Home | Category: New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut)

RAMSES THE GREAT

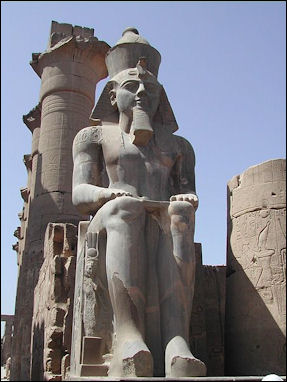

Ramses II Colossal statue Ramses II, also known as Ramses the Great, was perhaps the greatest of all the Egyptian pharaohs. He became Pharaoh in 1279 B.C. when he was in his twenties and the pyramids were already 1,300 years old. He ruled ancient Egypt for 68 years during the golden age of the civilization. He raised more temples, obelisks and colossal monuments that any other Pharaoh and ruled an empire that stretched from present-day Libya and Sudan to Iraq and Turkey. The Bible refers to him simply as "Pharaoh." [Source: Rick Gore, National Geographic, April 1991 [♣]

During Ramses II's lifetime (approximately 1303 B.C. to 1213 B.C.), the pharaoh led military campaigns that expanded Egypt's borders and funded elaborate building projects along the Nile, including Abu Simbel and an enormous the temple complex of Ramesseum. Many artifacts of Ramses' reign still survive, including an 83-ton granite statue of the king. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, July 20, 2022]

Ramses means "Son of Ra." According to the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum in San Jose, California, Ramses II stood over 1.8 meters (6 feet) — tall by ancient Egyptian standards. " He had a strong jaw; a beaked nose, a long thin face," says James Harris of the University of Michigan, who X-rayed the Pharaoh's mummy, "That was not typical of earlier pharaohs. He probably looked more like the people of the eastern Mediterranean. Which is not surprising, because he came from the Nile delta, which had been invaded in the past by peoples from the east."♣

Ramses died at the age of 92 or 96. Having outlived many of his older sons, his 13th son ascended to the throne upon his death in 1298 B.C. Within 150 years after he was buried Ramses tomb was looted and the mummy was desecrated.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

"Ramesses II, Egypt's Ultimate Pharaoh" by Peter Brand Amazon.com;

“Pharaoh Triumphant. The Life and Times of Ramesses II” by Kenneth Kitchen (1990) Amazon.com;

”Pharaoh Seti I: Father of Egyptian Greatness” by Nicky Nielsen (2020) Amazon.com;

“Ramesses: Egypt's Greatest Pharaoh” by Joyce Tyldesley (2001) Amazon.com;

“Ramesses the Great: Egypt's King of Kings” by Toby Wilkinson Amazon.com;

“When Egypt Ruled the East” by George Steindorff and Keith C. Seele (1963) Amazon.com;

“The Eastern Mediterranean in the Age of Ramesses II” by Marc Van De Mieroop Amazon.com;

“Qadesh 1300 BC: Clash of the Warrior Kings” (1993) by Mark Healy Amazon.com;

“Warfare in New Kingdom Egypt” by Paul Elliott (2017) Amazon.com;

“War in Ancient Egypt: The New Kingdom” by Anthony J. Spalinger (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Mysteries of Abu Simbel: Ramesses II and the Temples of the Rising Sun” by Zahi Hawass (2001) Amazon.com;

“Colossal Statue of Ramesses II” by Anna Garnett (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Temple of Ramesses II in Abydos: Volume 1, Wall Scenes - Part 1, Exterior Walls and Courts & Part 2, Chapels and First Pylon (2 volumes)” by Sameh Iskander and Ogden Goelet (2015) Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom" by Joyce Tyldesley (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume III: From the Hyksos to the Late Second Millennium BC” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

"The New Kingdom" by Wilbur Smith, Novel (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Late New Kingdom in Egypt (c. 1300–664 BC) A Genealogical and Chronological Investigation (Oxbow Classics in Egyptology) by M. L. Bierbrier (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Temples, Tombs, and Hieroglyphs: A Popular History of Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz (1978, 2009) Amazon.com;

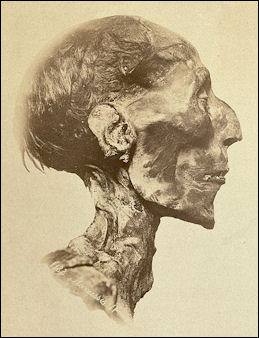

Ramses II's Mummy

The mummy of Ramses the Great has Great has a shock of soft reddish-blonde hair with the texture of peach fuzz. CT scans and studies of tissue material from Ramses II’s body in the 2000s indicate that the Pharaoh had blackheads, arthritis and hardening of the arteries. The nose of Ramses II was reinforced with animal bone and stuffed with seeds.

X-rays of the mummy done show he had arthritis of the hip, which forced him to stoop, and gum disease. Research from 2014 suggests the king had a bone condition called diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, which causes the ligaments near the spine to harden, reducing flexibility. The mummy is now at Egypt's National Museum of Egyptian Civilization. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, July 20, 2022]

In 1150 B.C., a grave robber confessed under torture to plundering the tombs of Ramses and his sons. According to Live Science: In the 11th century B.C., priests relocated royal mummies, nominally to protect them from looters. In actuality, the priests probably also wanted to pick apart these tombs for gold and raw materials, which were in short supply at the time, according to the American Research Center in Egypt. Ramses II ended up in a plain coffin in a secret cache of royal mummies at Deir el-Bahari, which was rediscovered in 1881, and a record of his journeys was written on his wrappings.

Does Ramses II Deserve to Be Called Great

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “Although he is probably the most famous king in Egyptian history, his actual deeds and achievements cannot be compared with the great kings of the 18th dynasty. He is, in my opinion, unworthy of the title ‘Great’. A show-off and propagandist, he made his mark by having his name, like a graffiti artist, inscribed on every possible stone. Whereas kings such as Thutmose III left a stronger and more dynamic Egypt, after Ramses death Egypt fell into decline. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

Ramses II's mummy head John Ray of Cambridge University wrote for the BBC:“Ramesses II is the most famous of the Pharaohs, and there is no doubt that he intended this to be so. In astronomical terms, he is the Jupiter of the Pharaonic system, and for once the superlative is appropriate, since the giant planet shines brilliantly at a distance, but on close inspection turns out to be a ball of gas. Ramesses II, or at least the version of him which he chose to feature in his inscriptions, is the hieroglyphic equivalent of hot air. [Source: John Ray, Cambridge University, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Yul Brynner captured the essence of his personality in the 1956 film “The Ten Commandments,” and in popular imagination Ramesses II has become the Pharaoh of the Exodus. The history behind this is much debated, but it is safe to say that the character of Ramesses fits the picture of the overweening ruler who refuses divine demands.The king's battle against the Hittites at Qadesh in Syria was a near defeat, caused by an elementary failure of military intelligence, and saved only by the last-minute arrival of reinforcements from the Lebanese coast. In Ramesses' account, which occupies whole walls on many of his monuments, this goalless draw turns into the mother of all victories, won single-handedly by himself. |::|

“The architectural history of Ramesses' reign must now be rewritten, in the light of recent discoveries made in Tomb 5 of the Valley of the Kings. This tomb was long believed to have been a mere false start for the king's own burial place, but it is now known to contain more than 100 chambers, arranged on varying levels and destined to receive the bodies of most of the king's sons. The monument is uniquely intriguing. |::|

“Ramesses outlived many of his sons, and was succeeded by the thirteenth, a prince named Merneptah who was already advanced in years. One of this king's first acts was to call for an inventory of the wealth of the temples, and one gains the impression that the excesses of the previous reign had left the throne close to bankruptcy. This conclusion is supported by the history of the rest of the dynasty, which is disfigured by a series of feuds between rival branches of the over-extended family. Ramesses may well deserve the epithet, 'the Great', but, like some others who are honoured with the same distinction, he left a mixed legacy. |::|

Ramses II's Family

Maite Mascort wrote in National Geographic History: Ramses’ family came to power as outsiders. They were northerners hailing from the Nile Delta and rose through military service, rather than southerners rising from elite circles in Thebes. [Source: Maite Mascort, National Geographic History, February 16, 2023]

During the 18th Dynasty most rulers believed themselves to be the progeny of a divine union between their mothers and the god Amun-Re, as claimed by Queen Hatshepsut and Pharaoh Amenhotep III, among others. But Ramses II and his successors could not claim such ancestry — because their paternal line did not descend from royalty. Ramses II’s grandfather Paramessu had been a vizier under Horemheb, the last pharaoh of the 18th dynasty.Taking the name Ramses I, Paramessu ruled a few years before his son took the throne as Seti I. Although Ramses I is technically the founder of the 19th dynasty, some consider Seti I — Ramses II’s father — the first real Ramesside king.

See Separate Article: RAMSES II'S FAMILY, QUEENS AND CHILDREN africame.factsanddetails.com

Ramses the Great as Pharaoh

Ramesses II on chariot In the seventh year of Seti I’s reign, his son Ramses II became co-ruler of Egypt. Seti died at about age 50 and Ramses became pharaoh at the age of 24. One of first duties as the new Pharaoh was to participate in the festival of Opet in Thebes. During the festival a golden statue of the supreme god Amun was carried from the Temple of Karnak by barge and by foot on a two mile journey to the temple of Luxor where Amun-Min, the phallic god of fertility, resided. The statue stayed at Luxor for about two weeks while the Pharaoh presided over an annual secret renewal ceremony that also was intended to breath new life into the Pharaoh himself.♣

Ramses was very conservative. He discouraged innovation and reform and saw his amain duty as upholding traditional Egyptian customs. Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic, More than anyone else, this great king would work to erase from history all traces of Akhenaten, Tutankhamun, and the other "heretics" of the Amarna period.”

Ramses was also considered to be very humane. He went against custom by featuring his children and wives in his monuments and reportedly was well liked by his subjects, who appeared to have been more than happy to toil and raise great monuments in his honor. In one stelae, Ramses boasted his workers "work for me with full hearts."

Ramses II’s Building Campaign

Ramses II pectoral Ramses II and his father Seti began many restoration and building projects. These included the building of several temples and the restoration of other shrines and complexes throughout Egypt. He built a mortuary complex at Abydos in honor of Osiris and the famed Ramesseum.

John Ray of Cambridge University wrote: “The traditional capitals, Memphis and Thebes, were not enough for” Ramesses II, he added his own in the Delta, modestly named Pi-Ramesse, one rendering of which would be Ramessopolis. Not even the heretic Akhenaten had dared to name his city after himself. Ramesses, however, thinks large. Previous Pharaohs had followed the rule that, in temple design, incised relief was used on the exterior walls, where it could cast strong shadows. Inside the temples, however, bas-relief was employed, since it does not produce such contrasts and creates a serene effect in the semi-dark. [Source: John Ray, Cambridge University, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“The temple-building programme instigated by Ramesses may have been rushed, but it turned out to be the most extensive ever achieved by a single Pharaoh in all Ancient Egypt's 30 dynasties, and some of the king's monuments, such as the delicate temple built at Abydos next to the larger complex of his father, show refinement and even understatement. The twin temples of Abu Simbel in Nubia, though by no means understated, are masterpieces of land-and river-scaping, as well as being political propaganda skilfully translated into stone. |::|

See Separate Article: MONUMENTS BUILT UNDER RAMSES II africame.factsanddetails.com

Ramses II’s Military Campaigns and Empire Building

Ramses II is well known for his unusually long 66-year reign and for expanding ancient Egypt's empire while also maintaining alliances with its neighbors. Artwork depicting him pharaoh often shows him as a great warrior king smiting enemies. However, according to Britannica, historical records suggest his military prowess may have been overblown. [Source Live Science]

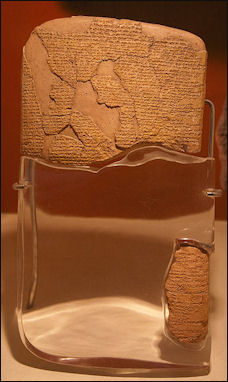

Early in his life, Ramses II went on numerous campaigns, one of which — the Battle of Kadesh — has been detailed in the poem of Pentaur, the son of Ramses III. In that poem, Ramses II is exalted as a great warrior and leader. Ramess II fought the Hittites and signed the world's first official peace treaty. He oversaw a massive building campaign.

During the reign of Ramses II, the Egyptian vast empire extended roughly from modern-day Sudan to Syria. A new capital, Pi-Ramses, was constructed at Qantir, in northeastern Egypt, and Ramses II made a peace treaty with the Hittites in which he would marry a Hittite princess.

Ramses, the Hittites and the Battle of Kadesh

Treaty of Kadesh The Egyptians and Hittites challenged one another for control of the eastern Mediterranean. The Hittites had iron weapons, the Egyptians didn’t. In 1288 B.C., the fifth year of his reign, Ramses and his young sons mounted chariots and led an army of 20,000 men — a huge number at that time — to Syria for a "superpower showdown" against the Hittite king Muwatallis, whose a force was nearly twice as big as the Egyptian force. ♣

At stake was Kadesh, a fortress town in Syria that guarded the trade routes to the east (the Egyptians, and probably, the Hittites imported silk from China). Seti I, Ramses father, had captured the city, but when he returned to Egypt, the Hittites recaptured it.

Ramses's army was surprised by an ambush from the Hittites outside of Kadesh and the Egyptian army scattered. According to an inscription of dubious merit, Ramses found himself abandoned but nevertheless mounted his chariot and led a charge and Egyptian reinforcements arrived and this time the Hittites were on the run. In reality the Egyptians were routed but neither side was able to gain territory on the other, so Ramses went home and raised a monument to declare his great victory.

Ramses led military campaigns against the Hittites until he was in his 40s. After 15 years of fighting the Egyptians and Hittites signed a peace treaty that proved to be so cordial that the Hittite king Hattusilis III sent his eldest daughter,Maat-Hor-Nefersure to wed Ramses II in 1246 B.C. The marriage almost didn't come off because of a last minute argument between Ramses II and Hattusilis over the dowry.

The marriage between Ramses and Maat-Hor-Nefersure ushered in a long period of peace and prosperity that lasted until Ramses' death. Ramses later married another one of Hattusilis's daughters. The Hitittes may have even sent craftsman to Egypt to make iron shields and weapons for the Egyptians.♣

See Separate Article RAMSES II, THE HITTITES AND THE BATTLE OF KADESH factsanddetails.com

Herodotus on Senusret (Ramses II)

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “Leaving the latter aside, then, I shall speak of the king who came after them, whose name was Senusret44. This king, the priests said, set out with a fleet of long ships45 from the Arabian Gulf and subjugated all those living by the Red Sea, until he came to a sea which was too shallow for his vessels. After returning from there back to Egypt, he gathered a great army (according to the account of the priests) and marched over the mainland, subjugating every nation to which he came. When those that he met were valiant men and strove hard for freedom, he set up pillars in their land, the inscription on which showed his own name and his country's, and how he had overcome them with his own power; but when the cities had made no resistance and been easily taken, then he put an inscription on the pillars just as he had done where the nations were brave; but he also drew on them the private parts of a woman, wishing to show clearly that the people were cowardly. 103. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“He marched over the country doing this until he had crossed over from Asia to Europe and defeated the Scythians and Thracians. Thus far and no farther, I think, the Egyptian army went; for the pillars can be seen standing in their country, but in none beyond it. From there, he turned around and went back home; and when he came to the Phasis river, that King, Senusret, may have detached some part of his army and left it there to live in the country (for I cannot speak with exact knowledge), or it may be that some of his soldiers grew weary of his wanderings, and stayed by the Phasis.

T“Now when this Egyptian Senusret (so the priests said) reached Daphnae of Pelusium on his way home, leading many captives from the peoples whose lands he had subjugated, his brother, whom he had left in charge in Egypt, invited him and his sons to a banquet and then piled wood around the house and set it on fire. When Senusret was aware of this, he at once consulted his wife, whom (it was said) he had with him; and she advised him to lay two of his six sons on the fire and make a bridge over the burning so that they could walk over the bodies of the two and escape. This Senusret did; two of his sons were thus burnt but the rest escaped alive with their father.

“After returning to Egypt, and avenging himself on his brother, Senusret found work for the multitude which he brought with him from the countries which he had subdued. It was these who dragged the great and long blocks of stone which were brought in this king's reign to the temple of Hephaestus; and it was they who were compelled to dig all the canals which are now in Egypt, and involuntarily made what had been a land of horses and carts empty of these. For from this time Egypt, although a level land, could use no horses or carts, because there were so many canals going every which way. The reason why the king thus intersected the country was this: those Egyptians whose towns were not on the Nile, but inland from it, lacked water whenever the flood left their land, and drank only brackish water from wells.

“For this reason Egypt was intersected. This king also (they said) divided the country among all the Egyptians by giving each an equal parcel of land, and made this his source of revenue, assessing the payment of a yearly tax. And any man who was robbed by the river of part of his land could come to Senusret and declare what had happened; then the king would send men to look into it and calculate the part by which the land was diminished, so that thereafter it should pay in proportion to the tax originally imposed. From this, in my opinion, the Greeks learned the art of measuring land; the sunclock and the sundial, and the twelve divisions of the day, came to Hellas from Babylonia and not from Egypt.

“Senusret was the only Egyptian king who also ruled Ethiopia. To commemorate his name, he set before the temple of Hephaestus two stone statues, of himself and of his wife, each fifty feet high, and statues of his four sons, each thirty-three feet. Long afterwards, Darius the Persian would have set up his statue before these; but the priest of Hephaestus forbade him, saying that he had achieved nothing equal to the deeds of Senusret the Egyptian; for Senusret (he said) had subjugated the Scythians, besides as many nations as Darius had conquered, and Darius had not been able to overcome the Scythians; therefore, it was not just that Darius should set his statue before the statues of Senusret, whose achievements he had not equalled. Darius, it is said, let the priest have his way.

“As to the pillars that Senusret, king of Egypt, set up in the countries, most of them are no longer to be seen. But I myself saw them in the Palestine district of Syria, with the aforesaid writing and the women's private parts on them. Also, there are in Ionia two figures of this man carved in rock, one on the road from Ephesus to Phocaea, and the other on that from Sardis to Smyrna. In both places, the figure is over twenty feet high, with a spear in his right hand and a bow in his left, and the rest of his equipment proportional; for it is both Egyptian and Ethiopian; and right across the breast from one shoulder to the other a text is cut in the Egyptian sacred characters, saying: “I myself won this land with the strength of my shoulders.” There is nothing here to show who he is and whence he comes, but it is shown elsewhere. Some of those who have seen these figures guess they are Memnon, but they are far indeed from the truth. “

Costs of Ramses II’s Long Reign

Maite Mascort wrote in National Geographic History: Ramses had no problems siring heirs with his many wives during his long life, but these sons would be forced to be patient; their father held tightly to his throne for almost 70 years. Ramses had placed his children liberally throughout Egypt’s bureaucracies, corporations, priesthood, and military to foster loyalty he did not naturally inspire. He was an outsider, a northerner hailing from the Nile Delta, disconnected from the wealthy elites in southern Thebes. Ramses’ source of strength rested on ties to not the moneyed or religious classes, but the military. Placing his sons in powerful positions across Egypt helped strengthen Ramses’ hold in these areas.

By the time Ramses II died in 1213 B.C., he was around 90 years old and had outlived many of these sons. Amenherkhepshef, Ramses’ oldest son and crown prince, died when he was 25 years old. Khaemwaset also did not outlive his great father and died in his mid-50s around 1215 B.C. It would be a child of Isetnofret, her son Merneptah, who was 13th in line, who succeeded Ramses. Merneptah was around 60 years old, well past middle age, when he became pharaoh and donned Egypt’s double crown.

After decades of waiting in the wings to take power, Merneptah might have expected a stable reign, like his father’s, but his hopes were in vain. During his 10-year reign, his troops were able to defend Egypt successfully from a series of attacks from enemies in the east and west. But the seeds sown by Ramses II would lead to chaos after Merneptah’s death; rivals for the throne, some of whom may have been sons of Ramses II, pushed Egypt into a period of decline and civil war. By around 1189 B.C. the 19th dynasty would come to an end.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024