Home | Category: Old and Middle Kingdom (Age of the Pyramids) / Life (Homes, Food and Sex) / Economics

LABOR USED TO BUILD THE PYRAMIDS

Thousands of laborers were used to build the pyramids. Some historians claim they were slaves forced into working by cruel supervisors. Other historians say the workers were reasonably paid and happy to have a job. [Sources: Virginia Morrell, National Geographic, November 2001; David Roberts, National Geographic, January 1995]

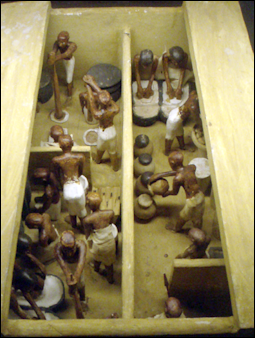

The people who built the pyramids were likely made up of several thousand highly-skilled and well-paid craftsmen supported by thousands of manual laborers. Based on the number cattle, goats and sheep consumed it has been estimated that there were 6,000 to 7,000 workers at the site at one time, many times more if they only ate meat on special occasions. Supporting the pyramid builders were bakers, brewers and butchers and other service people.

Dr Joyce Tyldesley of the University of Manchester wrote: “All archaeologists have their own methods of calculating the number of workers employed at Giza, but most agree that the Great Pyramid was built by approximately 4,000 primary labourers (quarry workers, hauliers and masons). They would have been supported by 16-20,000 secondary workers (ramp builders, tool-makers, mortar mixers and those providing back-up services such as supplying food, clothing and fuel). This gives a total of 20-25,000, labouring for 20 years or more. The workers may be sub-divided into a permanent workforce of some 5,000 salaried employees who lived, together with their families and dependents, in a well-established pyramid village. There would also have been up to 20,000 temporary workers who arrived to work three-or four-month shifts, and who lived in a less sophisticated camp established alongside the pyramid village. [Source: Dr Joyce Tyldesley, University of Manchester, BBC, February 17, 2011]

RELATED ARTICLES:

LIFE OF THE PYRAMID BUILDERS africame.factsanddetails.com

MERER'S DIARY: 4,600-YEAR-OLD LOGBOOK ABOUT PYRAMID WORKERS africame.factsanddetails.com

PYRAMIDS OF GIZA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PYRAMIDS OF ANCIENT EGYPT: HISTORY, COMPONENTS AND TYPES

africame.factsanddetails.com

BUILDING THE PYRAMIDS: LAYOUT, ENGINEERING, ALIGNMENT africame.factsanddetails.com

PYRAMID RAMPS AND PUTTING THE STONES IN PLACE africame.factsanddetails.com

BUILDING MATERIALS FOR PYRAMIDS — QUARRYING, CUTTING AND MOVING THE STONES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt” by A. David (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Builders of the Pyramids” by Zahi Hawass (2009) Amazon.com;

“Sticks, Stones, and Shadows: Building of the Egyptian Pyramids” by Martin Isler (2001) Amazon.com;

“Mountains of the Pharaohs: The Untold Story of the Pyramid Builders” by Zahi Hawass (2024) Amazon.com;

”The Pyramid Builder: Cheops, the Man behind the Great Pyramid” by Christine El Mahdy (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Pyramids” by Mark Lehner (1997) Amazon.com;

“Giza and the Pyramids: The Definitive History” by Mark Lehner and Zahi Hawass (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Egyptian Pyramids: A Comprehensive, Illustrated Reference” by J.P. Lepre (1990, 2006) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Pyramids and Mastaba Tombs” by Philip J. Watson (2009) Amazon.com;

“How the Great Pyramid Was Built” by Craig B. Smith (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Secret of the Great Pyramid: How One Man's Obsession Led to the Solution of Ancient Egypt's Greatest Mystery”, Illustrated, by Bob Brier, Jean-Pierre Houdin (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Great Pyramid: 2590 BC Onwards - an Insight into the Construction, Meaning and Exploration of the Great Pyramid of Giza” By Franck Monnier, Dr. David Lightbody (2019) Amazon.com;

“ Pyramid (DK Eyewitness Books) by James Putnam (2011) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

How Many People Were Needed to Build the Pyramids

Based on inscriptions describing the quantities of garlic, radishes and onions consumed, the Greek historian Herodotus wrote in the 5th century B.C. that a 100,000 laborers working simultaneously in three month shifts spent 20 years building the Great Pyramid of Khufu (Cheops).

Scholars now suggest that it probably took 20,000 to 30,000 men, setting stones at a rate of one every two minutes, approximately 20 years to set the 2.3 million blocks (five million tons of rock) needed to build the 481-foot-high Great Pyramid of Cheops. To prove this a team led by Egyptologist Mark Lehner of the University of Chicago built a 30-foot-high pyramid and then extrapolated how much labor was needed to build a larger one. Some say the work could have been done by as few as 500 hundred skilled craftsmen and 5,000 laborers.

Jimmy Dunn wrote in touregypt. net: Kurk Mendelssohn, an American mathematician and physicist believed there were as many as 50,000 men involved with the Great Pyramid's construction based on calculations needed to move a given mass over a given distance. Ludwig Borchardt and Louis Croon, in their investigations, estimated that the Meidum pyramid would have required some 10,000 men to complete. Applying these calculations to the larger Great Pyramid, they estimated that a work force of some 36,000 men would have been required for that project. However, even this smaller workforce seemed too high to them, given the limited area of the construction site and the difficulties connected to logistics support. [Source: Jimmy Dunn, touregypt.net]

Verner tells us that the current consensus among Egyptologists sets the figure at a little more than 30,000.Lehner, who has worked at Giza for many years and conducted experiments on building pyramids, is considered one of the leading authorities on these structures. He claims a somewhat lower estimate, including carpenters to make tools and sledges, metal workers to make and sharpen cutting tools, potters to make pots for food preparation and hauling water for mortar and other purposes, bakers, brewers and others, consisting of between 20,000 and 25,000 workers at any one time. In fact, as the pyramid grew, fewer and fewer men were probably required, for work at the top required much less stone and the construction space became more limited. This number of men, which was probably drastically reduced during the agricultural seasons, probably finished the Great Pyramid of Khufu in less than 23 years. =

Pyramid Building Workers

Egyptologists Mark Lehner and Zahi Hawass believe that Giza housed a contingent of full-time workers who labored on the Pyramids year-round and a larger group of temporary seasonal workers. During the summer and early autumn wet season, when the Nile flooded large swaths of agricultural land, a large labor force of farmers and local villagers unable to work their fields appeared at Giza to work on the Pyramids. [Source: PBS, NOVA, February 4, 1997]

The workers worked hard. Exhumed skeletons show many workers had compressed vertebrae, likely the result of carrying heavy loads, and even missing fingers and limbs. Some had healed fractures and successful amputations. Most died in their thirties. The bodies of excavated women also showed considerable wear and tear and some scholars believe they may have been pyramid builders too. Laborers who died on site were buried in the town cemetery along with the tools of their trade.

Most of the pyramid builders were paid conscripts. Some were full-time employees. An inscription on a tomb of a priest judge buried near the pyramid builders city read: “I paid them in beer and bread, and I made them make an oath that they were satisfied.

Archaeologists believe that the pyramid workers believed in the importance of the task. The workers were fed, housed and clothed. Inscriptions on the stones reading the "Boat Gang," "Craftsman Gang," ''Friends of Menkaure'', “The Pure ones of Khufu," “Those Who Know Unas," “The Drunks of Menkaure," “Friends of Khufu," "Vigorous Gang," "Enduring Gand," and "Sound Gang," apparently made by the teams of workers appear to show they were proud to be a part of the monument building process.

Were the Pyramid Builders Full-Time or Part-Time Workers?

In the past, Egyptologists had theorized that the pyramid builders were largely made up of seasonal agricultural workers but the translations of 4600-year-old Red Sea scrolls appear to indicate that the gang led by Merer were not agricultural workers and they did much more much more than help with pyramid construction. These workers appear to have traveled over much of Egypt, possibly as far as the Sinai Desert, carrying out various construction projects and tasks that had been assigned to them. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, July 1, 2022]

How Were the Pyramid Builders Paid?

The Merer papyri describes members of the work team regularly getting textiles that were "probably considered as a kind of money at that time," Pierre Tallet, an Egyptology professor at Paris-Sorbonne University who is deciphering the papyri and is co-leader of the team that found them, told Live Science. Additionally, officials in high-ranking positions who were involved in pyramid construction "might have received grants of land," said Lehner. Historical records show that at times in Egypt's history, land grants were given out to officials. However, it's unknown whether land grants were also given to officials involved with pyramid construction. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, July 1, 2022]

Dr Joyce Tyldesley, University of Manchester: “Thousands of manual labourers were housed in a temporary camp beside the pyramid town. Here they received a subsistence wage in the form of rations. The standard Old Kingdom (2686-2181 B.C.) ration for a labourer was ten loaves and a measure of beer. We can just about imagine a labouring family consuming ten loaves in a day, but supervisors and those of higher status were entitled to hundreds of loaves and many jugs of beer a day. These were supplies which would not keep fresh for long, so we must assume that they were, at least in part, notional rations, which were actually paid in the form of other goods-or perhaps credits. In any case, the pyramid town, like all other Egyptian towns, would soon have developed its own economy as everyone traded unwanted rations for desirable goods or skills...As we might expect, their hurried graves were poor in comparison with those of the permanent workers who had a lifetime to prepare for burial at Giza. [Source: Dr Joyce Tyldesley, University of Manchester, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Work Done By The Pyramid Builders

On men cutting the stones and setting them, mark told PBS: Well, it's different between the core stones which were set with great slop factor, and the casing stones which were custom cut and set, one to another, with so much accuracy that you can't get a knife blade in between the joints. [Source: PBS, NOVA, February 4, 1997]

One of the things the NOVA experiment showed me that no book could is just how many men can get their hands a two- or three-ton block. You can't have 50 men working on one block; you can only get about four or five, six guys at most, working on a block — say, two on levers, cutters, and so on. You put pivots under it, and as few as two or three guys can pivot it around if you put a hard cobble under it. There are all these tricks they know. But it's just impossible to get too many men on a block. So then you figure out how many stones have to be set to keep up with this rate, to do it all in 20 years. It actually requires 5,000 or fewer men, including the stone-setters. Now, the stone-setting gets a bit complicated because of the casing, and you have one team working from each corner and another team working in the middle of each face for the casing and then the core. And I'm going to gloss over that.

But the challenge is out there: 5,000 men to actually do the building and the quarrying and the schlepping from the local quarry. This doesn't count the men cutting the granite and shipping it from Aswan or the men over in Tura [ancient Egypt's principal limestone quarry, east of Giza].

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence we have is graffiti on ancient stone monuments in places that they didn't mean to be shown. Like on foundations when we dig down below the floor level, up in the relieving chambers above the King's chamber in the Great Pyramid, and in many monuments of the Old Kingdom — temples, other pyramids. Well, the graffiti gives us a picture of organization where a gang of workmen was organized into two crews, and the crews were subdivided into five phyles. Phyles is the Greek word for tribe. The phyles are subdivided into divisions, and the divisions are identified by single hieroglyphs with names that mean things like endurance, perfection, strong.

Okay, so how do we know this? You come to a block of stone in the relieving chambers above the King's chamber. First of all, you see this cartouche of a King and then some scrawls all in red paint after it. That's the gang name. And in the Old Kingdom in the time of the Pyramids of Giza, the gangs were named after kings. So, for example, we have a name, compounded with the name of Menkaure, and it seems to translate "the Drunks (or the Drunkards) of Menkaure. " There's one that's well-attested, in the relieving chambers above the King's chamber in the Great Pyramid, "the Friends of Khufu Gang. " This doesn't sound like slavery, does it?

In fact, it gets more intriguing, because in certain monuments you find the name of one gang on one side of the monument and another gang, we assume competing, on the other side of the monument. You find that to some extent in the Pyramid temple of Menkaure. It's as though these gangs are competing. So from this evidence we deduce that there was a labor force that was assigned to respective crew, gang, phyles, and divisions.

Managing and Organizing the Pyramid Workforce

Dr Joyce Tyldesley, University of Manchester: “The tombs of the supervisors include inscriptions relating to the organisation and control of the workforce. These writings provide us with our only understanding of the pyramid-building system. They confirm that the work was organised along tried and tested lines, designed to reduce the vast workforce and their almost overwhelming task to manageable proportions. [Source: Dr Joyce Tyldesley, University of Manchester, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“The splitting of task and workforce, combined with the use of temporary labourers, was a typical Egyptian answer to a logistical problem. Already temple staff were split into five shifts or 'phyles', and sub-divided into two divisions, which were each required to work one month in ten. Boat crews were always divided into left-and right-side gangs and then sub-divided; the tombs in the Valley of the Kings were decorated following this system, also by left-and right-hand gangs. |::|

“At Giza the workforce was divided into crews of approximately 2,000 and then sub-divided into named gangs of 1,000...These gangs were divided into phyles of roughly 200. Finally the phyles were split into divisions of maybe 20 workers, who were allocated their own specific task and their own project leader. Thus 20,000 could be separated into efficient, easily monitored, units and a seemingly impossible project, the raising of a huge pyramid, became an achievable ambition. |::|

“As bureaucracy responded to the challenges of pyramid building, the builders took full advantage of an efficient administration, which allowed them to summon workers, order supplies and allocate tasks. It is no coincidence that the 4th Dynasty shows the first flourishing of the hieratic script, the cursive, simplified form of hieroglyphics that would henceforth be used in all non-monumental writings.” |::|

Structure of the Pyramid-Building Labor Force

Jimmy Dunn wrote in touregypt.net: The “phyle were named for the different parts of a boat, including the Great (or Starboard), the Asiatic (or Port), the Green (or Prow), the Little (or Stern), and the Last (or Good) Phyle. The name of the fifth phyle is uncertain, but may have referred to the helmsmen's position. It should be noted that even the priesthood was arranged in a similar fashion. These phyle were then divided into four, or later, two smaller groups that also had names , usually related to their geographical origin, or sometimes related to the required skills or virtues of the workers. [Source: Jimmy Dunn, touregypt.net/construction =]

“According to Miroslav Verner, there were apparently, at any one time, no more than three phyle comprising six hundred men, working on the Great Pyramid. However, Lehner seems to believe that an entire crew of 2,000 men would have been employed. While we know of the organization of this work force, we know less about what they actually did. Most Egyptologists believe they were involved with transportation and various other logistical supply work. =

“Verner also tells us that a second type of team system was employed. These workers were divided up according to the cardinal compass points, north, south and west. There was probably a forth team that was not referred to as the eastern team, because east, like left, was considered by ancient Egyptians to be a sinister direction. These four teams made up a "troop", and included the craftsmen and specialized workers on the pyramid construction sites. Unfortunately, there is no real evidence of the number of men making up the troop or the various teams. =

“It is possible, or even probable that these two types of construction teams may have been largely made up of a relatively skilled, permanent royal work force. However, it is clear, given the volume of work required to construct the Great Pyramid, that more workers were needed. These workers were probably helpers, and if slaves were used at all, they would have probably been included in this larger workforce. However, many of these helpers were probably unskilled agricultural workers employed on a seasonal basis during the Nile inundation.” =

The public works program went far beyond the construction of the pyramid itself. Canals were dug to transport the pharaoh and the stones to the site and large scale irrigation programs were launched to grow enough food so large numbers of people were freed up to build the pyramids.

Herodotus's idea of how the Pyramids were built

Teams of workers were comprised of 10 to 20 men. These were organized into larger groups known to archaeologists as phyles and they in turn were organized into large work crews. Each unit had its own supervisors. The layout of the cemeteries near the pyramids gives clues on how the work was organized. At the upper part of the cemetery for the pyramid builders were the people with the highest status: with titles like "director of the draftsmen," “overseer of the masonry," “director of workers” and "inspector of the craftsmen." Units of 40 workers slept in long gallery-like barracks. Each barrack have had its own bakery, dining area and porches with rows of sleeping platforms.

Lehner sees the organization of the pyramid building as critical step in state-building. He told Smithsonian magazine, “I think of the site as something like a giant computer circuit. It's like the state left its huge footprint there and then walked off." He also estimated the city around the pyramid was only occupied a few generations and perhaps only existed while the pyramid were being constructed.

Were the Pyramid Builders Slaves?

Scholars have long suggested that the pyramids were built with slaves labor. This view was suggested by Exodus in the Bible, and the A.D. first century historian Josephus. In an off-the-cuff remark the late Israeli Prime Minister Menacham Begin suggested they were built by Israeli slaves. Most Egyptologists now discount the slave labor theory. Hieroglyphics that show the laborers moving the blocks show no whips, sadistic foremen or other evidence of forced labor.

Scholars now believe that the laborers were peasant farmers and conscripted workers who came from villages and hamlets around Egypt and were hired in rotating shifts of three months or during periods when the annual flooding of the Nile made farming impossible. They worked along side skilled pyramid builders and craftsmen who worked year-round.

Based on the presence of beer and bread and other supplies for the afterlife found in the graves of pyramid builders buried near the pyramids between 2575 B.C. And 2467 B.C. , archaeologists believe that laborers were free men, not slaves, who do what they did out of reverence for the pharaohs and the promise to be buried near the pyramids, A piece of limestone on their graves contained an inscription identifying them as pyramid builders.

The construction of the pyramids required great artistic and architectural skill and a large amount of social organization to achieve. Each pharaoh utilized a great deal of "his country's manpower and wealth to build his tomb and the entire civilization was organized to insure the immortality of it ruler."

Alternating teams of workers had to be rotated in and out and the arrival of goods had to be worked out. Support for the pyramid must have also included facilities for food, ceramics and building materials (gypsum mortar, stone, wood) and metal tools, storage facilities for food, fuel and other supplies, housing for workmen and their families, priests responsible for services in the pyramid temples, and a cemetery for workers who died.

Life of the Pyramid Builders

area around the Pyramids

The pyramid builders are regarded as good examples of Egyptian commoners. They lived in crowded, dirty villages consisting of mud brick houses with thatched roofs, some of which had a bakery in the back room. Men wore loin clothes and women dressed in long sheaths attached above the breasts with a shoulder strap. Children went nude until they were teenagers. In ancient times, Egyptian commoners showed respect to people of superior castes by crawling on their stomachs. The teeth of the non-elite were worn down from eating course bread. They suffered from anaemia and had thick bones, more arthritis (indication of hard work) and more fractures and scars that members of the upper classes.

Dr Joyce Tyldesley, University of Manchester: “To the south of the pyramid town lay an industrial district, a gigantic, cohesive complex divided into blocks or galleries separated by paved streets equipped with drains, and including some workers' housing.” There “Lehner has already discovered a copper-processing plant, two bakeries with enough moulds to make hundreds of bell-shaped loaves, and a fish-processing unit complete with the fragile, dusty remains of thousands of fish. This is food production on a truly massive scale, although as yet Lehner has discovered neither storage facilities nor the warehouses. [Source: Dr Joyce Tyldesley, University of Manchester, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Lehner told National Geographic, "I'm less interested in how the Egyptians built the pyramids than in how the pyramids built Egypt...Imagine yourself as a 15-year-old kid in some rural village of about 200 people in the 27th century B.C. One day the pharaoh's men come. They say, 'You and you, and you.' You get on a boat and sail down the Nile." "Eventually you came around a bend and you see this huge geometric structure, like nothing you've ever known. there are hundreds of people working on it. They put you to work. And someone keeps track of you: your name, your hours, your rations. All this was a profoundly socializing experience . You might go back to your village, but you would never be the same."[Source: David Roberts, National Geographic, January 1995]

Lehner told PBS: “You're rotated into this experience, and you serve in your respective crew, gang, phyles, and divisions, and then you're rotated out, and you go back because you have your own large household to whom you are assigned on a kind of an estate-organized society. You have your own village, maybe you even have your own land that you're responsible for. So you're rotated back, but you're not the same. You have seen the central principle of the first nation-state in our planet's history—the Pyramids, the centralization, this organization. They must have been powerful socializing forces. Anyway, we think that that was the experience of the raw recruits.” [Source: PBS, NOVA, February 4, 1997]

“But there must have been a cadre of very seasoned laborers who really knew how to cut stone so fine that you could join them without getting a razor blade in between. Perhaps they were the stone-cutters and-setters, and the experienced quarry men at the quarry wall. And the people who rotated in and out were those doing all the different raw labor, not only the schlepping of the stone but preparing gypsum.”

See Separate Article: LIFE OF THE PYRAMID BUILDERS africame.factsanddetails.com

Pyramid Workers: A National Workforce?

Hawass believes the pyramid builders were motivated by higher forces. He told National Geographic: “They were proud of their work, yes. It's because they were not just building the tomb of a king. They were building Egypt. It was a national project, and everyone was a participant." Hawass told PBS I come to that... based on the size of the Pyramid project, a government project, the size of the tombs, the cemetery. We know we can excavate the cemetery for hundreds of years — generations after generations can work in the cemetery — and the second is the settlement area. I really believe there were permanent workmen who were working for the king. They were paid by the king. These are the technicians who cut the stones, and there are workmen who move the stones and they come and work in rotation. At the same time there are the people who live near the Pyramids that don't need to live at the Pyramids. They come by early in the morning and they work 14 hours, from sunrise to sunset. [Source: PBS, NOVA, February 4, 1997]

Hawass believes the pyramid builders were motivated by higher forces. He told National Geographic: “They were proud of their work, yes. It's because they were not just building the tomb of a king. They were building Egypt. It was a national project, and everyone was a participant." Hawass told PBS I come to that... based on the size of the Pyramid project, a government project, the size of the tombs, the cemetery. We know we can excavate the cemetery for hundreds of years — generations after generations can work in the cemetery — and the second is the settlement area. I really believe there were permanent workmen who were working for the king. They were paid by the king. These are the technicians who cut the stones, and there are workmen who move the stones and they come and work in rotation. At the same time there are the people who live near the Pyramids that don't need to live at the Pyramids. They come by early in the morning and they work 14 hours, from sunrise to sunset. [Source: PBS, NOVA, February 4, 1997]

The workmen who were involved in building the Great Pyramid were divided into gangs or groups, and each group had a name and an overseer. They wrote the names of the gangs. And you have the names of the gangs of Khufu as "Friends of Khufu. " Because they were the friends of Khufu proves that building the Pyramid was not really something that the Egyptians would push. It's like today. If you go to any village you will understand the system of ancient Egyptians. When you build a dam or a big house, people will come to help you. They will work free for you. The households will send food to feed the workmen. And when they build their houses, you will do the same for them.

That's why the Pyramid was the national project of Egypt, because everyone had to participate in building this Pyramid. By food, by workmen, this way the building of the Pyramid was something that everyone felt the need to participate in. Really it was love — they were not really pushed to do it. When the king took the throne, the people had to be ready to participate in building the Pyramid. And when they finished it, they celebrated. That's why even now in modern Egypt we still do celebrations when we finish any project, because that's exactly what happened in ancient Egypt.

Dr Joyce Tyldesley, University of Manchester: “After comparing DNA samples taken from the workers' bones with samples taken from modern Egyptians, Dr Moamina Kamal of Cairo University Medical School has suggested that Khufu's pyramid was a truly nationwide project, with workers drawn to Giza from all over Egypt. She has discovered no trace of any alien race; human or intergalactic, as suggested in some of the more imaginative 'pyramid theories'. |[Source: Dr Joyce Tyldesley, University of Manchester, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Effectively, it seems, the pyramid served both as a gigantic training project and-deliberately or not-as a source of 'Egyptianisation'. The workers who left their communities of maybe 50 or 100 people, to live in a town of 15,000 or more strangers, returned to the provinces with new skills, a wider outlook and a renewed sense of national unity that balanced the loss of loyalty to local traditions. The use of shifts of workers spread the burden and brought about a thorough redistribution of pharaoh's wealth in the form of rations. |::|

“Almost every family in Egypt was either directly or indirectly involved in pyramid building. The pyramid labourers were clearly not slaves. They may well have been the unwilling victims of the corvée or compulsory labour system, the system that allowed the pharaoh to compel his people to work for three or four month shifts on state projects. If this is the case, we may imagine that they were selected at random from local registers. |::|

“But, in a complete reversal of the story of oppression told by Herodotus, Lehner and Hawass have suggested that the labourers may have been volunteers. Hawass believes that the symbolism of the pyramid was already strong enough to encourage people to volunteer for the supreme national project. Mark Lehner has gone further, comparing pyramid building to American Amish barn raising, which is done on a volunteer basis. He might equally well have compared it to the staffing of archaeological digs, which tend to be manned by enthusiastic, unpaid volunteers supervised by a few paid professionals. |::|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last Updated August 2024