Home | Category: Old and Middle Kingdom (Age of the Pyramids)

OLD KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT

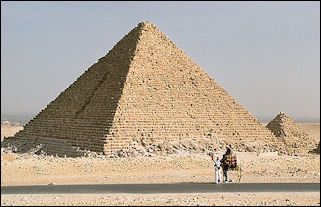

small Pyramid of Menkaure The Old Kingdom (2686 to 2125 B.C. or 2649-2150 B.C.) by most reckonings was comprised of Dynasties 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8, with 25 principal rulers. Before the Old Kingdom was established, ancient Egypt consisted of small regional chiefdoms with separate gods, rulers and government. The greatest achievements in the Old Kingdom took place during the fourth, fifth and sixth dynasties. After the sixth dynasty the central state began to collapse. The main Old Kingdom dynasties were the Fourth Dynasty (2575-2465 B.C.) and the Fifth Dynasty (2465-2323 B.C.). Some also regard the Third Dynasty (2649-2575 B.C.) as a critical period.

As there is with most everything related to ancient Egypt, there is some debate about what the term Old Kingdom means. Some say it is comprised of Dynasties 3, 4, 5, and 6, with 29 principal rulers . Other say it is is comprised of Dynasties 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8, with 25 principal rulers. Others still say it begins with Dynasty 1.Renate Mueller-Wollermann of the University of Tuebingen wrote: “The term “Old Kingdom” was minted in the mid-nineteenth century and at that time meant the period of the 1st through the 16th dynasties; later the term referred to the period of the 1st through the 10th dynasties, and today it refers to the 1st through the 8th dynasties. Some scholars, however, put the end of the Old Kingdom at the end of the 6th Dynasty, or after the reign of Pepy II. Most Egyptologists now designate the first two dynasties as the Early Dynastic Period, the Old Kingdom beginning with the 3rd Dynasty. [Source: Renate, Mueller-Wollermann, University of Tuebingen, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2014, escholarship.org ]

The Old Kingdom and the Middle Kingdom together represent an important single phase in Egyptian political and cultural development. The Third Dynasty reached a level of competence that marked a plateau of achievement for ancient Egypt. After five centuries and following the end of the Sixth Dynasty (ca. 2181 B.C.), the system faltered, and a century and a half of civil war, the First Intermediate Period, ensued. The reestablishment of a powerful central government during the Twelfth Dynasty, however, re-instituted the patterns of the Old Kingdom. Thus, the Old Kingdom and the Middle Kingdom may be considered together. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

Before the Old Kingdom was established, ancient Egypt consisted of small regional chiefdoms with separate gods, rulers and governments. The main Old Kingdom dynasties were: the Third Dynasty of the Old Kingdom. (2649-2575 B.C.); the Fourth Dynasty of Old Kingdom (2575-2465 B.C.); and the Fifth Dynasty of Old Kingdom (2465-2323 B.C.). The greatest achievements in the Old Kingdom took place during the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth dynasties. After the Sixth dynasty the central state began to collapse and the First Intermediate Period transpired. Some scholars used to consider the First Intermediate Period as part of the Old Kingdom Period.

RELATED ARTICLES:

OLD KINGDOM DYNASTIES (3RD THROUGH 6TH) OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

RULERS OF THE OLD KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AGE OF THE PYRAMIDS AND THE PHARAOHS THAT BUILT THEM africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PYRAMIDS OF ANCIENT EGYPT: HISTORY, COMPONENTS AND TYPES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

BUILDING THE PYRAMIDS: RAMPS, ENGINEERING FEATS, MATERIALS AND QUARRYING AND CUTTING THE STONES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PYRAMID BUILDERS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FALL OF THE OLD KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT AND THE FIRST INTERMEDIATE PERIOD (2150-2030 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A History of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2: From the Great Pyramid to the Fall of the Middle Kingdom” by John Romer (2012) Amazon.com;

"In the Shadow of the Pyramids: Egypt during the Old Kingdom" by Jaromir Malek, Many illustrations (1986) Amazon.com;

“Early Dynastic Egypt” by Toby A.H. Wilkinson (2001) Amazon.com;

”Ancient Egypt: Foundations of a Civilization” by Douglas J. Brewer (2005) Amazon.com;

“Death, Power, and Apotheosis in Ancient Egypt: The Old and Middle Kingdoms”

by Julia Troche (2021) Amazon.com;

“Analyzing Collapse: The Rise and Fall of the Old Kingdom” by Miroslav Bárta , Aidan Dodson, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume I: From the Beginnings to Old Kingdom Egypt and the Dynasty of Akkad” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, D. T. Potts, Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

"Towards a New History for the Egyptian Old Kingdom – Perspectives on the Pyramid Age" by Peter Der Manuelian (Author) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Descendants of a Lesser God: Regional Power in Old and Middle Kingdom Egypt”

by Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano (2023) Amazon.com;

"The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders" by Naguib Kanawati and Nigel Strudwick Amazon.com;

"Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms" by Miriam Lichtheim and Antonio Lopriano (2006) Amazon.com;

"Domain of Pharaoh: the Structure and Components of the Economy of Old Kingdom Egypt" by Hratch Papazian Amazon.com;

“When the Pyramids Were Built: Egyptian Art of the Old Kingdom” by Dorothea Arnold (1999) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids” by The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1999) Amazon.com;

"Egypt in the Eastern Mediterranean During the Old Kingdom: an Archaeological Perspective" by Karin N. Sowada and Peter Grave (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com; Wilkinson is a fellow of Clare College at Cambridge University;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt:The Definitive Visual History” by Steven R. Snape (2021) Amazon.com;

Highlights of the Old Kingdom

Sphinx

The Old Kingdom period of Ancient Egypt is when the great pyramids and the Great Sphinx were built. Great achievements and advances were made in a number of fields: administration, astronomy, architecture, painting, sculpture, mass transportation, distribution of food, and sanitation. In many cases Old Kingdom traditions were continued with few alterations by the dynasties that followed. Perhaps one million to a million and a half people lived in Old Kingdom Egypt. The the construction of the first pyramids and the Great Sphinx took place early in the Old Kingdom period. Perhaps one million to a million and a half people lived in the Old Kingdom.

The Old Kingdom formed a central state with a national bureaucracy that supervised construction of canals, monuments and pyramids. An administration system was established to govern a large area that included parts of Nubia. Exactly how the Old Kingdom pharaohs forged a powerful state and unified people through a shared national consciousness — that was strong enough to mobilize the labor and administration necessary to build the pyramids and produce great works of art — is not known.

The Old Kingdom pharaohs periodically moved to new places, perhaps so they could have enough room to construct monuments greater than their predecessors. The capital of the Old Kingdom (2686-2181 B.C.) was in Memphis near present-day Cairo. The first pyramids where built around Saqqara, beginning with the Step Pyramid, built in 2630 B.C. Two generations later the first pyramids were built in Giza.

Memphis — Capital of the Old Kingdom and Gateway to the Pyramids

Memphis was the capital of the Old Kingdom and home to extraordinary funerary monuments, including rock tombs, ornate mastabas, temples and pyramids. According to UNESCO: “Memphis is located in the center of the floodplain of the western side of the Nile. Its fame comes from its being the first Capital of Ancient Egypt. The unrivaled geographic location of Memphis, both commanding the entrance to the Delta while being at the confluence of important trade routes, means that there was no possible alternative capital for any ruler with serious ambition to govern both Upper and Lower Egypt. Traditionally believed to have been founded in 3000 BC as the capital of a politically unified Egypt, Memphis served as the effective administrative capital of the country during the Old Kingdom, then during at least part of the Middle and New Kingdoms (besides Itjtawy and Thebes), the Late Period and again in the Ptolemaic Period (along with the city of Alexandria), until it was eclipsed by the foundation of the Islamic garrison city of Fustat on the Nile and its later development, Al Qahira. As well as the home of kings, and the centre of state administration, Memphis was considered to be a site sacred to the gods. [Source: UNESCO World Heritage Site website =]

map of Memphis, the little pyramids are pyramids and burial sites

“The site contains many archaeological remains, reflecting what life was like in the ancient Egyptian city, which include temples, of which the most important is the Temple of Ptah in Mit Rahina. Ptah was the local god of Memphis, the god of creation and the patron of craftsmanship. Other major religious buildings included the sun temples in Abu Ghurab and Abusir, the temple of the god Apis in Memphis, the Serapeum and the Heb-Sed temple in Saqqara. Being the seat of royal power for over eight dynasties, the city also contained palaces and ruins survive of the palace of Apries overlooking the city. The palaces and temples were surrounded by craftsmen’s workshops, dockyards and arsenals, as well as residential neighbourhoods, traces of which survive. =

“The Necropolis of Memphis, to the north and south of the capital, extends southwards from the Giza plateau, through Zawyet Elarian, Abu Ghurab, Abusir, Mit Rahina and Saqqara, and northwards as far as Dahshur. It contains the first complex monumental stone buildings in Egyptian history, as well as evidence of the development of the royal tombs from the early shape called "mastaba" until it reaches the pyramid shape. More than thirty-eight pyramids include the three pyramids of Giza, of which the Great Pyramid of Khufu is the only surviving wonder of the ancient world and one of the most important monuments in the history of humankind, the pyramids of Abusir, Saqqara and Dahshur and the Great Sphinx. Besides these monumental creations, there are more than nine thousand rock-cut tombs, from different historic periods, ranging from the First to the Thirtieth Dynasty, and extending to the Graeco-Roman Period. The property also includes the remains of many smaller temples and settlements, which are invaluable for understanding ancient Egyptian life in this area. =

“Memphis is associated with the religious beliefs related to the God of the Necropolis "Ptah" who was sanctified by the kings, as well as with outstanding ideas, artistic works and technologies.The ensemble of structures and associated archaeological remains at Memphis, including the archaic necropolis at Saqqara, dating back to formation of Pharaonic civilization, the limestone step pyramid of Djoser, the oldest pyramid to be constructed, the tombs and pyramids that reflect the development of funerary monuments, and the remains of the city, together form an exceptional testimony to the power and organization of the ancient capital of Egypt.” =

Art During the Old Kingdom

A high culture developed early in Ancient Egypt. The Old Kingdom is notable for artistic and intellectual achievements (see Egyptian architecture; Egyptian art; Egyptian religion). From the beginning there was a concept of the divinity or quasi-divinity of the king (pharaoh), which lasted from the time that Egypt was first united (c.3200 B.C.) under one ruler until the ultimate fall of Egypt to the Romans. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Catharine H. Roehrig of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Egypt's Old Kingdom (Dynasties 3–6, ca. 2649–2150 B.C.) was one of the most dynamic periods in the development of Egyptian art. During this period, artists learned to express their culture's worldview, creating for the first time images and forms that endured for generations. [Source: Catharine H. Roehrig Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Architects and masons mastered the techniques necessary to build monumental structures in stone. Sculptors created the earliest portraits of individuals and the first lifesize statues in wood, copper, and stone. They perfected the art of carving intricate relief decoration and, through keen observation of the natural world, produced detailed images of animals, plants, and even landscapes, recording the essential elements of their world for eternity in scenes painted and carved on the walls of temples and tombs. \^/

“These images and structures had two principal functions: to ensure an ordered existence and to defeat death by preserving life into the next world. To these ends, over a period of time, Egyptian artists adopted a limited repertoire of standard types and established a formal artistic canon that would define Egyptian art for more than 3,000 years, while remaining flexible enough to allow for subtle variation and innovation. Although much of their artistic effort was centered on preserving life after death, Egyptians also surrounded themselves with beautiful objects to enhance their lives in this world, producing elegant jewelry, finely carved and inlaid furniture, and cosmetic vessels and implements in a wide variety of materials.” \^/

Study of the Old Kingdom

5th dynasty scribe

Renate Mueller-Wollermann of the University of Tuebingen wrote: “Scholarly research on the Old Kingdom has traditionally relied on textual evidence. Texts have been considered to be more expressive than archaeological finds, because they “speak.” A compilation of ancient Egyptian records was already published by 1933, preceded and followed by several anthologies of translations. Moreover, Egyptian literary texts—especially the “Admonitions,” which describe the world as being turned upside down (i.e., in a chaotic state)—have influenced historians. [Source: Renate, Mueller-Wollermann, University of Tuebingen, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2014, escholarship.org ]

“Only recently a change in methodologies has taken place and archaeological evidence has been given more weight. This is due partly to the fact that archaeology has become increasingly scientific and is no longer confined to “digging for treasures.” Furthermore, new sites continue to be opened up (for example, el- Hawawish and Balat in the Kharga Oasis), adding to our information. Because the preponderance of philological and archaeological evidence derives from Middle and Upper Egypt, research has tended to focus on those regions, such evidence from the Delta having so far been lacking; some exceptions are Mendes, Kom el-Hisn, Buto, and the northeastern Delta.

“Still lacking are safe criteria for dating texts and archaeological material, especially in order to distinguish between material from the end of the Old Kingdom and that of the First Intermediate Period. The dating of tombs and their owners is still much debated; progress has been made in establishing temporal sequences of pottery types, but only rarely can equations be made with absolutely dated finds.”

Primary Sources from the Old Kingdom

Jaromir Malek wrote for the BBC: “The historical period that we call the Old Kingdom (2686-2160 B.C.) was immensely long, lasting as it did for over 500 years. When it began, the unified Egyptian state was only about 300 years old and when it came to an end, the state still had nearly 2,000 years left ahead of it. Remoteness in time is one of the main difficulties we encounter when we look for sources of information about the Old Kingdom. Many simply have not survived. [Source: Jaromir Malek, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Most of our traditional sources of information about the Old Kingdom are those concerned with death and the rituals surrounding death: these include pyramids, tombs and graves, but also statues, reliefs and paintings. Even papyri come mainly from pyramid temples. But this does not mean that death was the Egyptians' only preoccupation. |::|

“There are other reasons why so much of our evidence is based on funeral rites. Egyptian towns and villages were situated in the Nile valley, where old houses were pulled down and new ones built on the same spot, because space was valuable-so little remains of the older buildings. Pyramids and tombs, by contrast, were built on desert margins, where the space was not needed for other buildings, so were left to tell their tale centuries after they were built. Also, while domestic housing was made of sun-dried bricks, pyramids and tombs were built of stone-so their chances of survival were infinitely better.” |::|

About the author: Jaromir Malek studied Egyptology and archaeology at Charles University, Prague. Since 1971 he has been editor of the Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings at the Griffith Institute, Oxford. He has taken part in excavations and epigraphic surveys in Nubia, Abusir, Saqqara and Memphis. He has published several books and a number of specialised papers in Egyptological journals. His books include “Egyptian Art” (London, 1999) and another book on ancient Egyptian art published by Phaidon in 2003. |::|

Chronology of the Old Kingdom

Miroslav Bárta wrote: Our sources for the chronology of the Old Kingdom comprise a mere handful of contemporary written documents, supplemented by radiocarbon dates, some of which have recently been recalibrated by Oxford University. The bulk of historical evidence, deriving primarily from residential cemeteries of the ruling kings and the elite, as well as from provincial sites. [Source: Miroslav Bárta, head of the Czech Institute of Egyptology’s Abusir Mission, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2017]

Renate Mueller-Wollermann of the University of Tuebingen wrote: “The succession of kings in the 6th Dynasty is fairly certain: Tety, Userkara, Pepy I, Merenra I, Pepy II, Merenra II, and Nitocris (who was in fact a king, not a ruling queen, as has long been believed), plus two additional kings. The 8th Dynasty comprises 18 kings, most of them wearing the name Neferkara or variants thereof. [Source: Renate, Mueller-Wollermann, University of Tuebingen, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2014, escholarship.org ]

“The end of the 6th Dynasty has been handed down to us by Manetho. In the Turin Canon we find that the 6th and 8th dynasties are combined. According to this list both dynasties lasted 187 years, six months, and three days. The succession of kings reconstructed by the Turin Canon and the Abydos King List is certain, although the last kings of the 6th Dynasty and most of the kings of the 8th Dynasty are not known by contemporary evidence. The succession and reign length of the kings of the 6th Dynasty reconstructed by the Turin Canon are as follows: Tety: X years; Userkara: X years; Pepy I: 20 years; Nemtiemsaef/Merenra I: 44 years; Pepy II: 90+ years; Nemtiemsaef/Merenra II: one year; Netjerkara: X years. Tety may have reigned about 15 years, Userkara a very short time, perhaps two to four years, and Nemtiemsaef/Merenra I less than ten years. The kings of the 8th Dynasty were ephemeral: all their reigns combined probably lasted about one generation, or 50 years at the most.

“The absolute chronology is more difficult to determine due to the paucity of radiocarbon data and the lack of Sothic data. According to recent radiocarbon data, Tety acceded to the throne around 2340 B.C. and the reign of Pepy II ended around 2170 B.C.. This corresponds more or less with the high chronology proposed by Shaw.”

Annual Records from the Old Kingdom

Jaromir Malek wrote for the BBC: “There was no history writing during the Old Kingdom but there were annals, brief records of important events. These are only incompletely preserved. We also have lists of kings, although they date from later periods, mostly from the New Kingdom, which started about a thousand years after the Old Kingdom ended. The most important among the annals is the so-called Royal Canon of Turin, copied in about 1250 B.C. In the third century B.C., Manetho, a priest from the town of Sebennytos (Samannud) in the Nile delta, wrote a history of Egypt based on ancient records. Unfortunately, his work has survived only in brief excerpts. [Source: Jaromir Malek, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“The Egyptians counted the years of each king's reign, but began again when a new king came to the throne. There are no astronomical dates known from the Old Kingdom, which could have provided us with fixed chronological points. The only way of establishing exactly when each king ruled is by adding up the lengths of the reigns known from the lists of kings (but these are not complete) or from the dates that survive on contemporary monuments (although we cannot be sure that the last year of the reign is recorded). |::|

“Modern scientific techniques, especially radiocarbon dating (based on the changes in the radioactive isotope C14), are helpful, but the margin of error is still too large. Other methods, e.g. that based on astronomical observations reflected in the building of pyramids, have the potential to be useful, but more work is needed before they can be used with confidence.” |::|

Old Kingdom Government and Economy

5th dynasty family

Divine kingship was the most striking feature of Egypt in the Old and Middle Kingdomperiods. The political and economic system of Egypt developed around the concept of a god incarnate who was believed through his magical powers to control the Nile flood for the benefit of the nation. In the form of great religious complexes centered on the pyramid tombs, the cult of the pharaoh, the godking , was given monumental expression of a grandeur unsurpassed in the ancient Near East. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

Central to the Egyptian view of kingship was the concept of maat, loosely translated as justice and truth but meaning more than legal fairness and factual accuracy. It referred to the ideal state of the universe and was personified as the goddess Maat. The king was responsible for its appearance, an obligation that acted as a constraint on the arbitrary exercise of power. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

The pharaoh ruled by divine decree. In the early years, his sons and other close relatives acted as his principal advisers and aides. By the Fourth Dynasty, there was a grand vizier or chief minister, who was at first a prince of royal blood and headed every government department. The country was divided into nomes or districts administered by nomarchs or governors. At first, the nomarchs were royal officials who moved from post to post and had no pretense to independence or local ties. The post of nomarch eventually became hereditary, however, and nomarchs passed their offices to their sons. Hereditary offices and the possession of property turned these officials into a landed gentry. Concurrently, kings began rewarding their courtiers with gifts of tax-exempt land. From the middle of the Fifth Dynasty can be traced the beginnings of a feudal state with an increase in the power of these provincial lords, particularly in Upper Egypt. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

Miroslav Bárta wrote: During the Old Kingdom large portions of Egypt were under a relatively centralized state with a well-structured administrative system. Until the end of the Fourth Dynasty Egypt’s royal family exercised a role of complete authority, exemplified in the monumental construction of pyramids.[Source: Miroslav Bárta, head of the Czech Institute of Egyptology’s Abusir Mission, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2017]

Egypt’s economy in the Old Kingdom was based on the combined workings and resources of the central administration, which certainly was not capable of controlling the entire country, and of private and temple properties, which were largely independent of the state and were steadily growing through royal donations. Both state (royal residence) and temple economies were largely redistributive, collecting and subsequently redistributing resources and products according to needs and requirements. Trade flourished, and the kings of the First Dynasty appear to have sent trading expeditions under military escort to Sinai to obtain copper. Indications show that under the Second dynasty, trade existed with areas as far north as the Black Sea.

People and Life During the Old Kingdom

Jaromir Malek wrote for the BBC: “We know infinitely more about the wealthy people of Egypt than we do about the ordinary people, as almost all the monuments were made for the rich and influential. Houses in which ordinary Egyptians lived have not been preserved, and when most people died they were buried in simple graves with few funerary goods...Few Egyptian towns of the Old Kingdom have been located. Elephantine (an island opposite Aswan, in the region of the first Nile cataract) and Ayin Asil (in the Dakhla Oasis, in the Western Desert) are the notable exceptions. [Source: Jaromir Malek, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“We know little about the temples of local gods. But important texts have been found at the sites of some of these temples, especially at Koptos (modern Qift) and Abydos, both in Upper Egypt. The texts are copies of documents that were originally written on papyrus, and are concerned with the temples' administration, especially endowments and exemptions from taxes and forced labour. One such decree, issued by Pepy II for the temple of the god Min at Koptos, includes the following clause concerning the temple personnel: 'My Majesty does not allow them to be employed in royal cattle pens or on the pastures of cattle or the pastures of donkeys and sheep of the department of herdsmen, or on any duty or forced labour demanded by the royal administration throughout the length of eternity.' “|::|

“Texts concerning expeditions sent outside the Nile valley have been found in Sinai (Wadi Maghara and Wadi Kharit), in the Eastern Desert (Wadi Hammamat), and in Nubia. The aim of these enterprises was to bring back stone for building and for the making of statues, also semi-precious stones (turquoise) and possibly copper. An inscription on a rock at Wadi Maghara, in Sinai, records one such expedition sent there by Pepy II: |'The year of the second occasion of the census of all the great and small cattle of Lower and Upper Egypt... The royal mission which was sent with the god's treasurer Hepy to the terraces of turquoise. There served with him: pilots and quarry-masters Bekenptah and Udjai...' [Here follows a long list of names.]” |::|

Tomb Texts from the Old Kingdom

Jaromir Malek wrote for the BBC: “Practically everything that we know about Egyptian kings derives from their monuments. The Pyramid Texts, which were spells concerning the king's afterlife, began to be inscribed inside Egyptian pyramids from the reign of King Unas, about 2350 B.C. The temples for the king's posthumous cult were decorated with reliefs and contained many statues, all of which give us information about the role of the king in Egyptian society. Scenes that show real events are rare. We must not forget that the purpose of these reliefs was to show an ideal state of affairs, which the king wished to last forever, not the contemporary reality. [Source: Jaromir Malek, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

pyramid texts from Saquara

“Documents written on papyri were found in some pyramid temples, especially at Abusir. They concern such matters as lists of priests on duty, records of offerings brought to the temple, accounts, inventories of temple equipment and passes authorizing access to the temple. Several settlements of priests, and of craftsmen and artists, involved in the running of pyramid temples, have been located, in particular at Giza. |::|

“Representations carved on the walls of tombs include scenes of everyday life on the owner's estates and so show how even ordinary people lived and worked. We must be rather careful when interpreting these scenes and must not take them entirely at face value. They were included in order to play a role in the tomb owner's afterlife, not as an accurate record. |::|

“Sometimes, especially in the later part of the Old Kingdom, the tombs contained biographical texts. Many are just self-praising but others are real records of the tomb owner's achievements. This is how one of them, an official called Weni, described a mission assigned to him by King Merenre of the Sixth Dynasty: 'His Majesty sent me to Hatnub in order to bring a great altar of travertine of Hatnub. I brought this altar down for him in 17 days. After it had been quarried at Hatnub, I had it transported downstream in the barge that I had made for it, a barge of acacia wood of 60 cubits in length and 30 cubits in width. It was built in 17 days and in the third month of summer, when there was no water on sandbanks, it was safely moored at the pyramid of King Merenre.'” |::|

Age of the Pyramids

During the "Old Kingdom" pyramid-building techniques were developed and the pyramids of Giza were built. According to Live Science: Papyri that are still being deciphered suggest that groups of professional workers — sometimes translated as "work gangs" — played a major role in the construction of the pyramids, as well as other structures. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “The earliest known pyramid structure is that of the Pyramid of Meidum. There are two theories as to the pyramids construction. One states that the pyramid was started by Huni, Snefer's predecessor, the other that it was began and ended with Sneferu. Whatever the case, the reign of Sneferu went on to produce two more pyramids after Meidum. Meidum, however, was not always in it's rough state as is seen in the picture at left. As is evidenced by graffiti on the outside of the pyramid, the pyramid survived well into the time of the 18th Dynasty. Meidum still stands as a great attempt, if not a triumph of Egyptian architecture. Other pyramids constructed during the time of the Fourth Dynasty include, the Pyramid of Djeddefre, (created by the son of the Pharaoh Khufu), The Pyramids of Giza, The Sphinx, and many many other tombs, temples and pyramids. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Stepped pyramid of Snefu The reigns from Huni, the last king of the Third Dynasty of the Old Kingdom to Djedefre — Radjedef the son of Khufu, the builder of the Great Pyramid — in the middle of the Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom is regarded by some scholars as the true Age of the Pyramids, a period of great technological and ideological innovation.Richard Bussmman of University College London wrote: "Different from the later Old Kingdom, the pyramids and court cemeteries of this period are located within a radius of seventy kilometers from Maidum in the south up to Dahshur, Giza, and Abu Rawash in the north. This wide geographical spread is typical of the early and mid-4th Dynasty. In the late 4th, 5th, and 6th Dynasties, the court cemeteries cluster around Saqqara and Abusir, closer to where an urban center formed, later called Memphis. The Manethonian copies insert a break before Sneferu, whereas the earlier annalistic tradition does not single out the early 4th Dynasty as a separate period. [Source: Richard Bussmman, University College London, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

“The reigns from Huni to Radjedef date approximately to the mid-third millennium B.C.. However, the annalistic tradition offers conflicting information on the names of kings and the length of their reigns, especially for the 3rd Dynasty. If “year of counting” and “year after counting” refer to a strictly biannual rhythm, the entries in the Turin Royal Canon would contradict the contemporaneous 4th Dynasty evidence derived predominantly from graffiti on pyramid blocks . Absolute dates for the reigns of Huni to Radjedef vary between a “high chronology,” 2637 to 2558 B.C., and a “low chronology,” c. 2550 to 2475 B.C. Radiocarbon dates are in better agreement with the high chronology. Estimations of the length of the early to mid- 4th Dynasty significantly exceeding 100 years have not been proposed so far.”

See Separate Articles: AGE OF THE PYRAMIDS AND THE PHARAOHS THAT BUILT THEM factsanddetails.com ; PYRAMIDS OF ANCIENT EGYPT: HISTORY, COMPONENTS AND TYPES factsanddetails.com; BUILDING THE PYRAMIDS: RAMPS, ENGINEERING FEATS, MATERIALS AND QUARRYING AND CUTTING THE STONES factsanddetails.com

Geographical History of the Age of the Pyramids

Richard Bussmman of University College London wrote: "Geographically, the archaeological and inscriptional evidence of the early 4th Dynasty concentrates on the Memphite cemeteries. The location of Huni’s tomb is unknown. Sneferu built the pyramid at Maidum and the Bent Pyramid and Red Pyramid at Dahshur. The tombs of the 4th Dynasty courtiers and later officials at both sites have recently been reinvestigated. Khufu moved the court cemetery to Giza and buried huge boats next to his pyramid. The burial (?) equipment of Hetepheres, perhaps Khufu’s mother, was found secondarily deposited in a cache and yielded spectacular finds, such as wooden poles of a royal canopy, a bed, and a carrying chair. The pyramid and court cemetery of Radjedef is located at Abu Rawash. When Khafra returned to Giza, he embedded his pyramid and the sphinx in the infrastructure established by Khufu. [Source: Richard Bussmman, University College London, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

red pyramid

"Old Kingdom rock inscriptions flank the expedition route to the Red Sea through the Wadi Hammamat. Some may date to the 4th Dynasty. The inscription with a list of 4th Dynasty kings and princes was probably carved during the Middle Kingdom. Recently, the administrative papyri of an official of Khufu were found at Wadi el-Jarf, an Old Kingdom harbor site at the Red Sea. Seal impressions and inscriptions recording expeditions of Khufu’s officials were also found at a camp in the Western Desert, a resting place on the Abu Ballas trail to sub- Saharan Africa.

"Stone bowls bearing the names of Hetepheres and Khafra were recovered in post-4th Dynasty contexts at Ebla and Byblos together with later material. Similar to stone sherds found at Coptos and Hierakonpolis, both inscribed with the name of Khufu, they may have passed through several hands, during trade and gift exchange, prior to their final deposition.

"Royal penetration into local administration is evident at various sites. A granite fragment of Huni found on Elephantine might belong to the local pyramid attached to an administrative area. The sealing material from Elephantine includes royal names of the 3rd to 6th Dynasties, but none with a name of an early 4th Dynasty king. Seal impressions with names of Sneferu were found in the town area of Hierakonpolis. A small statuette of Khufu came to light in one of the mud-brick buildings within the temple enclosure of Abydos.”

Minoan-Egyptian Relations

The Minoan civilization (c. 3000 – 1400 B.C.) of Crete existed at the same time as the Old Kingdom and Middle Kingdom of Egypt. Stefan Pfeiffer of Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg wrote: “Occupying the island of Crete, the Minoans were skilled sailors who had established hegemony in the Aegean; it was therefore natural that they made contact with neighboring civilizations. With Egypt they established mainly economic relations as far as can be judged by archaeological evidence. First contacts between Crete and Egypt are attested by a fragment of a 1st or 2nd Dynasty Egyptian obsidian vase found in Crete in an EM-II-A stratum, testifying to (indirect?) trading contacts since earliest historical times. [Source: Stefan Pfeiffer, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

Minoan snake goddess

“There were three possible routes by which the Minoans (or their trade goods) could have traveled to Egypt. First, there was the direct passage over 350 miles of open sea, which does not seem very likely. The second option was to sail within sight of the shore along the Levantine coast (and probably trade with the settlements there) to (later) Pelusium. The third, and most likely, passage was to cross the Mediterranean to (later) Cyrene and then sail along the coast to Egypt. The Minoans valued gold, alabaster, ivory, semiprecious stones, and ostrich eggs, but Egyptian stone vessels and scarabs were also found in Crete. Some scholars maintain that Egyptian craftsmen were present on the island, based upon a statuette (14 centimeters high) of an Egyptian goldsmith called User that was found at Knossos; this single example, however, should not be considered as evidence for the migration of Egyptian craftsmen. In addition to these items of Egyptian origin, a certain adaptation of Egyptian styles in Minoan art is apparent. The Minoan artisans used some Egyptian elements eclectically, adjusting or adapting their meaning to new contexts.

“Conversely, Egypt imported Minoan pottery, metal vessels, and jewelry, and probably also wine, olive oil, cosmetics, and timber, as the archaeological record proves. We know that the first Minoan artifacts found in Egypt do not date prior to the time of Amenemhat II (1928 – 1893 B.C.), because from his times Middle-Minoan pottery (so-called Kamares ware) is attested. All in all, Minoan culture had at least some influence in Egypt, as can be judged from Egyptian copies of Kamares ware. Even Minoan textiles seem to have been appreciated by the Egyptian elite, as Aegean textile patterns were copied on the walls of tombs from the reigns of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III.

“The pinnacle of Minoan-Egyptian relations can be dated to the beginning of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty. Having already established good relations with the Hyksos, the Minoans stayed in close contact with a number of Egyptian pharaohs as well, as is proven by Minoan frescoes found in two palaces at Tell el- Dabaa/Avaris in the Nile delta. It was at first assumed that these royal houses were decorated during the rule of the Hyksos kings, but this view has been revised. It is now clear from the stratigraphical evidence that the palaces date to the Thutmosid era. Contemporary with this evidence from Lower Egypt are scenes in seven Theban tombs of 18th- Dynasty high court officials that show Minoan legates from “Keftiu “(as Crete is called in Egyptian texts) bearing tribute. According to some scholars, these scenes bear witness to reciprocity of political contacts rather than formal tribute to a dominant partner. Thus the Minoan frescoes in the Lower Egypt and the pictorial evidence in tombs of almost the same period in Upper Egypt underscore rich cultural, economic, and eventually even political, contacts between Egypt and the Minoan civilization during the 18th Dynasty, just before the time of Akhenaten. This is corroborated by the fact that some Egyptian scribes seem to have known the Minoan language .”

Old Kingdom Archaeology

Jaromir Malek wrote for the BBC: “Some knowledge of Old Kingdom technology and working procedures derives from pictures, but most information must be deduced from the monuments and objects that survive from that time. Certain activities were never shown, for example pyramid building, and written documents concerning such works have not survived. [Source: Jaromir Malek, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Modern scientific methods are now beginning to provide a wealth of information on aspects of the Old Kingdom society-aspects that we have not known much about, until now. The study of pottery has become very useful, especially in the search for chronological clues and trade contacts. The study of botanical (plant) and faunal (animal) remains can show us how people in the Old Kingdom lived-which plants they cultivated, which animals they bred, and what they ate. |::|

“Examination of human remains informs us of the Egyptians' state of health. Research concerning different types of stone and metal can also be very revealing: when we establish from where these materials came, and in what quantities, we can make deductions about trade contacts, expeditions sent to procure these materials, the state of technology, and so on. |::|

“There is no one way of searching for sources of information concerning the Old Kingdom. They are all interconnected, and each has a contribution to make. Egyptologists must be prepared to examine any kind of evidence available, whether it is 'traditional' (archaeological and art historical-based on monuments; or philological-based on inscriptions), or 'non-traditional' (mostly new scientific techniques). They must be scavengers of information, leaving no source of information neglected, and must be constantly searching for new approaches.” |::|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024