Home | Category: New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut)

QUEEN HATSHEPSUT

Queen Hatshephut

as a small sphinx Queen Hatshepsut was the only female to rule Egypt as a full pharaoh in a period when Egypt was strong. Often depicted as a man with a false beard, she rose to power after claiming divine birth. Her name means “the first, repeatable lady.” Other women ruled but they did so in weak period. Twosret was another female ruler. She ruled from 1198 B.C. to 1190 B.C. One, possibly two, other female pharaohs ruled briefly. Cleopatra came along 14 centuries after Hatshepsut. She wasn’t a Pharaoh or even full-blooded Egyptian but rather a Greek that ruled over the remains of a kingdom established by Alexander the Great. [Source: Chip Brown, National Geographic. April 2009; Elizabeth Wilson, Smithsonian magazine, September 2006; Peter Schjeldahl, The New Yorker]

Hatshepsut (Hatchepsut) was the Queen of Egypt during the 18th Dynasty. The daughter of Thutmose I, she married Thutmose II. When he ascended to the throne she became the real ruler. When he died she acted as regent for his son, Thutmose III, then had herself crowned as Pharaoh. Maintaining the fiction that she was a male, she was represented with the regular pharaonic attributes, including a beard. Hatshepsut built a magnificent funerary temple at Deir el-Bahri on the west bank of the Nile at Thebes and sent a large commercial expedition to the land of Punt, in modern Ethiopia. [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003; [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Queen Hatshepsut ruled from 1479 to 1458 B.C. She was referred to by both male and female pronouns depending on the situation but was regarded politically as an “honorary man.” There was no Egyptian word for "Her Majesty." People addressed her as "His Majesty." Bas-reliefs and statues often depict her with a lion’s mane and a male headdress in addition to the false beard.

Hatshepsut is thought to have been quite beautiful when she was young. At least that way it seems when you see images of her early in her rule. Even when she is portrayed a man she has soft feminine, features, a rounded chin and gently protruding breasts. Her mummy indicated she had an overbite as did other members of her family. Images of her when she was older depict her as heavy and haggard.

On seeing her in a number of art works at an exhibition. The New Yorker’s Peter Schjeldahl wrote, “Hatshepsut is no Nefertiti. Even in colossal statuary, she’s more pleasant-looking than anything else — a woman whose appearance except for over-the-top eye make-up would not have startled one in a Midwestern mall...She often smiles slightly, projecting confident oneness with divinity.”

See Separate Article: HATSHEPSUT REIGN (1479 TO 1458 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

”Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh” by Joyce A. Tyldesley (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Woman Who Would Be King” by Kara Cooney (2014) Amazon.com;

“Hatchepsut: The Life of the Female Pharaoh (1507 - 1458 BCE 18th Dynasty)”

by Ron Schaefer Amazon.com;

“Thutmose III and Hatshepsut, Pharaohs of Egypt: Their Lives and Afterlives” by Aidan Dodson (2025) Amazon.com;

“When Women Ruled the World: Six Queens of Egypt” by Kara Cooney (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Temple of Hatshepsut, the Solar Complex (Deir El-bahari, 6) by Janusz Karkowski (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Southern Room of Amun in the Temple of Hatshepsut: History and Epigraphy: With an Appendix Multidisciplinary Project” by Izabela Uchman (Deir El-bahari, 10)

by Katarzyna Kapiec (2023) Amazon.com;

“Guide To The Temple Of Deir El Bahari” (1894-5) Amazon.com;

“The Cleopatras: Discover the Powerful Story of the Seven Queens of Ancient Egypt!” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (2024) Amazon.com;

“King and Goddess” by Judith Tarr (1996), Novel Amazon.com;

“Child of the Morning” by Pauline Gedge (1976) Novel Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom" by Joyce Tyldesley (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume III: From the Hyksos to the Late Second Millennium BC” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East” by Amanda H Podany (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Temples, Tombs, and Hieroglyphs: A Popular History of Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz (1978, 2009) Amazon.com;

Hatshepsut’s Family Background

Seniseneb, Hatshepsut's grandmother

Joyce Tyldesley of the University of Manchester wrote for the BBC: “ Hatshepsut was a royal princess, the eldest daughter of the great general Thutmose I and his consort Queen Ahmose. Ahmose had failed to provide her husband with a male heir, but that did not matter overmuch; the royal harem could furnish an acceptable substitute. Prince Thutmose, son of a respected secondary queen, was married to his half sister Hatshepsut, and eventually succeeded to the throne unchallenged as Thutmose II.” [Source: Dr Joyce Tyldesley, University of Manchester, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “Hatshepsut was descended from a number of strong women, including Aahotep, the mother of King Ahmose I. Aahotep was a military leader and she received the “Golden Flies” awarded to soldiers who fought courageously. When Ahmose died, his son Amenhotep became pharaoh but he left no male heirs. Thutmose I, a commoner and army general, became king by marrying Amenhotep’s sister Nefertiri. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

Although Thutmose had three sons and two daughters by his great wife, only one of these children was alive when he died: the twelve-year-old Hatshepsut. Thutmose did have a son by a minor wife, also called Thutmose, and to strengthen his claim to the throne, this son was married to Hatshepsut. However, Thutmose II suffered from poor health and reigned for only fourteen years. He left a daughter by Hatshepsut and a son, again called Thutmose, by Isis, a harem girl. It is possible that Thutmose II realized Hatshepsut was ambitious for power because he proclaimed the young Thutmose his successor. But when he died Thutmose III was still a child, and his aunt and stepmother, Hatshepsut, acted as regent for him. ^^^

Tyldesley wrote for the BBC: “Hatshepsut, now queen of Egypt, bore her husband/brother a daughter, Princess Neferure, but no son. When Thutmose II died suddenly, after a mere three years on the throne, a dynastic crisis threatened. Again there was a prince in the royal harem, but this time the prince was a baby. Under normal circumstances the royal mother would act as regent for her son; unfortunately the mother in this case was a lady of unacceptably low status. A compromise was reached. The infant Thutmose III would become king under the temporary guidance of his stepmother, the dowager Queen Hatshepsut. |::|

Queen Hatshepsut’s Family

Thutmose I

Hatshepsut was born around 1507 B.C. to Thutmose I and his great royal wife, Queen Ahmose. Thutmose I had no royal blood. Ahmose was his principal and most blue-blooded wife. Ahmose was the daughter of a great Pharaoh, also named Ahmose, which gave Hatshepsut a unique advantage because she had more royal blood in her than either Thutmose I, or his son Thutmose II or grandson Thutmose III.

Hatshepsut was born around the time of her father’s coronation in 1504 B.C. She appears to have idolized her father, later having him reburied in a tomb she built for herself, and claimed that soon after her birth he selected her to succeed him — a claim that seems unlikely. Hatshepsut’s grandfather, Ahmose I, defeated the Hyksos who had invaded Lower Egypt and occupied it for more than one hundred years, and launched the New Kingdom and the 18th dynasty, one of the most extraordinary periods of ancient Egyptian history.

When Hatshepsut was about 12 she married her half-brother — Thutmose II, the son of Thutmose I by a different wife — making her the Queen of Egypt before she was a teenager. When Thutmose II died young, probably when he was in his 20s, Hatshepsut became the regent for Thutmose III, her stepson, nephew and the legitimate heir. Thutmose III was still a child when his father Thutmose II died. His mother was a harem girl.

Hatshepsut gave birth to a single child, a daughter named Neferure, with Thutmose II. Some archaeologists and historians believe that Senenmut, Hatshepsut’s chief advisor and the architect of her great mortuary temple, was the father. Statues exist that show him cuddling Neferure, who died when she was 16. There is also a crude drawing scrawled in the tomb of man thought to be Senemut having sex with a woman in pharaonic headdress. Most historians think Hatshepsut was not involved with him physically because she had too much to lose if word got she was. In any case, Senemut was a very important figure; 25 known monuments were raised to honor him, a staggering number for a non-royal, and some even claim he was the brain and real power behind the throne. More likely, in the words of The New Yorker’s Peter Schjeldahl, he was her Sir Walter Raleigh.

Hatshepsut’s Divine Birth

The following is an account of Hatsheput’s “divine” birth inscribed with reliefs at her mortuary temple: “Amun summoned the Great Ennead in heaven to him and proclaimed to them his decision to procreate for the land of Egypt a new king, and he promised to the gods all good through it. As successor, Hatshepsut was chosen the unique woman; the royal office for her was claimed. "She builds your chapels," said Amun to the Ennead. "She consecrates your temples . . . she makes you rich offerings . . . the dew of heaven shall fall in her time . . . and the Nile shall be high in her time. Surround her with your protection, with life, happiness unto eternity." [Source: Translated from Emma Brunner-Traut, AltEgyptische Marchen, 5th ed. (Dusseldorf und Ksln, 1979), pp. 76-87. Internet Archive, from Creighton]

“The Ennead answered, "We have come herewith. We surround her with our protection, with life and happiness . . . " Amun charged Thoth, the god of wisdom and messenger, to seek Queen Iahmes, the wife of the reigning king, whom he selected as the future mother of the successor, and Thoth answered him as follows: "This young woman is a princess. She is called Iahmes. She is more beautiful than all the women in the whole land. She is the wife of the king, the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Thutmose I, and his majesty is still a youth. Go therefore to her . . ." Then Thoth led Amun to Queen Iahmes.

“There came the ruling god, Amun, Lord of the throne of the Two Lands, after he had assumed the form of the majesty of her husband, the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Thutmose I. He found her as she rested in the innermost (area) of her palace. Then she awoke because of the scent of the god, and she smiled at his majesty. At the same time, he went there to her and was full of desire for her. He gave her his heart and allowed her to recognize him in his divine form, after which he approached her. She rejoiced to show her beauty, and his love went over into her body. The palace was flooded with the fragrance of the god. All his scent was the fragrance from Punt.

Thutmose III and Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut before Amun

Thutmose III was born to a secondary wife of Thutmose I not to Queen Ahmose, Thutmose I’s principal and most blue-blooded wife, like Hatsheput was. The account of Hatsheput’s “divine” birth goes: “The royal wife and king's mother Iahmes spoke to the majesty of the splendid god Amun, to the lord of the throne of the Two Lands, "My lord, how great is your glory. How splendid it is to see your face. You have enclosed my majesty with your glance. Your fragrance is in all my parts." [Thus she spoke,] after the majesty of this god had done with her all which he wished. [Source: Translated from Emma Brunner-Traut, AltEgyptische Marchen, 5th ed. (Dusseldorf und Ksln, 1979), pp. 76-87. Internet Archive, from Creighton]

Then Amun, the lord of the throne of the Two Lands spoke to her, "Hatshepsut is thus the name of this your daughter whom I have laid in your body, according to the speech of your mouth. She will exercise the splendid kingship in the whole land. My glory will belong to her, my authority will belong to her, and my crown will belong to her. She will rule the Two Lands (Egypt) . . . I will surround her every day with my protection in common with the god of the respective day."

“After Amun attended the queen, determined the name of the child, and promised her the lordship over Egypt, he spoke with the creator god Khnum who would form the child on the potter's wheel from mud. Thereby he commissioned him to create for the child a ka. And Khnum answered him : "I form this your daughter prepared for life, prosperity, and health, for food, nourishment, for respect, popularity, and all good. I distinguish her form from the gods in her great dignity of king of Upper and Lower Egypt."

“Then according to the divine instruction, Khnum created the royal child Hatshepsut and her ka on the potter's wheel, and the goddess of birth, the frog-headed Heket, proffered life to her. Khnum spoke in addition, "I form you with this divine body . . . I have come to you to form you completely as all gods (Kings), give to you all life and prosperity, give to you enduring and joy . . . and give to you all health, deliver to you all flat lands and all mountain lands as well as all subjects, give to you every food and nourishment and cause that you appear on the throne of Horus like (the sun god) Re (himself). I cause that you stand as the head of all the living when you appear as king of Upper and Lower Egypt. Thus as your father Amun-Re who loves you has commanded it."

“Khnum's divine companion Heket concluded with speeches of blessing and gave the child with her word, life, enduring, and happiness in all eternity. The divine messenger Thoth, dispatched by Amun, proclaimed to the royal mother Iahmes the office and title which heaven had conferred on her. He called her "the daughter of Geb, heir of Osiris, princess of Egypt, and mother of the king of Egypt. Amun the lord of the throne of the Two Lands is content with your great dignity of Princess who is great of favor, cheerfulness, charm, loveliness, and popularity," and his message to the great royal wife Iahmes concluded with the wish that she live, endure, be happy and everlastingly joyful in heart.

“Khnum, the creator god, and his divine companion Heket conducted the pregnant queen to the birth and the birth place and there pronounced their blessings. Khnum spoke to her, "I surround your daughter with my protection. You are great, but the one who opens your womb will be greater than all kings till now . . . " Thus spoke Khnum, the potter . . . and Heket, the deliverer. The queen who accordingly immediately became pregnant and now suffers the birth pains was delivered in the presence of the god Amun and goddess of the birth place Mesekhnet with the assistance of many spirits and divine nurses. After a long speech by Amun, Mesekhnet executed her blessing on the child.”

See Separate Article: THUTMOSE III (1480-1426 B.C.): ANCIENT EGYPT’S GREATEST RULER? africame.factsanddetails.com

Queen Hatshepsut’s Rule

defaced Hatshepsut Relief Queen Hatshepsut took power from Thutmose III and attained unprecedented power for a woman. She ruled for 21 years (from 1479 B.C. to 1473 B.C. as the regent of Thutmose III and 1473 B.C. to 1458 B.C. as Pharaoh and co-ruler with Thutmose III). Her father, Thutmose II, did not rule for long. When he died Thutmose III was just a boy and Hatshepsut was named his regent and took effective control of the kingdom. Early on she seemed to play her role as expected. She was careful to respect convention and did not overstep her herself. The earliest reliefs depict her as a queen standing by Thutmose III, who is portrayed as an adult king performing pharaonic duties.

But as time went on Hatshepsut became bolder. Early reliefs after Thutmose II’s death show her making offering to the gods and ordering an obelisk from Aswan. Within a few years she assumed the role of “king” and relegated her stepson to second-in-command. It is not clear what her motive was. Some have suggested it was a hunger for power. Other have said it was an effort to reinstate royal blood — and the divinity associated with it — to the ruling dynasty. Yet others say she took power to avoid a palace coup brewing while her stepson was still too young to act.

During Hatsheput’s rule, the Egyptian economy expanded and trade flourished. She dispatched a major sea-borne expedition to Punt (Somalia) on the African coast and the southern part of the Red Sea. The walls her mortuary temple at Deir el Bahri are illustrated with a colorful account of expedition to Punt. There are images of ships, a marching army led by her general, Nehsi. Based on drawings, expedition brought back gold, ebony, animal skins, baboons, and refined myrrh as well as living myrrh trees that were then planted around the temple. The walls at Deir el Bahri also depict the houses seen in Punt and an image of its obese queen. [Source :Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

See Separate Article: HATSHEPSUT REIGN (1479 TO 1458 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

Hatshepsut’s Death

Harshepsut died suddenly around 1480 B.C. Whether she died naturally or was deposed and eliminated is not known. As Hatshepsut and her political allies aged, her hold on the throne weakened. The early death of her daughter, whom she had married to Thutmose III, may have contributed to her decline. Eventually, her nephew took his rightful place as pharaoh, though the circumstances of this event are unknown.

Egyptian officials have said that the mummy of Hatshepsut suggests the woman was obese, probably suffered from diabetes, had liver cancer and died in her 50s. In 2011, Associated Press reported that researchers at the University of Bonn in Germany discovered a carcinogenic substance in a flask of lotion believed to have belonged to Queen Hatshepsut, raising a possibility she may have accidentally poisoned herself. The university said it spent two years researching the dried-out contents of the flask, which is part of its Egyptian Museum's collection and bears an inscription saying it belonged to Hatshepshut. [Source: Associated Press, August 19, 2011]

Researchers said the flask contains what appears to have been a lotion or medicine used to tackle skin disorders such as eczema. The contents included palm and nutmeg oil, along with fatty acids of the kind that can relieve such disorders. There are known to have been cases of skin diseases in Hatshepsut's family, the university said.

Researchers also found benzopyrene, an aromatic and highly carcinogenic hydrocarbon. "If one imagines that the queen had a chronic skin disease and the ointment gave her short-term relief, then she may have exposed herself to a major risk over the course of a few years," Helmut Wiedenfeld of the university's pharmaceutical institute said in a statement.

Identifying Queen Hatshepsut’s Lost Mummy

Hatshepsut’s sarcophagus was discovered by Howard Carter in tomb K20 in the Valley of the Kings in 1903, but her mummy was not inside. The sarcophagus was reused for Hatshepsut’s father, Thutmose I. For decades archaeologists looked for the mummy of Hatshepsut and had no luck finding it. Carter, the discoverer of King Tut’s tomb, found two sarcophagus’s bearing Hatshepsut’s name along with some limestone wall panels and a canopic chest in a tomb in the Valley of the Kings labeled KV20 in 1903 but found no mummy. He did however find “two much denuded mummies of women and some mummified geese” nearby in a minor tomb known as KV60 in 1920. One of the mummies — a fat one — was in a coffin. The other — a skinny one — lay on the floor. Carter took the geese and closed the tomb. Three years later another archaeologist took the fat mummy in the coffin to the Egyptian Museum. The inscription on the coffin was later linked to Hatshepsut’s nurse. The skinny mummy on the floor was left where it was.

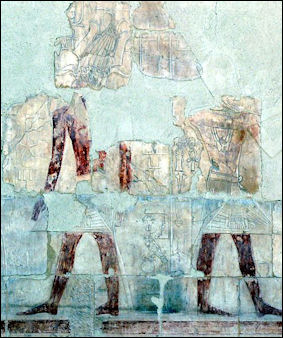

Queen Hatshepsut in a wall painting

in her mortuary temple In the late 2000s, an effort was launched to identify Queen Hatshepsut’s mummy with CT (computerized tomography) scans and DNA analysis. There were four possible candidates. The two mummies found KV60. The one brought to the Egyptian Museum in the 1920s was still sitting there unidentified for decades. The second skinny one was brought to the museum. The two other candidates came from a cemetery next to Hatshepsut’s funerary temple. They were selected because a small box with Hatshepsut’s name on it was found in the tomb that housed them.

The whole thing was set up, of course, by Egyptologist Zahi Hawass. CT scans were taken of the four mummy candidates and their images where compared with images of mummies belonging to Hatshepsut relatives. The scans revealed little that was conclusive in identifying them. The key to identifying Hatshepsut’s mummy turned out to be a small box with Hatshepsut’s cartouche inscribed on it. Sealed with embalming fluid, the box was thought to contain some of Hatshepsut’s organs, most likely her liver. Because it was regarded as inappropriate to break open the box, a CT scan was taken instead. It showed the box contained a tooth — a secondary molar with part of its root missing.

As it tuned out the molar perfectly fit into a gap in the jaw of one of the mummies — the fat one that had been brought to the Egyptian Museum in the 1920s — thus identifying it, as best as could be expected, a Hatshepsut’s mummy. Not everyone saw the tooth as slam-dunk proof. Some scholars, for example, raised questions about the box with the tooth as it was not a typical canopic vessel.

The investigation of the mummies also provided clues on how Hatshepsut died. Evidence from the CT scan of her mummy seemed to indicate she died from an infected abscess in her gums, perhaps worsened by bone cancer or diabetes. The mummy itself seemed to lack the elaborate send off you would expect of a royal burial. There was no golden mask, no jewelry, none of the things found in burial of King Tutankhamun. Hawass initially thought that Hatshepsut’s mummy was the least likely of the four candidates to be her because she was fat and had “huge pendulous breast” of the sort more likely to be found on the queen’s wet nurse.

After Queen Hatshepsut’s Death

After Harshepsut died, Thutmose III became the leader of Egypt. About 20 years after he became pharaoh, someone ordered the defacing of Hatshepsut’s monuments and replaced her name with Thutmose I, II, or III — her father, her husband and stepson — in an effort to erase her name from history. Many believe the defacement was ordered by Thutmose III. Ironically, some of the best-preserved obelisks in Egypt are those of Hatshepsut. Thutmose III had stone walls built around them to hide them from public view, but these walls also helped preserve and protect them.

After Hatshepsut’s death there was a massive defacing campaign. Eyes were gouged out of reliefs. Images of her as king were systematically chiseled of temples, monuments and obelisks. Heads were loped off statues. Entire rows of statues were toppled over into pits. As we said before it is believed that Thutmose III was behind it. Images of Senenmut, Hatshepsut’s chief advisor, were also defaced.

It is ironic that Thutmose III inherited an economically strong Egypt from Hatshepsut, that provided the foundation for his accomplishments and the greatness of the New Kingdom achieved. With his military training and a strong, stable Egypt to stand on, Thutmose III conquered foreign lands and brought such great wealth to Egypt that he, arguably, made making it the world’s first super power.

Did Thutmose III Order the Attacks on Hatsheput’s Monuments

Thutmose III

Joyce Tyldesley of the University of Manchester wrote for the BBC: “Soon after her death in 1457 B.C., Hatshepsut's monuments were attacked, her statues dragged down and smashed and her image and titles defaced. The female king vanished from Egyptian history. She would remain lost until, almost three thousand years later, modern Egyptologists reconstructed her damaged inscriptions and restored her to her rightful dynastic place. |[Source: Dr Joyce Tyldesley, University of Manchester, BBC, February 17, 2011]

“The Egyptians believed that the spirit could live beyond the grave, but only if some remembrance-a body, a statue, or even a name-of the deceased remained in the land of the living. Hatshepsut had effectively been cursed with endless death. Who could have done such a terrible thing, and why? Thutmose III, stepson and successor to Hatshepsut, seems the obvious culprit, but we should not condemn him unheard. There are two major crimes to be considered before we draw any conclusion. |::|

“It is undeniable that someone attacked Hatshepsut's monuments after her death. Archaeology indicates that the bulk of the vandalism occurred during Thutmose' reign. Why would he do this? At first it was imagined that this was the new king's immediate revenge against his stepmother; he was indeed cursing her with permanent death. The image of the young Thutmose seething with impotent rage as Hatshepsut ruled in his place is one which has attracted amateur psychologists for many years. However, it does not entirely fit with the known facts. |::|

“Thutmose was to prove himself a calm and prudent general, a brave man not given to hasty or irrational actions. He did not start his solo reign with an assault on Hatshepsut's memory; indeed, he allowed her a traditional funeral, and waited until it was convenient to fit the desecration into his schedule. Some of the destruction was even carried out by his son, after his death, when most of those who remembered Hatshepsut had also died. It is a remote, rather than an immediate, attack. Furthermore the attack is not a thorough one. Enough remained of Hatshepsut to allow us to recreate her reign in some detail. Her tomb, the most obvious place to start the attack, still housed her name. Hatshepsut may have been erased from Egypt's official record, but she was never hated as Akhenaten 'The Great Criminal' would later be. |::|

“What can we conclude from this tangled tale? We should perhaps rethink our assumptions. Hatshepsut did not fear Thutmose; instead of killing him, she raised him as her successor. Thutmose may not have hated Hatshepsut. Initially he may even have been grateful to her, as she had protected his land while training him for greatness. But, as he grew older and looked back over his life, his perspective would shift. Would Egypt's most successful general, a stickler for tradition, have wished to be associated with a woman co-regent, even a woman as strong as Hatshepsut? |::|

“By removing all obvious references to his co-ruler Thutmose could incorporate her reign into his own. He would then become Egypt's greatest pharaoh; the only successor to Thutmose II. Hatshepsut would become the unfortunate victim, not of a personal attack, but of an impersonal attempt at retrospective political correctness. |Thutmose set his masons to re-write history. Their labours would last well into the reign of his successor, Amenhotep II, a king who could not remember Hatshepsut, and who had no reason to respect her memory. Meanwhile, hidden in the Valley of the Kings, Hatshepsut still rested in her coffin. Thutmose I had been taken from their joint tomb and re-buried, but she had been left alone. Thutmose knew that as long as her body survived, Hatshepsut was ensured eternal life.” |::|

Hatshepsut’s Mummy Reveals She Was a Fat and Balding

Describing Hatshepsut’s mummy after it was put on display at the Egyptian Museum, Chip Brown wrote in National Geographic, “her mouth, with the upper lip shoved over the lower, was a gruesome crimp...her eye socket was packed with blind black resin, her nostrils unbecomingly plugged with tight rolls of cloth, her left ear had sunk into the flesh in the left side of her skull, and her head was almost completely without hair...The only human touch was in the bone shine of her nailed fingertips, where the mummified flesh had shrink back, creating the illusion of a manicure.”

The CT scans of Hatshepsut’s mummy also revealed that she was a fat, balding and bearded Meredith F. Small, an anthropologist at Cornell, wrote in Live Science: “Turns out, Hatshepsut...was a 50-year-old fat lady; apparently she used her power over the Upper and Lower Nile to eat well and abundantly. Archaeologists also claim that she probably had diabetes, just like many obese women today. Hatshepsut also suffered from what all women over 40 need—a stylist. She was balding in front but let the hair on the back of her head to grow really long, like an aging female Dead Head with alopecia. This Queen of Egypt also sported black and red nail polish, a rather Goth look for someone past middle age. [Source: Meredith F. Small, Live Science, July 6, 2007]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024