\

Thutmose II (d. 1503 B.C.)

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Thutmose II was the King of Egypt during the 18th Dynasty. Scholars have differing opinions on the length of his reign, but it is known that he was the fourth Pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty, succeeding his father Thutmose I. His rule was relatively short and has been estimated to have been in charge from 1512 B.C. to 1503 B.C.. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“Thutmose II was married to Hatshepsut, who was his half-sister. Because his father, Thutmose I, had no sons with the royal queen, he had to marry one of her daughters. The practice of marrying within the family was common for the royal families of Egypt. It was done so they would not have to produce children with the blood of a commoner or to legitimize any heirs’ claim to the throne. This was the case with Thutmose II. This interbreeding was not always a good thing, however. Thutmose II was both physically and mentally weak and dominated by his wife and half-sister, Hatshepsut. This was probably a result of the practice of intermarrying. Pharaoh's often had other wives. This was the case with Thutmose II as well. He and a minor wife produced an heir to the throne named Thutmose III. +\

Thutmose II mummy

“Thutmose II preserved his father's (Thutmose I) empire with two campaigns. One of the campaigns crushed a revolt in Nubia in the first year of his reign. The other campaign was directed against the Shosu Bedouin of southern Palestine, which took him to Niy (later called Apamea and and now Qalat el-Mudikh) in the region of Nahrin. Hatshesut, the wife and sister of Thutmose II, is believed to have been the true ruler behind Thutmose II. +\

“Thutmose II is not known to have accomplished much during his reign. He is believed to have battled against the nomadic Bedouins and Nubians who rebelled against his rule. He also built a small funerary temple in western Thebes. Archaeologists have not been able to find or positively identify a tomb belonging to him, but his mummy was found reburied in the royal cache at Dayru I-Bahri in 1881. +\

“When he died, his son Thutmose III was too young to rule the throne and Hatshepsut took over as Regent until he was old enough. She even went so far as to dress in a false beard to legitimize her rule. Once Thutmose III was old enough to rule, she subdued him and tried to send him away. This was done so she could find a way to get her daughter Nefrure put in place as “King.” Both Hatshepsut and Nefrure died and it is not known how, but Thutmose III is believed to have been involved in their deaths. Thutmose III took over and ended Hatshepsut’s peaceful rule and mobilized the military. +\

Karnak Temple Under Thutmose I and II

Elaine Sullivan of UCLA wrote: ““The construction efforts of Thutmose I had a great impact on the arrangement of the temple for years to come. Scholars have generally attributed both the fourth and fifth pylons to the king, as well as a corresponding stone enclosure wall, which together still form the core area of the temple. Thutmose I originally lined the court of the fifth pylon with a portico of 16 fasciculated columns. By erecting the first pair of granite obelisks at Karnak in front of the fourth pylon (the temple’s main gate at the time), Thutmose began an association of obelisks with the god Amun-Ra that may have bolstered the divinity’s rising universality. His act was emulated and outperformed (with taller and larger obelisks) by a number of 18th and 19th Dynasty rulers. [Source: Elaine Sullivan, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Politically, Karnak took on new importance in the 18th Dynasty, as the pharaohs began to use the temple as a means of demonstrating their divinely ordained selection as king. The enhancements of Thutmose I highlight this change: among his contributions to the temple was the addition of a wadjet hall, where coronation rituals took place with the god Amun-Ra sanctioning the choice. The wadjet hall was originally an open-air court between the new fourth and fifth pylons of the king.

“Thutmose II added a new pylon to the west of the old temple entrance (later torn down for the construction of the third pylon, so it does not figure in the pylon numbering system at Karnak), creating a large “festival court,” enclosing the obelisks of Thutmose I within the building, and establishing a new western gate to Karnak. Along the hall’s south side, a small pylon entrance led to the constructions along the temple’s southern axis. Gabolde has used blocks found in the third pylon to reconstruct the appearance of the inscribed doors, side walls, and small pylon of the court.

“Thutmose II commissioned a pair of red granite obelisks, inscribed fragments of which have been found at Karnak, presumably for placement in his new hall. Gabolde has reconstructed (on paper) one of these monoliths. The preserved inscriptions of the king show that the monument originally belonged to him, but that he must have died before it could be completed and raised, as Hatshepsut added her own inscription, with a dedication to her father, Thutmose I. Two socles found subsumed by the third pylon and its gate likely mark the location of these obelisks .

Thutmose I, copy of a relief at Deir el Bahar

“Tura limestone blocks probably recovered from the “cachette court” provide evidence that Thutmose II had constructed a two- roomed bark-shrine for the temple, similar in form to the later “Red Chapel” of Hatshepsut. The bark shrine may have stood in the future location of the Red Chapel, in front of the Senusret I temple, or it may have been positioned in the new “festival court” of the king. The chronology of its destruction is not defined, but modified inscriptions show it must have been dismantled between the ascension of Hatshepsut to the kingship and her proscription at the end of the reign of Thutmose III.

“A painted scene from the Theban tomb of Neferhotep (TT 49) implies that at some time in the 18th Dynasty, a giant T-shaped basin connected to the Nile by a canal was cut on the west side of the temple. A rectangular quay is depicted as flanking its eastern edge. If the basin was located in the vicinity of the later second pylon, as Michel Gitton suggested in his reconstruction of Karnak in the reign of Hatshepsut, the Nile must have shifted westward from its location in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.). It is perhaps this shift that allowed the westward expansion of the temple in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.). The presence of a canal and basin may equally have limited further movement of the temple west at this time.”

Thutmose III (1480-1426 B.C.)

Thutmose III is regarded was as the Napoleon of Egypt. Only 5 foot 3, he mounted at least 14 military campaigns, some of which he personally led, and won them all if historical records are to be believed . He helped the Egyptian empire reach the height of its power and size. His military campaigns expanded the borders of Egypt into Syria, Palestine and Nubia. During the last ten years of his reign Egypt was peaceful and prosperous.

Thutmose III assumed power after his stepmother Queen Hatshepsut died in 1458. He ruthlessly defaced her images and raised many monuments of himself. Otherwise he was regarded as a compassionate warrior who did not enslave enemy soldiers nor massacre civilians. He kept foreign princes obedient by holding their sons hostage in gilded cages and introduced chicken to ancient Egypt.

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Thutmose III was admired and revered for generations to come for having a great impact on Egypt both as a nation and as a culture. He constructed many great buildings and obelisks throughout his empire. Buildings were constructed at Heliopolis, Memphis, Abydos, and Aswan, as well as the additions made to the great temple at Karnak, where he had his annals inscribed in the walls. During the last year of his life he appointed his son Amenhotep II to succeed him. Amenhotep II was the son of Thutmose III’s second wife Meryetre, who was Hatshepsut’s daughter and Thutmose III’s half sister. Thutmose III was laid to rest, in 1426 B.C. in the Valley of the Kings in western Thebes. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

See Separate Article: THUTMOSE III (1480-1426 B.C.): ANCIENT EGYPT’S GREATEST RULER? africame.factsanddetails.com

Queen Hatshephut (1479 to 1458 B.C.):

Couple and child, made in the reign of Thutmose IV

Queen Hatshepsut was the only female to rule Egypt as a full pharaoh in a period when Egypt was strong. Often depicted as a man with a false beard, she rose to power after claiming divine birth. Her name means “the first, repeatable lady.” Other women ruled but they did so in weak period. Twosret was another female ruler. She ruled from 1198 B.C. to 1190 B.C. One, possibly two, other female pharaohs ruled briefly. Cleopatra came along 14 centuries after Hatshepsut. She wasn’t a Pharaoh or even full-blooded Egyptian but rather a Greek that ruled over the remains of a kingdom established by Alexander the Great. [Source: Chip Brown, National Geographic. April 2009; Elizabeth Wilson, Smithsonian magazine, September 2006; Peter Schjeldahl, The New Yorker]

Hatshepsut was the Queen of Egypt during the 18th Dynasty. The daughter of Thutmose I, she married Thutmose II. When he ascended to the throne she became the real ruler. When he died she acted as regent for his son, Thutmose III, then had herself crowned as Pharaoh. Maintaining the fiction that she was a male, she was represented with the regular pharaonic attributes, including a beard.[Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Queen Hatshepsut ruled from 1479 to 1458 B.C. She was referred to by both male and female pronouns depending on the situation but was regarded politically as an “honorary man.” There was no Egyptian word for "Her Majesty." People addressed her as "His Majesty." Bas-reliefs and statues often depict her with a lion’s mane and a male headdress in addition to the false beard.

See Separate Article: HATSHEPSUT (1479 TO 1458 B.C.): HER FAMILY, LIFE AND REIGN africame.factsanddetails.com

Thutmose IV (1426-1415 B.C.)

According to to one story, about 1400 B.C., when Thutmose IV was a prince he fell asleep under the Sphinx's chin and had a dream that someday he would free the statue from the sand. When he became Pharaoh he covered the Sphinx with limestone blocks, added the masonry forelegs and painted it yellow, blue and red. He placed a statue of his father — and a red granite stela with the story of his dream — on the Sphinx's chest. In the time of Thutmose IV the Sphinx was as ancient as Chatres cathedral is to us today. Ramses the Great later reworked the statue, added two more stelae and scratched in his name (and probably erased the name of Thumose's father). Thutmose IV expelled Mesopotamian invaders known as Mitanni. He may have killed his brother to claim the throne.

Joel R. Siebring of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: “The father of Thutmose IV was Amenhotep II and his mother was Queen Tio. His wife was the daughter of the Mitannian King, Artatama. She was given the Egyptian name of Mutemuya and became the mother of Amenhotep III, the next king of Egypt. It is believe that Thutmose IV was not the first in line for the throne. He had an older brother that met an early end before he got to the throne. This is based upon a written story found about a dream that Thutmose IV had of the great sphinx of Giza telling him how one day he would be king. [Source: Joel R. Siebring ,Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“As a young prince, Thutmose IV served in the northern army corps at Memphis. Thutmose IV lead a army unit known as ‘Menkheprure, Destroyer of Syria’, and as pharaoh at this time period holds the position of Commander-in –Chief of the Army. Thutmose IV also fought a war in Nubia from which Egypt received a great deal of wealth. He made treaties with neighboring countries such as Babylonia that ushered in an era of peace and political stability lasting through the reign of his son Amenhotep III. +\

“Thutmose IV is known for being the first king in battle on a chariot against foreign enemies. He followed in his father's footsteps by freeing the Sphinx from its sand tomb. He held his grandfather, Thutmose III, in respect and completed the obelisk planned by him. Thutmose IV was found in a small additional room between the sepulchral hall and the antechamber in the Valley of the Kings.” +\

An inscription on "A Syrian Captive Colony" under Thothmosis IV from the 14th century B.C. reads: “The settlement of the fortification of Men-khepru-Re (Thothmosis IV) with the Syrians (=Kharu) [of] his majesty's capturing in the town of Gez[er].” [Source: James B. Pritchard, “Ancient Near Eastern Texts,” Princeton, 1969, ANET., pp. 248. web.archive.org]

Amenhotep III (1390–1352 B.C.)

Amenhotep III Colossal Amenhotep III(1390-1353 B.C. ) ruled for 38 years during a period of relative peace and prosperity . He built the Colossi of Memnon and the Mortuary of Amenhotep III and spent a lot of time hunting. One commemorative scarab said he killed “102 fearful lions” during the first 11 years of his rule. [Source: Andrew Lawler, Smithsonian magazine, November 2007]

Amenhotep III controlled a rich empire stretching 1,200 miles from the Euphrates in the north to the Fourth Cataract of the Nile in the south. Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic, “Along with his powerful queen Tiye, he worshipped the gods of his ancestors, above all Amun, while his people prosper and vast wealth flows into the royal coffers from Egypt's foreign holdings.”[Source: Zahi Hawass, National Geographic, September 2010]

Dr Kate Spence of Cambridge University wrote for the BBC: The reign of Amenhotep III was “long and prosperous with international diplomacy largely replacing the relentless military campaigning of his predecessors. The reign culminated in a series of magnificent jubilee pageants celebrated in Thebes (modern Luxor), the religious capital of Egypt at the time and home to the state god Amun-Re.” [Source: Dr Kate Spence, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Amenhotep III came to the throne as a teenager after the death of his warrior father Thutmose IV. He chose to spend much of his time in Thebes (Luxor) rather than Memphis, where most of the other pharaohs spent their time . After quelling an uprising in Nubia he chopped off the arms of 312 enemies but was more restrained and diplomatic during most of his rule. His principal wife Tiye by various accounts was a Nubian, a commoner or from a noble Egyptian family. His harem included women from rival powers such as Babylon and Mitanni. Queen Tiye (1390-1349) was deeply involved in politics. She abdicated when the king died and made a living as a goddess.

See Separate Article: AMENHOTEP III (1390–1352 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

Akhenaten (1353 B.C. to 1336 B.C.)

Akhenaten was one of ancient Egypt’s the most influential and divisive pharaohs and one world's most important religious innovators. Considered the father of monotheism, he established a monotheistic cult to Aten (“Sun Disk”) and forced Egyptians to abandon the worship of all other gods. He once boasted "My Lord promoted me so that I might enact His teaching." [Source: Rick Gore, National Geographic, April 2001]

Akhenaten was originally known as Amenhotep IV. Later he changed his name from Amenhotep ("Amun, the Sun God, is content") to Akhenaten ("Light in the Sun Disk"). His father was Amenhotep III. DNA analysis in February 2010 determined that Akhenaten was the son of Amenhotep III and father of Tutankhamun (King Tut). It identified Queen Tiye as the mother of both Akhenaten and his sister-wife (See Amenhotep III).

The statues of Akhenaten are much different than the statues of other pharaohs. He has a long thin face with Asian-style eyes, a prominent nose and full, protruding lips and an oval-shaped head. He is sometimes depicted with a sensuous belly and broad feminine hips. Other times he has a small pot belly and a shallow chest. Some scholars believe his misshapen skull and strange facial features may have been the result a tumor in his pituitary gland. Others have suggest his unusual facial and body features may have been efforts to express the bisexual nature of his single god.

Akhenaten is arguably the second best known pharaoh after his Tutankhamun (King Tut). His image in the Egyptian Museum is among the most memorable there. Agatha Christie wrote a play about him; Phillip Glass penned an opera about him and Nobel-prize-winning Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz wrote a novel “Dweller of Truth” inspired by him. Even Sigmund Freud wrote at length about him and his beliefs, arguing that Moses was an Egyptian priest spreading the word of Aten.

See Separate Article: AKHENATEN (1353 B.C. TO 1336 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

King Tutankhamun (ruled 1334 to 1325 B.C.)

King Tutankhamun, better known as King Tut, became a pharaoh at age 9 and died when he was 19. Little is known of his life. Nothing in particular distinguished his career, and he probably would not be remembered were it not for the discovery of his unlooted tomb in 1922, which caused a big brouhaha even though relative to other Pharaohs it was not even a particularly grand tomb. Tutankhamun’s name was not even included on the classic “King’s List” at the temples of Abydos and Karnak. Despite all this King Tut is the Pharaoh the public knows best. [Source: Richard Covington, Smithsonian magazine, June 2005]

Tutankhamum is believed to be the son of Akhenaten. Nefertiti, Akhenaten’s first wife, was his stepmother. Tutankhamun’s his reign lasted for 16 years. Sometime during his reign he married Ankhesenpaaten. Apart from the return to Thebes and the cult of Amun, few events of his reign were documented. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

King Tutankhamun was the last heir of a powerful family that ruled ancient Egypt for many centuries. Although his rule was unfilled his death was treated with great fanfare as he was the last of his line. It is astonishing how Tutankhamun continues do fascinate people today. More than 8 million people showed up to see his mask and artifacts from his tomb during the King Tut tour of the United States in the 1977. The comedian Steve Martin gave his career a big boost when he recorded a silly song about the pharaoh around the time of the tour. An exhibit in the mid 2000s called “Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs” — similar to one in 1977 — cleared $10 million in each city it appeared in. The admission fee was as high as $30 — a lot at that tome. More than a million people saw the exhibit in Chicago and Philadelphia and nearly a million saw it in Los Angeles. The tour took place in spite of a ban that had been imposed after a gilt statue from Tut’s tomb was broken during a tour of Germany in 1982.

See Separate Article: KING TUTANKHAMUN (KING TUT, 1334 TO 1325 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

Seti I

Seti I (1294–1279 B.C.) was the son of Ramses I and the father of Ramses II. Seti I’s reign looked for its model to the mid-18th dynasty and was a time of considerable prosperity. He restored countless monuments. His temple at Abydos exhibits some of the finest carved wall reliefs. He is known most for his military exploits in Palestine.John Ray of Cambridge University wrote for the BBC: Seti I’s “reign saw military success as well as achieving one of the high points of Egyptian art, marked by sensitivity, balance and restraint. [Source: John Ray, Cambridge University, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Seti I (1306-1290 B.C.) ruled for 11 years during which he expanded Egypt’s influence south to Nubia and northeast to Syria.

Seti I was a "vigorous warrior." He expanded the Egyptian empire to include Cyprus and parts of Mesopotamia. Seti I lives on as one of the best-preserved mummies. His face is on display at the Egyptians Museum. The Egyptologist Methew Addams told the New York Times, “people have been influenced by that face in their interpretation of Seti as having been a good, wise king, We are really projecting our own esthetic on him.” [Source: John Ray, Cambridge University, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Seti I took his son Ramses II on military campaigns to Libya when he was 14 and later to Syria to battle the Hittites. Seti I's reign saw military success as well as achieving one of the high points of Egyptian art, marked by sensitivity, balance and restraint. These were the hard acts which it was Ramesses' destiny to follow, and one way of doing this would be to upstage the past by ostentation, thereby eclipsing it. Ramesses II was well suited to this kind of role, and the gods gave him a reign of 67 years in which to perfect his act.

See Separate Article: SETI I (1294–1279 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

Ramses II (ruled 1279 to 1213 B.C.)

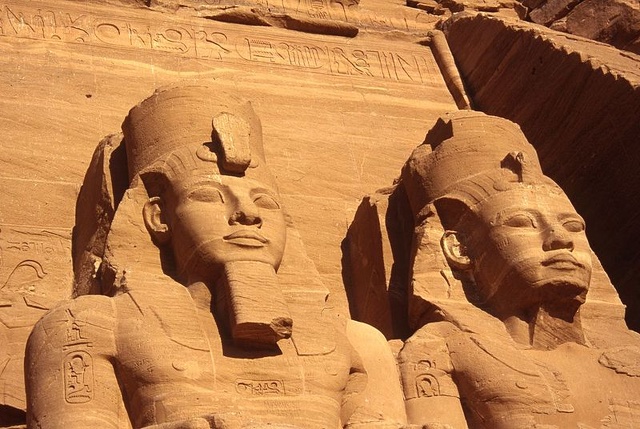

Ramses the Great, also known as Ramses II, was perhaps the greatest of all the Egyptian pharaohs. He became Pharaoh in 1279 B.C. when he was in his twenties and the pyramids were already 1,300 years old. He ruled ancient Egypt for 67 years during the golden age of the civilization. He raised more temples, obelisks and colossal monuments that any other Pharaoh and ruled an empire that stretched from present-day Libya and Sudan to Iraq and Turkey. The Bible refers to him simply as "Pharaoh." [Source: Rick Gore, National Geographic, April 1991]

Ramses, which means "Son of Ra," was five feet eight inches — tall by ancient Egyptian standards. "He had a strong jaw; a beaked nose, a long thin face," says James Harris of the University of Michigan, who X-rayed the Pharaoh's mummy, "That was not typical of earlier pharaohs. He probably looked more like the people of the eastern Mediterranean. Which is not surprising, because he came from the Nile delta, which had been invaded in the past by peoples from the east."

The mummy of Ramses the Great has Great has a shock of soft reddish-blonde hair with the texture of peach fuzz. CT scans and studies of tissue material from Ramses II’s body in the 2000s indicate that the Pharaoh had blackheads, arthritis and hardening of the arteries. X-rays of the mummy done in the 20th show he had arthritis of the hip, which forced him to stoop, and gum disease.

Ramses died at the age of 92 or 96. Having outlived many of his older sons, his 13th son ascended to the throne upon his death in 1298 B.C. Within 150 years after he was buried Ramses tomb was looted and the mummy was desecrated. In 1150 B.C., a grave robber confessed under torture to plundering the tombs of Ramses and his sons. Today Ramses unwrapped red-haired body lies today in the Cairo Museum.

See Separate Article: RAMSES THE GREAT (RULED 1279 TO 1213 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

Setnakht (1186-1184 B.C.): First King of the 20th Dynasty

Sethnakhte established the 20th Dynasty and was the father of Ramses III. Pierre Grandet wrote: The “Seth” element in his name, as well as the very fabric of his titulature, seem to imply that he was, like the 19 th-Dynasty founders, an army general from the eastern Delta. It is possible that he was a native of Bubastis (modern Zagazig) or had served in this city for the largest part of his career, as evidenced by the existence, under Ramesses III, of an unusually important group of Bubastite dignitaries. [Source: Pierre Grandet, 2014, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“True to Egyptian tradition, our sources present the king’s election to the throne as a personal choice by the gods—in this case, by the god Seth—formalized by an oracular ceremony in Seth’s temple at Avaris, if we so interpret the allusion in Sethnakhte’s Elephantine Stela, l. 4-5 . Behind this fiction, the true nature and means of his accession to power are unknown (rule of seniority?; election among peers?; forceful seizure?).

“As he was probably already an elderly man, the king commissioned his son, the future Ramesses III, to act in hi s stead, both in civil and military matters. Se thnakhte retained the incumbents of the major administrative offices (Hori as Northern Vizier and Hori, son of Kama, as Viceroy of Kush) but promoted a middle-ranking officer of the Theban Amun’s Domain, Bakenkhonsu, to be First Prophet of Amun. Despite the brevity of Sethnakhte’s reign, archaeological and textual records attest to some achievements, modest in scope but encompassing the whole of Egypt. He is even mentioned outside its borders, in Serabit el-Khadim and Amara-West.

“Due to technical problems, Sethnakhte’s tomb (KV 11) was still unfinished when he died and he was buried in the innermost funerary chamber of queen Tauseret’s tomb (KV 14). No funerary temple of his has ever been found on the Theban West Bank, but his posthumous cult has left some textual traces, both in Thebes and in Abydos, where Ramesses III would consecrate a small chapel to his parent’s memory.”

Ramses III (1195 – 1164 B.C.)

Ramses III, the 2nd king of the 20th Dynasty, ruled for about 31 years during the New Kingdom. His reign is marked by a long list of achievements, including an impressive building program, military successes, and a number of expeditions. He was the leader of Egypt at a time when the rest of the Mediterranean World was in turmoil. The fall of Mycenae and the Trojan War displaced many people and forced them to relocate elsewhere, unsettling the entire region. The long period of stability in the Middle East initiated by Thutmose III’s conquest and creation of a strong Egyptian state and solidified by Ramses II’s treaties with the Hittites was unraveling Failed harvests and famine didn’t help matters.. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Ramses III is best known for defeating the Sea Peoples — a combination of several different peoples that some historian gave birth to the Phoenicians. The "Sea People," ravaged the Near East and advanced south towards Egypt and were halted by Ramses III in the fifth year of his reign. Among his other accomplishments were revived trade with the Land of Punt, reestablishing law and order throughout the country and launching a tree planting campaign. His monuments include the temple at Medinet Habu. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

Ramses III is also known for being at the center of a harem conspiracy that may have killed him. Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “Ramses III had two principle wives plus a number of minor wives and it was one of these minor wives, Tiye, who was the cause of his destruction. She hatched a plot to kill him with the aim of placing her son, Prince Pentaweret, on the throne. She and her confederates stirred up a rebellion and used magic wax images and poison as their weapons. The conspiracy failed and the traitors were arrested but not before Ramses was mortally wounded.” He was buried in the Valley of the Kings. His mortuary temple was unique in that the entrance was a copy of a Syrian migdol. ^^^

See Separate Article: RAMSES III (1195 – 1164 B.C.): THE LAST GREAT PHARAOH africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024