Home | Category: Old and Middle Kingdom (Age of the Pyramids)

FALL OF THE OLD KINGDOM

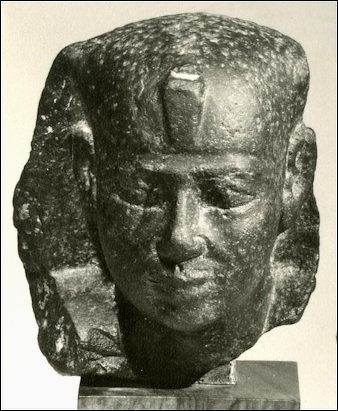

Kneeling Pepi I The Old Kingdom ended when the central administration collapsed in the late Sixth Dynasty. This collapse seems to have resulted at least in part from climatic conditions that caused a period of low Nile waters and great famine. The kings would have been discredited by the famine, because pharaonic power rested in part on the belief that the king controlled the Nile flood. In the absence of central authority, the hereditary landowners took control and assumed responsibility for maintaining order in their own areas. The manors of their estates turned into miniature courts, and Egypt splintered into a number of feudal states. This period of decentralized rule and confusion lasted from the Seventh through the Eleventh dynasties. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

There was a severe 200-year drought in North and East Africa around 2200 B.C. Hieroglyphics record that the annual Nile flood failed for about 50 years and many people died in famine. This may have produced the collapse of the Old Kingdom and the period of chaos that followed.

At the beginning of the 5th dynasty the Pharaohs ceded some of their power to a rising class of nobles. Egypt fragmented into several rival principalities and the Old Kingdom collapsed into something resembling a police state. The decline is indicated today by the presence of noblemen tombs in the districts where they ruled instead of around the pyramids of the pharaohs. The pyramids built during this period were of inferior quality to those built before.

Professor Fekri Hassan wrote for the BBC: “Nothing prepared Egypt for the eclipse of royal power and poverty that came after Pepy II (Neferkare). He had ruled for more than 90 years (2246-2152 B.C.) as the fourth king of the 6th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom. Within the span of 20 years, fragmentary records indicate that no less than 18 kings and possibly one queen ascended the throne with nominal control over the country. This was the entire length of the 7th and 8th Dynasties (2150-2134 B.C.). In the last few years of the 6th Dynasty, the erosion of power of the centralized state was offset by that of provincial governors and officials who became hereditary holders of their posts and treated their regions as their own property. [Source: Professor Fekri Hassan, BBC, February 17, 2011, Professor Fekri Hassan is from the Institute of Archaeology, University College London. His areas of interest include the cultural dynamics of state formation in Ancient Egypt, the role of gender in the early religious and political developments in rock art and the attributes of the earliest Egyptian goddesses]

Renate Mueller-Wollermann of the University of Tuebingen wrote: “In previous decades, Egyptologists explained the decline of the Old Kingdom by a growing decentralization of the administration and economy that led to the weakness, and eventually collapse, of the central state. More recently, climatic causes—specifically increasing desiccation— have been both proposed and denounced. An entirely new proposal was brought forward by Jansen-Winkeln, who claimed that an attack by foreigners from the northeast was feasible.” [Source: Renate, Mueller-Wollermann, University of Tuebingen, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2014, escholarship.org ]

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RELATED ARTICLES:

OLD KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT (CA. 2649–2150 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com ;

OLD KINGDOM DYNASTIES (3RD THROUGH 6TH) OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

RULERS OF THE OLD KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AGE OF THE PYRAMIDS AND THE PHARAOHS THAT BUILT THEM africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PYRAMIDS OF ANCIENT EGYPT: HISTORY, COMPONENTS AND TYPES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

BUILDING THE PYRAMIDS: RAMPS, ENGINEERING FEATS, MATERIALS AND QUARRYING AND CUTTING THE STONES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PYRAMID BUILDERS africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Death, Power, and Apotheosis in Ancient Egypt: The Old and Middle Kingdoms”

by Julia Troche (2021) Amazon.com;

“Analyzing Collapse: The Rise and Fall of the Old Kingdom” by Miroslav Bárta , Aidan Dodson, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

“Descendants of a Lesser God: Regional Power in Old and Middle Kingdom Egypt”

by Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano (2023) Amazon.com;

“A History of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2: From the Great Pyramid to the Fall of the Middle Kingdom” by John Romer (2012) Amazon.com;

"In the Shadow of the Pyramids: Egypt during the Old Kingdom" by Jaromir Malek, Many illustrations (1986) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume I: From the Beginnings to Old Kingdom Egypt and the Dynasty of Akkad” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, D. T. Potts, Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

"Towards a New History for the Egyptian Old Kingdom – Perspectives on the Pyramid Age" by Peter Der Manuelian (Author) (2015) Amazon.com;

"The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders" by Naguib Kanawati and Nigel Strudwick Amazon.com;

"Domain of Pharaoh: the Structure and Components of the Economy of Old Kingdom Egypt" by Hratch Papazian Amazon.com;

"Egypt in the Eastern Mediterranean During the Old Kingdom: an Archaeological Perspective" by Karin N. Sowada and Peter Grave (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com; Wilkinson is a fellow of Clare College at Cambridge University;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt:The Definitive Visual History” by Steven R. Snape (2021) Amazon.com;

Fragmentation and Decentralization of the Old Kingdom

Pepi II

Renate Mueller-Wollermann of the University of Tuebingen wrote: “The administration of the latter half of the 6th Dynasty is characterized by increasing decentralization. More and more posts were taken over by officials in the provinces and made de facto inheritable. Especially noteworthy is the number of provincial viziers, although some of these viziers may be titular. Many, but not all, nomes were governed by a nome administrator, who was often also the overseer of the priests of the main temple of the nome. These officials were responsible for recruiting manpower— especially soldiers, as a standing army did not exist. The training and recruiting of troops, Nubian mercenaries included, was increased, and forts were erected, in Balat, for example, or on the Sinai coast. [Source: Renate, Mueller-Wollermann, University of Tuebingen, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2014, escholarship.org ]

“Prior to the reign of Pepy II most of the holders of the office of Overseer of Upper Egypt—responsible for the collection of taxes—were buried at the royal residence, only a few being buried in the provinces. Upon Pepy II’s reign, however, the situation was reversed. The nomes in the Delta, however, seem to have been administered from the royal residence. The number of royal domains increased in the 6th Dynasty, but not in those regions with major temples, such as el-Hawawish, Elkab, or Coptos. This indicates that royal domains and temples took over the same task—that is, to supply the royal residence with provisions.

“The increasing number of decorated tombs in the provinces produced a variety of texts and figures. Provincial tomb biographies show greater innovation and more frequent use of unconventional motifs than those in the royal residence. The quality of decoration in provincial tombs, however, declined and the scenes became increasingly less elaborate, due to, among other possible factors, the smaller size of many of the tombs. The decoration of tombs in the southern provinces in particular, where contact with skilled craftsmen from the royal residence was limited, shows a return to simplicity. In general, tomb decoration, including statues, exhibits a new, “second style” that became manifest in the representation of exceptionally long bodies, narrow waists, and wide eyes. Some scholars, however, have claimed that the canon of proportions did not change.”

Professor Fekri Hassan wrote for the BBC: ““Contrary to what some Egyptologists claim, the stability of the long reign of Pepy II was most likely due to the decentralization of the government. This is one of the most successful strategies in managing complex organizations. The ambitions of local governors in such a system are primarily curtailed by the economic and defence rewards of being a vassal. In addition, there is the strong likelihood of failure in staging an uprising because the king can count on many more loyalists. Only when the monarchy is undermined by some unforeseen cause, would charismatic and ambitious provincial governors seek to become kings. In this situation, they stand to gain from restoring the monarchy in their name, thus counting on the support of others who, in the absence of a powerful king, would rally behind them. [Source: Professor Fekri Hassan, BBC, February 17, 2011]

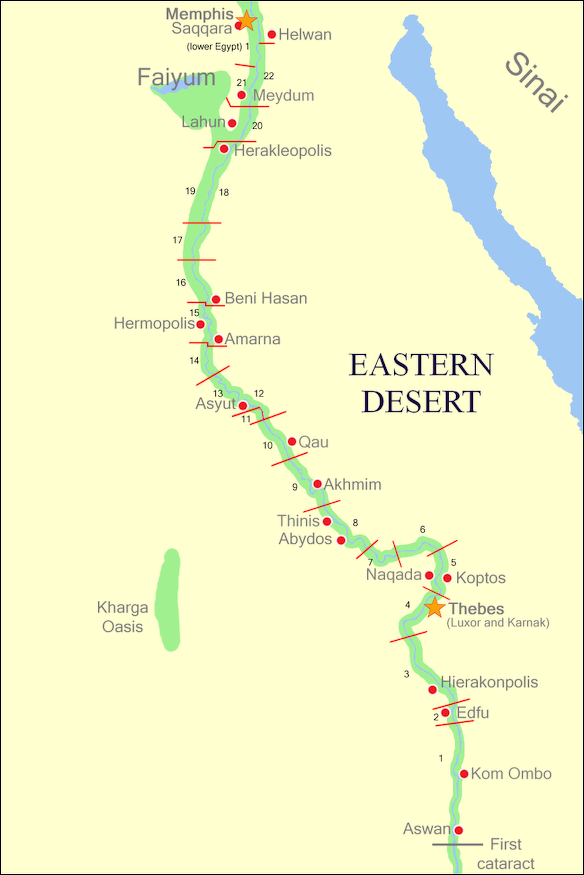

Pepi II and His Successors

Professor Fekri Hassan wrote for the BBC: ““We have no indication at the end of the 6th Dynasty that there was a bid for power by the local governors. It is only after the initial breakdown that power was wielded by the kings of a province in Middle Egypt, later called Herakleopolis. The capital was approximately 15 kilometers west of Beni Suef on the right bank of Bahr Yusuf. According to Manetho, Herakleopolis became the capital of Egypt during the 9th and 10th Dynasties and the town played a major role after the end of the Old Kingdom. Evidence for this account comes from inscriptions in the tombs of a vassal prince at Asyut. These reveal that war broke out between the kings of Herakleopolis and Theban kings. The war lasted for several years and ended when the Theban king Mentuhotep II Nebhepetre (2061-2010 B.C.) defeated Herakleopolis before re-unifying the country.[Source: Professor Fekri Hassan, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Renate Mueller-Wollermann of the University of Tuebingen wrote: “The decline of the Old Kingdom begins with the reign of Pepy II. Although the Turin Canon ascribes to him more than 90 years, there are no inscriptions later than the year after the 31st (cattle) count, which would be the 63rd year of his reign or even earlier, depending on the intervals of the count. A graffito in his pyramid at South Saqqara mentions a burial and probably the 32nd count; this may place his death in the 64th year of his reign, or earlier. [Source: Renate, Mueller-Wollermann, University of Tuebingen, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2014, escholarship.org ]

“It is confirmed that in Pepy II’s reign expeditions were made to Hatnub to quarry alabaster, the Sinai to extract turquoise and copper, Byblos to obtain timber, and Nubia to acquire gold and exotics. Furthermore, nine royal decrees from his reign are known: one at Abydos for the benefit of royal statues, four at Coptos for the benefit of the temple of Min, one at Giza for the benefit of the pyramid of Menkaura, two at Saqqara in favor of a royal person and of a non-royal individual, respectively, and one at Dakhla for the benefit of the governors of that oasis. “Pepy II’s son and successor, Nemtiemsaef/Merenra II, may have left a decree at Saqqara in order to protect the cult of two king’s mothers. In the 8th Dynasty Neferkauhor left eleven decrees, all in Coptos. His successor, Demedjibtaui, also left a decree in Coptos. From these 8th-Dynasty decrees we learn that Neferkauhor protected an official and the official’s son, but subsequently withdrew his favor from them, and that later his successor attempted to protect the official and his son again.

“The location of the pyramids of the 6th- Dynasty kings who reigned after Pepy II remains unknown. Of the pyramids of the 8th Dynasty, only that of Ibi has been located, in the vicinity of Pepy II’s pyramid in South Saqqara.”

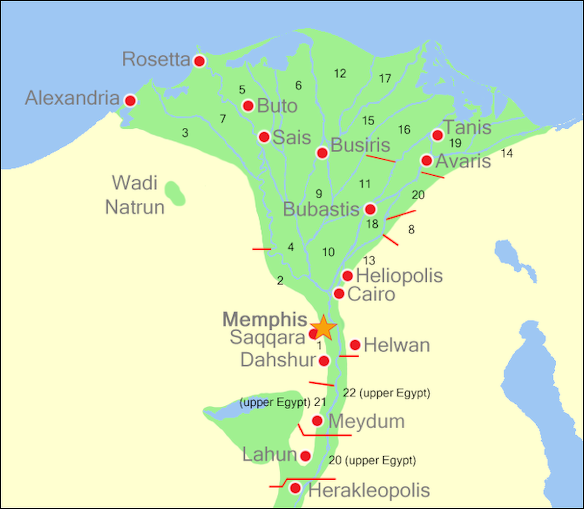

Lower Egypt nomes

Causes of the Decline of the Old Kingdom

Renate Mueller-Wollermann of the University of Tuebingen wrote: “There is no single cause that can be pinpointed to account for the decline of the Old Kingdom. Rather, the reasons are manifold, and it is difficult to determine their weight. Proposed internal causes include an economic weakening of the central government due to the exemption of the temples from duties; an administrative weakening due to the growing bureaucracy and inheritability of offices; and a political weakening caused by the increasing autonomy of the provinces and their governors. It is possible that the weakness of the central government was more significant than the strength of the provinces. Indeed the long reign of Pepy II produced a great number of potential successors and therefore possible rivalries following his death. [Source: Renate, Mueller-Wollermann, University of Tuebingen, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2014, escholarship.org ]

“Economic reasons for the decline have very recently been rejected, since the income of the royal residence was based on the residence’s own domains situated throughout the country, and no overall tax system existed. Less recently, administrative causes were excluded, as the balance of power between the royal residence and the provinces does not seem to have been disturbed. Possible external political causes have recently been brought forward by Jansen- Winkeln, who maintains that the proposed internal reasons are not sound and that all the Egyptian empires were brought down by foreign invasions. In his view the rapid changeover from the Old Kingdom to the First Intermediate Period, the lack of documents of the elite in the Delta in the First Intermediate Period, the shift of the residence from Memphis to Herakleopolis, and the Teaching of Merikara all speak in favor of a foreign invasion. Excavations at Mendes, however, perhaps not yet noticed by Jansen- Winkeln, reveal the destruction of the town and the murder of its inhabitants at the end of the 6th Dynasty—that is, before the end of the Old Kingdom.

Miroslav Bárta wrote: It is interesting to observe that the factors formerly representing the backbone of ancient Egyptian kingship and the state—that is, the growth of the elite class of administrators, the penetration of the state administration by non-royal officials, the centralization of the government, and the management of resources by means of redistribution—gradually became negative factors from the Fifth-Dynasty reign of Niuserra onward. [Source: Miroslav Bárta, head of the Czech Institute of Egyptology’s Abusir Mission, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2017]

These negative factors, all centered around the malfunction of both the central administration and the royal residence, manifested themselves in the following forms: as a crisis of identity (i.e., the degree to which the ruling group was accepted); as a crisis of participation (i.e., which individuals took part in the state’s administration and in what capacity); as a crisis of the ability of the state’s executive power to control the administration and economy; as a crisis of legitimacy (i.e., which individuals had the authority and ability to enforce decisions); as a crisis of distribution (i.e., the effectiveness of the redistribution of economic sources); and, finally, as a two-fold economic crisis (i.e., while worsening climatic conditions had a direct bearing on agricultural output, the intensive transfer of landholdings from the state to the non-taxable funerary domains—the purpose of which was to provide an economic base for both royal and non-royal cults and the plethora of officials involved—constituted a maneuver that led to the eventual exhaustion of the economic capacities of the country). Generally speaking, by the end of the Old Ki ngdom the powers of the formerly centralized government had become territorial and personal.

Did Climate Change Cause of the Fall of the Old Kingdom

Why the Old Kingdom collapsed is still a a matter of debate among scholars, but research indicated that drought and climate change played a significant role. During this time, cities and civilizations in the Middle East also collapsed, with evidence at archaeological sites indicating that a period of drought and arid climate hit sites across the region. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

Renate Mueller-Wollermann of the University of Tuebingen wrote: “ “Climatic changes have also been suggested to account for the Old Kingdom’s decline. Hassan was one of the first and most decisive supporters of the hypothesis that reduced Nile floods in conjunction with the invasion of desert sand in the Nile Valley led to desiccation of the land, and consequently to famines. Sand dunes in the area of Abusir were noticed since the reign of Tety . The exact dates of the occurrence of droughts, however, are difficult to determine and therefore it cannot be stated with certainty whether droughts occurred before or after the end of the Old Kingdom. According to Bárta they indeed accelerated the decline of the Old Kingdom. [Source: Renate, Mueller-Wollermann, University of Tuebingen, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2014, escholarship.org ]

“Buto appears to have been abandoned at the end of the Old Kingdom, probably due to a shift in the course of a nearby waterway, rather than to external or internal political reasons. A similar situation occurred in Memphis, which no longer offered ideal conditions for a royal residence subsequent to an eastward shift of the Nile.”

See Separate Article: CLIMATE CHANGE IN ANCIENT EGYPT: GREEN SAHARA, DROUGHT, EMPIRE COLLAPSE? africame.factsanddetails.com

Upper Egypt nomes

Consequences of the End of the Old Kingdom

Renate Mueller-Wollermann of the University of Tuebingen wrote: “Upon the end of the Old Kingdom, the territorial entity of the Egyptian state disintegrated; the position of the king, however, was not put into question. In Upper Egypt the end of the kingdom led to civil strife wherein coalitions of (some) nomes fought against other coalitions, famines plaguing a number of nomes, while others had ample resources. The situation in Lower Egypt is unclear. In general, the importance of nomes decreased in comparison to that of towns. The most obvious result of the end of the Old Kingdom was the cessation of Egypt’s relations with foreign countries and expeditions into mining regions, with a resultant lack of exotic goods and loss of prestige. [Source: Renate, Mueller-Wollermann, University of Tuebingen, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2014, escholarship.org ]

“Several literary texts have traditionally been considered to describe the situation in Egypt following the end of the Old Kingdom, such as the “Teaching for Merikara,” the “Admonitions of Ipuwer,” and the “Prophecies of Neferti.” It is, however, unclear exactly when these texts were composed and which time period(s) they describe—and whether they describe an actual situation at all. In recent years the “Admonitions of Ipuwer” were dated to the end of the 12th, or to the 13th, Dynasty and the “Teaching for Merikara” and “Prophecies of Neferti,” as late as the 18th Dynasty. A king Neferkara (probably Pepy II) is held in bad repute in the “Tale of Neferkara and the General Sasenet,” a text transmitted from the New Kingdom onwards, which recounts the king’s homosexual relationship with his army general Sasenet.”

Professor Fekri Hassan wrote for the BBC: “There are four successive episodes during this upheaval of Egyptian civilisation. First came the initial episode of shock, upheaval and fragmentation which were caused by low floods. This lasted from the end of the 6th Dynasty to the end of the 8th (perhaps as early as 2100 and certainly by 2155-2134 B.C.). Then came the second episode of rehabilitation and re-development of regional polities which commenced c.2134 B.C. This encompassed the first two generations after the end of the 8th Dynasty (the 9th in Herakleopolis) and the first part of the 10th in Thebes. This was followed by the struggle between Thebes and Herakleopolis during the reign of Antef I who succeeded in re-establishing order during his 50-year reign. This incidentally did not lead to any weak successors. Finally occurred the consolidation of national unity by Mentuhotepe II and his immediate successors after c.2020 B.C. [Source: Professor Fekri Hassan, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Rebirth Of Ancient Egypt After the Old Kingdom Collapse

Professor Fekri Hassan wrote for the BBC: “Egypt, to be sure, survived the disastrous collapse of the monarchy. Within a century, Egyptians had re-invented centralized government. They refurbished the image of kings so that they were not merely rulers by virtue of their divine descent but more importantly had to uphold order and justice, care for the dispossessed and show mercy and compassion. The crisis that shook Egyptian society thus heralded the most dramatic transformation in the royal institution, which was destined never to be separated from this social function. [Source: Professor Fekri Hassan, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“The crisis not only reformed the monarchy but also instilled the spirit of social justice and laid the foundation for mercy and compassion as fundamental virtues. It was these concepts that were later to infuse Christianity and Islam. It was these same concepts that eventually led to the overthrowing of monarchs who repeatedly usurped their powers and denied people their religious rights. |::|

“It was the Herakleopolitan kings from Bahr Yusuf who restored order and stability as the Nile floods allowed the return of plentiful harvests. This was perhaps after 20-30 years of low floods. In the meantime, the Theban rulers began to position themselves to appropriate and resurrect the tattered monarchy. They were on a collision course with the Herakleopolitan kings who, as texts reveal, lost to their southern rivals. However, the Herakleopolitan legacy of that period which emphasised notions of justice, mercy, and social services were never extinguished. Some of the treatise detailing these notions became Egyptian classics. They include the instructions attributed to Herakleopolitan King Khety to his son Merikare. In these instructions, the king stressed the social obligations of the king and advised the heir to the throne to remember that god created godly rulers to fortify the backbones of the weak and counteract the blows of fate.

“Within the context of the Herakleopolitan society of the early 12th Dynasty, The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant, was certainly disseminated as a piece of official wisdom. It is clearly a bill of rights of ordinary citizens and the responsibility of state officials towards the poor and powerless. The tale regards the ruler as a father to the orphan, husband to the widow, brother to she who is divorced, a garment to the motherless, a just ruler who comes to the voice of those who call him. |::|

“The end of the Old Kingdom was not the end of Egyptian civilization. The so-called 'First Intermediate' period was not a Dark Age. The calamity triggered by low Nile floods was the impetus to radical social changes and a reformulation of the notion of kingship. The legacy of this period is still with us today. |::|

First Intermediate Period (2150-2130 B.C.)

The First Intermediate Period lasted roughly from 2150 to 2030 B.C. and that encompassed dynasties seven to 10 and part of 11. During this time central government in Egypt was weak and the country was often controlled by different regional leaders. Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: As the governors became more autonomous, increasing political and climatic instability after the end of the 6th Dynasty led to the fall of the Old Kingdom and the beginning of a period of political fragmentation known by scholars as the First Intermediate Period (ca. 2150–2030 B.C.).

The term "Intermediate" is used to describe periods when there was no strong centralized government unifying the Upper and Lower Egypt. During the first Intermediate Period there was dynastic rule both in the North (at Herakleopolis), and in the South (at Thebes). In the south, local officials did not acknowledge the northern kings, instead governing the provinces (called nomes) in their own right. The attempts to reunify the land fostered sporadic internal conflicts and civil wars. Over time the governors of Thebes in Upper Egypt established Dynasty 11 and competed with the Heracleopolitan kings by gaining dominion over the south as far as the first Cataract. [Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica, Thomson Gale, 2007; New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003]

During the First Intermediate Period Egypt became a group of states headed by warlords grouped loosely in confederations of north and south. This schism lasted for 700 years. At the beginning of this period one scholar wrote, "All the pyramids were looted, not secretly at night but by organized bands of thieves in broad daylight...The temples were burned. There was widespread violence. And a desperate famine took hold of the land."

Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt fought against one another. Poverty and hunger became widespread. Inscriptions show droughts, sandstorms and women forced to eat fleas to survive. One inscription read: "I gave bread to those who were hungry and clothes to those who were naked...All of Upper Egypt was dying of hunger, to the point where children were eating their own children." Another read, "The entire country had become like a starved locust.”

See Separate Article: FIRST INTERMEDIATE PERIOD (2150-2030 B.C.) OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024