Home | Category: New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut)

AKHENATEN'S MOVE TO AMARNA

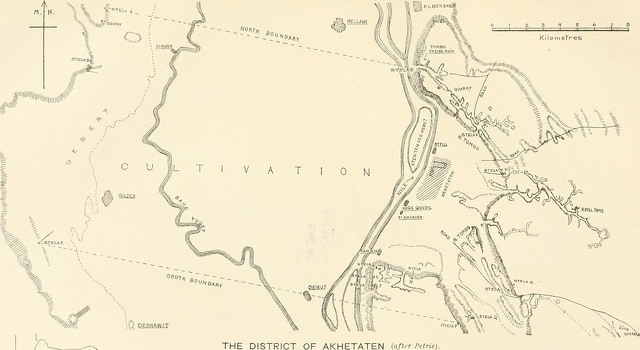

Akhenaten (ruled 1353–1336 B.C.) was son of Amenhotep III. He began his rule under the name Amenhotep IV. He defied tradition by establishing a new religion based on the belief in one and only god; the sun god Aten. After formally declaring his new religion, Akhenaten moved his capital from Thebes more than 320 kilometers (200 miles) to north to Amarna in a desert area on the east side of the Nile River. Jacquelyn Williamson of George Mason University wrote: “ In year 5 on the 13th day of the 4th month of the season of “peret”, the king announced his intention to move the court to the city he named “Akhetaten” or “The Horizon of the Aten” at Tell el-Amarna in Middle Egypt. Sixteen boundary markers, or stelae, recorded the foundation of the site and Akhenaten’s building plans. According to Akhenaten, the Aten itself dictated this move because it wanted its cult relocated to virgin territory. However, politics may have been behind the relocation, as the elite Theban population may have started resisting Akhenaten’s changes. This contention is supported by a speech recorded on Boundary Stelae K, M, and X, where Akhenaten denounces what appear to be elite-generated aspersions on his kingship. [Source: Jacquelyn Williamson, George Mason University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

Dr Kate Spence of Cambridge University wrote for the BBC:“Akhenaten decided that the worship of the Aten required a location uncontaminated by the cults of traditional gods and to this end chose a site in Middle Egypt for a new capital city which he called Akhetaten, 'Horizon of the Aten'. It is a desert site surrounded on three sides by cliffs and to the west by the Nile and is known today as el-Amarna. In the cliffs around the boundaries of the city the king left a series of monumental inscriptions in which he outlined his reasons for the move and his architectural intentions for the city in the form of lists of buildings. [Source: Dr Kate Spence, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

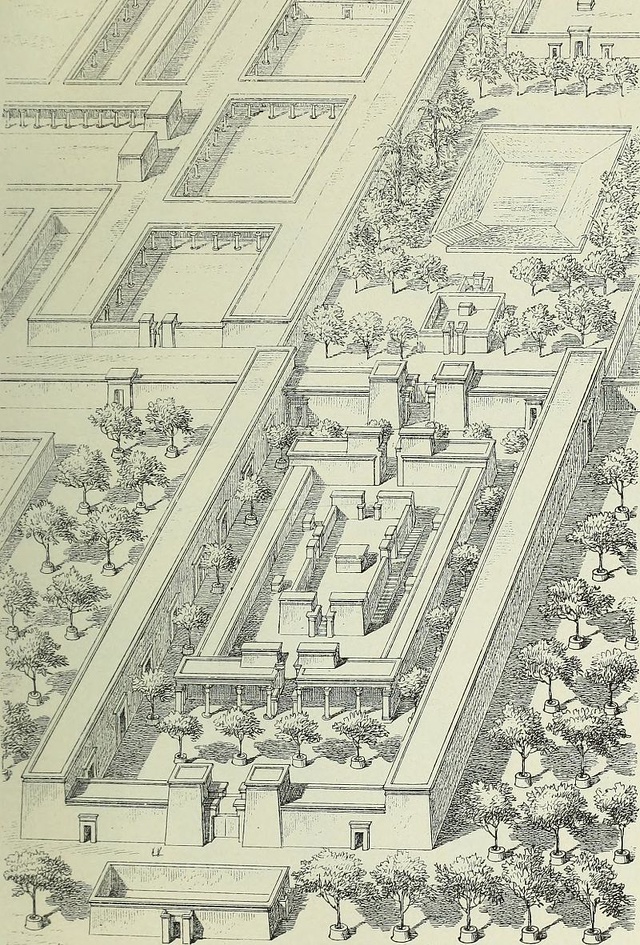

“To the east of the city is a valley leading into the desert in which the king began excavating tombs for the royal family. On the plain near the river massive temples to the Aten were constructed: these were open to the sky and the rays of the sun and were probably influenced by the design of much earlier solar temples dedicated to the cult of Re. Other sites of religious importance are located on the edges of the desert plain. There were also at least four palaces in the city which vary considerably in form, plus all the administrative facilities, storage and workshops necessary to support the royal family, court and the temple cults. |::|

Marsha Hill of The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: A set of fifteen boundary stelae marking the first anniversary of the proclamation, stood in the cliffs enclosing the large plain on either side of the Nile at the site. Naming himself Akhenaten and thus referring to the Aten, and abjuring his previous name Amenhotep referring to that god, the king proclaimed the founding and layout of a city he called Akhetaten, or Horizon of the Aten: he prescribed temples for the Aten, a so-called sunshade shrine in the name of Nefertiti, palaces, burial places for the royal family and high officials, and festivals and ritual provisions for the Aten. Over the twelve years between the date of the first proclamation and Akhenaten's death in year 17 of his reign, this program was largely fulfilled. [Source: Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 2014, metmuseum.org \^/]

RELATED ARTICLES:

AKHENATEN (1353 B.C. TO 1336 B.C.): HIS LIFE AND MYSTERIES SURROUNDING HIS FAMILY AND DEATH africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AKHENATEN AND MONOTHEISM africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NEFERTITI: HER LIFE, BEAUTY, BUST AND MARRIAGE TO AKHENATEN africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AKHENATEN'S REIGN (1353 B.C. TO 1336 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Amarna: A Guide to the Ancient City of Akhetaten” by Anna Stevens (2021) Amazon.com;

“The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and Its People” by Barry Kemp Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten: A Historian's View” by Ronald T. Ridley, Aidan Dodson, Salima Ikram Amazon.com;

“Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen” by Rita E. Freed and Yvonne J. Markowitz (1999) Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten: King of Egypt” by Cyril Aldred Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt” by Dominic Montserrat (2000) Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten: The Heretic King” by Donald B. Redford (1984) Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten and the Religion of Light” by Erik Hornung and David Lorton (2001) Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten and the Origins of Monotheism” by James K. Hoffmeier Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten: Egypt's False Prophet” by Nicholas Reeves and C. N. Reeves Amazon.com;

“Son of God, Son of the Sun: The Life and Philosophy of Akhenaten, King of Egypt”

by Savitri Devi, David Skrbina (2023) Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Golden Couple: When Akhenaten and Nefertiti Were Gods on Earth”

by John Darnell and Colleen Darnell Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten, Dweller in Truth” by Naguib Mahfouz (1985), Novel by Nobel Prize winner Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom" by Joyce Tyldesley (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume III: From the Hyksos to the Late Second Millennium BC” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt: A Captivating Guide” Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

Amarna

Amarna (40 miles south of Al-Minya, near the town of Mallawi) was the royal city built on the Nile by Akhnaten to honor the god Aten and promote Akhnaten’s belief in a single god. A year or two after it was established as a religious center Amarna grew into a city with 20,000 people. The pharaoh lived with his wife and daughters in a luxurious palace with zoos, swimming pools, sunken gardens, bakeries and breweries.

At its height the ancient city stretched for eight miles along the Nile and extended three miles inland. A road along the river led to palaces and temples. The largest temple was an open air structure some 2,500 feet long and 950 feet wide. It contained a large courtyard where

After Akhenaten died, the polytheistic pharaohs that followed him destroyed many things associated with Akhenaten and his worship of one god. Even so a great deal of the foundations of city and its temples, palaces and noble tombs remain because the city was abandoned after Akhenaten's death and no one bothered to build anything on top of it. Tombs in the area feature artwork and inscribed stelae a wonderful style of exaggerated naturalism, now referred to as new the "Amarna style." Nearby is a temple built by Ramses II to honor Thoth, a local god and the god of wisdom of knowledge. More tombs can be seen in Al-Haj Qandil.

See Separate Article: AMARNA: LAYOUT, BUILDINGS, AREAS, HOUSES, INFRASTRUCTURE africame.factsanddetails.com

Tell el-Amarna

Tell el-Amarna is the archaeology site at Amarna. Anna Stevens wrote: Tell el-Amarna is situated in middle Egypt and is the location of the New Kingdom city of Akhetaten, founded by Akhenaten in around 1347 B. C. as the cult home for the Aten. Occupied only briefly, it is our most complete example of an ancient Egyptian city, at which a contemporaneous urban landscape of cult and ceremonial buildings, palaces, houses, cemeteries, and public spaces has been exposed. It is an invaluable source for the study of both Akhenaten’s reign and of ancient Egyptian urbanism. The site has an extensive excavation history, and work continues there today. [Source: Anna Stevens, University of Cambridge, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship. org ]

Amarna is one of the most extensively investigated archaeological sites in Egypt. Early European expeditions, from the late eighteenth century, concentrated on surveying the city and copying its key monuments, especially the Boundary Stelae and rock-cut to mbs. The Napoleonic survey of 1798/1799 made the first substantial record of the site, publishing a partial plan of the city ruins in the Description de l’Égypte in 1817. In the 1820s, John Gardner Wilkinson re surveyed the city and copied some of its monuments, with James Burton copying the tomb of the official Meryra (no. 4).

“Barry Kemp has directed an annual program of survey, excavation, and conservation at Amarna since 1977, under the auspices of the EES until 2006, and as the Amarna Project thereafter. This work has seen focused excavation across the site: prim arily, at the Workmen’s Village, housing areas and workshops in the Main City, the Small Aten Temple and its surrounds, the North Palace, Kom el-Nana, the Great Aten Temple, and at the city’s non-elite cemeteries. The second half of the nineteenth century has also seen campaigns by the Egyptian Antiquities Organization, Paul Nicholson’s investigations of glass and faience workshops , and a study of the Coptic remains at the North Tombs.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Tell el-Amarna by Anna Stevens escholarship.org

Akhetaten (Horizon of the Aten)

In Armana, Akhenatan built a new city, which he called Akhetaten, “Horizon of Aten.” Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “The new city had many spacious villas with trees, pools, and gardens. Akhenaten encouraged artistic inventiveness and realism and the walls of the temples and houses were painted in an eccentric new style. Among the surviving works of this period are the colossal statues of Akhenaten, the paintings from his private residence, the bust of his wife Nefertiti, and that of his mother, Queen Tiy. These works are unique in Egyptian art, as they do not flatter the king and his family but reveal them as real people, in all their beauty and decay.” [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Jacquelyn Williamson of George Mason University wrote: ““The new city at Tell el-Amarna was located on a desert plain in a semicircular area defined by the river and a large amphitheater of cliff faces. Tombs of the elite were placed in the northern cliffs and in the southern desert hills...It appears that most members of the Theban elite accompanied the king to Tell el- Amarna. Some, such as Parennefer, started new tombs at Amarna. Not every member of the elite followed Parennefer’s example, however. The official Ramose, whose Theban tomb represents Akhenaten before and after his artistic revolution, is not attested at Amarna. Kheruef did not relocate to Amarna either, and the intentional damage to his tomb may indicate the ramifications of his refusal to accompany the king to his new city. On the other hand, at Memphis some of Akhenaten’s officials kept their tombs without reprisal, which may indicate that Akhenaten did not require his Memphis officials to move to Amarna. [Source: Jacquelyn Williamson, George Mason University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

Marsha Hill of The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “In its initial formal plan, the city stretched from north to south along a royal road that led from a huge palace—termed the North Riverside Palace—at the north, through the Central City with the Great Aten Temple, the Small Aten Temple, the Great Palace (the ceremonial palace), and the administrative and provision quarters, to a southern temple for Nefertiti at Kom el-Nana. Over the years, the road to the south was obscured by a growing suburb, but certainly the Royal Road from north to the Central City constituted a sort of processional route where the king and his family in their chariots could be seen progressing to and from the temple. Most of these buildings have been excavated to some degree. [Source: Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 2014, metmuseum.org \^/] Dr Kate Spence of Cambridge University wrote for the BBC: “Akhetaten is sometimes described as if it were some sort of broad Utopian project. However, while temple and palace areas of the city are clearly planned, there is actually no evidence that Akhenaten showed any interest in the living arrangements of his people and residential areas suggest organic urban development. The wealthy seem to have enclosed an area of land with a high wall and built their spacious houses and ancillary structures within, while the houses and shacks of those that followed the court are crammed in between these luxurious walled estates. The city was probably less dense than other urban centres of the day but this was only because it was inhabited for such a short time and processes of infilling were in their infancy. Amarna is one of the few sites where we have a significant amount of archaeological information about how people actually lived in ancient Egypt. [Source: Dr Kate Spence, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Amarna as a Thriving Egyptian City

Marsha Hill of The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Not only was Akhetaten the center for worship of the Aten and the dwelling place of the king, it was the home of a large population—an estimated 30,000 people, nowhere signaled in the provisions of the boundary stelae. When the city was abandoned after about two decades, the streets and structures with their archaeological evidence were preserved in the state in which they were left after removal of much of the stonework and destruction of statuary. Because the city was not impacted by use over long periods of evolution, the site constitutes a remarkable laboratory for observation of an ancient society, albeit a very particular one created from the ground up at a specific moment. [Source: Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 2014, metmuseum.org \^/]

“A large population of officials and their dependents migrated to the city with the king. Villas of officials were scattered throughout the city; each villa or every few villas had a well, and that nucleus was then surrounded by smaller houses arranged according to the lights of their inhabitants. Amarna's excavator Barry Kemp has aptly described clusters thus formed as village-like, and he has referred to the city they formed as an "urban village." The grouping of smaller houses around an official's house points to the attachment of dependents to a given official, but also to the fact that the members of the complex were all aware of each other as interdependent in a way common to small villages. These village-like complexes produced statuary; stone, faience, and glass vessels, jewelry, or inlays; metal items, and the like. Usually several industries operated in the same complex, serving the furnishing and embellishment of the royal buildings and other needs; by providing for these workers, the official heading the complex must have had rights to the things produced, which he then provided toward the court undertakings.

“The city offers a good deal of information about the spiritual concerns of its people, although the disparate evidence leaves many gaps and questions. As for involvement in the official Aten religion and the temples, officials presumably commissioned some of the temple statuary of the royal family or small-scale temple equipment at workshops distributed throughout one whole zone of the city. Some of the society at least also seems to have had particular access to certain parts of the temple: the Stela Emplacement area toward the back is one example already noted. Certain figured ostraka or carved single ears—known elsewhere as dedications asking for a god's attention to prayers—may likewise be offerings deposited at some locale in the temples . Moreover, the huge bakeries attached to the Great Aten Temple, along with the many hundreds of offering tables in the temple, point to wide distributions of food, and these could be tied to broad accommodation within areas of the temple enclosure, possibly in connection with the festivals of the Aten promised on the boundary stelae. In their homes, officials might exhibit devotion to the royal family as the children of the Aten, sometimes constructing small chapels in gardens alongside their houses for their own or perhaps neighborhood use. And at least one structure located in the city's bureaucratic and military district was a sort of neighborhood shrine for a cult of the king. From the perspective of the small finds attached to houses and burials of the wider populace, there is very little overt evidence of attention to the new god, although such attention might not be well manifested in such finds for a variety of reasons. What is clear is that there was no absolute prohibition on other gods: material remains testify to continued interest in household gods like Bes and Taweret, protector deities like Shed and Isis, and belief in the efficacious magic of female or cobra figurines. The practice of honoring and invocation of important ancestors and probably other figures in the community through statues or stelae in household shrines or elsewhere seems to have pervaded society, and points to a better understanding of the phenomenon usually termed "ancestor worship". \^/

“Recent excavations have revealed the long-unknown cemeteries of the general populace. The royal and elite tombs have long been known: the royal tomb for Akhenaten along with other partly finished tombs lay in the Royal Wadi through the cliffs to the east of the city and probably held the king's body along with a number of his daughters and his mother, but these interments were removed; two groups of fine tombs for a number of the great officials lined the cliffs to the east of the city, although most of the owners were not actually buried there before habitation at the site was ended. In contrast, the recently excavated South Tombs Cemetery of the general populace shows ample evidence of use, probably holding about 3,000 individuals. A few of these individuals had coffins or stela or a piece of jewelry; most were simply wrapped, apparently not mummified, in a mat of rushes which served as a sort of coffin and accompanied by a few pots. While there was certainly no mention of traditional funerary religion involving Osiris in the royal or elite tombs, there was some variability in the South Tombs Cemetery: one burial had a coffin apparently representing the Sons of Horus. The remains present many points of interest, but perhaps most surprising is the evidence of duress and poor diet well beyond that known for other typical New Kingdom populations. The profile of the population in terms of age at death also indicates to researchers that an as yet unidentified epidemic scoured the population. Other cemeteries have been identified, and more excavation is anticipated.” \^/

Akhenaten’s Great Aten Temple in Amarna

Marsha Hill of The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “A central structure of the city was the Great Aten Temple...The temple's precinct encompassed a vast expanse in which traces of two complexes can be seen, one in the front third and one at the rear. In both areas, there were initial works in mud brick, which were later replaced with stone buildings. Current work at the site has revealed that at least the front building, known as the Long Temple or Gem-Aten, was substantially rebuilt again fairly late in the reign for reasons that are as yet unclear. These substantial changes over the short span of eleven years suggest the temple was a construction site for most of its existence. [Source: Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 2014, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The entire temple was open to the sky. In what we understand as its final state, one entered the temple enclosure through a mud-brick pylon, and advanced through a forecourt filled with numerous large low basins toward two colonnades of huge columns on either side of the axis. Beyond the colonnades stretched a long progression of courts filled with offering tables and punctuated by large altars. Fields of hundreds of offering tables aligned the Long Temple, though whether on both sides simultaneously is not clear. Then, beyond a huge stretch of ground, unexcavated and more or less featureless to the modern eye, stood a second building known as the Sanctuary of the Great Aten Temple. Within its own walled area, the Sanctuary was raised on a high gypsum cement podium. The building was fronted by a porch with columns and colossi of the king, and within, under the open sky, opened a court with small offering tables and a large altar, surrounded by twelve chapels. The Sanctuary seems to have been completed before the Long Temple, and certainly its plan suggests it was a successor of the Karnak platform temple. Not far outside the Sanctuary enclosure wall was a site where a large stela with an offering list stood on a podium alongside a seated statue of the king. The stela site was on an axis with an unusual entry building in the side wall of the main enclosure wall; it has been conjectured that this entry building allowed access to the stela and statue area, possibly by those wishing to participate in the king's cult. A butcher yard within the temple enclosure and huge bakeries outside saw to the needs of the Aten cult. \^/

“The Great Aten Temple was adorned with reliefs. Some scenes and inscriptions in the Long Temple were spectacularly inlaid with colored stones, glass, and faience; some from the Sanctuary were gilded. Not long after the Amarna Period, the reliefs were removed for reuse as building matrix for other constructions, but the stones left at the site attest to many scenes of presentation of offerings or performance of ritual actions by the king and queen under the Aten's rays. Scenes of nature and large intimate family tableaux are also attested. Fragments document statues in quartzite, granite, granodiorite, and particularly in beautiful hard white limestone known as indurated limestone, a specialty of the two Aten temples. The Metropolitan Museum has many indurated limestone sculptural fragments from the Sanctuary of the Great Aten Temple, where they were broken up on site by the temple's destroyers. These indicate that sculptors continued to adopt expressive forms to represent the royal couple's relation to their deity—the king's and queen's narrowed eyes and arching bodies with locked knees evoke a certain otherness, even if we do not understand the direct import of these features. But, in fact, the fragments also show considerable stylistic variability. Poses of the Great Aten Temple statuary as they can be reconstructed are often new to Egyptian art and surely express meaningful ritual actions within the definitions of the new cult: the king and queen as a dyad with their arms raised high before them and tall pillars inscribed with the Aten's names stretching from their fingertips to toes; the king prostrate before the god; the king with arms raised in adoration. \^/

Akhenaten’s Great Palace

Marsha Hill of The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The ceremonial palace—the Great Palace—stood near the Great Aten Temple. This was the largest building in the city, and was elaborately decorated with relief and statuary, fine stone balustrades, stone, faience and glass inlay, gilding, and wall and pavement paintings. As the current excavator notes, it was designed to impress. This was the ceremonial or reception palace of the royal family, who seem to have lived elsewhere. The palace was entered from the north. Those arriving ascended ramps to pass through a monumental entrance decorated with columns, reliefs, and perhaps seated statues. They then descended ramps into the Broad Court, where great colossi in quartzite and granite stood, preserved only in fragments but reminiscent of those in the Karnak Heb Sed court. At the southern end of the Broad Court was a large porticoed balcony that may have been one of the locales termed a "window of appearance," where the king and his family appeared to a larger public. The Broad Court complex at the Great Palace has been suggested as a site for official awards and feasting. To the east, the palace adjoined the Royal Road; on the western side, to judge from relief depictions, porticoes lined the riverfront. [Source: Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 2014, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Less is known about the sunshades—an ancient Egyptian term for a place for sun worship—of the royal women. One at least, the Maruaten, evoked a lush natural setting with water and plants and a sort of island. The Kom el-Nana, certainly Nefertiti's shrine, has provided evidence of a particular type of statuary associated with Amarna known as composite statuary, where lifelike skin coloring and textures, garments, and poses are mimicked by attaching separate pieces in different stones. Whether composite or no, statues in warm-colored stones such as yellow-brown or deep red quartzite of the king and queen and their daughters, often in groups and often linked by intimate gestures of held hands or interlaced arms, are a type that flourished at the site of Amarna itself, wherein the special intimacy and beauty of the family expresses their status as the beloved children of the Aten. \^/

“Reliefs decorated all the temples and palaces, and wall, floor, and ceiling paintings adorned many of the palaces. Although the buildings were torn down after the end of the Amarna Period, the stone itself was removed to other sites to be used as fill in constructions. So, while it has not yet been possible to reconstruct larger scenes and their coordination with particular spaces as it was at Karnak, some sense of the themes represented is available. The life of the royal family, the beautiful children of the Aten, in the company of their god is central, from intimate depictions of the king and queen with the young princesses, to their movement through the city in chariots to the temples, to scenes of ritual and offering under the rays of the Aten . Scenes of nature under the Aten's rays figure largely: dewy grapes, gamboling animals, startled birds, and scenes in the marsh. Ambient activities are represented in similar spirit: busy cleaners and porters at the palace, soldiers sleeping alongside their smoking fires, attendants tending burning coals, boat and dock scenes.

Akhenaten and Amarna Archaeology and Research

Jacquelyn Williamson of George Mason University wrote: “ In 1714, Jesuit priest Claude Sicard was the first non-Egyptian to describe the Amarna Period monument that Baudouin van de Walle later labeled as “Boundary Stela A”. One of many such boundary markers distributed around the site of Akhenaten’s ancient city at Tell el-Amarna, Boundary Stela A shows the royal family offering to the Aten and features an inscription discussing Akhenaten’s intentions to found a city dedicated to the Aten. A century following Sicard’s discovery, some of the others to visit the site included Napoleon Bonaparte’s Expedition d’Égypte, which documented Tell el-Amarna in “Description de l’Égypte “(1809-1828), and John Gardner Wilkinson, who visited the North tombs in 1824. [Source: Jacquelyn Williamson, George Mason University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

“The art of a traditional Egyptian official’s tomb features a celebration of the owner’s life and focuses on ensuring his success in the afterlife. Amarna tombs focus on the royal family’s daily life and worship of the single solar god, the Aten, with minimal attention paid to the owner of the tomb or their family. The unusual nature of Akhenaten’s art inspired the later work of K. R. Lepsius, who delivered a seminal lecture in 1851 arguing that Akhenaten was a monotheist. This was the first entry to a debate that continues today on the nature of Atenism and its relationship to traditional Egyptian polytheistic religion.

“Interest in Tell el-Amarna was rekindled toward the close of the nineteenth century when local residents discovered Akhenaten’s tomb in the 1880s. In 1887 they also found the first of the Amarna Tablets, also called the Amarna Letters. These documents are among the most significant preserved accounts concerning diplomatic relations between New Kingdom Egypt and the rest of the ancient Near East. Flinders Petrie excavated extensively at Tell el-Amarna starting in the early 1890s. His excavations included the Great Aten Temple, the royal archives, and the King’s House. Petrie’s work generated even wider interest about Akhenaten and his religion.

“”Solem sub Rege Amenophide IV”. He characterized Akhenaten as a precursor to Saint Francis of Assisi and as history’s “first individual.” Norman de Garis Davies produced six illustrated volumes about the rock-cut private tombs at Amarna, titled “The Rock Tombs of El Amarna”, with the first volume appearing in 1903. On the basis of the findings of Petrie and the art of the private tombs surveyed by Davies, in 1905 Adolf Erman labeled Akhenaten a religious “fanatic.” Ludwig Borchardt, who worked for the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft, began systematically surveying the city of Tell el- Amarna in 1911. He discovered Thutmose’s workshop and the famous Berlin head of Nefertiti. After World War I ended in 1918, the Egypt Exploration Society began excavating at Tell el-Amarna. They produced three volumes detailing the results of their work titled “The City of Akhenaten”, released in 1923, 1933, and 1951.

“Discoveries from Akhenaten’s city were not confined to the site of Amarna itself. Akhenaten constructed his monuments out of smaller stone building blocks than kings before him. Measuring approximately 53 centimeters long by 21 centimeters high and 24 centimeters deep, these “talatat “blocks (named for the Arabic word for three, “talata”, as they are approximately three handspans long) are easier to move than the larger blocks used by the kings before Akhenaten. This innovation allowed Akhenaten to build his monuments rapidly. However this also meant that his monuments were easy to demolish. In 1939 Günther Roeder discovered 1500 of these “talatat “at Hermopolis; Ramses II had used the “talatat “from the abandoned Tell el-Amarna to build the foundations for his temple across the river at Hermopolis. Roeder published the discovery of these blocks in “Amarna-Reliefs aus Hermopolis”.

“Since 1977, Barry Kemp, first with the Egypt Exploration Society and now the Amarna Trust, has directed the work at Tell el- Amarna. Several scholars have reexamined the royal tombs at Amarna. Recent research has revealed new discoveries and new understandings of old discoveries, such as the discovery of Boundary Stela H, a Coptic monastery and church, the first Amarna “citizen’s cemetery”, the “Sunshade of Ra” or the sun temple of Queen Nefertiti, and the “rwd anxw jtn”, a structure associated with Nefertiti’s sun temple dedicated to the maintenance of the afterlives of Akhenaten’s citizens.

Was Child Labor Used to Build the Ancient Egyptian City of Amarna?

There is evidence that a ‘disposable’ workforce of children and teenagers provided much of the labor to build Amarna. Mary Shepperson wrote in The Guardian: “Amarna came and went in an archaeological moment. It rose and fell with Akhenaten and his religious reformation, under which Egypt’s ancient pantheon of gods was briefly usurped by the worship of a single solar deity; the Aten. Between 2006 and 2013 I was lucky enough to work for the Amarna Project on an excavation which aimed to recover four hundred individuals from a large cemetery behind the South Tombs cliffs, estimated to contain around six thousand badly looted burials. The study of these burials and their human remains has opened a new research window on life and death in the lower echelons of Egyptian society. They paint a picture of poverty, hard work, poor diet, ill-health, frequent injury and relatively early death. [Source:Mary Shepperson, University of Liverpool, The Guardian, June 6, 2017]

“In other respects the South Tombs Cemetery remains were fairly in line with expectations. There were modest variations in the wealth and style of burial, there was a fairly even mix of male to female individuals, and the age distribution showed the usual pattern for ancient populations; high infant mortality giving way to fewer deaths as children survive into early adulthood, with the death rate then rising again as adults succumb to illness, childbirth, injuries and age. This was all important and highly interesting, but not particularly unusual.

“In 2015 we began excavating another non-elite cemetery in a wadi behind a further set of courtiers’ tombs at the northern end of the city, and here the tale takes a stranger turn. As we started to get the first skeletons out of the ground it was immediately clear that the burials were even simpler than at the South Tombs Cemetery, with almost no grave goods provided for the dead and only rough matting used to wrap the bodies.

“As the season progressed, an even weirder trend started to become clear to the excavators. Almost all the skeletons we exhumed were immature; children, teenagers and young adults, but we weren’t really finding any infants or older adults. Our three excavation areas were far apart, spaced across the length of the cemetery, but comparing notes all three areas were giving the same result. This certainly was unusual and not a little bit creepy.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Did children build the ancient Egyptian city of Amarna? By Mary Shepperson, in The Guardian theguardian.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024