Home | Category: New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut)

AKHENATEN

Akhenaten Akhenaten was one of ancient Egypt’s the most influential and divisive pharaohs and one world's most important religious innovators. Considered the father of monotheism, he established a monotheistic cult to Aten (“Sun Disk”) and forced Egyptians to abandon the worship of all other gods. He once boasted "My Lord promoted me so that I might enact His teaching." [Source: Rick Gore, National Geographic, April 2001]

Akhenaten was originally known as Amenhotep IV. Later he changed his name from Amenhotep ("Amun, the Sun God, is content") to Akhenaten ("Light in the Sun Disk"). His father was Amenhotep III. DNA analysis in February 2010 determined that Akhenaten was the son of Amenhotep III and father of Tutankhamun (King Tut). It identified Queen Tiye as the mother of both Akhenaten and his sister-wife (See Amenhotep III).

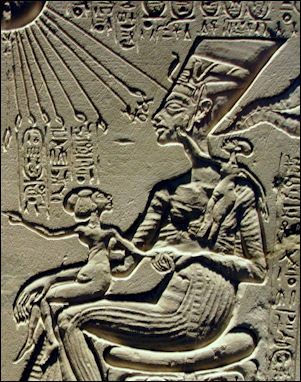

The statues of Akhenaten are much different than the statues of other pharaohs. He has a long thin face with Asian-style eyes, a prominent nose and full, protruding lips and an oval-shaped head. He is sometimes depicted with a sensuous belly and broad feminine hips. Other times he has a small pot belly and a shallow chest. Some scholars believe his misshapen skull and strange facial features may have been the result a tumor in his pituitary gland. Others have suggest his unusual facial and body features may have been efforts to express the bisexual nature of his single god.

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “Akhenaten was an intellectual and philosophical revolutionary who had the power and wealth to indulge his ideas. However, the ancient Egyptians were a deeply religious people who loved their ancient traditions and were not ready to embrace such radical changes. It would not be until the Christian era that the Egyptians would finally reject the old gods in favour of a single universal deity. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

RELATED ARTICLES:

AKHENATEN AND MONOTHEISM africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AKHENATEN AND AMARNA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NEFERTITI: HER LIFE, BEAUTY, BUST AND MARRIAGE TO AKHENATEN africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AKHENATEN'S REIGN (1353 B.C. TO 1336 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Akhenaten: A Historian's View” by Ronald T. Ridley, Aidan Dodson, Salima Ikram Amazon.com;

“Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen” by Rita E. Freed and Yvonne J. Markowitz (1999) Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten: King of Egypt” by Cyril Aldred Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt” by Dominic Montserrat (2000) Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten: The Heretic King” by Donald B. Redford (1984) Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten and the Religion of Light” by Erik Hornung and David Lorton (2001) Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten and the Origins of Monotheism” by James K. Hoffmeier Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten: Egypt's False Prophet” by Nicholas Reeves and C. N. Reeves Amazon.com;

“Son of God, Son of the Sun: The Life and Philosophy of Akhenaten, King of Egypt”

by Savitri Devi, David Skrbina (2023) Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Golden Couple: When Akhenaten and Nefertiti Were Gods on Earth”

by John Darnell and Colleen Darnell Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten, Dweller in Truth” by Naguib Mahfouz (1985), Novel by Nobel Prize winner Amazon.com;

“Amarna: A Guide to the Ancient City of Akhetaten” by Anna Stevens (2021) Amazon.com;

“The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and Its People” by Barry Kemp Amazon.com;

“The Twelfth Transforming” by Pauline Gedge (1984) Novel Amazon.com;

“The Year of the Cobra (Akhenaten Trilogy, Book 3) by Paul C. Doherty. Novel (2006) Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom" by Joyce Tyldesley (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume III: From the Hyksos to the Late Second Millennium BC” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt: A Captivating Guide” Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

Ancient Egypt in the Time of Akhenaten

Akhenaten A study by team of researchers lead by Gerome Rose and Barry Kemp of the University of Arkansas of people buried in the cemetery of Tell el-Amarna — a city that was the capital of ancient Egypt for 15 years in the 14th century B.C. under the Pharaoh Akhenaten — found that life was short, brutish and tough for the ancient Egyptians. Many suffered from anemia, fractured bones, stunted growth and high juvenile mortality rates. The study found that anemia ran at 74 percent among children and teenagers buried there and 44 percent among adults. Several teenagers had severe spinal injures, thought to have been caused by construction accidents that occurred during the building of the city. The average height was 159 centimeters among men and 153 centimeters among women. Rose said, “Short stature reflect a diet deficient in protein...People are not growing to their full potential.” [Source: Alaa Shahine Reuters, March 29, 2008]

Rose, a professor of anthropology at the University of Arkansas, told Reuters adults buried in the cemetery were probably brought there from other parts of Egypt."This means that we have a period of deprivation in Egypt prior to the Amarna phase," he said. "So maybe things were not so good for the average Egyptian and maybe Akhenaten said we have to change to make things better," he said.

Rose displayed pictures showing spinal injuries among teenagers, probably because of accidents during construction work to build the city. The study showed that anemia ran at 74 percent among children and teenagers, and at 44 percent among adults, Rose said. The average height of men was 159 cm (5 feet 2 inches) and 153 cm among women. "Adult heights are used as a proxy for overall standard of living," he said. "Short statures reflect a diet deficient in protein. ... People were not growing to their full potential."

On the appeal of Akhenaten and the Amarna period, Dr Kate Spence of Cambridge University wrote for the BBC: “Some people are drawn by interest in Akhenaten himself or his religion, others by a fascination with the unusual art which appeals strongly to the tastes of modern viewers and provides a sense of immediacy rarely felt with traditional Egyptian representation. The radical changes Akhenaten made have led to his characterisation as the 'first individual in human history' and this in turn has led to endless speculation about his background and motivation; he is cast as hero or villain according to the viewpoint of the commentator. [Source: Dr Kate Spence, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Akhenaten’s Life

Jacquelyn Williamson of George Mason University wrote: “Akhenaten was born Amenhotep, named after his father, Amenhotep III. Other than a jar sealing from the Malqata palace of Amenhotep III that mentions him, we have little evidence for Prince Amenhotep’s early years. His older brother Thutmose may have been heir apparent, but Thutmose predeceased their father, making Amenhotep the crown prince. Note however that there are some questions about the authenticity of Thutmose’s so-called “cat’s-coffin,” which preserves the key title “king’s eldest son”. [Source: Jacquelyn Williamson, George Mason University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

Dr Kate Spence of Cambridge University wrote for the BBC: “Akhenaten came to the throne of Egypt around 1353 B.C. The reign of his father, Amenhotep III, had been long and prosperous with international diplomacy largely replacing the relentless military campaigning of his predecessors. The reign culminated in a series of magnificent jubilee pageants celebrated in Thebes (modern Luxor), the religious capital of Egypt at the time and home to the state god Amun-Re. The new king was crowned as Amenhotep IV (meaning 'Amun is content') and temple construction and decoration projects began immediately in the name of the new king. The earliest work of his reign is stylistically similar to the art of his predecessors, but within a year or two he was building temples to the Aten or divinised sun-disk at Karnak in a very different artistic style and had changed his name to Akhenaten in honour of this god. [Source: Dr Kate Spence, BBC, February 17, 2011. Dr Spence is a McDonald Post-doctoral Research Fellow in Cognitive Archaeology in the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge University. She has excavated at Amarna as part of the Egypt Exploration Society Expedition to Amarna directed by Barry Kemp]

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: A newly studied relief from a monument at Karnak dating to around 1350 B.C. — just before Akhenaten turned the Egyptian world upside down — provides fascinating insight into the mind of the pharaoh. The sandstone talatat, Akhenaten’s standardized building block, depicts the pharaoh and Nefertiti, assisted by male servants, preparing for their day. They are shown applying makeup, having their nails cut, purifying themselves, and dressing. “It looks like a very intimate household scene,” says David, but she believes that it actually shows them appropriating a well-known daily ritual described in later papyrus documents that was performed for the cult statue in the most sacred chamber of the temple of the creator god Amun-Ra at Karnak. Through the imagery on the relief, explains David, the pharaoh proclaims himself the divine personification of his personal god, Aten. “Akhenaten didn’t build everything from scratch,” she says. “His decision to throw away the Theban gods was extreme and shocking, but he used already-existing rituals, images, and texts, and recycled them to adapt to his new vision of kingship in which he was the center of everything and alone under his god.” [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

Akhenaten and Nefertiti

Nefertiti and Akhenaten Akhenaten was married to Queen Nefertiti, one of the most famous of all ancient Egyptian women. One inscription shows Akhenaten and Nefertiti with their three daughters. All three daughters have misshapen skulls. King Tut may have been the son of Akhenaten and a secondary queen.

Nefertiti was regarded as a great beauty. A beautiful bust of her is the most prized possession of the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. If she did indeed look like the bust she has neck like a swan and a dedicate face made up in a style that is not different from the way modern women make up themselves. Her name means “beautiful one to come.” Not all renderings of Nefertiti depict her as a glamorous beauty. In some images she looks haggard and tired, During Nefertiti’s reign ordinary people started wearing wigs. Nefertiti herself favored Nubian style wigs and is thought to have shaved here head so her wigs fit more snugly.

Nefertiti parents are unknown although her father may been a vizier for King Tutankhamun. Akhenaten elevated Nefertiti to divine status. She may have been only 12 when she married Akhenaten. During the 12th year of Akhenaten’s reign Nefertiti disappeared from the historical record. Akhenaten's other wife Kiya was referred to as his "Great Beloved."

Nefertiti was one of the most influential queens. Reliefs show here conducting religious ceremonies with Akhenaten as an equal. She had more power perhaps than any other queen. Many scholars believe that Nefertiti may have ruled Egypt as Akhenaten co-regent and after Akhenaten's death may have ruled outright under the name of Ankhkheprure. A hymn to the god Amen with a prayer for the queen, written in around 1300 B.C., goes: "Prize from the Chief Wife of the King, his beloved...Nefertiti, living, healthy, and youthful forever and ever."

Akhenaten's Rule

Akhenatan’s reign can be divided into two phases: the years before the move to the site of Amarna, when building was centered on Karnak in Thebes (Luxor) and the Amarna years. The former is termed the proto-Amarna phase by scholars.

Jacquelyn Williamson of George Mason University wrote: “Amenhotep was approximately ten years old when he assumed the throne. Many once suggested he served the first years of his young rule in a coregency with Amenhotep III, but current opinion holds that their reigns did not overlap. The first two years of Amenhotep IV’s reign conformed to Egyptian royal traditions. He completed his father’s unfinished building projects at Soleb in Nubia as well as the third pylon at Karnak, decorating each in traditional Pharaonic style. Akhenaten may have even started building himself a traditional mortuary temple on the site that is now the Ramesseum. [Source: Jacquelyn Williamson, George Mason University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

Akhenaten ruled for 17 years (from the death of his father Amenhotep III in 1353 B.C. to Akhenaten's death in 1336 B.C.). His reign began with great optimism and hope as expressed by the great works of art that were created in that period.

After an unknown event, five years into his reign, Akhenaten moved the capital of Egypt from Thebes to a new location called Akhetatem ("Horizon of the New Sun") in present-day el-Amarna (180 miles north of Thebes on the east bank of the Nile).

Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic, “In the fifth year of his reign, he changes his name to Akhenaten — "he who is beneficial to the Aten." He elevates himself to the status of a living god and abandons the traditional religious capital at Thebes, building a great ceremonial city 180 miles to the north, at a place now called Amarna. Here he lives with his great wife, the beautiful Nefertiti, and together they serve as the high priests of the Aten, assisted in their duties by their six cherished daughters. All power and wealth is stripped from the Amun priesthood, and the Aten reigns supreme. The art of this period is also infused with a revolutionary new naturalism; the pharaoh has himself depicted not with an idealized face and youthful, muscular body as were pharaohs before him, but as strangely effeminate, with a potbelly and a thick-lipped, elongated face. [Source: Zahi Hawass, National Geographic, September 2010]

Some scholars believe that a natural disaster provoked the move to Amarna. Some have suggested that Akhenaten founded the new capital to escape the bubonic plague ravaging Egypt’s main urban centers. Others believe that priests in Thebes had enough of him and forced him to leave. Within a year or two, a city with 20,000 people had sprouted up on the Nile.

Disappearance and Death of Akhenaten’s Family

Nefertiti and Meketaten In Year 13 and 14 of Akenaten’s rule three his six daughters, the two youngest, Neferneferure and Setepenre, and the second eldest Meketaten, died suddenly. Engravings in a royal tomb show the royal family grieving, either weeping before the princesses' (non-mummified) corpses or paying homage to them via their statues. Around Year 16 Akhenaten's second wife, Kiya disappears from documents. It is believed she might have died around that time. [Source: Dr. Marc Gabolde, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Jacquelyn Williamson of George Mason University wrote: “Between Akhenaten’s regnal years 13 and 17 several members of the Amarna royal family disappear from the archaeological record. At the same time the people of Hatti were suffering from a fatal illness that they believed was brought to them by their Egyptian prisoners of war. If it is true that there was a fatal epidemic disease in Egypt, it may be the cause of the disappearance of these members of the royal family. [Source: Jacquelyn Williamson, George Mason University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

“For example, Akhenaten had a second wife, Kiya. Although she was called “the Greatly Beloved Wife,” around Akhenaten’s year 16 her name and image were removed from several monuments at Amarna, including the Maru Aten, and replaced with the names of Akhenaten’s daughters Meritaten and Ankhsenpaaten. On “talatat “Ny Carlsburg Glyptotek Copenhagen AEIN 1776, Kiya’s name is replaced with Meritaten’s. Although some have suggested she suffered a fall from Akhenaten’s grace, she may have been a victim of the epidemic instead. Her tomb may have been located in the royal necropolis at Tell el-Amarna. In years 13 or 14, three of Akhenaten’s six daughters—Meketaten, Neferuneferura, and Setepenra—disappeared from the record as well.

“However there is a debate surrounding Meketaten’s death in particular, due to the enigmatic nature of a scene in the burial annex assigned to her in the Royal Tomb. The scene shows the royal family mourning Meketaten’s death, accompanied by a nurse holding an infant. This has lead many to suggest the princess died in childbirth. Gabolde’s reconstruction of the scene’s inscriptions indicates that the infant is described as Nefertiti’s child, not Meketaten’s. If so, this may be one of the few representations of the future king Tutankhamen, born Tutankhaten. Still others believe the infant may instead represent Meketaten reborn.

Akhenaten's Mummy and KV 55

In year 14 of Akhenaten’s reign, his mother Queen Tiy died and was buried in the royal necropolis at Amarna. Akhenaten died in year 17 of his reign and was also buried at Amarna, although evidence from KV 55 (Valley of the Kings tomb 55) suggests his mummy was later moved to Thebes.

Akhenaten’s remains were found in 1907 in Egypt's Valley of the Kings in tomb KV 55, just a few meters (feet) from the tomb of Tutankhamen. More than a century after the tomb's discovery, genetic analysis confirmed that the skeleton inside belonged to Akhenaten and was King Tut's biological father. Other clues in the tomb also suggested to archeologists that the man inside KV55 was Akhenaten. [Source: Mindy Weisberger, Live Science, October 24, 2022]

According to Live Science: Archaeologists found KV 55 in an undecorated tomb that contained bricks engraved with magic spells bearing Akhenaten's name. Another coffin and canopic jars — vessels for holding mummified organs — contained the remains of a woman named Kiya, who was identified as Akhenaten's concubine.

KV 55 had been mummified, but the preserved flesh disintegrated in the excavators' hands, leaving only the skeleton behind. Based on objects in the tomb and the sex of the skeleton, some archaeologists concluded that it must represent Akhenaten. However, analysis of the teeth and bones revealed that the man was younger than expected. He was around 26 years old when he died — and possibly only 19 to 22 years old, whereas records suggest Akhenaten ruled for 17 years and fathered a daughter during the first year of his reign, said Francesco Galassi, director and co-founder of the FAPAB Research Center, an associate professor of archaeology at Flinders University in Australia.

Genetic analysis suggested that KV 55 was the son of Amenhotep III and the father of Tutankhamen, providing more evidence that he was Akhenaten, according to a study published in 2010 in the journal JAMA. However, this conclusion is also not without controversy, as genetic data for Egyptian mummies can be "complicated" by the fact that sibling incest was a common practice in royal dynasties, according to the statement.

Princess Kiya and the Mystery of the Two Princes and Coffin in KV 55

Princess Kiya was Akhenaten’s second wife. Dr. Marc Gabolde, wrote in for the BBC: “In texts, Kiya is given the lengthy title 'the greatly beloved wife of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Neferkheperure-Wa'enre, child of the Aten, who lives now and forever more'. She is never referred to as 'Royal Wife', as this was a title reserved exclusively for Nefertiti. Kiya's abnormally elaborate title, as long as Nefertiti's, may have been given to her to compensate for what was in fact a secondary status. On jar inscriptions, Kiya is mentioned simply as 'the Great Lady (of Naharina)'. As Naharina was also known as Mitanni, there is strong reason to believe that Kiya was princess Tadukhipa of Mitanni (Syria, southwest Anatolia), sent to the Egyptian court late in the reign of Akhenaten's father, Amenhotep III, by Tushratta of Mitanni (Naharina). After a few years in the old pharaoh's harem, she was put into that of his son.” [Source: John Ray, BBC, February, 17, 2011]

Kiya

John Ray wrote for the BBC: “Princess Kiya is a shadowy figure, whose life has been pieced together from fragments of inscriptions, some of which were erased by her contemporaries. She is now believed to be the subject of some of the inscriptions found in the most mysterious of royal tombs, number 55 in the Valley of the Kings. [Source: John Ray, BBC, February, 17, 2011]

“We encounter her only through her husband, Akhenaten, often referred to as 'the heretic king'. He came to the throne as Amenophis IV, but broke with established religion and devoted himself to a single deity known as the Aten. He was married to the beautiful Nefertiti. On many of their monuments Akhenaten and Nefertiti are accompanied by their daughters. It appears that the pair had no sons. |::|

“There are, however, two spare princes who appear in the records from Amarna, the capital city that Akhenaten founded for himself. These are Smenkhkare and Tutankhaten (the latter means 'Living image of the Aten'). They are brothers, and the likelihood is that their father is Akhenaten. |::|

“Egyptologists are coming to the conclusion that Kiya was the mother of these princes, and it is to this that she owed her influence with the king. Pharaohs were allowed several wives, and Nefertiti may have accepted this, but the situation has the potential to turn nasty. Somebody is responsible for the erasure of Kiya's names from most of her inscriptions, but we do not know who this is. Kiya died before Akhenaten. |::|

“When Akhenaten did die, he was succeeded briefly by Smenkhkare, and then by his second son, who changed his name to Tutankhamun. The discovery of the latter's tomb in 1922 made him famous, but the fate of Smenkhkare is more obscure. |Tomb 55 in the Valley of the Kings contained objects from the Amarna court, among them a damaged coffin designed for a woman, although the badly preserved body inside this turned out to be male. This may be Akhenaten, but it is more likely that the body is that of Smenkhkare. The inscription at the foot of the coffin is one originally appropriate for a woman, but later changed to refer to a man. We now suspect that the original subject is Kiya. The inscription is unique both for its poetic imagery and for the light it sheds on Akhenaten's religion. |::|

Akhenaten's Death and Legacy

In the middle of tense period with the Hittites, when Egypt’s possessions in Syria were being threatened, Akhenaten died. Historians are not sure how he died or when other than it was in the 17th year of his rule. He was buried in a Valley-of-the-Kings-style tomb cut into a cliff east of Amarna.

Akhenaten's revolution came to an end after his death. Pharaohs that succeeded him regarded him as a heretic. The temples he created for his new religion were destroyed and his name was expunged from historical records. His ideas about religion were quickly forgotten and things went back to the way they were before.

After Akhenaten’s death there was a scramble for power. A mysterious Pharaoh named Smenkhkare may have ruled briefly, for a year ir two, before dying himself. Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic, “The end of Akhenaten's reign is cloaked in confusion — a scene acted out behind closed curtains. One or possibly two kings rule for short periods of time, either alongside Akhenaten, after his death, or both. Like many other Egyptologists, I believe the first of these "kings" is actually Nefertiti. The second is a mysterious figure called Smenkhkare, about whom we know almost nothing.” [Source: Zahi Hawass, National Geographic, September 2010]

Intrigues Around the Time of Akhenaten’s Death

Little is known about the last five years of Akhenaten's reign, or the three year period after his death leading up to Tutankhamun's accession to the throne. Dr Marc Gabolde wrote for the BBC: “Many theories have been advanced and the uncertainty has been compounded by the appearance during these years of new royal personages whose origins and identity remain a matter for debate....The evidence that survives from the Amarna period is often badly damaged and in many cases throws up more questions than answers.” [Source: Dr Marc Gabolde, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Marsha Hill of The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Akhenaten's last years and certainly the period after his death give evidence of a troubled succession. Nefertiti, Meritaten, the mysterious pharaoh Smenkhkare, and the female pharaoh Ankhetkhepherure—for whom the chief candidates in discussions so far have been Nefertiti and Meritaten, the eldest daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti—and ultimately Tutankhaten all have roles. Energetic scholarly discussion of the events of this period and the identity, parentage, personal history, and burial place of many members of the Amarna royal family is ongoing. It is clear that already during the succession period, there was some rapprochement with Amun's adherents at Thebes. With the reign of Tutankhaten / Tutankhamun, the royal court left Akhetaten and returned to Memphis; traditional relations with Thebes were resumed and Amun's priority fully acknowledged. With Haremhab, Akhenaten's constructions at Thebes were dismantled, and dismantling began at Amarna. Apparently in the reign of Ramses II, the formal buildings of Akhetaten were completely destroyed, and many of their blocks reused as matrix stone in his constructions at Hermopolis and elsewhere. The site had presumably been abandoned. [Source: Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 2014, metmuseum.org \^/]

Jacquelyn Williamson of George Mason University wrote: “The years before and after Akhenaten’s death generate much discussion, especially concerning the figures known as Semenkhkara and Neferneferuaten. In the Amarna tomb of the official Meryra II, Akhenaten’s daughter Meritaten is shown married to a person named Semenkhkara, a new king. Semenkhkara appears suddenly and then vanishes from the record just as quickly. His largest monument is the so-called “coronation hall”—a vast construction at the Amarna Great Palace whose purpose is unknown. Semenkhkara could have been Akhenaten’s son or even his brother, and may have married Meritaten, his sister/niece, sometime after year 12. He may have served briefly as a coregent, crowned alongside Akhenaten and helped him to rule Egypt for a brief time. Semenkhkara may have died early from illness, perhaps the epidemic mentioned above, cutting short his tenure as coregent and king. [Source: Jacquelyn Williamson, George Mason University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

“An additional controversial royal figure named King Neferneferuaten appeared at the end of Akhenaten’s reign. Although some have argued that Neferneferuaten can be conflated with the male king Semenkhkara, it is clear from several inscriptions that Neferneferuaten was indeed female. The phenomenon of a woman holding the male title of king was not unknown in Egypt; one of the earlier kings of the 18th Dynasty, Hatshepsut, was a woman. King Neferneferuaten could thus have been Meritaten’s throne name if, as some suggest, she succeeded her father to the throne.

“Another possibility is that Neferneferuaten was Nefertiti, who was already using the throne name “Neferneferuaten Nefertiti” from year 5 of Akhenaten’s reign. She may have retained the name Neferneferuaten when crowned king, perhaps as a coregent to fill a power vacuum left by the death of Semenkhkara. However a jar docket dated to Akhenaten’s year 17 was emended to say “year 1,” which could indicate direct succession rather than a joint rule. In other words, according to this jar docket Neferneferuaten was not named coregent after the death of Semenkhkara, but assumed the throne only after Akhenaten’s death. Supporting this last argument, and assuming Neferneferuaten is indeed Nefertiti, an inscription recently found in the Amarna Period quarries near Deir Abu Hinnis indicates that Nefertiti was probably still alive in year 16 and was still using her queenly title and names. If Nefertiti had not yet adopted a kingly identity by year 16, only one year before the death of her husband, she was not a coregent or a king at that time, lending support to the direct accession theory.

“Whatever the identity of King Neferuneferuaten, she ruled only briefly. A graffito from the tomb of Para in Thebes, TT 139, indicates that King Neferneferuaten, whomever she was, spent some of her third regnal year in Thebes. This also indicates that at least some members of the Amarna royal family returned to Thebes very soon after the death of Akhenaten. King Neferneferuaten disappears from the historical records after the graffito in TT 139, so she did not rule for long. However, also based on this graffito, not only did Neferneferuaten return to Thebes, she may have started the process of returning Egypt to its traditional religious practices. She may have also even served as coregent to Tutankhaten / Tutankhamen when he first took the throne.”

Tutankhaten and Akhenaten’s Legacy

Jacquelyn Williamson of George Mason University wrote: “Seven-year-old Tutankhaten began his rule during or after the rule of Neferneferuaten. He changed his name from Tutankhaten “The Living Image of the Aten” to Tutankhamen “The Living Image of Amun” and returned the country to its pre-Amarna status quo. Official decrees announcing the return to orthodoxy were spread throughout the country; the “Restoration Stela” in the Cairo Museum, CG 34183, preserves an example of one such decree. Tutankhamen ruled for nine years, and the tomb of the young king remained largely intact until it was discovered in the twentieth century. At Tell el-Amarna only a ring bezel and a mold bear the name Tutankhamen (rather than his earlier name Tutankhaten), indicating that after he changed his name the king was not very active at his father’s city. His return to the traditional occupation and religious centers of Egypt terminated the use of the necropolis at Tell el-Amarna. The rock-cut tombs at Amarna appear to have been unfinished, likely abandoned by their owners when the royal family reverted to its traditional beliefs. Even the royal burials at Tell el-Amarna may have been exhumed and returned to Thebes. [Source: Jacquelyn Williamson, George Mason University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

“Tutankhamen was likely too young to orchestrate such sweeping changes. Instead the officials Aye and Horemheb could have been responsible for the return to orthodoxy. Possibly the enigmatic Neferneferuaten, mentioned above, was involved as well. Aye and Horemheb were both military men, and Horemheb was an “jrj-pat “or “hereditary nobleman” and member of the ruling elite. He possessed an extensive list of additional elite titles that gave him the equivalent status to that of regent and the king’s oldest son. Horemheb’s wife, Mutnodjmet, may have been Nefertiti’s sister, which would explain his close association with the royal family. Aye had fewer titles, but he used his title “God’s Father” extensively, which may indicate that he was both Nefertiti’s father, Tutankhamen’s grandfather, and possibly the father-in-law of Horemheb. Certainly he is more prominent in Tutankhamen’s monuments than Horemheb, even appearing on a fragment of gold foil with the image of Tutankhamen from KV58 and on several blocks from Karnak pylon IX, where he is shown following Tutankhamen. Aye’s tomb (TA 25) at Tell el-Amarna indicates that he was also called a “Fan Bearer on the Right Hand of the King” and the “Real Royal Scribe,” both indications of close affiliation with the highest ranks of royal administration.

“Another subject of contention surrounding the end of the Amarna Period and possibly the death of Tutankhamen concerns several letters from an unnamed queen of Egypt to the Hittite king Suppiluliuma at Bogazköy. In these letters the Egyptian queen asks the Hittites to send her a son to marry and make king of Egypt. Accordingly the Hittite Prince Zananzash was sent to Egypt, but a subsequent letter, also preserved from Bogazköy, suggests he was assassinated en route. The Egyptian queen in question is likely to have been either Meritaten, who may have sought a husband following Semenkhkara’s death to fill the power vacuum left by the death of Akhenaten’s new coregent, or her sister Ankhesenamen (born Ankhesenpaaten), the widow of Tutankhamen, who perhaps feared her future without a clear heir to her young husband. Ankhesenamen may have married Aye instead of the Hittite prince, but the ring that bears their two names together is the last attributed mention of the young queen.

“In an attempt to forget this period of iconoclasm the successors to Akhenaten removed his name and the names of Tutankhamen and Aye from the lists of legitimate kings. Horemheb, Ramses II, and many others also used stone from Akhenaten’s monuments as fill for their own building programs. These buildings inadvertently protected Akhenaten’s legacy for thousands of years. As a result, with these “talatat “and the site of Tell el-Amarna, we know more about the Amarna Period than many other periods in Egyptian history.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024