Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

AMARNA (AKHETATEN, TELL EL-AMARNA)

Armana center today

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “Tell el-Amarna is the site of the late 18th Dynasty royal city of Akhetaten, the most extensively studied settlement from ancient Egypt. It is located on the Nile River around 300 kilometers south of Cairo, almost exactly halfway between the ancient cities of Memphis and Thebes, within what was the 15th Upper Egyptian nome. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Founded by the “monotheistic” king Akhenaten in around 1347 BCE as the cult center for the solar god, the Aten, the city was home to the royal court and a population of some 20,000-50,000 people. It was a virgin foundation, built on land that had neither been occupied by a substantial settlement nor dedicated to another god before. And it was famously short-lived, being largely abandoned shortly after Akhenaten’s death, some 12 years after its foundation, during the reign of Tutankhaten; a small settlement probably remained in the south of the city. Parts of the site were reoccupied during late antique times and are settled today, but archaeologists have nonetheless been able to obtain large expo sures of the 18th Dynasty city. Excavation and survey has taken place at Amarna on and off for over a century, and annually since 19.

“The ancient name Akhetaten (Axt jtn : Horizon of the Sun’s Disc) seems to have referred both to the city itself and its broader territory, which was roughly delineated by a series of Boundary Stelae cut in the cliffs around the settlement. The archaeological si te has been known as Tell el-Amarna since at least the early nineteenth century CE. The name is probably connected to that of the Beni Amran tribe who settled in this part of Egypt around the beginning of the eighteenth century CE and founded the village of el-Till Beni Amran (now usually shortened to el-Till) on the ruins of Akhetaten. The name Tell el-Amarna is often abbreviated to Amarna or el-Amarna, to avoid giving the impression that it is a tell site in the sense of a mound of ancient remains. The archaeological landscape of Amarna is a fairly flat one, reflecting the largely single-phase occupation of the site.

From a historical viewpoint, Akhetaten was never one of ancient Egypt’s great cities or religious centers, rivaling Thebes or Memphis. The importance ascribed to Amarna originates largely from modern scholarship, for two main reasons. The first is that it formed the arena on which one of the most unusual, and in some respects transformative, episodes in ancient Egyptian history played out. The second is its contribution to the study of urbanism in the ancient world.

“In addition to its historical significance, Amarna is our most complete example of an ancient Egyptian city. Allowing for its unusually short period of occupation, and the particulars of Akhenaten’s reign, it serves as a fundamental case site for the study of settl ement planning, the shape of society, and the manner in which ancient Egyptian cities functioned and were experienced. Overall, the city has a fairly organic layout, albeit with hints of planning: the line of the Royal Road seems to have formed an axis al ong which key buildings such as the North Palace, the temples and palaces of the Central City, and the Kom el-Nana complex were laid out, and it is probably not a coincidence that the axis of the Small Aten Temple lines up with the mouth of the Royal Wadi. Scholarly opinion differs, however, on the extent to which the city was formally designed, and particularly how far it was laid out according to a symbolic blueprint befitting its status as cult home for the Aten. Less contentious is the observation that the residential areas of Akhetaten developed in a fairly piecemeal manner, the smaller houses built abutting one another, often fitting into cramped spaces, and with thoroughfares developin g in the areas between —although the city presumably never reached the kind of urban density of long-lived settlements such as Thebes and Memphis.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Amarna: A Guide to the Ancient City of Akhetaten” by Anna Stevens (2021) Amazon.com;

“The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and Its People” by Barry Kemp Amazon.com;

“The Complete Cities of Ancient Egypt” by Steven R. Snape (2014) Amazon.com;

“Cities and Urbanism in Ancient Egypt” by Manfred Bietak, Ernst Cerny, Irene Forstner-Muller (2010) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Towns and Cities” by Eric Uphill (2008) Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten: A Historian's View” by Ronald T. Ridley, Aidan Dodson, Salima Ikram Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten: King of Egypt” by Cyril Aldred Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten and the Religion of Light” by Erik Hornung and David Lorton (2001) Amazon.com;

“Thebes in Egypt: A Guide to the Tombs and Temples of Ancient Luxor” by Nigel Strudwick (1999) Amazon.com;

“Abydos: Egypt's First Pharaohs and the Cult of Osiris” by David O'Connor (2009) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Amarna as a Thriving Egyptian City

Marsha Hill of The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Not only was Akhetaten the center for worship of the Aten and the dwelling place of the king, it was the home of a large population—an estimated 30,000 people, nowhere signaled in the provisions of the boundary stelae. When the city was abandoned after about two decades, the streets and structures with their archaeological evidence were preserved in the state in which they were left after removal of much of the stonework and destruction of statuary. Because the city was not impacted by use over long periods of evolution, the site constitutes a remarkable laboratory for observation of an ancient society, albeit a very particular one created from the ground up at a specific moment. [Source: Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 2014, metmuseum.org \^/]

“A large population of officials and their dependents migrated to the city with the king. Villas of officials were scattered throughout the city; each villa or every few villas had a well, and that nucleus was then surrounded by smaller houses arranged according to the lights of their inhabitants. Amarna's excavator Barry Kemp has aptly described clusters thus formed as village-like, and he has referred to the city they formed as an "urban village." The grouping of smaller houses around an official's house points to the attachment of dependents to a given official, but also to the fact that the members of the complex were all aware of each other as interdependent in a way common to small villages.

“The city offers a good deal of information about the spiritual concerns of its people, although the disparate evidence leaves many gaps and questions. As for involvement in the official Aten religion and the temples, officials presumably commissioned some of the temple statuary of the royal family or small-scale temple equipment at workshops distributed throughout one whole zone of the city. Some of the society at least also seems to have had particular access to certain parts of the temple: the Stela Emplacement area toward the back is one example already noted. Certain figured ostraka or carved single ears—known elsewhere as dedications asking for a god's attention to prayers—may likewise be offerings deposited at some locale in the temples . Moreover, the huge bakeries attached to the Great Aten Temple, along with the many hundreds of offering tables in the temple, point to wide distributions of food, and these could be tied to broad accommodation within areas of the temple enclosure, possibly in connection with the festivals of the Aten promised on the boundary stelae. In their homes, officials might exhibit devotion to the royal family as the children of the Aten, sometimes constructing small chapels in gardens alongside their houses for their own or perhaps neighborhood use. And at least one structure located in the city's bureaucratic and military district was a sort of neighborhood shrine for a cult of the king. From the perspective of the small finds attached to houses and burials of the wider populace, there is very little overt evidence of attention to the new god, although such attention might not be well manifested in such finds for a variety of reasons. What is clear is that there was no absolute prohibition on other gods: material remains testify to continued interest in household gods like Bes and Taweret, protector deities like Shed and Isis, and belief in the efficacious magic of female or cobra figurines. The practice of honoring and invocation of important ancestors and probably other figures in the community through statues or stelae in household shrines or elsewhere seems to have pervaded society, and points to a better understanding of the phenomenon usually termed "ancestor worship". \^/

“Recent excavations have revealed the long-unknown cemeteries of the general populace. The royal and elite tombs have long been known: the royal tomb for Akhenaten along with other partly finished tombs lay in the Royal Wadi through the cliffs to the east of the city and probably held the king's body along with a number of his daughters and his mother, but these interments were removed; two groups of fine tombs for a number of the great officials lined the cliffs to the east of the city, although most of the owners were not actually buried there before habitation at the site was ended. In contrast, the recently excavated South Tombs Cemetery of the general populace shows ample evidence of use, probably holding about 3,000 individuals. A few of these individuals had coffins or stela or a piece of jewelry; most were simply wrapped, apparently not mummified, in a mat of rushes which served as a sort of coffin and accompanied by a few pots. While there was certainly no mention of traditional funerary religion involving Osiris in the royal or elite tombs, there was some variability in the South Tombs Cemetery: one burial had a coffin apparently representing the Sons of Horus. The remains present many points of interest, but perhaps most surprising is the evidence of duress and poor diet well beyond that known for other typical New Kingdom populations. The profile of the population in terms of age at death also indicates to researchers that an as yet unidentified epidemic scoured the population. Other cemeteries have been identified, and more excavation is anticipated.” \^/

Urban-Village Manufacturing Centers in Amarna

On archaeological finds in Amarna, Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “Like most settlement sites, industry leaves a particularly strong signature in the archaeological record of Amarna in the form of manufacturing installations, tools, and by-products. The site has contributed significantly to the study of the technological and social aspects of such industries as glassmaking, faience production, metalwork, pottery production, textile manufacture, basketry, and bread-making, and has been one of the hubs of experimental archaeology in Egypt.” Most of the places can be classified as “small-scale domestic production, courtyard establishments or formal institutional workshops” [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

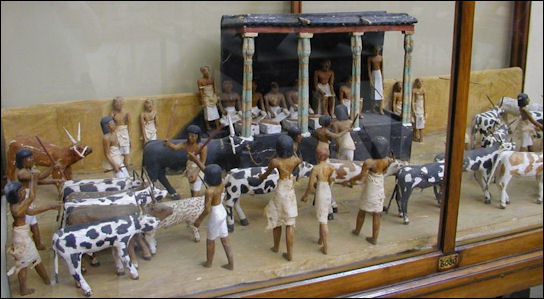

Marsha Hill of The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Village-like complexes produced statuary; stone, faience, and glass vessels, jewelry, or inlays; metal items, and the like. Usually several industries operated in the same complex, serving the furnishing and embellishment of the royal buildings and other needs; by providing for these workers, the official heading the complex must have had rights to the things produced, which he then provided toward the court undertakings. By contrast, a gridded, officially planned settlement, created probably to house workers on the royal tombs and known as the Workman's Village, lay out in the desert plain between the city and the eastern cliffs. Houses themselves, from the simplest to the most elaborate, favored a plan with an oblique entry, a central room with a low hearth for reception or gathering, pillared when possible, and bedrooms and workrooms further back. Second stories may have existed, but sleeping might also take place on the roof. Cooking and food preparation seem to have been done in courtyards. [Source: Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 2014, metmuseum.org \^/]

“As a beehive of building and production, the city provides many insights into ancient industry and technology, from construction, to manufacture of glass and faience, to statuary and textile production, to bread making. One revelation is the ubiquity of gypsum as a working material. Gypsum can be used as a stone, but its main use at Amarna was as a powdered material, which with various admixtures can produce anything from a hardening plaster, to an adhesive, to a concrete. Gypsum had long been employed in Egypt as a mortar, a ground for painting, and for its adhesive qualities, but at Amarna it was used to create great long foundation levels, to build up platforms, and in a few instances to form large concrete blocks that functioned like stone. It was used as a mortar for talatat and glue for inlay. It may even have been used to create a whole large stela surface in the newly discovered boundary stela H. And it was used to adhere the elements of the composite statuary created at Amarna, and apparently to construct some balustrades from a three-dimensional mosaic of pieces. The combination of flourishing and inventive composite methods with the ubiquitous use of gypsum-based adherents has the appearance of an acceleration of technological change that constitutes a kind of breakthrough, whether or not it had any validity when Amarna and Amarna systems were abandoned. \^/

Location and Layout of Armana

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “The principal remains lie on the east bank of the Nile, in a large bay that is bordered to the east by the limestone cliffs of the high desert. The ancient city probably included agricultural land and settlement on the west bank, but none of this is now visible beneath modern fields and buildings. The bay offers a low flat desert setting, the eastern cliffs forming a high and imposing boundary at their northern end, but lessening in height southwards. The cliff face is broken by several wadis, one of which, the Great Wadi, has a distinctive broad, rectangular profile that resembles the hieroglyph akhet (“horizon”). The shape of the wadi perhaps prompted Akhenaten to choose this particular stretch of land for his new city; at sunrise, the eastern cliffs in effect become a visual rendering of the name Akhetaten. It is curious that the Great Wadi has not revealed any 18th Dynasty remains, but the poor quality of the limestone here probably rendered it unsuitable for tomb cutting. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Thirteen Boundary Stelae have been identified to date on the east bank of the river and three on the west bank, the only trace of the ancient city yet found here. T he Stelae did not delineate a rigid boundary as such, and elements of the city, such as the tombs in the Royal Wadi, lay beyond the limits they defined. Inscriptions on the Boundary Stelae outline Akhenaten’s vision for the city, listing the buildings and monuments he intended to construct. Many of these can be identified within the broader archaeological record, being either directly identifiable on the ground; named in administrative inscriptions, such as jar labels and stamps on jar sealings; or represen ted in scenes within the rock-cut tombs of the city’s elite. The latter depictions, although often stylized, are an important aid for reconstructing the vertical appearance of the stone-built temples, shrines, and palace structures of Akhetaten, which were dismantled by Akhenaten’s successors and now survive only to foundation level. There are, however, institutions listed on the Boundary Stelae and in private tombs that have not yet been identified, among them the tomb of the Mnevis bull. Some of these were perhaps never constructed.

“Akhetaten was a long, narrow city that extended some 6 kilometers north-south along the river, and around 1 kilometers eastwards into the low desert. The city’s riverfront is probably long destroyed under the broad band of cultivation that occupies the riverbank, although there has been little attempt to check if anything survives here. The principal ruins of the city are now contained to the desert east of the cultivation. Akhetaten was largely a mud-brick city, although the most important ceremonial buildings were constructed of stone. The basic building stone was locally quarried limestone that was cut into smaller blocks (talatat) than the previous standard, probably to allow the rapid construction of the city. During the dismantling of the city after Akhenaten’s reign, most of the talatat were removed to other sites for reuse as construction materials, inc luding Assiut and Abydos, with many relocated over the river to the site of el-Ashmunein.

“Excavators divide Amarna into four main zones: the Central City, Main City, North Suburb, and North City. The Central City, located roughly opposite the Great and Royal Wadis, was the official hub of Akhetaten. It contained the two main temples (the Great Aten Temple and Small Aten Temple), two of the royal residences (the Great Palace and King’s House), and further ceremonial, administrative, military, industrial, and food-production complexes. The Main City was the largest residential zone, extending southwards from the Central City, the North Suburb its smaller counterpart to the north. At the far north end of the bay, the North City and its en virons contained housing areas and two additional royal residences (the North Palace and North Riverside Palace), and associated administrative/storage complexes. The North City palaces were connected to the Central City by a north-south roadway, now known as the Royal Road, which probably served, at least in part, as a ceremonial route for the royal family.

“The cliffs beyond, extending some 10 kilometers northwards into present-day Deir Abu Hinnis, contained the city’s main limestone quarries. Survey here has identified an extensive network of Amarna Period roadways that probably once linked the quarries to harbors and perhaps also quarry-workers’ settlements. Within the main bay, the low desert between the city and the eastern cliffs was largely free of settlement, apart from two workers’ villages, the Workmen’s Village and Stone Village. The desert to the south seems to have been a kind of cult zone, characterized by the presen ce of several isolated religious and ceremonial complexes: the so-called Maru Aten, and at the sites of Kom el-Nana, el-Mangara, and near el-Hawata. These are now largely lost under cultivation, but were probably dedicated especially to female members of t he royal family. Another ritual complex, the Desert Altars, lay in the northeast of the city . The low desert had a network of “roadways” that probably facilitated the movement of people and goods, but also the policing of the city’s eastern boundary, supported by guard-posts built at points around the cliffs . The low desert and eastern cliffs were also the location of Akhetaten’s cemeteries. Tombs for the royal family were cut in a long wadi now known as the Royal Wadi, and the main public burial grounds occurred in two clusters to the northeast and southeast of the city. Each combined decorated rock-cut tombs for the city’s elite set into the cliff face (the North Tombs and South Tombs) with simpler pit graves in the desert floor or within adjacent wadis. The two workers’ villages also had their own small cemeteries.”

Houses, Neighborhoods and Industrial Areas of Amarna

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “Houses at Amarna were built of mud-brick, with fittings in stone and wood. Although no two houses are identical, they show a preference for certain spaces and room arrangements, including a large focal room, often in the center of the building, from which other spaces opened. Most houses preserve a staircase, indicating at least the utilization of rooftops as activity areas, and probably often a second story proper. The elite expressed their status by building larger villas with external courtyards that included substantial mud-brick granaries, and sometimes incorporated ponds and shrines, the latter occasionally yielding fragments of sculpture depicting or naming the royal family. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The large expanses of housing exposed at Amarna have allowed for two fundamental observations on urban life and society here. The first is that smaller houses tend to cluster around the larger estates of the city’s officials and master-craftsmen. This arrangement suggests that the occupants of the former supplied goods and services to the owners of the larger residences, who were themselves presumably answerable to the state, in return for supplies such as grain. The second is that the variations in house size, likely to reflect in part differences in status, allow an opportunity to model the socio-economic profile of the city. When the ground-floor areas of Amarna houses are plotted on a graph according to their frequency, the resultant curve suggests a population that was fairly evenly graded in socio-economic terms, without sharp class distinctions . It is a model that has found support among housing and funerary data at other sites, including Thebes and possibly Tell el-Dabaa.

“Like most settlement sites, industry leaves a particularly strong signature in the archaeological record of Amarna in the form of manufacturing installations, tools, and by-products. The site has contributed significantly to the study of the technological and social aspects of such industries as glassmaking, faience production, metalwork, pottery production, textile manufacture, basketry, and bread-making, and has been one of the hubs of experimental archaeology in Egypt.” Most of the places can be classified as “small-scale domestic production, courtyard establishments or formal institutional workshops”

Main Area of Amarna

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “The principal features of Amarna are presented below as they appear roughly from north to south. North City, including the North Riverside Palace The North City is an area of settlement at the far north end of the Amarna bay, originally separated from the rest of Akhetaten to the south by a stretch of open desert. This northern zone of Amarna is one of the least well-published parts of the site. “The North City would originally have been dominated by the North Riverside Palace, most of which is now lost under cultivation. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The large residential zone that spreads southwards from the Central City is termed the Main City. The area is interrupted by a large wadi and is sometimes divided into two: Main City North and South, with a few buildings at the very south end of the site sometimes given the name South Suburb. The Main City and South Suburb combined cover about 2.5 kilometers of ground, north to south.

“The Main City was organized around at least three main north-south thoroughfares: East Road South, West Road South, and Main Road. Fieldwork has focused mostly upon the area east of the Main Road, which is occupied by fairly dense housing areas, generally arranged with smaller houses forming clusters around larger estates. Some of the buildings can be identified as workshops from the detritus left behind by their occupants, and there is a notable concentration of sculptors’ workshops through the northern end of the Main City, on the outskirts of the Central City.

“Apart from wells, there are few obvious public spaces or amenities among the Main City buildings. The buildings to the west of the Main Road remain mostly unexcavated and are now largely lost under cultivation, and it is not known to what extent they had the same residential character.”

Palaces and Royal Residence of of Amarna

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “The full extent of the North Riverside Palace “has never been mapped and all that is visible today is a part of the thick, buttressed eastern enclosure wall, although excavations in 1931-1932 exposed a small stretch of what may have been the palace wall proper. To the north of the palace, and perhaps once part of it, is a large terraced complex containing open courts and magazines known as the North Administrative Building. The land to the east of the palace is occupied by houses that include several very large, regularly laid out estates, and also areas of smaller housing units beyond, running up to the base of the cliffs. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“This is the best recorded of the Amarna palaces, having been excavated first in the early 1920s and recleared and restudied in the 1990s. The palace was built around two open courts separated by a pylon or possible Window of Appearance, the second court containing a large basin that probably housed a sunken garden. Opening off each courtyard was a series of smaller secondary courts containing altars, magazines, an animal courtyard, probable service areas, and a throne room. A feature of the site was the good preservation of its wall paintings when exposed in the 1920s

“The North Palace and North Riverside Palace are generally thought to have been the main residences for the royal family, the palaces in the Central City playing more ceremonial and administrative roles. The North Palace has often been assigne d to female members of the royal family, whose names appear prominently here, although Spence considers it more likely that royal women had chambers within the North and North Riverside Palaces rather than an entirely separate residence.

“To the south again is a walled complex now termed the King’s House that was connected to the Great Palace by a 9 meters wide mud-brick bridge running over the Royal Road. At the King’s House, the bridge descended into a tree-filled court that led to a columned hall with peripheral apartments, one of which contained a probable throne platform. The famous painted scene of the royal family relaxing on patterned cushions originates from this building; other painted scenes include that of foreign captives, perhaps connected with a Window of Appearance. The complex also contained, in its final form, a large set of storerooms.

“Extending beyond the King’s House to the east was a series of administrative buildings, roughly arranged into a block, among them the “Bureau of Correspondence of Pharaoh,” where most of the Amarna Letters were probably found, an d the “House of Life.” To their south is a set of uniformly laid out houses generally thought to have been occupied by administrators employed in the Central City. In the desert to the east lies a complex identified by the EES excavato rs as military/police quarters. Nearby were several further enclosures, among them a small shrine, the House of the King’s Statue, which has been suggested as a state-built public chapel, perhaps built for those who worked in the Central City.”

Temples and Desert Altars at Amarna

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “On the eastern side of the Royal Road lay the Great Aten Temple and Small Aten Temple. The former occupied an area of 800 x 300 m, much of it apparently left empty, contained by a mud-brick enclosure wall. A reexamination of the building began in 2012, confirming that it had two main construction phases. In its final phase, the enclosure contained at least two main buildings: a structure now termed the Long Temple (originally perhaps the Gem-pa-Aten ) towards the front, and the Sanctuary to the rear. The former contained at least six open-air courtyards occupied by several hundred offering tables. Tomb scenes suggest that three of the courts contained cultic focal points: a raised altar in one case, and offering tables in the other two. Along the front of the temple was a series of pedestals surrounded by white-plastered basins. Offering tables and pedestals surrounded by basins were also a feature of an earlier iteration of the temple here, la rgely buried beneath the later structure. Massive fields of mud-brick offering tables that flank the Long Temple to its north and south have also now been shown to belong to the first phase of the temple. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The Sanctuary comprised a rectangular stone building divided in two parts, each open to the sky and filled with offering tables, although recent fieldwork has shown that this area initially featured a grove of trees and a mud-brick altar or pedestal. Three further features occupied the ground in front of the Sanctuary. A building comprising four suites of rooms with lustration slabs was built across the northern enclosure wall, perhaps as a purification s pace for people entering the temple (although identified as the “hall of foreign tribute” by the EES excavators). To the south there was originally an altar or similar construction that supported a stela, pieces of which have been recovered during excavation, and probably a statue of the king, as shown in tomb scenes. To the west of the stela lay a butchery yard, which presumably facilitated the supply of meat offerings to the Aten. Immediately south of the Great Aten Temple is a series of buildings that p robably also served the temple cult, especially the preparation of food offerings. These comprise: the house of the high priest Panehesy; a building containing several columned halls with stone-lined floors and lower walls, troughs, and ovens, perhaps connected with meat processing; a bakery formed of chambers often containing ovens, near which lie large dumps of bread mold fragments; and a set of storerooms and associated buildings.

“The Small Aten Temple, or Hut Aten , lay immediately south of the King’s House, occupying a walled enclosure of 191 x 111 meters that was divided into three courts. The first court contained a field of offering tables flanking a large mud-brick platform of uncertain purpose. The second court contained a house-like building with small dais that was perhaps a throne base; there is space for other structures here that might have been entirely destroyed. The final court contained the stone Sanctuary, very similar in layout to that at the Great Aten Temple and likewise containing many offering tables. The Sanctuary was flanked by trees, and there were several small brick buildings in the ground around it. South of the Small Aten Temple was another set of chambered structures recalling those beside the Great Aten Temple and which may likewise have served as bakeries, although there is also evidence that faience and glass items were produced here.

“The Desert Altars lie on the desert floor not far from the North Tombs. The complex had two main enclosures. The first, in its final form, contained three separate foundations arranged in a line within a court formed simply by clearing the desert of stones. The southernmost supported a colonnaded building, the central construction formed a large altar flanked by two smaller altars, and the northernmost foundation comprised a mud-brick altar approached by ramps on four sides. The second enclosure was originally defined by a mud-brick wall and contained at least one stone-built chapel. It has been suggested that the complex was associated with private funerary cults ; Kemp has also noted similarities between the arrangements of the shrines here and buildings shown in the “reception of foreign tribute” scenes in the nearby tombs of Huya and Meryra II.

“Based on excavated remains, and tomb scenes, it is possible to reconstruct the general ground plan of the complex. The western part of the palace was dominated by stone-built state apartments, with a large courtyard containing statues of the royal family leading to a series of courts and halls, and a possible Window of Appearance. The eastern part was built instead largely of mud-brick, comprising a strip of buildings that included magazines; an area identified by the EES excavators as the “harem quarter,” featuring a sunken garden and painted pavements; and a set of houses and storerooms that probably served as staffing quarters. Late in the Amarna Period, a large pillared or columned hall was added to the southern end of the palace, with stamped bricks bea ring the cartouche of Ankh-kheperura lending it the name Smenkhkare Hall (or Coronation Hall). This area is badly destroyed.”

Boundary Stelae of Amarna

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “The Boundary Stelae take the form of tablets carved directly into the limest one bedrock and reaching up to 8 meters in height. Flinders Petrie was the first to methodologically survey these monuments, numbering them alphabetically, but leaving gaps in the sequence to allow for new discoveries, o f which there were none until 2006 when surveyor Helen Fenwick noted a new stela (H) in the eastern cliffs. The stelae have been published in two monographs, with accompanying black-and-white photographs and partial copies of their inscriptions. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Sixteen stelae are known, three on the west bank of the river and the remainder on the east bank. Their purpose was partly to define the limits of the ancient city, and partly to allow Akhenaten to outline his vision for Akhetaten. They are topped with scenes of the royal family worshipping the Aten, and most had statues of the royal family cut out of the rock at their base. The bulk of each tablet, however, is occupied with inscriptions in the form of “proclamations,” including lists of institutio ns the king intended to found. An “earlier proclamation,” inscribed in Year 5, is known from three of the stelae, and the “later proclamation” of Year 6 occurs on 11 examples.

“The earlier proclamation, now less well preserved, was the more detailed of the two, concerned especially with the proper maintenance of the cult of the Aten, outlining festivals to be undertaken for the god, and endowments for the cult. Among the most notable and often-cited statements within the proclamations are the king’s claims t hat Akhetaten was previously unoccupied, and his vow to repair the stelae in the event they are damaged.”

rock tombs of Armana map from 1903

Main Tomb Sites at Amarna

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “The Royal Tomb, one of the foundations listed on the Boundary Stelae, was cut into the limestone bedrock deep in the Royal Wadi in the eastern cliffs, recalling the Valley of the Kings in Luxor. Although unfinished, the tomb was used for the buri als of Akhenaten, princess Meketaten, probably Queen Tiy, and another individual, perhaps Nefertiti. At the end of the Amarna Period the contents of the tomb were partly relocated to Thebes. The tomb was badly looted shortly after its discovery in the late nineteenth century and has suffered subsequently from vandalism and flooding. The walls nonetheless retain important scenes, including those alluding to the death of princess Meketaten, perhaps in childbirth. The Royal Wadi also conta ins three additional unfinished tombs and another chamber that is either a store for embalming materials or a further tomb.[Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

The North Tombs are a set of elite tombs cut into the cliffs of the high desert towards the northern end of the Amarna bay. There are six principal tombs, numbered 1-6, which belonged to high officials in Akhenaten’s court. Although none was fully completed, these preserve decoration that is notable for representing the city’s monuments, the prominence given to the king and royal family, and the presence of copies of the Hymns to the Aten . There are also several other undecorated tombs. The tombs were reoccupied by a Coptic community in around the sixth to seventh centuries CE and the tomb of Panehesy (no. 6) converted into a church at this time.

“Adjacent to the North Tombs are a number of non-elite burial grounds. The largest, which probably includes several thousand interments, occupies a broad wadi between North Tombs 2 and 3. The graves here take the form of simple pits cut into the sand, containing one or more individuals wrapped usually in textile and mats. There is also a smaller cemetery at the base of t he cliffs adjacent to the tomb of Panehesy (no. 6) and another in the low desert some 700 meters to the west of this, both as yet unexcavated.

“South Tombs and South Tombs Cemetery, a second group of rock-cut tombs belonging to the city’s elite, is situated at the cliff-face southeast of the Main City. There are 19 numbered tombs (nos. 7-25) and several other unnumbered chambers. The tombs are in a less finished state and are smaller tha n the North Tombs. Large quantities of pottery dating to Dynasties 25 and 30 litter the ground nearby, suggesting the tombs were reused in the Late Period.

“The rock-cut tombs are again only the elite component of a much larger cemetery that occupies a 400 meters long wadi between Tombs 24 and 25. Fieldwork here from 2005 to 2013 revealed a densely packed cemetery containing the graves of several thousand people, those of adults, children, and infants intermingled. The deceased were usually wrapped in textile and a mat of palm midrib or tamarisk and placed singly in a pit in the sand. Less often, they were buried in coff ins made of wood, pottery, or mud. The decorated coffins include examples with traditional funerary deities, and in a new style in which human offering bearers replace the latter. Most graves seem to have been marked by a simple stone cairn, and in some ca ses a small pyramidion or pointed stela showing a figure of the deceased . Fragments of pottery vessels that presumably often contained or symbolized offerings of food and drink were common. Other grave goods were rare, but included such items as mirrors, kohl tubes, stone and faience vessels, tweezers, and jewelry such as scarabs and amuletic beads. The study of the human remains showed an inverse mortality curve, ages at death highest between 7 and 35 years, with the peak between 15 and 24 years.”

Worker’s Village of Amarna

Amarna

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “The village is one of few housing areas at Amarna to have been formally planned: it is laid out with rows of 73 equally sized house plots, and one larger house, all surrounded by a perimeter wall around 80 centimeters thick with two entranceways. Apart from the larger house, thought to belong to an overseer, the village houses exhibit at ground-floor level a tripartite plan not generally found in the riverside suburbs, with a staircase leading to a roof or further s tory/s above . Perhaps quite soon after the village was founded, its occupants modified and added to their houses and settled the land outside the village walls, constructing chapels, tombs, animal pens, and garden plots. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The latter reflect the efforts of the villagers themselves to sustain their community, but the isolated location of the site, and lack of a well, also made it dependent on supplies from outside. An area of jar stands known as the Zir Area on the route into the village seems to represent the standing stock of water for the village, supplied by deliveries from the riverside city, the route of which is still marked by a spread of broken pottery vessels (Site X2). Near the end of the sherd trail there is a small building (Site X1), which may be a checkpoint connected with the importation of commodities.

“Given its location and similarity to the tomb workers’ village at Deir el-Medina, the Workmen’s Village is thought to have housed workers, and their families, who cut and decorated the rock-cut tombs, including those in the Royal Wadi. This identification is supported by the discovery at the site of a statue base mentioning a “Servant in the Place,” recalling the name “Place of Truth ” used by the tomb-cutters at Deir el-Medina.

“The internal history of the village, however, is not easy to reconstruct. At some stage an extension was added to the walled settlement, possibly to accommodate a growing workforce to help complete the royal tombs. It has also been suggested that, perhaps late in its occupation, the site housed a policing unit. Excavations have produced a relatively high proportion of jar labels and faience jewelry from the last years of the reign of Akhenaten and those of his successors, suggesting a burgeoning of activity at this time, but without ruling out earli er occupation. The discovery of a 19 th Dynasty coffin beside the Main Chapel indicates that the village site was still known of later in the New Kingdom.”

Stone Village at Amarna

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “The Stone Village lies on the north face of the same plateau that shelters the Workmen’s Village. Like the Workmen’s Village, the site had a central occupation area (the Main Site), encompassing around half of the area of the walled settlement at the Workmen’s Village. Excavations here revealed remains of both roofed structures and external spaces that were in part likely residential, but were not laid out in the same neat arrangement of houses as the Workmen’s Village. The excavated buildings were made almost entirely from desert clay and limestone boulders, with little sign of the alluvial bricks that were used to lay out the Workmen’s Village houses and perimeter wall. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“While the Main Site was surrounded at least in part by an enclosure wall, this was around half the thickness of that at the Workmen’s Village and seems not to have been part of the original layout. And the extramural area of the site is also far less developed than that of the Workmen’s Village, with no obvious sign of chapels, garden plots, or animal pens, although there are marl quarries and a small cemetery. Two simple stone constructions on top of the plateau (Structures I and II) were perhaps connected with the supplying and/or policing of the site, while a smaller stone emplacement to the north (Structure III) was possibly a guard post.

“The purpose of the Stone Village is difficult to pinpoint, but it seems likely to also have housed workers involved in tomb construction. Large numbers of chips of basalt have been found at the site (and likewise at the Workmen’s Village), perhaps for making large pounders of the type used for stone extraction in the Royal Wadi. Given the limited sign of state input in laying out the site, and its simplicity in comparison to the Workmen’s Vil lage, it may be that the workers here were less skilled or of lesser social standing than those at the latter. The possibility that the site had secondary functions —such as supplying desert-based workforces —also remains.”

Kom el-Nana Cult Complex at Amerna

main city of Amarna

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “The ruins at Kom el-Nana are the best preserved and studied of the peripheral cult complexes, excavated by the Egyptian Antiquities Organization. Located southeast of the Main City, the site comprises a large enclosure some 228 x 213 m, divided into a northern and southern court. The latter was dominated by a podium (the “central platform”) accessed by ramps on at least its north and south sides, and supporting rooms including a columned hall with stepped dais, possibly the location of one or more Windows of Appearance. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“South of the central platform was a long narrow processional building (the “southern pavilion”) containing columned spaces and two open courts with sunken gardens, and to its north the so-called South Shrine, which seems to have included a set of chambers on the east and a columned portico to the west. Badly demolished at the end of the Amarna Period, thousands of pieces of s mashed up limestone and sandstone blocks were found here. Inscriptions on some of these identify the site as the location of a Sunshade of Ra, probably dedicated to Nefertiti, whose image also appears prominently in reliefs; other inscriptions give the nam e rwd anxw jtn , an institution mentioned in the tomb of the official Aye in connection with the provision of mortuary offerings. The southern court also contained a series of tripartite houses and garden plots.

“The northern court housed a second stone shrine, the North Shrine, of which only a small part has been uncovered, along with a bakery and brewery complex. Part of the northern enclosure was overbuilt by a monastery in around the fifth and sixth centuries CE that included a s mall church decorated with wall paintings. The excavations of the monastery are published only as preliminary reports, but studies of its ceramics and glassware and archaeobotany have appeared.”

Maru Aten, a Ritual Complex at Amarna

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “The Maru Aten was a ritual complex, incorporating a Sunshade of Ra dedicated to Meritaten, at the far south end of the Amarna plain. The site is known for having been elaborately decorated, including with painted pavements, but is now lost under cultivation. The site comprised two enclosures, a northern one, built first, and southern one. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The northern court was dominated by a large shallow pond surrounded by trees and garden plots, with a viewing platform and causeway built at one end. At the other end was a stone shrine adjacent to an artificial island on which was a probable solar altar flanked perhaps by two courts. The northern enclosure also contained T-shaped basins, probable houses, and other buildings of uncertain purpose. The southern enclosure likew ise had a probable central pool (not excavated) and a building at either end, one a mud-brick ceremonial structure, perhaps for use by the royal family, and the other a stone building of uncertain function.

“The “Lepsius Building” and El-Mangara A few hun dred meters southwest of the Maru Aten there likely stood another stone-built cult or ceremonial complex, noted briefly by Lepsius in 1843, while at the site of el-Mangara, about 1700 meters southeast of Kom el-Nana, evidence was also collected in the 1960s for a stone-built complex, in the form of largely intact decorated blocks, mud-brick, and Amarna Period sherds. Both sites are now lost under cultivation.”

Roads at Amarna

bathroom at a house in Amarna

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “The city incorporated several thoroughfares, generally running north-south, the most important of which is now known as the Royal Road. It linked the palaces at the north of the Amarna bay to the Central City and then continued southwards, with a slight change of angle, through the Main City. It is just possible that part of its northern span was raised on an embankment, a mud-brick structure north of the North Palace, cleared briefly in 1925, perhaps serving as an access ramp. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The line of the road from the North Palace through the Central City, if projected southwards, also passes directly by the Kom el-Nana complex near the southern end of the site, suggesting that it was used in laying out the city. Thereafter, the Royal Road probably remained an important stage for the public display of the royal family as they moved between the city’s palaces and temples.

The low desert to the east of the city was crisscrossed by a network of roadways : linear stretches of ground, c. 1.5-11 meters in width, from which large stones have been cleared and left in ridges along the road edges. The most complete survey of the road network is that of Helen Fenwick; its full publication is pending. The roads probably served variously as transport alleys, patrol routes, and in some cases as boundaries, and suggest fairly tight regulation of the eastern boundary of the city. Particularly well-preserved circuits survive around the Workmen’s Village and Stone Village. The roadways are among the most vulnerable elements of Amarna’s archaeological landscape, although protected in part by their isolated locations.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024