Home | Category: Desert Animals

GOLDEN HAMSTERS

Golden hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) are also called or Syrian hamsters. They are the species that have traditionally been pet hamsters. They are native to an arid region of northern Syria and southern Turkey. Their numbers in the wild have declining so much due to a loss of habitat from agriculture and deliberate elimination by humans because they are considered agricultural pests that they are now considered endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). However, captive breeding of golden hamsters is very common mainly to supply the pet and scientific research animal trade. [Source: Wikipedia]

Golden hamsters have relatively short life spans, 1.5 to two years on average. They can live nearly twice as long in captivity as in the wild. They are up to five times larger than many of the dwarf hamsters kept as pocket Wild European hamster exceeds golden hamsters in size. Many domestic varieties of golden hamsters have been developed for the pet trade.

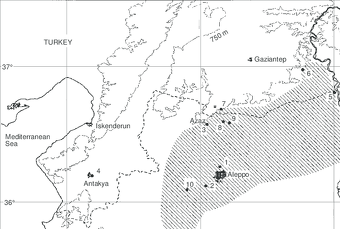

Golden hamsters are perhaps more common as research animals than pets. In the wild, most live on the Aleppinian plateau around Allepo in Syria. They have also been reported in areas of Eastern Turkey. Historically, golden hamsters probably inhabited open steppe habitat, which once characterized the Aleppinian plateau and adjacent areas. As their range has become increasingly populated and taken over by agriculture and urbanization, golden hamsters have transitioned into cultivated areas. Their burrows are often found in legume plots or near irrigation wells. The climate of the region they inhabit can get very hot in the summer. Winters are mildish cold and relatively wet. Overall, precipitation is very low. [Source: Alex Champagne, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Golden hamsters are considered ideal research animals because of their short gestation period, ability to spontaneously ovulate and parts of their physiology is similar enough to humans. Many studies have been conducted in which hamsters were the test subjects. By the same token they are considered to be such destructive agricultural pests in some places the government of Syria has supplied rat poison to farmers in hopes of controlling them.

Golden hamsters are preyed upon a number of animals including foxes, mustelids (weasels and their relativels), owls, birds of prey and snakes. Golden hamsters avoid predator by seeking shelter in their burrows and being vigilant. Their rapid reproductive rate means that golden hamster populations can withstand relatively high rates of predation.

RELATED ARTICLES:

HAMSTERS: TAXONOMY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

HAMSTER SPECIES IN EURASIA: EUROPEANS, ROBOROVSKIS, CAMPBELL'S DWARVES factsanddetails.com

MOUSE-LIKE HAMSTERS: CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES, BEHAVIOR, AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

GERBILS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

GERBIL SPECIES IN ASIA: MONGOLIAN, GREAT, INDIAN factsanddetails.com

GERBILS OF THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA africame.factsanddetails.com

JIRDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES AND REPRODUCTION africame.factsanddetails.com

JERBOAS OF CENTRAL ASIA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

JERBOAS OF THE MIDEAST AND NORTH AFRICA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES africame.factsanddetails.com

EGYPTIAN JERBOAS: GREATER, LESSER, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR africame.factsanddetails.com

PYGMY JERBOAS (WORLD'S SMALLEST RODENTS): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

Golden Hamster Characteristics and Diet

Golden hamsters are medium-sized hamsters. They range in weight from 100 to 125 grams (3.52 to 4.41 ounces) and have a head and body length ranging from 13 to 13.5 centimeters (5.12 to 5.31 inches). Their average basal metabolic rate is 0.69 watts. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not present: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar.[Source: Alex Champagne, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Golden hamsters are significantly smaller than European hamsters and larger than Roborovski hamsters of China and Mongolia. As is the case with many hamsters, golden hamsters have a blunt rostrum (hard, beak-like structures projecting out from the head or mouth), relatively small eyes, large ears, and a short (1.5 centimeters) tail. The fur is golden-brown above, fading to gray or white on the ventral surface. Some individuals may also possess a dark forehead patch and a black stripe on each side of the face running from the cheek to the neck.

Breeding of captive and pet hamsters has resulted in various kings of coat colors and patterns, including white, cream, blonde, cinnamon, black, tortoiseshell, three different shades of gray, dominant spot, banded, and dilute. Selective breeding has also produced a variety of coat types such as long-haired, satin, and rex. [Source:

Golden hamsters are omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals), They feed on seeds, grans, nuts, and insects, including ants, flies cockroaches, and wasps. Like most members of the hamster subfamily, golden hamsters have expandable cheek pouches, which extend from their cheeks to their shoulders. In the wild, hamsters are larder hoarders, meaning they use their cheek pouches to transport food to their burrows. Their name in the local Arabic dialect where they were found roughly translates to "mister saddlebags", due to the amount of storage space in their cheek pouches.

Golden Hamster Behavior

Golden hamsters are terricolous (live on the ground), fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), territorial (defend an area within the home range), and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates).[Source: Alex Champagne, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Golden hamsters are solitary, highly territorial, and very aggressive toward members of their own species except when mating. They spend the day in their burrows, and wake at dusk, and spend much of the night gathering food, which they cache in their burrows. Over the course of a single evening, a single hamster may cover 13 kilometers (eight miles) mainly by going back and forth between foraging areas sources and their burrow. In the winter, golden hamsters experience a period of torpor that is not considered true hibernation. Torpor has been induced in captive animals exposed to temperatures below 8̊C.

Golden hamster burrows have an entrance that leads into a 18-to-45 centimeter (7-to-17 inch) -long vertical tunnel, or "gravity pipe", that descends into a horizontal nest chamber. Usually only a single adult occupies a burrow. Nest chambers are up to 20 centimeters wide and contain a spherical nest made opportunistically out of dry material found in the environment. Urination is restricted a 10-to-15 centimeters (four-to-six inch) dead-end tunnel, while defecation occurs throughout the entire underground structure. Food storage occurs in multiple tunnels that measure between one and one and half meters (3.3 to 5 feet) that run at varying angles from the nest chamber. Golden hamsters maintain a large distance between their home burrows and other of other golden hamsters. The closest measurement between occupied golden hamster burrows in the wild was 118 meters.

Golden Hamster Senses and Communication

Golden hamsters sense using vision, sound, touch, ultrasound and chemicals usually detected with smelling or smelling-like senses. A study with golden hamster showned that vision was used primarily while foraging for seeds and hunting insects. Sound and smell were used less but in the absence of vision, sound was sued more than smell. [Source:Alex Champagne, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Golden hamsters communicate with vision, sound and scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them. To mark their territory, hamsters use scent glands on their flanks, which they rub against objects to spread their scent. A great deal of information can be discerned from flank markings, including kin recognition.

Alex Champagne wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Golden hamsters communicate mainly by scent marking, but they also employ a variety of auditory signals. They produce squeaking sounds in several situations, usually in association with sudden body movements. In addition, hamsters exhibit teeth chattering. Teeth chattering behavior is a sign of aggression. It has been recorded in 92 percent of male to male interactions observed, in 39 percent of female to female interactions, and in only five percent of male to female encounters. Young hamsters are able to produce ultrasonic squeaks that likely are important in maternal care of the young.

Hamsters also rely on visual signals in communicating with members of their own species. In interactions between dominant and submissive individuals, the submissive individual will arch its back and lift its tail. The dominant individual will then mount the subordinate to assert dominance. In male to female interactions, the female will signal that she is ready to mate by taking a quick series of short steps, and assuming a posture in which the body is stretched out, the back legs are splayed, and the tail is up. This posture is referred to as the Lordosis posture. The female may remain in this position for up to 10 minutes. The male will follow the female and sniff and lick her genital region, likely to gather chemical signals. There has additionally been some speculation that the fur of an individual hamster has a bearing on its social status. However, studies have had contradictory results./=\

Golden Hamster Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Golden hamsters in the wild are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time). They engage in seasonal breeding, generally breeding when the daylight hours are long. The average gestation period is only 16 days — the shortest period among non-marsupial mammals — and females can give birth every month or so during the breeding season. The number of offspring ranges from four to 15, with the average number being nine. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. During the pre-weaning stage provisioning and protecting are done by females. The average weaning age is 19-21 days, with independence occurring on average at one month. On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 26-30 days and males do so at 42-48 days. [Source: Alex Champagne, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Ovulation in mature female golden hamsters is mainly determined by the amount of daylight. Ovulation is triggered by more than 12.5 hours) and continues indefinitely as long as the daylight is more than 12.5 hours If the amount of light is reduced, or if females are exposed to complete darkness in a lab setting, they stop ovulating. However, after five months, females acclimate to this shorter photoperiod (amount of daylight) and begin ovulating spontaneously. In the wild, this photoperiodic cycle ensures that young are born during the season most favorable for their survival.

Sexually mature female hamsters come into heat (estrus) every four days. They indicate their receptiveness to males primarly through smell via vaginal secretions. When a female is ready to mate, she increases the number of vaginal marking by pressing her vaginal region against a surface and moving forward a few inches and doing it again. The average amount of time spent giving birth is 1.5 to 2.5 hours. Young are born with their eyes closed. They first open their eyes at 12 to 14 days of age.

Female hamsters enter estrus almost immediately after giving birth, and can become pregnant despite already having a litter. But this puts stress on the mother's body and often results in very weak and undernourished young. In some situations, the mother may reduce the size of her litter through cannibalism. In the wild, this is likely a strategy employed in times of limited resources. In captivity, cannibalism is often a response to some sort of human disturbance. If a mother hamster is inexperienced or feels threatened, she may abandon or eat her young. This happened when gold hamsters were first discovered in 1930.

Discovery of Golden Hamsters

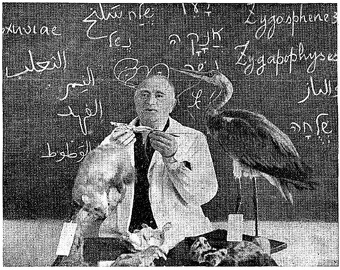

The transformation of wild hamsters into popular pocket pets began in 1930, when a biologist named Israel Aharoni (1882–1946) captured some wild Syrian hamsters in Syria and bred them in Jerusalem for research. Aharoni worked in the Ottoman Empire and British Palestine and is widely known as the "first Hebrew zoologist." He collected a litter of Syrian hamsters on an expedition to Aleppo, Syria. The hamsters were bred as laboratory animals in Jerusalem, but some escaped through a hole in the floor. The majority of domestic golden hamsters are said to be descended from this one litter.

Ben Crair wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “ In the spring of 1930, Aharoni staged an expedition to the hills of Syria, near Aleppo, one of the oldest cities in the world. His quest was simple: he wanted to catch the rare golden mammal whose Arabic name translates roughly as “mister saddlebags.” One of Aharoni’s colleagues, Saul Adler, thought that the animal might be similar enough to humans to serve as a lab animal in medical research, particularly for the study of the parasitic disease leishmaniasis, which was and still is common in the region. [Source: Rob Dunn, Smithsonian magazine, March 24, 2011]

Helping Aharoni on his odyssey was a local hunter named Georius Khalil Tah’an. He had seen Mr. Saddlebags before and would lead Aharoni to where it might be found again. Aharoni instructed Tah’an to ask any people they met along the way if they had seen the golden animal. Tah’an, like many paid guides to explorers, probably thought the mission ridiculous. But he obliged, one house at a time, day after day, in the quest for the animal with the silly name.

On April 12, 1930, fortune struck. Through a series of conversations, the men found a farm where the animal had been seen. Ecstatic, Aharoni, Tah’an and several laborers supplied by the local sheik followed the farmer to his fields. Tah’an and some villagers began to dig excitedly, eagerly, without regard for the farmer, who looked on in dismay at the dirt piling up on top of his young, green shafts of wheat. They dug eight feet down. Then from the dust of the earth they found a nest and in it, the animals. They were golden, furry and tiny—Mr. Saddlebags! Aharoni had found a mother and her pups, ten soft and young. Aharoni removed the animals from the farm and gave them the Hebrew name, oger. We now know them, in English, as the Syrian hamster or, because it is now the most common hamster in the world, simply the hamster.

Breeding the First Domesticated Hamsters

Ben Crair wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The Syrian hamsters Aharoni collected were the first to be studied in any great detail. But he wanted to do more than study them; he wanted to breed them so that hamsters could be used as laboratory animals. Another species of hamster was already being used for research in China, but they would not reproduce in captivity and so had to be collected again and again. Aharoni thought he would be luckier with the Syrian hamster, though just why he was so optimistic is unknown. [Source: Rob Dunn, Smithsonian magazine, March 24, 2011]

Aharoni took the hamsters back to his lab in Jerusalem. Or at least he took some of them. In the wheat field, the mother, upon being placed in a box, began to eat her babies. As Aharoni wrote in his memoir, “I saw the [mother] hamster harden her heart and sever with ugly cruelty the head of the pup that approached her most closely.” Tah’an responded by putting the mother in a cyanide jar to kill her so that she would not eat any more of the babies. In retrospect, killing the mother may have been imprudent because it left the infants alone, too small to feed themselves. Aharoni began with 11 hamsters, and just 9 made it back to Jerusalem, each of them defenseless. Their eyes were still closed.

The babies, fed with an eye-dropper, did well for a while, maybe too well. One night, when the mood around the lab had grown hopeful, five hamsters grew bold, chewed their way out of their wooden cage and were never found. Hein Ben-Menachen, Aharoni’s colleague who was caring for the hamsters, was overwhelmed by the incident. In Aharoni’s words, he was “aghast… smitten, shaken to the depths. . .” These hamsters were serious business.

Four hamsters remained. Then one of the male hamsters ate a female and so there were just three—two females and one suddenly large male. The odds were getting worse by the day, but Ben-Menachen, shamed but determined, would try. He separated the hamsters and made a special chamber filled with hay for the hamsters to breed in. He put a single female in the chamber and then—after she had found a quiet spot among the hay—introduced her only surviving brother. The brother chased his sister around and caught up with her. What happened next Ben-Menachen credited to God, who “nudged a single wheel of the uncountable wheels of nature—and a miracle happened”: the brother and sister hamsters mated.

Popularization of Hamsters as Pets and Research Animals

Hamsters became popular pets after World War II, primarily due to the domestication of the golden hamsters. The process involved scientific research, breeding programs, and later, commercial pet trade. Ben Crair wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Today, Syrian hamsters are nearly everywhere. A precise count is impossible. They are in classrooms, bedrooms and, as Aharoni envisioned, research labs. They scurry under refrigerators. They log thousands of collective miles on hamster wheels. [Source: Rob Dunn, Smithsonian magazine, March 24, 2011]

After the early setbacks Aharoni hamsters “would be fruitful and multiply. That single brother and sister gave rise to 150 offspring who begat even more until there were thousands and then tens of thousands, and finally the modern multitudes of hamsters. These hamsters colonized the world, one cage at a time. Some hamsters were smuggled out of Jerusalem in coat pockets. Others made it out in more conventional ways, in cages or packing boxes. They spread like the children of the first people from the Torah, Adam and Eve. And so it is that every domestic Syrian hamster on earth now descends from Aharoni’s first couple.

Hundreds, maybe thousands, of papers have been written about laboratory hamsters. They have been used to understand circadian rhythms, chemical communication and other aspects of basic mammal biology. But their greatest research impact has been in the context of medicine. Hamsters long served as one of the most important “guinea pigs” and helped build our understanding of human ailments and their treatments. Ironically, the success of hamsters in medical research is, in no small part, due to the specifics of Aharoni’s story. Because hamsters are inbred, they suffer congenital heart disorders (dilated cardiomyopathy in particular). Heart disease is nearly as common in domestic hamsters as it is in humans. It is this particular form of dying that has made them useful animal models for our own heart disease. Perhaps more so than any other species, they die like we die and for that reason they are likely to continue to be used in labs to help us understand ourselves.

Wild Golden Hamster Research

In two expeditions carried out in September 1997 and March 1999 in northern Syria and southern Turkey, researchers found and mapped 30 burrows. None of the inhabited burrows contained more than one adult. The researchers caught six females and seven males. One female was pregnant and gave birth to six pups. All these 19 caught golden hamsters, together with three wild individuals from the University of Aleppo, were shipped to Germany to form a new breeding stock. Observations of females in this wild population revealed, contrary to laboratory populations, that activity patterns are crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk) rather than nocturnal, possibly to avoid nocturnal predators such as owls. [Source: Wikipedia]

Ben Crair wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “ Understanding the hamsters has proven more difficult. The wild populations of hamsters remain relatively unstudied. Aharoni published a paper on what he saw in 1930—the depth of the burrow, the local conditions, what the hamsters were seen eating. Observations of Syrian hamsters in the wild have been rare: one expedition in 1981, one in 1997, another in 1999, but little progress has been made. Wild Syrian hamsters have never been found outside of agricultural fields. And even in the fields, they are not common. [Source: Rob Dunn, Smithsonian magazine, March 24, 2011]

They are found only in one small part of Syria [that extends a little into Turkey] and nowhere else. Where is or was their wilderness? Maybe there is a faraway place where they run among the tall grasses like the antelope on the plains, but maybe not. Maybe the hamsters’ ancestors abandoned their pre-agricultural niche for the wheat fields around Aleppo, where wheat has been grown for as long as wheat has been grown anywhere. Or maybe the wheat itself displaced the habitat the hamsters once used.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025