Home | Category: Old and Middle Kingdom (Age of the Pyramids) / Art and Architecture

PYRAMIDS OF ANCIENT EGYPT

Stepped pyramid at Saqqara Pyramid are royal tombs. Located nearby was a mortuary temple and a valley temple where the king's body was ritually prepared before it was carried on a desert causeway to the pyramid. Even though the pyramids were believed to have been erected for the dead a grave or a royal mummy has never been found inside one. Positioned near the pyramids were “ mastabas” of his nobles.

Dr Joyce Tyldesley of the University of Manchester wrote for the BBC: “Egypt's pyramids served as tombs for her dead kings. The focus of a complex of ritual buildings, the pyramid was the magical powerhouse where the mummified pharaoh would attain eternal life. The first pyramid was Djoser's Step Pyramid, built not long after Egypt had become a unified land. The Great Pyramid of Khufu, at Giza, was raised a century later.” [Source: Dr Joyce Tyldesley, University of Manchester, BBC, February 17, 2011|::|]

The ancient Egyptian pyramids were built between about roughly 2700 B.C. and 1500 B.C. This makes the earliest pyramids about the same age as Stonehenge, which was initially built between 4,000 to 5,000 years ago. According to Wikipedia 118 known pyramids (most of them now ruined) were built in Egypt. All but twelve of them were built for men. The only other ancient structure that is comparable in term of size is the Great Wall of China. Not all pyramids were big though. The pyramid built by Khufu’s son Djedefre measured only 11 meters (35 feet) on each side. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, August 30, 2023]

"Pyramid" is Greek for "wheaten cake," a word coined perhaps because the Greeks thought the pyramids looked like cakes sitting on the desert ("obelisk" is a Greek word that means "skewer" which also suggests that maybe the Greeks didn't get enough to eat when they were in Egypt). The Egyptian word for tomb was a "castle of eternity" and their word for pyramid may have meant "place of accession." The Step Pyramid of Djoser was described as a "staircase to heaven" which the pharaoh "may mount up to heaven thereby." [Source: Daniel Boorstin, "The Creators"]

Large amounts of government money was diverted to build the pyramids and royal tombs. The Pyramids were reserved for royals. The large priest and noblemen class built elaborate house-like stone tombs with detailed stone engravings and hieroglyphics. Traditionally the pharaoh ordered work on his pyramid to begin almost immediately after he took the throne. Work often was completed or wrapped up soon after he died.

It is believed that royal mummies were placed in the pyramid tombs although none have ever been found. Items that have been found in Old Kingdom noblemen tombs include papyrus writing material and things made from gold and lapis lazuli.

RELATED ARTICLES:

AGE OF THE PYRAMIDS AND THE PHARAOHS THAT BUILT THEM africame.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY PYRAMIDS OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PYRAMIDS OF GIZA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

BUILDING THE PYRAMIDS: LAYOUT, ENGINEERING, ALIGNMENT africame.factsanddetails.com

PYRAMID RAMPS AND PUTTING THE STONES IN PLACE africame.factsanddetails.com

BUILDING MATERIALS FOR PYRAMIDS — QUARRYING, CUTTING AND MOVING THE STONES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

STUDY OF THE PYRAMIDS: PYRAMIDOLOGY, SERIOUS SCHOLARSHIP AND PSEUDOSCIENCE africame.factsanddetails.com

PYRAMID BUILDERS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LIFE OF THE PYRAMID BUILDERS africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Complete Pyramids” by Mark Lehner (1997) Amazon.com;

“Giza and the Pyramids: The Definitive History” by Mark Lehner and Zahi Hawass (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Egyptian Pyramids: A Comprehensive, Illustrated Reference” by J.P. Lepre (1990, 2006) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Pyramids and Mastaba Tombs” by Philip J. Watson (2009) Amazon.com;

“How the Great Pyramid Was Built” by Craig B. Smith (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Secret of the Great Pyramid: How One Man's Obsession Led to the Solution of Ancient Egypt's Greatest Mystery”, Illustrated, by Bob Brier, Jean-Pierre Houdin (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Great Pyramid: 2590 BC Onwards - an Insight into the Construction, Meaning and Exploration of the Great Pyramid of Giza” By Franck Monnier, Dr. David Lightbody (2019) Amazon.com;

“ Pyramid (DK Eyewitness Books) by James Putnam (2011) Amazon.com;

”The Pyramid Builder: Cheops, the Man behind the Great Pyramid” by Christine El Mahdy (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt” by A. David (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Builders of the Pyramids” by Zahi Hawass (2009) Amazon.com;

“Mountains of the Pharaohs: The Untold Story of the Pyramid Builders” by Zahi Hawass (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture” by Dieter Arnold (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Construction and Architecture” by Somers Clarke and R. Engelbach (2014) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Architecture in Fifteen Monuments” by Felix Arnold (2022) Amazon.com;

“Building in Egypt” by Dieter Arnold (1991) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Masonry: The Building Craft” by Somers Clarke and R. Engelbach | (2023) Amazon.com;

“Architecture, Astronomy and Sacred Landscape in Ancient Egypt” by Giulio Magli (2013) Amazon.com;

“Architecture and Mathematics in Ancient Egypt” by Corinna Rossi (2004) Amazon.com;

Seven Wonders of the World

The pyramids are the only one of the seven wonders to survive. The others vanished after they were toppled by earthquakes and/or scavenged for building material. The images that we have of the seven wonders today are primarily paintings and drawing made by medieval and Renaissance artists over a thousand years after the wonders were gone.

The Seven Wonders of the World were first mentioned in the 2nd century B.C. by a man called Antipater of Sidon. They are: 1) the Pyramids of Giza (Egypt); 2) Hanging Gardens of Babylon (Iraq); 3) the Tomb of King Mausolus (Turkey); 4) Temple of Diana (Turkey); 5) Colossus of Rhodes (Greece); 6) Statue of Olympia (Greece); 7) The Pharos of Alexandria (Egypt).

How Many Ancient Egyptian Pyramids Are There?

Bent pyramid According to Wikipedia there are 118 pyramids. Of these 54 are large enough to have a substructure. Live Science talked with a number of scholars and found that coming up a definitive number of pyramids can be quite complicated. "I don't think it's an answerable question," Ann Macy Roth, a clinical professor of art history and Hebrew and Judaic studies at New York University, told Live Science. Roth noted that scholars don't necessarily agree on what counts as an Egyptian pyramid. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science February 29, 2024

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: For instance, during the 25th dynasty (circa 712 to 664 B.C.), Egypt was ruled by pharaohs from Nubia (now modern-day Sudan and parts of southern Egypt). These Nubian leaders built pyramids in Sudan but were also rulers of Egypt, so it's a matter of debate whether the pyramids they built in Sudan should be counted. Another problem is whether smaller pyramids — sometimes called "queens' pyramids" — that were located beside larger pyramids should be counted toward the total. For instance, there are at least eight smaller pyramids beside the pyramids of Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure at Giza. Modern day scholars also call these smaller pyramids, which are sometimes poorly preserved, "secondary pyramids. "

Mark Lehner, president of Ancient Egypt Research Associates, pointed out further challenges with counting the pyramids. "It depends in part on what you call a pyramid," Lehner told Live Science. One problem is that not all pyramids were completed. And in some instances, construction of a pyramid stopped shortly after it began, so there's the question of "whether you count pyramids that hardly got started," he said.

Lehner also noted that during the New Kingdom (circa 1550 to 1070 B.C.), private individuals sometimes built a small pyramid at their tomb, and whether to count these tiny pyramids is debated. "If you tried to include the non-royal pyramids of the New Kingdom, which were normally quite small and are often completely ruined, there are many, many examples, and probably many more that have been completely lost, or with foundations not yet excavated," Roth said.

While the number of Egyptian pyramids is debatable, one scholar said that the 118 number may not be far off. "I believe that figure is probably in the right ballpark although I haven't personally counted them all," David Lightbody, an Egyptologist and adjunct professor at the University of Vermont, told Live Science. He noted that many would be smaller private pyramids. While Egypt is well known for its pyramids, there are actually more pyramids in Sudan than in Egypt, Lightbody said. Indeed, vast numbers of pyramids continue to be found in the ancient cemeteries of Sudan although they are much smaller than those constructed at Giza.

Dating the Pyramids

Mark Lehner told PBS: There's no one easy way that we know what the date of the pyramids happens to be. It's mostly by context. The pyramids are surrounded by cemeteries of other tombs. In these tombs we find bodies. Sometimes we find organic materials, like fragments of reed, and wood, wooden coffins. We find the bones of the people who lived and were buried in these tombs. All that can be radiocarbon dated, for example. But primarily we date the pyramids by their position in the development of Egyptian architecture and material culture over the broad sweep of 3,000 years. So we're not dealing with any one foothold of factual knowledge at Giza itself. We're dealing with basically the entirety of Egyptology and Egyptian archaeology. [Source: PBS, NOVA, February 4, 1997]

All the pottery you find at Giza looks like the pottery of the time of Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure, the kings who built these pyramids in what we call the Fourth Dynasty, the Old Kingdom. We study the pottery and how it changes over the broad sweep, some 3,000 years. There are people who are experts in all these different periods of pottery or Egyptian ceramics.

You also have inscriptions that are written inside the tombs, the tombs that are located on the west side of the Great Pyramid for the officials, and the tombs that are located on the east side of the Great Pyramid for the nobles, the family of the King Khufu. And you have this lady, the daughter of Khufu. And this man was the vizier of the king. This one was the inspector of the pyramids, the chief inspector of the pyramids, the wife of the pyramid, the priest of the pyramid. You have the inscriptions and you have pottery dated to Dynasty 4. You have inscriptions that they found of someone who was the overseer of the side of the Pyramid of Khufu. And another one who was the overseer of the west side of the pyramid. You have tombs of the workmen who built the pyramids that we found, with at least 30 titles that have been found on them to connect the Great Pyramid of Khufu to Dynasty 4.

There has been radiocarbon dating, or carbon-14 dating done in Egypt and it's been done on some material from Giza. For example, the great boat that was found just south of the Great Pyramid, which we think belongs to Khufu, that was radiocarbon dated — coming out about 2,600 B.C. We had the idea some years back to radiocarbon date the pyramids directly. And as you say, you need organic material in order to do carbon-14 dating, because all living creatures, every living thing takes in carbon-14 during its lifetime, and stops taking in carbon-14 when it dies. And then the carbon-14 starts breaking down at a regular rate. So in effect, you're counting the carbon-14 in an organic specimen. And by virtue of the rate of disintegration of carbon-14 atoms and the amount of carbon-14 in a sample, you can know how old it is. So how do you date the pyramids, because they're made out of stone and mortar? Well, in the 1980s when I was crawling around on the pyramids, as I used to like to do and still do, I noticed that contrary to what many guides tell people, even the stones of the Great Pyramid of Khufu are put together with great quantities of mortar. We're looking, you see, at the core.

So it occurred to me that if we could take these small samples, we could radiocarbon date them, not with conventional radiocarbon dating so much, but recently there's been a development in carbon-14 dating where they use atomic accelerators to count the disintegration rate of the carbon-14 atoms, atom by atom. So you can date extraordinarily small samples. So we set up a program to do that. And it involved us climbing all over the Old Kingdom pyramids, including the ones at Giza, taking as much in the way of organic samples as we could. We weren't damaging the pyramids, because these are tiny little flecks and it's a very strange experience to be crawling over a monument as big as Khufu's, looking for a bit of charcoal that might be as big as the fingernail on your small finger. We noted, not only the samples of charcoal, sometimes there was reed. Now and then in some of the pyramids we found little bits of wood.

Significance of the Pyramids in Ancient Egypt

The Egyptian believed that any mound or pyramid was a symbol of life. Atum, the god of creation, emerging on a mound from the waters of chaos to create mankind and the universe. Pyramids may have represented rays of the sun, on which the pharaohs could ascend to heaven. "The pyramid itself is an enormous machine," one scholar said, "that helps the king go through the wall of the dead, achieve resurrection, and live forever in the happiness of the gods.”

"Few great advances in human technique have been so sudden and spectacular," historian Daniel Boorstin wrote. "Not until the modern skyscraper in the mid-nineteenth century, four thousand years later, was there another comparable leap in man's ability to make his structures rise above the earth."

To put pyramid building in perspective physicists Kurt Mendelssohn wrote: "There is only one project in the world today which, as far as one can see, offers the possibility of being large enough and useless enough to qualify eventually for the new pyramid. And that is the exploration of outer space...In the end, the results of space exploration are likely to be as ephemeral as the pharaoh accompanying the sun. The effort will be gigantic. No other incentive will be provided that the satisfaction of man to make a name for himself by building a tower that reaches into planetary space. Five thousand years ago the Egyptians, for an equally vague reason, accepted a monstrous sacrifice of sweat and toil.”

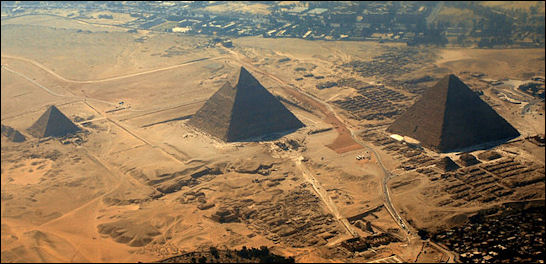

The Pyramids of Giza are the only one of Seven Wonders of the World that survive today. They are huge mausoleums built for three pharaohs in the Old Kingdom — Cheops (father), Chephren (son) and Mycerinus (grandson) — and they once contained the pharaohs mummies. Of the three pyramids Cheops is the largest, Chephren is the second largest, and Mycerinus is considerably smaller than the other two. There are also some small pyramids and some tombs around the main pyramids.

The pyramids are believed to be monuments to the pharaohs’ life force as well as memorials to their lives. Their construction coincided with the development of sun worship in Egypt and its no surprise then that the sun strikes the tops of the pyramids long before it illuminates the dwellings below it. The pyramids may have represented the rays of the sun that the pharaohs used to climb into the heavens.

Pyramids as Mortuary Temples for the Pharaohs

Large amounts of government resources were diverted to build the pyramids and the royal tombs. The Pyramids were reserved for royals. The large priest and noblemen class built elaborate house-like stone tombs with detailed stone engravings and hieroglyphics.

Large amounts of government resources were diverted to build the pyramids and the royal tombs. The Pyramids were reserved for royals. The large priest and noblemen class built elaborate house-like stone tombs with detailed stone engravings and hieroglyphics.

According to PBS: “Each pyramid has a mortuary temple and a valley temple linked by long causeways that were roofed and walled. Alongside Khufu and Khafre's pyramids were large boat-shaped pits and buried boats that were presumably meant to aid the pharaoh's journey to the afterlife.... In addition, cemeteries of royal attendants and relatives surround the three pyramids. The entire plateau is dotted with these tombs, called mastabas, which were built in rectangular bench-like shapes above deep burial shafts.”

The pyramid were manifestations of the Egyptians' beliefs in the afterlife..Early pre-pyramid royal tombs were essentially made up of an underground burial complex in one location-with a large rectangular enclosure a kilometer or so away, where ceremonies for the dead were carried out. The first pyramid, Djoser’s Step Pyramid, which in many ways combined the old separate elements in one location. [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, a Visiting Fellow in the Department of Archaeology at the University of Bristol, where he teaches Egyptology, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Dr Aidan Dodson wrote for BBC: It is important to realise that the actual pyramid was only one part of the overall magical machine that transferred the dead king between the two worlds of the living and the dead. The pyramid complex began on the edge of the desert, where the Valley Building-now lost under a Cairo suburb-formed a monumental portal. |::|

“From here, the burial cortege, priests and visitors would pass through ceremonial halls onto a causeway that ascended the desert escarpment to the mortuary temple, built against the east face of the pyramid. Here, behind a great colonnaded courtyard, lay the sanctuary in which offerings were made to the king's spirit. Either side of the mortuary temple lay a buried boat-perhaps a souvenir of a funeral flotilla, or put there to allow the king to voyage in the heavens-and to the south was a miniature pyramid. Such so-called subsidiary pyramids are of uncertain purpose: they are generally classified as 'ritual'-archaeologists' code for 'obviously important to the ancient people, but we have absolutely no idea why'. |::|

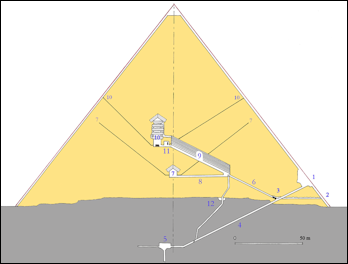

“An offering place was one of the two immutable parts of an Egyptian tomb. The other was the burial place. In the Great Pyramid-and in most other pyramids-this was reached from a narrow, low, opening in the north face. The interior of the Great Pyramid is complex, almost certainly resulting from a number of changes of plan. |::|

“The Great Pyramid was the hub of a huge complex of cemeteries intended for members of the royal court. To the east, three of the king's wives had their own small pyramids, with streets of mastaba-bench-shaped tombs-for his sons and daughters. West of Khufu's pyramid was an even larger cemetery for the great officials of state. All these tombs had been laid out to a single design, a unified architectural conception of the king surrounded by his court, in death as in life. It is a concept that has been without direct parallel before or since.” |::|

Burial Chambers of the Pyramids

On what is inside the Great Pyramid in Giza, Dr Aidan Dodson wrote for BBC:“At first, the burial chamber was to be placed deep underground, with a descending passage and an initial room being carved out of the living rock. It seems, however, that it was decided that a stone sarcophagus-not previously used for kings-should be installed. Such an item would not pass down the descending corridor, and since the pyramid had already risen some distance above its foundations, the only solution was to place a new burial chamber-uniquely-high up in the superstructure, where the sarcophagus could be installed before the chamber walls were built. The architects of later pyramids ensured that there was adequate access to underground chambers by using cut-and-cover techniques rather than tunnelling. [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Two successive intended burial chambers were constructed in the body of the pyramid, the final one lying at the end of an impressive corbel-roofed passage, which seems originally to have been intended simply as a storage-place for the plug-blocks of stone that were made to slide down to block access to the upper chambers after the burial. Corbel-roofing, where each course of the wall blocks are set a little further in than the previous one, allowed passages to be rather wider than would have been felt to be safe with flat ceilings, and are a distinctive feature of the earliest pyramids and tombs of the Fourth Dynasty, to which Khufu belonged. |::|

Cheops Pyramid Interior “The burial took place in that final burial chamber, nowadays dubbed the King's Chamber. An impressive piece of architecture, this granite room was surmounted by a series of 'relieving' chambers that were intended to reduce the weight of masonry pressing down on the ceiling of the burial chamber itself. At the west end of the chamber lay the sarcophagus, now lidless and mutilated. |::|

“It is unclear when the pyramid was first robbed, although some Arab accounts suggest that human remains were found in the sarcophagus early in the ninth century AD. As for what else may have been in the chamber when Khufu was laid to rest, there will have been a canopic chest for his embalmed internal organs, together with furniture and similar items. Examples of such simple, but exquisite, gold-encased items were found in the nearby tomb of Khufu's mother in 1925. |::|

“So-called airshafts, only 20cm (8in) square, leave the north and south walls of the chamber and emerge high up on the corresponding faces of the pyramid. These also were found in the original high-level burial chamber, and seem to have been aimed at particular stars, implying a stellar aspect to the king's afterlife-although as we have seen he was later more closely associated with the sun. Interestingly, the pyramid for Khufu's immediate successor, Djedefre, bore a name that described the king as a 'shining star'.” |::|

Some have said the entrances to the chambers of the pyramids were booby trapped. According to Business Insider: This misconception stems from the discovery of vertical shafts in pyramids that were found to go straight down in the middle of corridors descending to royal chambers. "Some scholars were thinking that these were traps, like the robber would suddenly fall down," Wojciech Ejsmond of the Polish Academy of Sciences said. "Well, such a robber would have needed to be extremely stupid!" he said. [Source: Marianne Guenot, Business Insider, May 5, 2023]

What Was Buried with the Pharaohs Inside the Pyramids?

Did the pharaohs stash lavish grave goods in the pyramid like those found in King Tut’s tomb? The answer is probably no. Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: While the Great Pyramid of Giza and other ancient Egyptian pyramids are incredible monuments, the burial goods inside them were likely relatively modest compared with those buried in the tombs of later pharaohs, such as Tutankhamun. "The burials in the biggest pyramids might have looked quite simple in comparison to Tutankhamun," Wolfram Grajetzki, an honorary senior research fellow at University College London in the U. K. who has studied and written extensively about ancient Egyptian burial customs and burial goods, told Live Science. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, May 22, 2022]

Most pyramids were plundered centuries ago, but a few royal tombs have remained relatively intact and provide clues about their treasures, Grajetzki said. For instance, Princess Neferuptah (who lived around 1800 B.C.) was buried in a pyramid at the site of Hawara, around 60 miles (100 kilometers) south of Cairo. Her burial chamber was excavated in 1956 and "contained pottery, a set of coffins, some gilded personal adornments and a set of royal insignia that identify her with the Underworld god Osiris," Grajetzki said. King Hor (who lived around 1750 B.C.) was buried with a similar set of objects, although he wasn't buried in a pyramid, Grajetzki said. "The body of [Hor] was wrapped in linen, the entrails placed into special containers, called canopic jars," Grajetzki said. "His face was covered with a mummy mask. "

The tomb of Queen Hetepheres, the mother of Khufu (the pharaoh who built the Great Pyramid), is a bit more elaborate. Built at Giza, the tomb had a bed and two chairs that were decorated with gold, along with pottery and miniature copper tools, Grajetzki wrote in an article published in January 2008 in the magazine "Heritage of Egypt. " The substructure (the lower part) of the unfinished pyramid of King Sekhemkhet (circa 2611 B.C. to 2605 B.C.) was found unrobbed at Saqqara, Reg Clark, an Egyptologist who is author of the book "Securing Eternity: Ancient Egyptian Tomb Protection from Prehistory to the Pyramids" (2019), told Live Science. The king's sarcophagus was empty, but archaeologists did find "21 gold bracelets, a golden wand or scepter and various other items of gold jewellery" in a corridor, Clark said. While these are impressive burial goods, they don't come close to the riches found in Tutankhamun's tomb.

The artifacts found in these royal burials suggest that pharaohs entombed in pyramids were probably buried with grave goods that were more modest than those found buried with Tutankhamun, Grajetzki noted. Unlike the early pharaohs, Tutankhamun's tomb was located in the Valley of the Kings — a remote valley near modern-day Luxor that was used as a royal burial site for over 500 years during the New Kingdom, according to Britannica. "This does not mean that he [Khufu] was poorer [than Tutankhamun]. His pyramid proves the opposite. He was just buried following the customs of his day," Grajetzki wrote in the article.

Large treasures haven't been discovered in any of the known Egyptian pyramids. "There were no large 'treasures' in the pyramids, like in the tomb of Tut," Hans-Hubertus Münch, a scholar who has researched and written about ancient Egyptian burial finds, told Live Science. In addition, no tomb containing vast amounts of lavish grave goods has been found dating to earlier times when pyramids were built, Münch said. He noted that during the New Kingdom (circa 1550 B.C. to 1070 B.C.), a time when pyramid building ended, the amount of lavish grave goods buried with royal and non-royal individuals increased.

While the burial goods inside the pyramids were modest compared with later ancient Egyptian tombs, some of the pyramids had lengthy hieroglyphic inscriptions on their walls, which scholars today call the "pyramid texts. " The texts record a large number of "spells" (as Egyptologists call them) and rituals. The pyramid of Unis or Unas (reign circa 2353 B.C. to 2323 B.C.) was the first pyramid to have these texts on its interior walls, while the pyramid of Ibi (reign circa 2109 B.C. to 2107 B.C.) was the last known case, James Allen, an Egyptology professor at Brown University, wrote in the book "The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts" (Society of Biblical Literature, 2005).

The function of the pyramid texts "was to enable the deceased to become an akh," a spirit that exists in the afterlife, Allen wrote. The spells aimed to reunite the "ka" and "ba" — parts of a person's soul that the Egyptians believed were separated at death. The appearance of these texts "probably reflects a shift or innovation in the ancient Egyptians' ideas of the royal afterlife," Allen told Live Science. In earlier times, documents like the Pyramid Texts may have existed, but, for whatever reason, they started being written on the pyramid walls in the time of Unis.

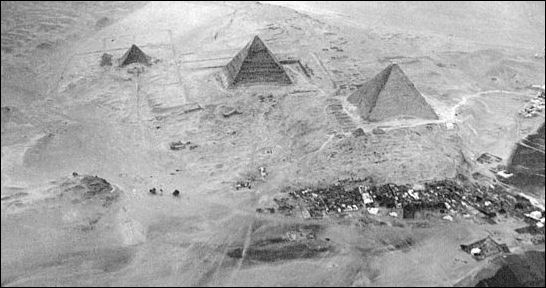

Pyramids of Giza

The Pyramids of Giza are man-made mountains of hewn stone. They are steeper than the pyramids built before them in Saqqara and Danshur because, wrote the scholar Daniel Boorstin, "the pyramid builders had now learned to increase stability by laying the stones of the inner limestone base at a slope...The exact quality of hewn stones inside remains one of the many mysteries. [The] outer structure of huge limestone blocks rests on an inner core of rocks."

Giza complex from a plane

Each pyramid was the focal point of a complex of subsidiary tombs and temples. A high boundary wall surrounded each complex. Only ritually clean priests and officials were allowed to enter. Access from the Nile was provided by a valley temple constructed at the edge of the river plain. During the funeral of a pharaoh buried in Giza, the funeral boat arrived via the river and was carried up a walled causeway to the mortuary temple at the base of the Pyramids, where the body was entombed.

The Pyramids are awe-inspiring for the size and shape and in imagining the labor involved in building them. Some of the best views of the Pyramids and the Sphinx are from barren hills around the plateau. It easy to reach these hills by foot or on the back of a camel or horse. All kinds of organisms live in the Pyramids. They include some foxes living near the top.

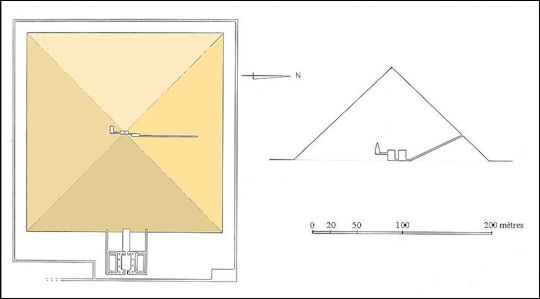

Pyramids of Senusret III in Dahshur: Middle Kingdom Pyramids

Dieter Arnold of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote : “The pyramid field of Dahshur is located along the western desert edge, 30 kilometers south of Cairo. The site includes two huge stone pyramids built by the Dynasty 4 king Snefru and three smaller Dynasty 12 brick pyramids that belonged to Amenemhat II, Senusret III, and Amenemhat III. The five pyramids are separated by vast areas of desert that contain private mastaba tombs and burials, stone quarries, pyramid construction ramps, causeways, workers' settlements, and other installations. [Source: Arnold, Dieter. "The Pyramid Complex of Senusret III in the Cemeteries of Dahshur", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Amenemhet II's son, Senusret, became co-regent with him during the last three years of his reign. He built his pyramid in Dahshur, to the east of the 4th Dynasty pyramids. “King Senusret III (r. 1878–1840 B.C.) was one of the most powerful and important rulers of ancient Egypt. Key developments in religion, political administration, and the arts took place during his reign. He built two funerary complexes, one in Abydos and the other at the north end of the Dahshur pyramid field. Unlike Old Kingdom pyramids, which were constructed entirely of stone, Senusret III's pyramid had a mud-brick core cased with limestone. In ancient times, the valuable limestone was removed by robbers, revealing the soft brick core. As a result of long exposure, the pyramid has now deteriorated to a 21-meter-high mound with a deep crater in the center; originally the pyramid was 62 meters high.\^/ “The Dahshur complex was constructed in two phases. The original complex, which more closely followed Old Kingdom prototypes, included the pyramid, a small pyramid temple to the east, and a stone inner enclosure wall. A second, outer enclosure wall made of brick surrounded six smaller pyramids built for the royal women and a seventh pyramid that served as the king's subsidiary or ka pyramid. Later in the reign of Senusret III, the pyramid complex was enlarged to the north and south, transforming the originally square ground plan into an elongated rectangle. The larger southern extension contained the huge South Temple that seems to have marked the appearance of a new building type in a royal pyramid complex, perhaps replacing or broadening the function of the traditional pyramid temple. \^/

“The plan of Senusret III's apartments under the pyramid closely follows those built by the kings of late Dynasty 5 and Dynasty 6. Senusret III's construction had a long entrance passage, antechamber, crypt, and a room to the side of the antechamber called a serdab by Egyptologists. An unusual feature is the placement of the pyramid entrance, which was not positioned in the north, as was traditional, but in the west. The walls of Senusret III's burial chambers were lined with beautifully finished white limestone, while the crypt was constructed of red granite that was whitewashed. Unlike some Old Kingdom pyramids, the walls were not inscribed with pyramid texts. The crypt contains a finely carved red granite sarcophagus embellished at the base with a pattern that replicates the form of an enclosure wall with palace facade paneling. The absence of any human remains in the tomb, as well as the cleanliness of the interior of the sarcophagus, suggests that Senusret III was not buried in his tomb at Dahshur; instead, the king may have been interred in Abydos, where the king built another mortuary complex. \^/

“The king's pyramid, the burial places of the royal women, and the private tombs surrounding the pyramid complex were plundered during the unstable period of Hyksos rule (ca. 1600 B.C.). The main destruction of the area occurred in the later Ramesside Period (ca. 1295–1186 B.C.), when the pyramids and mastabas were quarried down to their foundations. From the Late Period (712–332 B.C.) onward, the ruined site was used for lower-and middle-class private burials; most of the tombs belong to the late Roman period (ca. 200–350), though Christian burials have also been uncovered. \^/

“The first large-scale excavation of Senusret III's complex was carried out by the French archaeologist Jacques de Morgan (1857–1924) between 1894 and 1895. The Metropolitan Museum resumed excavation work at the site in 1990 and continues its work in yearly, three-month campaigns.” \^/

Books: Arnold, Dieter The Pyramid Complex of Senusret III at Dahshur: Architectural Studies. With contributions and an appendix by Adela Oppenheim and contributions by James P. Allen. Publications of The Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Expedition, vol. 26.. New York: n/a, 2002.

Red Pyramid plans

Pyramids of the Queens and Princesses of Senusret III

Adela Oppenheim of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Flanking the pyramid of Senusret III on the north and south were seven smaller pyramids that primarily belonged to women of the royal family. Beginning with the Dynasty 4 pharaoh Khufu (r. 2551–2528 B.C.), small pyramids for queens and princesses were commonly placed near the pyramid of the king. [Source: Adela Oppenheim, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org\^/]

“The three pyramids to the south of Senusret III's pyramid are earlier and larger than those to the north. The easternmost pyramid of this group probably did not belong to a royal woman, but rather was intended to house the ka, a part of the king's spirit that played an important role in his afterlife. The center pyramid on the south belonged to a Queen Weret I. Inscriptions found around her pyramid, and also at other monuments in Egypt, tell us that she was the mother of a king, presumably Senusret III. No burial chamber was discovered under or near Queen Weret I's pyramid, leading to the conclusion that she was interred elsewhere, perhaps at Lahun near the Faiyum oasis with her presumed husband Senusret II. In this case, Queen Weret I's pyramid at Dahshur would have served as a cenotaph or memorial. The queen mother seems to have played an important role in the king's afterlife. \^/

“The westernmost pyramid on the south side belonged to Queen Weret II, the principal wife of Senusret III. Although her tomb was plundered in antiquity, its entrance remained hidden under the desert sands for centuries until the entrance shaft was found by the Metropolitan Museum excavation in 1994. Queen Weret II's elaborate underground burial complex consists of a shrinelike construction placed under her pyramid and elaborate burial chambers that were actually built beneath the pyramid of the king; the two spaces are connected by a long corridor. Several small objects and pottery that escaped the attention of the tomb robbers were found in her burial chambers. Most surprising was the rare discovery of a cache of the queen's jewelry in a niche at the bottom of the entrance shaft; the unusual placement of the deposit probably led to its being overlooked by the tomb robbers. The objects include two amethyst scarabs inscribed for the pharaoh Amenemhat II, two bracelets with djed-pillar clasps signifying stability, two bracelets with gold lion pendants, a girdle composed of gold cowrie shells, and two anklets with claw pendants. The pieces, now on display in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, represent the sixth major find of royal Middle Kingdom jewelry. On display in the Metropolitan Museum is another jewelry collection that belonged to the Dynasty 12 princess Sit-Hathor-yunet; this group of objects was excavated by the British at Lahun. \^/

“North of Senusret III's pyramid are four smaller pyramids, built later in the king's reign. The second and third from the east belonged respectively to Princess Itakayet and Queen Nefrethenut; the owners of the other two pyramids remain unknown. Burial chambers with stone sarcophagi were placed beneath each of the four pyramids. To the east of the easternmost pyramid, eight royal women were buried in small chambers hollowed out on either side of a common corridor. In this area, Jacques de Morgan (1857–1924) discovered two caches of jewelry on two successive days in 1894. Both treasures are now displayed in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. \^/

“All of the pyramids belonging to royal women had small chapels dedicated to the cult of the deceased; the four north pyramids seem to have had only east chapels, while the two queens' pyramids on the south had north and east chapels. Fragments of relief decoration recovered from these structures indicate that the decorative program consisted mainly of standard offering scenes: processions of offering bearers carrying food approached the queen or princess, who was seated in front of a table. In front of the woman was a large list enumerating the type and quantity of goods she could expect to receive in the afterlife. Additional spaces were filled with representations of piled foodstuffs. The area around the door included scenes of men butchering cattle for meat offerings. Inscriptions above the figures of the women, at the tops of the walls, and above the entrance listed their names and titles.” \^/

New Kingdom Private Pyramids

It is largely thought that the last pyramids were built in the Middle Kingdom (2040–1782 B.C.) and none or hardly any were built in the New Kingdom (1570-1069 B.C.) But that was not the case. While pharaohs stopped building pyramids, wealthy private individuals continued the practice. For example a 3,300 year-old tomb at Abydos, which was built for a scribe named Horemheb, had a 23-foot-high (7 meters) pyramid at its entrance, archaeologists announced in 2014. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, November 26, 2021

Nikhil Swaminathan wrote in Archaeology magazine in 2013: Belgian archaeologists uncovered a mudbrick structure on a hill at Thebes (modern Luxor) that is actually the base of a pyramid erected for a top minister of 19th Dynasty pharaoh Ramses II, who ruled Egypt from 1279 to 1213 B.C. Bricks from it are stamped with a rectangular hieroglyphic inscription,“Osiris, the vizier of Upper and Lower Egypt, Khay. ” [Source: Nikhil Swaminathan, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2013]

The minister, Khay, who is buried in a tomb beneath the pyramid, can be seen in the structure’s capstone, which pays respect to Re-Horakhty, a combination of the sun god Re and sky god Horus. The pyramid would have measured 13 meters (40 feet) along each side, stood roughly 16 meters (50 feet) tall, and overlooked Ramses II’s funerary temple.

Why Did Ancient Egyptian Pharaohs Stop Building Pyramids?

The last known royal pyramid in Egypt was built under King Ahmose I (r 1550 to 1525 B.C.) at Abydos at the very beginning of the New Kingdom. After that the pharaohs were buried in the Valley of the Kings near the ancient Egyptian capital of Thebes (Luxor). The Theban Mapping Project said that the earliest confirmed royal tomb in the valley was built by Thutmose I (reign 1504 to 1492 B.C.). His predecessor Amenhotep I (reign 1525 to 1504 B.C.) may also have had his tomb built in the Valley of the Kings, although this is a matter of debate among Egyptologists. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, November 26, 2021

It's not entirely clear why pharaohs stopped building royal pyramids, and opted instead for the Valley of the Kings, but security concerns could have been a factor. "There are plenty of theories, but since pyramids were inevitably plundered, hiding the royal burials away in a distant valley, carved into the rock and presumably with plenty of necropolis guards, surely played a role," Peter Der Manuelian, an Egyptology professor at Harvard University, told Live Science. "Even before they gave up on pyramids for kings, they had stopped placing the burial chamber under the pyramid. The last king's pyramid — that of Ahmose I, at Abydos — had its burial chamber over 0.5 kilometers [1,640 feet] away, behind it, deeper in the desert," Aidan Dodson, an Egyptology professor at the University of Bristol, told Live Science.

Own Jarus wrote in Live Science: One historical record that may hold important clues was written by a man named "Ineni," who was in charge of building the tomb of Thutmose I in the Valley of the Kings. Ineni wrote that "I supervised the excavation of the cliff tomb of his majesty alone — no one seeing, no one hearing. " This record "obviously suggests that secrecy was a major consideration," Ann Macy Roth, a clinical professor of art history and Hebrew and Judaic studies at New York University, told Live Science.

The natural topography of the Valley of the Kings could explain why it emerged as a favored location for royal tombs. It has a peak now known as el-Qurn (sometimes spelled Gurn), which looks a bit like a pyramid. The peak "closely resembles a pyramid, [so] in a way all royal tombs built in the valley were placed beneath a pyramid," Miroslav Bárta, an Egyptologist who is vice rector of Charles University in the Czech Republic, told Live Science.

For Egyptian pharaohs the pyramid was important as it was a place "of ascension and transformation" to the afterlife, wrote Mark Lehner.in his book "The Complete Pyramids: Solving the Ancient Mysteries". The topography of Luxor, which became the capital of Egypt during the New Kingdom (1550 to 1070 B.C.) may also have played a role in the decline of pyramid construction. The area is "far too restricted in space, with also lots of lumps and bumps," Dodson said. In other words, the ancient capital may have been too small and architecturally challenging to serve as the home for new pyramids.

Religious changes that emphasized building tombs underground are another possible reason the Egyptians ditched grand pyramids. "During the New Kingdom, a concept of the night journey of the king through the Netherworld became extremely popular, and this required sophisticated plans of the tombs hewn in bedrock below ground," Bárta said. The underground tombs hewn into the Valley of the Kings fit this concept well.

Nubian Pyramids

There are more pyramids in Sudan than in Egypt. Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: Pyramids clearly fascinated the Nubian kings and Egypt’s influence on their own cultural practices was long-lasting. As ongoing archaeological work shows, the inhabitants of Nubia, particularly those in the kingdom of Meroe, found a way to imitate Egypt’s monuments. Even so not much is left of many Nubian pyramids. The Nubians primarily built the structures from mud brick. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2013]

At the royal cemetery at Meroe there are about 80 pyramids, some up to 100 feet tall. Since a French explorer first described the cemetery at Meroe in the early nineteenth century, archaeologists have identified the remains of more than 220 royal pyramids in Sudan. Excavations show that early in the Meroitic period (ca. 300 B.C.–A.D. 350), pyramids were built exclusively for those of noble blood. “It would have been sacrilege to erect a pyramid for a nonroyal person,” says Francigny. But later in the kingdom’s history the taboo was relaxed somewhat, and a few wealthy people were allowed to erect monuments for themselves. But their pyramids never rivaled the royals’ in size. Royal or not, Nubians would have viewed the pyramids much as the ancient Egyptians did. For the pharaohs, pyramids were symbols of the, their massive, steep sides representing the angle of the sun’s rays reaching earth. The people of Meroe elaborated on this theme by adding capstones to their pyramids shaped in classic Egyptian forms, such as birds or lotuses emerging from solar discs.

See Separate Article: CULTURE OF THE ANCIENT NUBIANS: ART, TOMBS AND PYRAMIDS africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024