Home | Category: Old and Middle Kingdom (Age of the Pyramids)

DYNASTIES OF THE OLD KINGDOM

Harthor Temple, Memphis

The Old Kingdom (2686 to 2125 B.C. or 2649-2150 B.C.) by most reckonings was comprised of Dynasties 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8, with 25 principal rulers. Before the Old Kingdom was established, ancient Egypt consisted of small regional chiefdoms with separate gods, rulers and government. The greatest achievements in the Old Kingdom took place during the fourth, fifth and sixth dynasties. After the sixth dynasty the central state began to collapse. The main Old Kingdom dynasties were the Fourth Dynasty (2575-2465 B.C.) and the Fifth Dynasty (2465-2323 B.C.). Some also regard the Third Dynasty (2649-2575 B.C.) as a critical period.

Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “3rd Dynasty: During the first dynasties, architecture was largely based on mud-brick and organic material, and it was not until Djoser came to the throne around 2700 B.C. that the first large-scale building in stone took place. The first of these structures was in the form of the Step Pyramid at Saqqara, shown here. It was designed by the chancellor Imhotep, who was later worshipped as a god of medicine. |The Step Pyramid and the buildings surrounding it owe much to the forms previously created with traditional materials, but are entirely rendered in stone. As the oldest major stone building in the world, this pyramid remains a pivotal monument. The history of the dynasty itself is little known, with even the names and succession of its kings still debated by Egyptologists. [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, Egyptologist, University of Bristol, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“4th Dynasty: The pyramids at Giza, on the outskirts of modern Cairo, are perhaps the most iconic of all Egyptian monuments, and they mark the high point in the engineering skills first displayed by Imhotep in the previous dynasty. The largest, the Great Pyramid, shown here furthest from the camera, remains the most massive freestanding monument ever raised by humankind. |The 4th Dynasty was the period at which many of the institutions of the state appeared in mature form, and the art of this dynasty became firmly established in the canons that would endure until the end of Egyptian civilisation. |::|

“5th Dynasty: The end of the 4th Dynasty marked the close of the era of great pyramids. Henceforth rather smaller and less well built pyramids would be the norm, such as the one shown here, of Sahure at Abu Sir (c.2450 B.C.). In contrast, the temples that adjoined the pyramids, dedicated to the posthumous wellbeing of the dead pharaoh, were greatly increased in size and splendour, being adorned with beautifully carved reliefs on the walls, and paved with exotic stones.” |::|

RELATED ARTICLES:

OLD KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT (CA. 2649–2150 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com ;

RULERS OF THE OLD KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AGE OF THE PYRAMIDS AND THE PHARAOHS THAT BUILT THEM africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PYRAMIDS OF ANCIENT EGYPT: HISTORY, COMPONENTS AND TYPES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

BUILDING THE PYRAMIDS: RAMPS, ENGINEERING FEATS, MATERIALS AND QUARRYING AND CUTTING THE STONES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PYRAMID BUILDERS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FALL OF THE OLD KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT AND THE FIRST INTERMEDIATE PERIOD (2150-2030 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Early Dynastic Egypt” by Toby A.H. Wilkinson (2001) Amazon.com;

“A History of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2: From the Great Pyramid to the Fall of the Middle Kingdom” by John Romer (2012) Amazon.com;

"In the Shadow of the Pyramids: Egypt during the Old Kingdom" by Jaromir Malek, Many illustrations (1986) Amazon.com;

”Ancient Egypt: Foundations of a Civilization” by Douglas J. Brewer (2005) Amazon.com;

“Analyzing Collapse: The Rise and Fall of the Old Kingdom” by Miroslav Bárta , Aidan Dodson, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume I: From the Beginnings to Old Kingdom Egypt and the Dynasty of Akkad” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, D. T. Potts, Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

"Towards a New History for the Egyptian Old Kingdom – Perspectives on the Pyramid Age" by Peter Der Manuelian (Author) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Descendants of a Lesser God: Regional Power in Old and Middle Kingdom Egypt”

by Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano (2023) Amazon.com;

"The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders" by Naguib Kanawati and Nigel Strudwick Amazon.com;

"Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms" by Miriam Lichtheim and Antonio Lopriano (2006) Amazon.com;

"Domain of Pharaoh: the Structure and Components of the Economy of Old Kingdom Egypt" by Hratch Papazian Amazon.com;

“When the Pyramids Were Built: Egyptian Art of the Old Kingdom” by Dorothea Arnold (1999) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids” by The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1999) Amazon.com;

"Egypt in the Eastern Mediterranean During the Old Kingdom: an Archaeological Perspective" by Karin N. Sowada and Peter Grave (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com; Wilkinson is a fellow of Clare College at Cambridge University;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt:The Definitive Visual History” by Steven R. Snape (2021) Amazon.com;

List of Rulers from the Old Kingdom

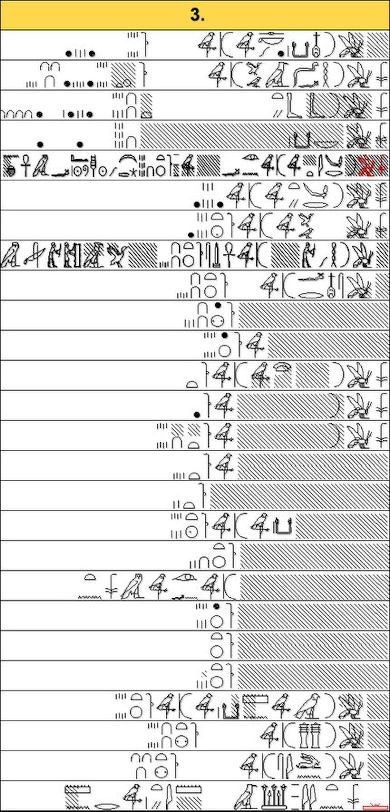

Turin King's List, 3rd Dynasty

Old Kingdom

(ca.2649–2150 B.C.)

Dynasty 3, (ca. 2649–2575 B.C.)

Zanakht (ca. 2649–2630 B.C.)

Djoser (ca. 2630–2611 B.C.)

Sekhemkhet (ca. 2611–2605 B.C.)

Khaba (ca. 2605–2599 B.C.)

Huni (ca. 2599–2575 B.C.)

[Source: Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002]

Dynasty 4, (ca. 2575–2465 B.C.)

Snefru (ca. 2575–2551 B.C.)

Khufu (ca. 2551–2528 B.C.)

Djedefre (ca. 2528–2520 B.C.)

Khafre1 (ca. 2520–2494 B.C.:

Nebka II (ca. 2494–2490 B.C.)

Menkaure2 (ca. 2490–2472 B.C.)

Shepseskaf (ca. 2472–2467 B.C.)

Thamphthis (ca. 2467–2465 B.C.)

Dynasty 5, (ca. 2465–2323 B.C.)

Userkaf (ca. 2465–2458 B.C.)

Sahure (ca. 2458–2446 B.C.:

Neferirkare (ca. 2446–2438 B.C.)

Shepseskare (ca. 2438–2431 B.C.)

Neferefre (ca. 2431–2420 B.C.)

Niuserre (ca. 2420–2389 B.C.)

Menkauhor (ca. 2389–2381 B.C.)

Isesi (ca. 2381–2353 B.C.)

Unis (ca. 2353–2323 B.C.)

Dynasty 6, (ca. 2323–2150 B.C.)

Teti (ca. 2323–2291 B.C.)

Userkare (ca. 2291–2289 B.C.)

Pepi I (ca. 2289–2255 B.C.)

Merenre I (ca. 2255–2246 B.C.)

Pepi II (ca. 2246–2152 B.C.)

Merenre II (ca. 2152–2152 B.C.)

Netjerkare Siptah (ca. 2152–2150 B.C.)

See RULERS OF THE OLD KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Third Dynasty (2686-2613 B.C.)

The Third Dynasty (ca. 2649–2575 B.C.) marks the beginning of the Old Kingdom. The Third Dynasty dynasty was one of the landmarks of Egyptian history, the time during which sun-worship, a new form of religion that later became the religion of the upper classes, was introduced. At the same time mummification and the building of stone monuments began. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

The Third Dynasty was a prosperous and innovative period: when of the worlds first great monumental buildings – the Pyramids — appeared. Djoser, one of the first great kings of Egypt, produced the Step Pyramid at Saqqara, the first large stone building and the precursor of great pyramids of Giza, The kings of this Dynasty were: Sanakht 2686-2667, Djoser 2667-2648, Sekhemkhet 2648-2640 and Huni 2637-2613. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

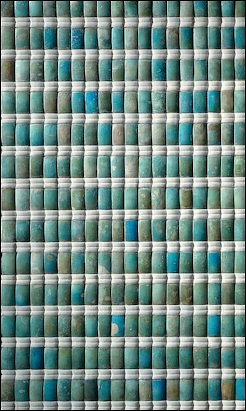

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “The Pharaohs of the Third Dynasty were the first to have actual pyramids constructed as shrines to their deaths. Although crude, these step pyramids were the predecessors to the later Pyramids of Giza and others. The first of these pyramids was designed by Imhotep for Dzoser. Prior to, and during the construction of the step pyramids, rulers were buried in a structure called Mastaba. The Mastaba were non-pyramidal shaped structures which did not contain walls or stone art and closely resembled burial mounds, with long shafts leading down into the tomb area. Sanakhte and Dzoser, the first two Pharaohs of this Dynasty, began exploitation of the Sinai Peninsula, which was rich in turquoise and copper. Little else was done by the kings during this dynasty [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

On the 3rd Dynasty, Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “During the first dynasties, architecture was largely based on mud-brick and organic material, and it was not until Djoser came to the throne around 2700 B.C. that the first large-scale building in stone took place. The first of these structures was in the form of the Step Pyramid at Saqqara, shown here. It was designed by the chancellor Imhotep, who was later worshipped as a god of medicine. |The Step Pyramid and the buildings surrounding it owe much to the forms previously created with traditional materials, but are entirely rendered in stone. As the oldest major stone building in the world, this pyramid remains a pivotal monument. The history of the dynasty itself is little known, with even the names and succession of its kings still debated by Egyptologists.” [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, Egyptologist, University of Bristol, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Fourth Dynasty (2613- 2494 B.C.): Age of the Giza Pyramids

wall tiles from the funerary aprtments of King Djoser

The Fourth Dynasty (2613- 2494 B.C.) is when the Great Pyramids of Giza were built. The Egyptians was able to achieve this extraordinary feat because there was a long period of peace and no threats from outsiders and food was abundant and society was organized so that labor could be put to use building massive things like pyramids. The fourth dynasty originated from Memphis near present-day Cairo while the fifth came from in Elephantine in Upper (southern) Egypt. The transition from one ruling family to another appears to have been peaceful. The kings from the Fourth Dynasty were Sneferu 2613-2589, Khufu 2589-2566, Radjedef 2566-2558, Khafre 2558-2532 (son of Khufu), Menkaura 2532-2503 (grandson of Khufu) and Shepseskaf 2503-2498. The great pyramids were built by Khufu (Cheops), Khafre (Chephren, 2nd biggest) and Menkaura (Mycerinus). [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

In the 4th Dynasty, Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “The pyramids at Giza, on the outskirts of modern Cairo, are perhaps the most iconic of all Egyptian monuments, and they mark the high point in the engineering skills first displayed by Imhotep in the previous dynasty. The largest, the Great Pyramid... remains the most massive freestanding monument ever raised by humankind. |The 4th Dynasty was the period at which many of the institutions of the state appeared in mature form, and the art of this dynasty became firmly established in the canons that would endure until the end of Egyptian civilisation.” [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, Egyptologist, University of Bristol, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Richard Bussmman of University College London wrote: "“The early 4th Dynasty is a true age of pyramids. The pyramids at Maidum, Dahshur, Giza, and Abu Rawash are the biggest ever built in Egypt. Pyramids also served as a template for royal representation in provincial Egypt in the late 3rd to early 4th Dynasty. On a morphological level, the early 4th Dynasty witnessed the emergence of the mortuary temple to the east of the pyramid. The focus of royal funerary culture shifted from the burial itself towards the mortuary cult, a process originating in the Early Dynastic Period. Over time, the royal funerary cult maintained a growing number of priests and became the center of royal representation and economy in the Old Kingdom. [Source: Richard Bussmman, University College London, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

See RULERS OF THE OLD KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Age of the Pyramids

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “The earliest known pyramid structure is that of the Pyramid of Meidum. There are two theories as to the pyramids construction. One states that the pyramid was started by Huni, Snefer's predecessor, the other that it was began and ended with Sneferu. Whatever the case, the reign of Sneferu went on to produce two more pyramids after Meidum. Meidum, however, was not always in it's rough state as is seen in the picture at left. As is evidenced by graffiti on the outside of the pyramid, the pyramid survived well into the time of the 18th Dynasty. Meidum still stands as a great attempt, if not a triumph of Egyptian architecture. Other pyramids constructed during the time of the Fourth Dynasty include, the Pyramid of Djeddefre, (created by the son of the Pharaoh Khufu), The Pyramids of Giza, The Sphinx, and many many other tombs, temples and pyramids. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Stepped pyramid of Snefu The reigns from Huni, the last king of the Third Dynasty of the Old Kingdom to Djedefre — Radjedef the son of Khufu, the builder of the Great Pyramid — in the middle of the Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom is regarded by some scholars as the true Age of the Pyramids, a period of great technological and ideological innovation.Richard Bussmman of University College London wrote: "Different from the later Old Kingdom, the pyramids and court cemeteries of this period are located within a radius of seventy kilometers from Maidum in the south up to Dahshur, Giza, and Abu Rawash in the north. This wide geographical spread is typical of the early and mid-4th Dynasty. In the late 4th, 5th, and 6th Dynasties, the court cemeteries cluster around Saqqara and Abusir, closer to where an urban center formed, later called Memphis. The Manethonian copies insert a break before Sneferu, whereas the earlier annalistic tradition does not single out the early 4th Dynasty as a separate period. [Source: Richard Bussmman, University College London, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

“The reigns from Huni to Radjedef date approximately to the mid-third millennium B.C.. However, the annalistic tradition offers conflicting information on the names of kings and the length of their reigns, especially for the 3rd Dynasty. If “year of counting” and “year after counting” refer to a strictly biannual rhythm, the entries in the Turin Royal Canon would contradict the contemporaneous 4th Dynasty evidence derived predominantly from graffiti on pyramid blocks . Absolute dates for the reigns of Huni to Radjedef vary between a “high chronology,” 2637 to 2558 B.C., and a “low chronology,” c. 2550 to 2475 B.C. Radiocarbon dates are in better agreement with the high chronology. Estimations of the length of the early to mid- 4th Dynasty significantly exceeding 100 years have not been proposed so far.”

See Separate Articles: AGE OF THE PYRAMIDS AND THE PHARAOHS THAT BUILT THEM factsanddetails.com ; PYRAMIDS OF ANCIENT EGYPT: HISTORY, COMPONENTS AND TYPES factsanddetails.com; BUILDING THE PYRAMIDS: RAMPS, ENGINEERING FEATS, MATERIALS AND QUARRYING AND CUTTING THE STONES factsanddetails.com

Features of the Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom

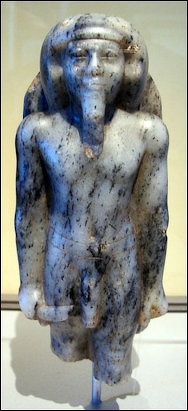

Richard Bussmman of University College London wrote: “Junker famously described the austere style of the early 4th Dynasty court cemeteries as “strenger Stil,” which differed from the more vivid expression of 3rd Dynasty art and architecture. The term implies severity, rigor, and political control. According to Junker, Khufu commanded that elaborate false doors be restricted to “slab stelae,” mounted over the cult place, and statues replaced with “reserve heads”, deposited in front of the subterranean burial chamber, in order to draw the attention of the viewer exclusively to the pyramid, the symbol of the eternal power of the king. Alexanian (1995), Stadelmann (1995), and Flentye (2011) argue that Khufu’s vision was already developed in the reign of Sneferu. Jánosi (2005: 280-283), in contrast, interprets slab stelae as emergency solutions of individuals who died prematurely rather than as a reflection of royal power. [Source: Richard Bussmman, University College London, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

3rd dynasty statue

“The debate resonates modern attitudes towards the period, oscillating between the appreciation of human achievements and the dismissal of total power. Whatever drives their perception, the empirical record certainly contributes to the difficulties. The lack of a broad stream of written sources, other than royal inscriptions and the names and titles of high officials, and the monumentality of pyramids and tombs tend to overshadow the human factor in the evidence and invite for visions of the extreme.

“Following Lehner (2010), the discussion above contextualizes monumentality in questions of social modeling, urbanism, and core-periphery interaction. It is argued that the royal family became the center of a hyperhierarchy at court. Large-scale organization, reflected in settlement and cemetery planning around the court cemeteries, was possible only due to a web of informal structures filling the gaps. The administrative integration of the country was not fully successful because the political center did not understand how the society was organized on a local level. Egyptian kings increased the exploitation of natural resources within the country and maintained interregional trade connections, possibly with the help of military force. Compared to the dense record of later periods, however, the scale and permanency of these activities seems yet limited, even if the royal annals suggest a different scenario.

“Administrative titles of the early 4th Dynasty show that kingship depended on a complex web of people. High courtly titles were typically combined with the title “son of the king” in this period. The majority of high-ranking titles were probably of an honorific nature designed to monitor rivalry at court. Some officials, such as Meten and Neteraperef, were responsible for specific Egyptian provinces, but were buried at court. 4th Dynasty administration is often described as highly centralistic and focused on the royal family. Seal inscriptions reveal that lower ranking officials, who were not members of the royal family, were also instrumental for royal administration already in this period.

“On the level of material culture, the mastaba is the typical type of non-royal tomb during the 4th Dynasty. The idea of rock tombs, so popular among Egyptian elites from the late Old Kingdom onward, is not yet fully established. Petrie coined the term “Maidum bowls” for the red-polished bowls with carinated rim that he discovered at Maidum. They play a key role for dating in the Old Kingdom and have two distinctive shapes in the early 4th Dynasty, one being deep, the other shallow with a flaring rim.”

Fourth Dynasty Building Spree Nearly Bankrupts Ancient Egypt

The Great Pyramids of Giza, the Bent Pyramid at Dashur, the great pyramid complex of Djoser and the necropolis of Saqqara were all built during the Fourth Dynasty. Miroslav Bárta, head of the Czech Institute of Egyptology’s Abusir Mission, told Archaeology magazine that yes the Pyramids and other monuments have been celebrated throughout Egyptian history and have loomed large in the Egyptian historical imagination but they also strained the government and burdened the ancient Egyptian populace. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2020]

According to Archaeology magazine: First built during the 3rd Dynasty near the newly established capital of Memphis, pyramids were symbols of the pharaohs’ unrivaled ability to command vast resources and labor. At least initially, the pyramid-building projects also seem to have contributed to an increasingly sophisticated bureaucracy and the spread of resources throughout the kingdom. “During the construction of the Great Pyramid, I would say that perhaps a quarter of the whole population profited from this single project,” says Bárta. By the end of the 4th Dynasty, though, these incredibly expensive royal constructions came close to bankrupting Egypt.

Even during the 4th Dynasty, the immense stress pyramid building must have placed on the royal treasury began to show. The last pharaoh of the 4th Dynasty chose not to build a pyramid, but was instead buried in a mastaba in Saqqara. This was a considerable downgrade from the Great Pyramid at Giza, which still towers 455 feet above the Nile Valley. By the time the 5th Dynasty began, around 2465 B.C., there must have been general agreement that such ambitious building projects were beyond the pharaoh’s means. The 5th Dynasty pharaohs built significantly smaller pyramids than their predecessors, first in Saqqara and then in Abusir, which freed up resources to construct increasingly sophisticated and richly decorated mortuary temples adjacent to their royal temples.

Fifth Dynasty (2465 – 2325 B.C.)

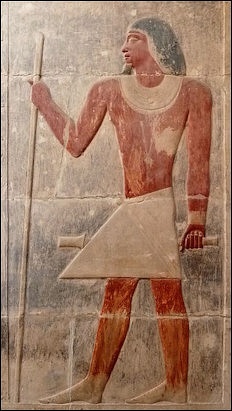

Vizier Kagemni, 5th or 6th dynasty

Fifth Dynasty Kings built smaller pyramid complexes, probably because the larger projects of the Fourth Dynasty had been too expensive and difficult to complete. The pyramids were less solidly constructed than those of the Fourth Dynasty, however carvings from the mortuary temples are well preserved and of the highest quality. Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “The end of the 4th Dynasty marked the close of the era of great pyramids. Henceforth rather smaller and less well built pyramids would be the norm of Sahure at Abu Sir (c.2450 B.C.). In contrast, the temples that adjoined the pyramids, dedicated to the posthumous wellbeing of the dead pharaoh, were greatly increased in size and splendour, being adorned with beautifully carved reliefs on the walls, and paved with exotic stones.” [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, Egyptologist, University of Bristol, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Kings from this period are: Userkaf 2494-2487, Sahura 2487-2475, Neferirkara Kakai 2475-2455, Shepseskara Isi 2455-2448, Raneferef 2448-2445, Nyuserra 2445-2421, Menkauhor 2421-2414, Djedkara Isesi 2414-2375, Unas 2375-2345. The first two kings of the fifth dynasty, were sons of Khentkaues (a woman), who was a member of the Fourth Dynasty royal family. ^^^

According to Archaeology magazine: Discoveries made by Czech teams at Abusir since the 1960s have shown how radical changes instituted during the 5th Dynasty irrevocably impacted the trajectory of Egyptian history. “Abusir tells the story of a time when Egypt changed utterly,” says Bárta. The necropolis of Abusir was the domain of most of the 5th Dynasty pyramids, but it is also densely packed with hundreds of other funeral monuments, including large rectangular tombs known as mastabas that held the remains of non-royal elites and testify to the growing social and political clout of this newly influential group, whose ranks included important priests and scribes. “It’s a story familiar to us today,” says Bárta. “A few families grew powerful and began to control more and more resources.” This new breed of official made their standing clear by commissioning lavish tombs close to those of the pharaohs. “There was a race for status,” says Bárta, one that included the pharaohs themselves, who had to find novel ways to compete with their newly potent subjects. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2020]

The pharaohs of the 5th Dynasty not only inherited a precarious financial and political situation from their predecessors, whose profligate tastes in mortuary practices may have soured large segments of the Egyptian populace on the entire concept of royalty, they also came to power during a period when the climate was becoming increasing unstable. Decreased rainfall seems to have led to droughts, and the subsequent poor harvests threatened both the country’s prosperity and the royal tax revenue, which would have made the pharaohs’ hold on absolute power tenuous. The model that had held sway during earlier dynasties — that of power being invested in a single royal family — was not adequate to the challenges the 5th Dynasty pharaohs faced when they inherited the task of running an increasingly complex government. Suddenly, they found themselves compelled to share authority with a new class of non-royal officials.

The Fifth Dynasty was also a time that witnessed an efflorescence of new styles of art and saw the rise of the cult of Osiris, the god of the dead. The 5th Dynasty pharaohs closely identified themselves with the sun god Ra, and controlled worship of the deity. But veneration of Osiris was not overseen by the pharaohs and was available to all who worshipped the god in the proper manner. Osiris ruled over a netherworld that contained not just the pharaoh’s soul, but the souls of all Egyptians. “We can call this a process of ‘democratization’ or widening participation in sacred affairs,” says Bárta. “It was a new way to balance power.”

See RULERS OF THE OLD KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Fifth Dynasty Government

The Fifth to Seventh dynasties are remarkable for their records of trading expeditions with armed escorts. Although Egypt flourished culturally and commercially during this period, it started to become less centralized and weaker politically. The priests of the sun-god at Heliopolis gained increasing power; the office of provincial rulers became hereditary, and their local influence was thereafter always a threat to the state. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press] [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

The strong centralized government of the god-king that had developed earlier underwent decentralization during the 5th dynasty.A quasi merit system for officials was introduced, allowing people from outside the royal family to be high officials. The vizier no longer had to be a prince, and the nomarchs began to reside in the nome that they administered rather than in the royal residence or capital. The number of nobles, or officials, administering the country expanded and many of their tombs are at Saqqara. Very old papyri from the 5th dynasty survives and they show developed forms of accounting and record keeping existed. Some documents show that goods were redistributed between the royal residence, temples and officials. [Sources: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com; New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003]

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: During the 3rd and 4th Dynasties, political power in Egypt had been centralized in Memphis in the person of the pharaoh and his family members. But from the beginning of the 5th Dynasty, high-, mid-, and even low-level officials seem to have been granted unprecedented levels of authority and income. By the reign of Niuserre, an official named Ty, whose titles included King’s Hairdresser, was buried in a monumental, multiroom, richly decorated complex in Saqqara that was first excavated in the late nineteenth century. Large reliefs in the tomb depict at least 1,800 people, mainly priests, but also farmers, hunters, and other common people going about their daily life and providing services to Ty and his family. The tomb embodies the social changes that were accelerating during Niuserre’s reign. Expensive non-royal tombs and the appearance of family tombs at Abusir during this period show that new networks of power, likened by Bárta to those of nepotistic organized crime families, were beginning to compete with royal authority. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2020]

“A host of smaller, but nonetheless dramatic, monuments in Abusir and Saqqara also chart the changes that transformed Egypt during the 5th Dynasty. Bárta’s colleague Veronika Dulikova has conducted extensive analysis of the names and titles of officials buried in the cemeteries. This has enabled her to partially reconstruct a complicated network of family ties that kept the 5th Dynasty government functioning. These families constituted what Bárta only half-jokingly refers to as “the world’s first deep state.”

“The Czech Mission has recently excavated tombs belonging to one of these powerful extended families in a cemetery at Abusir founded by the chief royal physician Shepseskafankh, who served the pharaoh Neferirkare. Inscriptions in the cemetery show that in many cases successive generations of the family held the same titles. “We can follow a strong tendency towards nepotism during a period when important offices were controlled by the same families,” says Bárta.Another large tomb in the cemetery recently unearthed by the Czech team belonged to Kairsu, a powerful scribe who served under Niuserre. His tomb was built just north of Neferirkare’s pyramid and featured dark basalt blocks in its facade and in an adjacent chapel. This particular material was typically used in royal tombs, and Kairsu’s monument is thus far the only instance of an Old Kingdom non-royal tomb outfitted with these blocks. They may have been intended to serve as metaphors for the rich soil in the Nile Delta, where, according to myth, Osiris was miraculously reborn.

As more non-royal families ascended to power in Memphis, the system of local governorships that existed throughout Egypt also grew in importance. These governorships had largely been figureheads during the reigns of earlier pharaohs, but during the 5th Dynasty, it seems that the people who held these offices actually lived in their designated provinces, instead of ruling them from Memphis, as had previously been the norm.

Solar Temples, Pyramid Texts and Osiris Worship During the Fifth Dynasty

Fifth Dynasty kings explicitly associated themselves with the sun god ra, whose cult was based at Heliopolis (biblical On) in modern Cairo. Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: The dynasty’s founder, Userkaf (r. ca. 2465–2458 B.C.), instituted the practice of building solar temples, elaborate complexes centered around obelisks. These were dedicated to Ra and linked the pharaoh’s authority to the sun god’s supremacy. And there is some evidence in later texts that the 5th Dynasty pharaohs had good reason to cement their legitimacy. A Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.) document known as the Westcar Papyrus suggests the 5th Dynasty rulers may have come at least in part from non-royal origins, making them keen to prove their bona fides as deities on Earth. The story recounted in this document is that the first two 5th Dynasty pharaohs, Userkaf and Sahure (r. ca. 2458–2446 B.C.) were sons of the god Ra. Because their royal lineage isn’t mentioned, some scholars have inferred they were not of royal stock, which would have made their connection to Ra even more important in asserting their powers as gods on Earth. All the kings of the 5th Dynasty but one took regnal names that linked their power to Ra, testifying to their special connection to the god of the sun. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2020]

A total of six solar temples were built during the 5th Dynasty. Offerings for all the royal mortuary complexes were first taken to these temples, where they were “solarized,” or exposed to the sun for a set period of time to absorb its power. The sun temple of the 5th Dynasty pharaoh Niuserre (r. ca. 2420–2389 B.C.) lies just north of the necropolis of Abusir and had extensive storage facilities for these sacred gifts, which could include everything from food to furniture. “Rich and varied offerings flowed from the residence of the king to the solar temples and from there to individual mortuary temples where, after they were symbolically offered on altars, they were used as payments in kind to different ranks of officials,” says Bárta. “In a situation when more and more non-royal officials started to occupy even the highest positions in the state administration, this enabled the king to maintain some control of the country’s resources.”

The reign of Niuserre was the period when Osiris, the lord of the netherworld, was mentioned for the first time. Hieroglyphic inscriptions praising the god have been discovered in the tombs of officials in Abusir and Saqqara. He was first invoked as an important deity in texts discovered in a tomb at Saqqara belonging to an official named Ptahshepses, who served Userkaf and died during the reign of Niuserre. The official’s son, also named Ptahshepses, was Niuserre’s son-in-law. The younger man’s many titles included Privy to the Secret of the House of Morning and Overseer of All Works of the King. He seems to have been the first vizier whose power came close to equaling that of the pharaoh, and his many functions and titles were passed on to his descendants. In fact, his funerary monument in Abusir was more spectacular than the tombs of members of the royal family and rose in pride of place in front of the pyramids of Sahure and Niuserre. No hieroglyphs have been discovered in the tomb of the younger Ptahshepses acclaiming Osiris as the king of the dead, but it is likely that, just as his father had been, he was loyal not only to the pharaoh on Earth, but to the pharaoh in the next world as well.

By end of the 5th Dynasty, the cult of Osiris was in ascendance. The line’s last two kings did not even build solar temples, and the royal cemetery was moved from Abusir back to Saqqara. The final 5th Dynasty pharaoh, Unis (r. ca. 2353–2323 B.C.), was the only pharaoh of his line not to take a regnal name linked to the god Ra, perhaps further illustrating that Osiris had begun to eclipse the sun god in importance.

Unis’ pyramid at Saqqara was also the smallest one ever built during the Old Kingdom, but inside the modest complex was an innovation that would endure for thousands of years. Unis commissioned a series of sacred formulas or spells known as the Pyramid Texts to be carved on the walls of his burial chamber. These include instructions for properly carrying out a funeral and references to the sun that were both codified earlier, perhaps during the 4th Dynasty. But most of the text is devoted to the worship of Osiris. By this time, the god of death had finally become more important than the sun god, upon whose power the earlier 5th Dynasty rulers had relied. Nevertheless, the Pyramid Texts were still intended to reinforce the pharaoh’s legitimacy. “On a symbolic level, the king needed to come up with a new unique form of his extraordinary standing, being a deputy of the gods on Earth,” says Bárta. “The Pyramid Texts were just such a means of achieving this.” Variations of the Pyramid Texts would be included in the tombs of the 6th Dynasty pharaohs, and even in the pyramids of their queens. Within just a few hundred years, the formulas and spells of the Pyramid Texts had spread beyond royal burials, and were inscribed on the coffins of officials throughout Egypt.

Sixth Dynasty (2345 – 2181 B.C.)

We know a fair amount about the Sixth Dynasty (2345 – 2181 B.C.) because many inscriptions from the period have survived to this day. They include records of trading expeditions to the south from the reigns of Pepi I and an interesting letter written by Pepy II. The pyramid of Pepi II at southern Saqqara is the last major monument of the Old Kingdom. The kings from this period were: Teti 2345-2323, Userkara 2323-2321, Pepy I 2321-2287, Merenra 2287-2278, Pepy II 2278-2184, Nitiqret 2184-2181 [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “During this Dynasty, General Weni gave the army an organizational foundation which lasted well into the New Kingdom. This new army was built around a core of veterans which led to the development of a military caste. Weni was the first person,other than the pharaoh, to be depicted in Egyptian Art. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

6th dynasty relief of a hippo

In the Sixth Dynasty ( kings began to appoint officials to serve in provinces throughout Egypt, leading to decentralization of the government. The collapse of the centralized government greatly influenced Egyptian Art and further changed the way in which Egyptians viewed their gods. During prior dynasties, the Pharaoh and his nomarchs had already decided most of the policies of the state. Towards the end of the dynasty, the change of power from the Pharaoh to the nomarchs and other nobles greatly influenced all aspects of Egyptian culture. As a result of such changes, many of the sculptures of the time show the gods and their pharaoh's in a more human light, perhaps suggesting that the gods were more transcendental in the universe than earlier thought.+\

“The role of the pharaoh also seems to be an area of controversy during this era. The pharaoh, Pepi II, in some sculptures, is depicted in stone, as holding most of the tools and markings ascribed to Osirius, as a living god. Most pharaohs near the end of the Sixth Dynasty were represented in such a way. However, Pepi I's statue, suggests a different aspect. Rather than being regarded as a god, the pharaoh takes on the role of a son to the gods, lessening both his power and possibly the ties of the priesthood over the government of the state. +\

See RULERS OF THE OLD KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Foreign Relations During the 6th Dynasty

Politically, the Sixth Dynasty was very active in Egypt and abroad. Copper and turquoise were mined in Sinai, and close commercial connections existed with byblos (Gebal); trading expeditions penetrated into Africa and sailed the Red Sea. Military campaigns in the western and eastern Delta expanded Egyptian territory. Despite such efforts, though, the devolution of power and the long reign (over 90 years) of King Pepi II hastened a collapse of political order. [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003]

Foreign relations during the Old Kingdom were generally peaceful, and foreign expeditions were related either to defense or, more frequently, to trade. A 6th dynasty official named Weni inscribed his autobiography on a wall in his tomb-chapel. He reports that at the behest of the Pharaoh he led five expeditions into the Southern Levant to defend against the "Sand-dwellers" (Lichtheim 18ff.). [Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica, Thomson Gale, 2007]

“During this period, the exploitation of the Sinai Peninsula, which was rich in turquoise and copper, was taking place. Trade outside the Nile Valley began during the reign of Sahure. During the reign of Pepi I the Egyptian army was organized by General Weni and a warrior caste developed. The Old Kingdom came to an end with the death of Pepi II. Following his death, the central government collapsed. This brought about a period of turmoil known as the 1st Intermediate Period.”

At least two stone vessels bearing Old Kingdom royal names have been discovered at Tel Mardikhi, Ebla, in central Syria. There is no certainty as to how the vessels got to Ebla (one, bearing Pepy I's name, is thought to have come through Byblos, and the other with Kephren's name may have come directly from Egypt), but their existence attests to far reaching diplomatic connections between Egypt and the Levant.

Decline of the Old Kingdom During the Sixth Dynasty

Miroslav Bárta wrote: During the Sixth Dynasty the Old Kingdom began to disintegrate. Indications are that the state administration was weakening, and the role and importance of the central government was decreasing, while local centers were becoming more powerful—a fact already acknowledged by most rulers of the Fifth Dynasty—the dominance of provincial officials and their families exhibiting a steady rise. The king’s office as well as his divine status were increasingly compromised as the struggle for power and influence at the royal court gained in importance and currency; indeed court intrigues are reported. [Source: Miroslav Bárta, head of the Czech Institute of Egyptology’s Abusir Mission, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2017]

The state, or rather the ruling king, responded to this development by constantly introducing changes to the administrative system, which yet grew less and less effective. The so-called status race, an omnipresent feature in Egyptian history, became more explicit. Nonetheless, for the duration of the Sixth Dynasty, the backbone of the state’s administration was able to maintain control over most of the country and oversee the running of the mortuary cults and major temple installations. Moreover, the state remained capable of financing and organizing expeditions to the Sinai Peninsula, Hatnub in the Eastern Desert, Syria, Palestine, and the more distant regions of Nubia, though increasing troubles abroad are attested, including explicit attacks on Egyptian expeditions, and even the destruction of sites.

See FALL OF THE OLD KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT AND THE FIRST INTERMEDIATE PERIOD (2150-2030 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024