Home | Category: New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut)

AMENHOTEP III

Amenhotep III Colossal Amenhotep III (1390-1353 B.C. ) ruled for 38 years during a period of relative peace and prosperity . He built the Colossi of Memnon and the Mortuary of Amenhotep III and spent a lot of time hunting. One commemorative scarab said he killed “102 fearful lions” during the first 11 years of his rule. Amenhotep III was the grandfather of King Tutankhamun. [Source: Andrew Lawler, Smithsonian magazine, November 2007]

Amenhotep III came to the throne as a teenager after the death of his warrior father Thutmose IV. He chose to spend much of his time in Thebes (Luxor) rather than Memphis, where most of the other pharaohs spent their time . After quelling an uprising in Nubia he chopped off the arms of 312 enemies but was more restrained and diplomatic during most of his rule. His principal wife Tiye by various accounts was a Nubian, a commoner or from a noble Egyptian family. His harem included women from rival powers such as Babylon and Mitanni. Queen Tiye (1390-1349) was deeply involved in politics. She abdicated when the king died and made a living as a goddess.

Amenhotep III controlled a rich empire stretching 1,200 miles from the Euphrates in the north to the Fourth Cataract of the Nile in the south. Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic, “Along with his powerful queen Tiye, he worshipped the gods of his ancestors, above all Amun, while his people prosper and vast wealth flows into the royal coffers from Egypt's foreign holdings.”[Source: Zahi Hawass, National Geographic, September 2010]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Amenhotep Iii: Egypt's Radiant Pharaoh” by Arielle P. Kozloff (2012) Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of a Pharaoh: The Intimate Life of Amenhotep III” by Joann Fletcher (2000) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun, Nefertiti, Akhenaten and Amenhotep III - Pharaohs of the Solar Dynasty: The 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, an Era of Intrigue, Murder, and Revolutionary Religious Change” by Claudio Bocchia (2024) Amazon.com;

“Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen” by Rita E. Freed and Yvonne J. Markowitz (1999) Amazon.com;

“Studies on the Palace of Amenhotep III at Malqata” by Peter Lacovara, Franck Monnier, John Shearman (2023) Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom" by Joyce Tyldesley (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume III: From the Hyksos to the Late Second Millennium BC” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt: A Captivating Guide” Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

"The New Kingdom" by Wilbur Smith, Novel (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

Amenhotep III's Achievements

Dr Kate Spence of Cambridge University wrote for the BBC: The reign of Amenhotep III was “long and prosperous with international diplomacy largely replacing the relentless military campaigning of his predecessors. The reign culminated in a series of magnificent jubilee pageants celebrated in Thebes (modern Luxor), the religious capital of Egypt at the time and home to the state god Amun-Re.” [Source: Dr Kate Spence, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Amenhotep III presided over Egypt during an unprecedented time that is often referred to as the Egyptian Golden Age. The pharaoh was responsible for commissioning some of the grandest monuments Egypt had ever seen, and he ruled during a period when Egyptian artists were extremely prolific — more statues of Amenhotep III survive today than of any other Egyptian pharaoh. The pharaoh's extraordinary building campaign spurred urban growth in his capital of Thebes. He commissioned monumental structures such as his mortuary temple, the scale of which is only just beginning to be understood as a result of archaeological research over the past two decades. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

Amenhotep III achieved some military success by launching campaigns into Nubia early in his reign and benefited greatly from the martial exploits of his great-grandfather Thutmose III. He inherited a territory that stretched across more than 1,000 miles from modern Sudan to Syria. The gold that poured into his coffers from this great empire and the relative peace the country enjoyed enabled Amenhotep III to employ an army of expert architects, builders, painters, sculptors, and artisans who expressed the glory of his age in art and architecture.

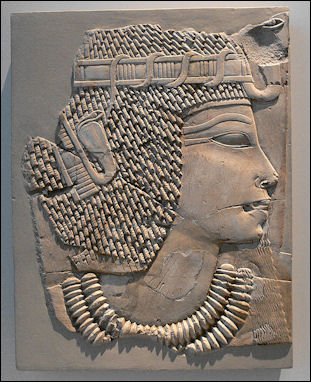

Quartzite head of Amenhotep III

He commissioned the construction of and sponsored the restoration of temples and monuments up and down the Nile and transformed the capital of Thebes. On the east bank, he carried out extensive additions and renovations to the Karnak and Luxor Temples, as well as to smaller religious complexes. On the west bank, the pharaoh built himself a vast sprawling estate at the site of Malqata. This lavish complex was the largest residence in Egypt and included an artificial harbor measuring one and a half miles long.

Amenhotep III went through great lengths to maintain peace. He wrote conciliatory letters to Mesopotamian leaders and established trade relations throughout the Mediterranean, Western Asia and Africa. The main resource that Egypt had to trade was gold. An envious Assyrian king wrote, “Gold in your country is dirt: one simply gathers it up.” With the wealth that his kingdom accumulated Amenhotep III built temples from the Nile Delta to Nubia 1,200 kilometers to the south. He expanded the temples at Karnak and Luxor and built a great mortuary temple for himself. Art and sculpture with an eye for detail and craft were produced.

Some have said that Amenhotep III was the source of Akhenaten’s monotheism. He named his royal boat and a Thebean palace Aten (the word that Akhenaten would use for his single god) and in some inscription mentioned Aten and no other gods. However Amenhotep III principal object of worship was Amun-Ra a combination of the main Thebean god and the sun god. He claimed that Amun disguised as his father entered Amenhotep III’s mother’s bedchamber before his birth and thus was his father, asserting that he was the most divine Pharaoh that had ever existed.

Amenhotep III’s Reign

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “Amenhotep III was the great grandson of Thutmose III. He reigned for almost forty years at a time when Egypt was at the peak of her glory. He lived a life of pleasure, building huge temples and statues. He was incredibly rich and his palace at Thebes was the most opulent of the ancient world. With stable international trade and a plentiful supply of gold from the mines, the economy of Egypt was booming. This great wealth led to an outpouring of artistic talent and Amenhotep was the driving force behind this activity. Much credit must also go to the king’s scribe, overseer, and architect, Amenhotep, son of Hapu, who was so highly thought of by the king that he was rewarded with his own mortuary temple. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

“In the early years of his reign, Amenhotep was a vigorous young man who enjoyed sport and hunting. In his fifth year as king, he led an expedition to Nubia to put down a rebellion, but there was no need for military activity for the remainder of his reign. Amenhotep favored peaceful pursuits over war—although he wasn’t averse to adopting grandiose names, at one point describing himself as “Great of strength who smites the Asiatics.” ^^^

“As he aged, Amenhotep grew fat and suffered ill health. His mummy shows that he endured painful dental problems. There is even a record of one of his allies, king Tushratta of Mitanni, sending him a statue of the goddess Ishtar for its healing properties. Amenhotep began restricting the power of the priests of Amun by recognizing other cults. One of these was a special form of the god Ra known as the Aten. It was this deity which Amenhotep’s son, Akhenaton, was to promote as the one and only true god, causing trouble within Egyptian society over the next generation. Amenhotep’s greatest legacy was his high standard of artistic and architectural achievement. This sophisticated and refined taste in art permeated Egyptian society and is manifest in the tombs of high officials such as Ramose and Khaemhet. He set the stage for Akhenaton’s unique style and left some of the finest monuments in Egypt. Amenhotep truly deserves the title “the Magnificent.”“ ^^^

Amenhotep III’s Rule

Amenhotep III relief Amenhotep III ruled Egypt from 1391 to 1353 B.C. He ruled an Egypt that stretched from the Nile Delta all the way southward to what is now known as the Sudan. Except for a brief and triumphant campaign in Nubia in his teens, when he was said to have come down on his enemies like a falcon upon its prey, he never went to war, nor saw any reason to do so. In governmental terms, his situation was ideal. His was an Egypt in which harvests were superabundant and nobody ever went hungry. Virtually limitless supplies of gold from Nubia relieved him of all financial problems. The word "deficit" was never heard. Harbor patrols and construction work were the main activities of his large standing army.

Dr Kate Spence of Cambridge University wrote for the BBC: The reign of Amenhotep III was “long and prosperous with international diplomacy largely replacing the relentless military campaigning of his predecessors. The reign culminated in a series of magnificent jubilee pageants celebrated in Thebes (modern Luxor), the religious capital of Egypt at the time and home to the state god Amun-Re.” [Source: Dr Kate Spence, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Foreign policy was a matter of unhurrying diplomacy and well-crafted matrimonial moves. Amenhotep III knew how to delegate, and he was surrounded by brilliant, dedicated and incorruptible professionals who gave the notion of bureaucracy a shine that it has long since lost. Thor, the god of writing, was held in honor at his court, the activities of which are documented to a quite exceptional degree.

In his 30's, Amenhotep III staged a series of ritual banquets on a more than Rabelaisian scale. (To gnaw at a bone as long as one's arm was not thought to be anything unusual.) But the life style that we find recorded in the Cleveland show is primarily one in which hard work, probity and inspired statecraft go hand in hand with an eye to the universality of the king who was also a god.

Amenhotep III and the Arts

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “Amenhotep’s patronage of the arts set new standards of quality and realism in representation. His building works can be found all over Egypt. Many of the finest statues in Egyptian art, attributed to Ramses II, were actually made by Amenhotep III. (Ramses II simply removed Amenhotep’s name and replaced it with his own.) One of Amenhotep’s greatest surviving achievements is the Temple of Luxor on the east bank of the river. Unfortunately, his mortuary temple, the largest of its kind ever built, was destroyed when Ramses II used it as a quarry for his own temple. Only the two colossal statues that stood at the entrance survive. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

In the early 1990s the the Cleveland Museum of Art hosted an exhibition called "Egypt's Dazzling Sun: Amenhotep III and His World." On the show John, “The show cannot of course include the enormous building projects on which Amenhotep III gave so much of his time. (For that matter, nobody today can see them, because his immediate successors took a delight in destroying or disfiguring them.) But we remember portraits in stone of human beings of every kind and station. We also remember lions, rams, sphinxes and scribes. With them come reliefs, household objects and spectacular pieces of jewelry. This was a moment in Egyptian history when all went well. [Source: John Russell, New York Times, July 12, 1992]

His interests and his character would seem to have been formed by the time that he came to the throne as a mere boy. For instance, there is in the present show a sunken relief that shows him, at around 12 or 14, in the act of opening new limestone quarries at Tura, not far from Cairo. It was in Tura that the facing stones for the great pyramids in Giza and Sakkara had been quarried. Amenhotep III in later life was to be a great connoisseur of Egyptian stones, hard and soft, in all their variety. Nor did anyone ever put those stones to more eloquent use. So there is something as apt as it is touching about the gesture of the slender and limber boy king as he swings his left arm across his body to sprinkle the ritual incense.

Later statues of the king were sometimes as much as 25 feet high. A colossal head of Amenhotep III, more than seven feet high, sits in the museum in Luxor. Are we awed by the head? Of course we are, and not least by the gleaming actuality with which a likeness of living flesh has been wrested from one of the hardest and least amenable of all stones. To that end, a whole team of master craftsmen contributed.

Viewers attuned to the gaudy attractions of the Tutankhamen tomb may find the art produced under Amenhotep III lacking in panache. Others, bemused by the brutish and dictatorial bearing of the art and the architecture that they associate with Ramses II, who ruled roughly a century later, may find too much tenderness in the art of Amenhotep III.

Amenhotep III’s Family and Private Life

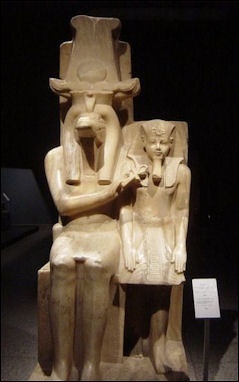

Amenhotep III and Sobek, god of the Nile

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “Indulging himself in all the pleasures, extravagances, and luxuries of life were his priorities. He had a large harem that included foreign princesses, though the great love of his life was his queen, Tiy, whom he had married before becoming king. She was a commoner, which was unusual for a chief wife. While most royal marriages were politically motivated, Amenhotep’s marriage to Tiy seems to have been motivated by genuine feeling. He made her a lake 3,600 cubits long by 600 cubits wide (about a one mile 1.6Km in length) in her town of T’aru. He then held a festival on the lake, during which he and Tiy sailed a boat called the Disk of Beauties. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

“Tiy gave birth to six children: four daughters and two sons. The eldest boy, Thutmose, became a priest and is thought to have begun the tradition of burying the mummified Apis bull, which was believed to be the incarnation of the god Ptah. Unfortunately, Prince Thutmose died, and his brother, the future Akhenaton, ascended the throne.” ^^^

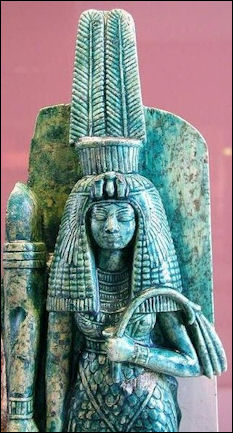

Russell wrote in the New York Times that Amenhotep III’s art “was an art that excelled as much in intimacy as in the grand public gesture. His favorite wife, Queen Tiy, was a paragon of good looks who came from more or less nowhere, in social terms, but was in every other way her husband's equal. In time, she ranked with him not only as a ruler but also as a goddess, and her husband built a temple to her in northern Sudan. [Source: John Russell, New York Times, July 12, 1992]

The portraits of Queen Tiy...like the portraits of her daughters, have an immediacy and a freedom from formula that seem to have disconcerted earlier generations and contributed to the fact that the art of Amenhotep III and his world has not always been highly esteemed. As recently as 1956, two German art historians castigated Amenhotep III for what they called "his emphasis on his private life, unparalleled in earlier times." In their view, he was "diverted from his highest political duty" by "an excessive desire to build and an ever-increasing search to free his personality."

For this critic, at any rate, few rulers have been more faithful to their "highest political duty" than Amenhotep III. As for the emphasis on his private life, it is one of the most endearing features of the Cleveland show — and not least in the reconstruction of the royal bedroom, with its wealth of household objects and apparatus of discreet luxury.

It is the virtue of the period (from our point of view) that it wrought very small marvels as well as huge ones. The perfume bottles, the spoons, the combs, the tubes for eye paint, the matrimonial ointment flask (inscribed to both spouses, by name), the ear studs, the bracelets, the cabochon finger ring, the three-handled perfume jar, the painted wooden box with its gabled lid — all combine as much to amuse as to seduce.

There are also one-of-a-kind pieces like the wonderfully sprightly little figure of a European spoonbill that came from the royal palace in Thebes. To the connoisseur of miniaturization I commend above all the bright yellow ceramic figure of a swimming duck that measures no more than a fraction of an inch in any direction and is yet most vividly alive. But it is in the portrayal of the human figure — whether prince or princess, civil servant or seated scribe — that this art is consistently sublime. It is not as the victims of established formula that these people confront us, but as free-spirited individuals.

Dazzling Aten

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology Magazine: The picture of Amenhotep III’s “golden” Thebes has only been enhanced by the recent chance discovery of a previously unknown city built during his reign, now buried amid the monuments of the west bank. Some archaeologists consider this city one of the most important discoveries of the past century in Egypt. The remnants of both the temple and the city now stand as potent reminders of an era of peace and prosperity that preceded one of the most tumultuous periods in Egyptian history. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

Queen Tiye,

wife of Amenhotep In 2020 Egyptologist Zahi Hawass began searching for Tutankhamun’s mortuary temple just north of Medinet Habu in the Luxor area, near the site of the mortuary temples of Ay (r. ca. 1327–1323 B.C.) and Horemheb (r. ca. 1323–1295 B.C.), two of Tutankhamun’s successors. As the excavations unfolded, Hawass’ team failed to turn up definitive evidence of Tutankhamun’s mortuary temple, but instead found something unexpected.

As they began removing layers of debris amassed over thousands of years, they gradually exposed a network of well-preserved mudbrick walls that seemed to extend in every direction. Eventually they revealed streets, houses, storerooms, artists’ workshops, and industrial spaces, along with at least 1,000 artifacts. Some of the walls still stood to a height of 12 feet. Yet the settlement was an enigma as no ancient records mention it. Scholars wondered when it was founded, who built it, and what it was called. The answers became apparent when Hawass uncovered a series of wine jars. Mudbrick seals used to close the vessels were inscribed with hieroglyphs that spelled out the name of the city — Tehn Aten, or “Dazzling” Aten, a name that unequivocally pointed to one ruler: Tutankhamun’s grandfather, the pharaoh Amenhotep III. “I originally called it the Golden City or the Lost City because it dates to the reign of Amenhotep III, which was the Golden Age of ancient Egypt, and because nothing was known about it,” Hawass says.

During the New Kingdom — with one brief interlude — Amun (or Amun-Ra), the supreme god, was worshipped as first among the Egyptian gods. Over time, however, Amenhotep III increasingly began to portray himself as a sun god and promoted a new aspect of the deity known as Aten to prominence. Aten was the disk of the sun, the giver of light and life, and Amenhotep III adopted the epithet “the dazzling Aten” for himself as well.

Dazzling Aten’s Residential Area

The logistics of supplying and maintaining a complex of this size would have been extremely complicated and involved thousands of people. It would have required its own support city, one that, in fact, eventually rose just beyond its gates — the city of Dazzling Aten. Hawass’ ongoing excavations have thus far uncovered parts of three separate districts surrounded by serpentine walls. These districts were likely part of an even more extensive settlement — which may have reached the gates of Amenhotep III’s Malqata Palace to the southwest and Deir el-Medina to the north, where the workers who built the tombs in the Valley of the Kings lived. For Hawass, this new discovery dispels the misconception that, unlike other contemporaneous cultures, ancient Egypt lacked major metropolises. “It is the largest ancient Egyptian settlement ever found,” he says. “Egypt was not a civilization without cities.”

Dazzling Aten had residential and administrative quarters, where people lived and royal officers carried out official business, but perhaps its most telling characteristic was its industrial space. There were numerous workshops producing faience jewelry, clothes, sandals, leather goods, food, and even toys for children living in the Malqata Palace. “The city really existed to provide the palace and the temples with what they needed,” Hawass says. Most recently, a large lake was discovered north of the city that provided fresh water not only for drinking and cooking, but also for the city’s booming mudbrick industry, which manufactured the materials for Amenhotep III’s building projects.

There is even evidence that sculptors working and living in Dazzling Aten created the hundreds of statues that once decorated the great peristyle court of Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple. “We have uncovered a workshop where the statues of Sekhmet were crafted,” Hawass says. “I believe they were all built in this city.” It’s also likely, he says, that some of the extra-ordinary objects that would be entombed with Tutankhamun just a few decades later were originally crafted by Dazzling Aten’s artisans. “It was the Golden Age of the New Kingdom,” says Hawass, “but if anyone closes their eyes to imagine the magnificence of this area with the palaces and the city of Dazzling Aten and the funerary temple, it goes beyond that, especially in the architecture and statuary.”

Colossi of Memnon

Colossi of Memnon (next to the road between the ferry and the ticket office) consists of two seated statues of Amenhotep III and are named after Memnon, a Greek hero whose mother, the Dawn Goddess, shed tears of dew every morning after his death in the Trojan War. The badly damaged statues were once 70 feet high and cut from a single piece of quartzite stone. Around them are sugar cane fields. The pair of statues, each depicting the seated Amenhotep III, once stood at the first pylon, or gateway, of the pharaoh’s enormous mortuary temple in Thebes. For millennia, the 70-foot-tall statues were almost all that remained of the once 95-acre complex.

Colossi of Memnon Originally built for the vast mortuary temple of Amenhotep III (1441-1375 B.C.) of the Eighteenth Dynasty the statutes were intended to guard the gates of his temple. Ancient Greek travelers named the northern statue "Memnon." It became known in classical literature as "the singing Memnon" because at sunrise it would emit strange sounds. Some tourists heard human voices, others thought they heard harp strings. In the Greek-era “Guide to Greece” a traveler named Pausanias wrote they sounded “very like the twang of a broken lyre-string or a broken harp-string.” Word spread and the colossi became the one of the ancient world’s greatest tourist attractions.

The sound was produced by a crack created by an earthquake in 27 B.C. Historian Daniel Boorstin wrote: “The skeptical Greek geographer Strabo (63 B.C.-A.D. 24) suspected a machine installed by the temple priests. When Hadrian and his wife, Sabina, arrived in A.D. 130, the singing Memnon remained silent on their first morning. But it spoke up the next day and inspired their court poetess to compose a paean to both Memnon and the emperor. Emperor Septimius Severus in A.D. 202 was not so fortunate. When the statue repeatedly refused to speak to him, he tried to conciliate it by repairing its cracks. Never again was the statue heard to sing."

The colossi now stands 65 feet tall and are all that remains of the once huge Amenhotep Mortuary Temple. It was once thought they were all that was left of a huge collection of statues but recent excavations have revealed that a large number of statues — including 72 of the lion-head goddess Sekhmet and two huge statues of Amenhotep III, each flanked by a smaller one of Queen Tye and various sacred animals such as an alabaster hippopotamus — lie underground or have been excavated and placed in storerooms. There used to be a total of 730 statues here: one for every day and night in the year.

Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III

Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III (excavation at the Colossi of Memnon) was once the largest and most impressive temple complex in the world. Known as “The House of Millions of Years,” it embraced gates, colonnades, courts filed with reliefs and inscriptions, and halls with columns more than 15 meters high. In its day it was filled with colorful royal banners hanging from cedar poles on red granite pedestals. Amenhotep III called the complex “a fortress of eternity” and said it was built “out of good white sandstone — worked with gold throughout. Its floors were purified with silver, all of its doorways were of electrum” — an alloy of gold and silver. Over the centuries, though, earthquakes, floods and looting, much of it by 19th century Europeans, have reduced the temple to buried ruins.

Larger than Vatican City and more vast than the massive Karnak and Luxor temples, the Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III was the length of seven football fields and stretched from the colossi to sacred altars pointing towards the Valley of the Kings. During Amenhotep III’s rule the Nile flowed just a few hundred meters away from the temple. The Colossi of Memnon once stood in front of it. The massive front gate, or pylon, was once brightly painted in blues, red,, greens, yellows and whites.

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology Magazine: No building project of Amenhotep III’s compared to his mortuary temple, one of the grandest religious structures ever built. The entire temple precinct was once surrounded by a painted mudbrick wall that enclosed more than four million square feet, or around 95 acres. The first pylon, or main entrance, was guarded by two colossal statues of the seated king. A grand processional way then led through two additional elaborate pylons, the gates of which were flanked by a pair of giant statues of Amenhotep III as well. It then entered a great peristyle court with a forest of columns shaped like bundles of papyrus where hundreds of free-standing statues were installed. Near the rear of the complex was a temple dedicated to Amun-Ra, as well as the mortuary temple proper of Amenhotep III, where the dead king received the gifts and offerings that would sustain him in his journey through the afterlife. Two 45-foot-tall statues of the pharaoh Amenhotep III that once flanked the Northern Gate of his mortuary temple have recently been pieced together from fragments and restored to their original position. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

Although Amenhotep III, like other pharaohs, called his mortuary temple the House of Millions of Years, in actuality it only lasted for a century and a half. Around 1200 B.C., a devastating earthquake reduced it to ruins. Its stones, bricks, statues, and other materials were carted off to be reused in nearby construction projects and to adorn new temples, especially those of the pharaohs Ramesses II and Merneptah (r. ca. 1213–1203 B.C.). What was left was periodically flooded, until most of the sanctuary was covered in six to 10 feet of alluvial deposits. The greatest temple in ancient Egypt had all but disappeared. All that remained were the two gargantuan statues of Amenhotep III sitting at what had once been the temple’s main entrance. The northern statue was named Memnon by the Romans who associated it with the Ethiopian Trojan War hero-king Memnon, these behemoths each weigh more than 720 tons and rise to a height of nearly 70 feet. For more than 3,000 years, they towered above the Nile plain, but little else of the original structure was visible — that is, until the late 1990s,

Archaeology and Restoration at Amenhotep III’s Mortuary Temple

The Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III has been excavated since 1999 by a team led by Baghdad-born, Armenian archeologist Hourig Sourouzian. There is some sense of urgency to the project as archeologists are worried about salty runoff and irrigation water groundwater and seepage from the Nile damaging the sculptures that are underground. The restoration plan calls for much of the temples to be reconstructed but that will take many years — even decades — to complete. Just piecing statues and columns back together take a lot of time. Sections are being completed and opened bit by bit.

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology Magazine: In the 1990s Sourouzian began to lament the condition of the ruins and wonder what might still be buried beneath the surface. “The colossi were all you saw,” she says. “There were some column bases and fallen fragmented sculptures, but it looked like a field. I said, ‘I wish someone could do something to save this ruined temple.’” Sourouzian, with Rainer Stadelmann of the German Archaeological Institute and a few colleagues, made a proposal to the Egyptian authorities. They founded the Colossi of Memnon and Amenhotep III Temple Conservation Project, of which she is the current director. Over the past two and a half decades, her team has grown from a few scholars and a handful of workers to a total of more than 300. Their goal is to save the last remains of the temple from further degradation and to at least partially restore the parts that were felled by the earthquake or damaged by the passage of time.[Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

The focus of Sourouzian’s project is mainly conservation rather than excavation, but she has occasionally found it necessary to dig in certain areas. To date, the team has reconstructed part of the peristyle court, which was once adorned with two huge stone stelas recording Amenhotep III’s accomplishments, as well as dozens of statues of the pharaoh and sculptures depicting sphinxes, a crocodile, a hippopotamus, falcon gods, and other deities. They have also discovered hundreds of statues of the lion-headed goddess Sekhmet that once lined the court’s walls and passageways. Discovering such a great number of representations of the goddess is extraordinary, explains Sourouzian. “That our project would find so many was really a surprise,” she says.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Rediscovering Egypt's Golden Dynasty” in Archaeology magazine archaeology.org

Two King Amenhotep III Colossal Sphinxes Discovered

In January 2022, archaeologists announced that they had discovered two colossal limestone sphinxes with King Amenhotep III’s face. An Egyptian-German archaeological team found the statues, which were originally about 8 meters (26 feet) long in Thebes (modern-day Luxor) at the mortuary temple of King Amenhotep III, which was called the "Temple of Millions of Years" by ancient Egyptians. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, published January 25, 2022]

The two colossi show Amenhotep III wearing a mongoose-shaped headdress, a royal beard and a broad necklace, Mustafa Waziri, secretary-general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, said in the statement. A restoration revealed an inscription across the chest of one of the colossi that read "the beloved of Amun-Re," a reference to Amenhotep III. "This temple housed a large number of statues, models and wall decorations, before it was hit by a devastating earthquake in 1200 B.C.," Egyptolologist Hourig Sourouzian, the head of the archaeological mission, told Al-Monitor.

The archaeologists — from the the Colossi of Memnon and Amenhotep III Temple Conservation Project — also found three fairly well-preserved statues of the powerful goddess Sakhmet (also spelled Sekhmet), who is portrayed as having the head of a lion on the body of a woman. The Sakhmet statues were located at the façade of an open interior courtyard, known as a peristyle court. "In the peristyle, the newly discovered pieces of wall relief reveal new scenes of the Heb-Sed, a festival of the king started after 30 years of his rule and repeated every three years thereafter," Sourouzian told Al-Monitor.

Karnak Temple Under Amenhotep III

Elaine Sullivan of UCLA wrote: “Amenhotep III’s initial work at Karnak was a continuation of the activities of his father centered on the festival court of Thutmose II. He finished the decoration on his father’s shrine and likely added a northern door to the mud-brick precinct wall aligned with the hall’s north-south axis. Later, he dramatically re-envisioned the temple, tearing down the pylon erected by Thutmose II and destroying most of the festival court west of the fourth pylon. He built a new pylon to the east, the third pylon, using stone blocks of the removed structures in its foundation and fill. The western half of Thutmose IV’s peristyle, his calcite bark-shrine, the limestone White Chapel of Senusret I, the calcite chapel of Amenhotep I, and the loose blocks of the Red Chapel of Hatshepsut all fell victim to the renovations. [Source: Elaine Sullivan, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Amenhotep III began construction on a new pylon (the tenth) to the south of Hatshepsut’s eighth pylon, extending the southern processional route towards the Mut Temple. While building was still at its beginning stages, he had two colossal statues of himself placed flanking the pylon entrance. With only a few courses completed on the pylon, the king must have died, as construction halted and was not to be resumed until the reign of Horemheb.

“Two other important structures built by Amenhotep III, both of whose exact location within the precinct remains unknown, attest to some of the less-documented aspects of the temple’s role in the city as a center of storage and production. Sandstone blocks from the “granary of Amun” have been found reused as fill in the towers of the second pylon. Contemporary Theban tomb scenes portray the granary as a structure with multiple rectangular rooms, each heaped high with mounds of grain. A second building, a shena- wab, was the site of the preparation of temple offerings. Parts of an inscribed stone door from this building were uncovered near the ninth and tenth pylons, and the shena-wab may have been located in the southeast quarter of the precinct.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024