Home | Category: Desert Animals

GREATER EGYPTIAN JERBOAS

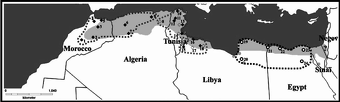

Greater Egyptian jerboa (Jaculus orientalis) are found across North Africa — in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt. They are especially common in Egypt and their range extends east through Sinai and into southern parts of Israel; formerly, the species inhabitated areas of Saudi Arabia. Greater Egyptian jerboas lives in humid coastal and salt semi-deserts and in subtropical shrubland, including rocky valleys and meadows. They are also found in barley fields of the semi-nomadic Bedouin tribes. The lifespan of Greater Egyptian jerboas in the wild is unknown; however, the offspring of a pregnant female captured for a study lived for over six years in captivity. [Source: Whitney Wiest, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Greater Egyptian jerboas are occasionally found in pet markets and they are said to have a tame disposition and manageable size. They are sometimes regarded as a crop pests. They are fond of barley and on occasion raid Bedioun agricultural fields. Greater Egyptian jerboas have been hunted by Bedouins for meat and fur, used as trim, and because they are considered pests. To capture them Bedouin pour water into their burrows, forcing the animals to run out. They also dig up burrows, and set traps by burrow openings.

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are listed as a species of Least Concern. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they have no special status. They are regarded as crop pests and their main negative impact on humans is crop damage. In 1996, Greater Egyptian jerboas was designated as 'Lower Risk/Near Threatened' on IUCN Red List. In 2004, the species was re-assessed and was given a 'Least Concern' designation, meaning they are widespread and abundant.

Greater Egyptian jerboas are commonly preyed upon by snakes, Rüppel's foxes, fennecs and owls. They are mainly active at night and stays in the safety of their burrows during the day. If they feels threatened while inside the burrow they can escape through an emergency exit tunnel. When alarmed at night, if outside the burrow, greater Egyptian jerboas head towards their burrow or another safe, sheltered area. Its normal bipedal walking/running gait turns into great leaps as it flees a predator. These leaps have been measured at 1.5 to three meters long and one meter high.

RELATED ARTICLES:

JERBOAS OF THE MIDEAST AND NORTH AFRICA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES africame.factsanddetails.com

JERBOAS OF CENTRAL ASIA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

PYGMY JERBOAS (WORLD'S SMALLEST RODENTS): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

HAMSTERS: TAXONOMY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

HAMSTER SPECIES IN EURASIA: EUROPEANS, ROBOROVSKIS, CAMPBELL'S DWARVES factsanddetails.com

GOLDEN (SYRIAN) HAMSTERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, DISCOVERY, DOMESTICATION africame.factsanddetails.com

MOUSE-LIKE HAMSTERS: CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES, BEHAVIOR, AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

GERBILS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

GERBIL SPECIES IN ASIA: MONGOLIAN, GREAT, INDIAN factsanddetails.com

GERBILS OF THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA africame.factsanddetails.com

JIRDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES AND REPRODUCTION africame.factsanddetails.com

Greater Egyptian Jerboa Characteristics and Diet

Greater Egyptian jerboas on average weigh 134 to 139.1 grams (4.72 to 4.90 ounces) and have a head and body length that ranges from 9.5 to 16 centimeters (3.74 to 6.30 inches). The tail length averages 12.8 to 25 centimeters (5 to 9.8 inches). Their body temperature is 37.0 degrees Celcius and heir average basal metabolic rate is 0.775 watts (or 3.649 kcal per kilogram per hour). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. [Source: Whitney Wiest, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Greater Egyptian jerboas are covered pale, yellowish-dark, sandy fur on their back side and have white fur on their undersides. Inner and outer ear areas are covered with thin hair. Eyelashes and sensory hairs are black, while the whiskers are a grey-white. The long tail is also covered with thin, short hair and ends in a tuft of black and white hair; When standing, Greater Egyptian jerboas rest their tail in a curved position, providing support and balance.

The body of Greater Egyptian jerboas is very compact with a large head and limbs adapted for jumping. The hindlimbs are roughly four times as long as the forelimbs and are used for leverage when the animal jumps great distances. The metatarsal bones of the hind feet are fused together into a 'cannon bone,' and the first and fifth digits are missing, leaving three long, flattened toes. Hair on the sides and bottom of toes increase the surface area of the foot and aid in locomotion

Greater Egyptian jerboas primarily eat succulent roots, sprouts, seeds, grains, a few cultivated vegetables, and occasional insects. They use their front paws to sift through sand and loose soil looking for seeds, to handle food, and to climb plants. Greater Egyptian jerboas derives water from green vegetation and can live without drinking free-standing water for long periods of time. When related desert jerboa species do drink from a body of water, they dip their front paws in the water and then lick them, instead of drinking directly from the source.

Greater Egyptian Jerboa Behavior and Communication

Greater Egyptian jerboas are saltatorial (adapted to leaping), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), hibernate (the state that some animals enter during winter in which normal physiological processes are significantly reduced, thus lowering the animal’s energy requirements) and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). It is difficult to assess their home range but during one field survey, one to over 50 individuals were counted over a distance of 0.8 kilometers. [Source: Whitney Wiest, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Greater Egyptian jerboas emerge from their burrows during late dusk and retreat at dawn. Related jerboas begin their nocturnal activities with a sand bath, removing oils and fat from their fur, and grooming themselves with their paws and teeth. When in the burrow, they sleep most of the time or rest in a crouching position. If in a group, jerboas like to sleep on top of one another, helping to retain body heat in the winter months. They are social and play with each other; Bedouins have reported that the jerboas congregate in large burrows for "play" on some nights.

Greater Egyptian jerboas sense using vision, touch, sound, vibrations and chemicals usually detected with smelling or smelling-like senses. They have keen hearing and eyesight, which helps them in their nocturnal lifestyle. Greater Egyptian jerboas communicate with touch, sound and chemicals and employ pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species) and vibrations.

Greater Egyptian jerboas are social animals. Captive jerboas make sounds to express their anger or annoyance with other jerboas. They have also been observed rhythmically tapping and scratching the floor of their cages. The action gives the impression of communication; however, the animal might only be imitating digging movements used to create burrows in the wild. Related desert jerboa seems to recognize one another by smell when in captivity. Individuals close their eyes, come together until their noses touch, and remain in contact this way for one to five seconds.

Greater Egyptian Jerboa Burrows and Hibernation

Greater Egyptian jerboas dig burrows into desert sand and clay by brushing away, pushing, or beating the soil. Burrows can range from 0.75 meters to 1.75 meters in depth and one to 2.5 meters long. All burrows have a main chamber where the jerboa lives and most have an emergency exit tunnel as well. Whitney Wiest wrote in Animal Diversity Web: The nest is frequently lined with camel hair, dry shredded vegetation, and plant wool to keep the inhabitant warm. In rainy winters burrows are made on the sides of hills to avoid flooding, and the entrance is usually left open. In the summertime, burrows are usually on less elevated areas near vegetation; the entry hole is plugged with soil, possibly to prevent snakes and warm air from entering.

Earlier studies observed neither hypothermia nor temperature-induced torpor in Jaculus, suggesting that Greater Egyptian jerboas neither hibernated nor aestivated and was active year-round. However, Greater Egyptian jerboas do not store food or have cheek pouches, and reports by Bedouins suggest that these animals disappear in the winter, implying extended below ground occupancy of burrows. This might be in response to extremely cold temperatures or food shortages.

Later investigations supported this hypothesis and have depicted Greater Egyptian jerboas as an ideal model for deep hibernation (the state that some animals enter during winter in which normal physiological processes are significantly reduced, thus lowering the animal’s energy requirements). It has been found that during cold periods Greater Egyptian jerboas accumulates lipid reserves, developing a seasonal obesity. Following this accumulation, the jerboa's body temperature decreases to around 9.8°C and the heart frequency drops to about 9.3 beats/min; an active jerboa maintains a 37°C body temperature with a heart rhythm around 300 beats/min.

Greater Egyptian Jerboa Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Greater Egyptian jerboas are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time). They engage in seasonal breeding — breeding once a year, from February to July. The average gestation period is 35 to 40 days. The number of offspring ranges from two to eight, with the average number of offspring being three. 3, with the average number of offspring being 2.5. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. During the pre-weaning stage provisioning and protecting are done by females. [Source: Whitney Wiest, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Other jerboa species display a particular courting behavior that involves the male standing upright in front of a female. He then lowers himself to the height of the prospective mate and slaps her regularly with his front limbs. Captive breeding efforts have been unsuccessful,

When young Greater Egyptian jerboas is born, their forelimbs and hindlimbs are the same length, the tail is short, fur is absent, and the eyes and ears are closed. For the first four weeks, pups move by crawling with their forelimbs, dragging their body and hindlimbs along. After four weeks, quadruped locomotion emerges, and after about 47 days old they are capable of bipedal locomotion. Lesser Egyptian jerboa young open their eyes after five weeks and eat solid food at six weeks. They are independent at 8 to 10 weeks and sexually mature at eight to 12 months.

After birth, mother Greater Egyptian jerboas stays with their young in their burrow during the breeding and nursing season until the altricial offspring are self-sufficient. She provides the young with food and resources as well as the protection and shelter of the burrow. It is presumed that the mother teaches her offspring how to hop and get around as well as survival skills until independence is reached, about the time of weaning. It is unknown if males have a role in parenting.

Lesser Egyptian Jerboas

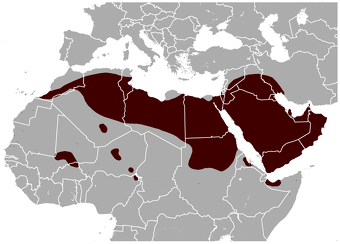

Lesser Egyptian jerboas (Jaculus jaculus) are also known as desert jerboas. They live North Africa, the Middle East, Arabia and some parts of Central Asia in countries such as Sudan, Israel, and Morocco. The species is especially common in Egypt — one reason for its common name, Lesser Egyptian jerboas lives in desert and semi-desert areas that can be sandy or stony. They can also be found in less numbers in rocky valleys and meadows.[Source: Theresa Keeley, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Lesser Egyptian jerboas have a lifespan in the wild of three to four years and have lived up to 6.4 years in captivity. Efforts have been made to bred them in captivity but these efforts have been unsucesssful due to lack of maternal care. However, captured young jerboas have been successfully tamed and kept as pets.

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, lesser Egyptian jerboas are listed as a species of Least Concern. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they have no special status. Some people eat jerboas for food. Their greatest threat is loss of habitat, still their populations seem healthy largely as a result of living in places where humans don’t go or are few in number.

Known predators of lesser Egyptian jerboas include pallid foxes, Nile foxes, striped weasels, moila snakes and saw-scaled vipers. The main defenses that lesser Egyptian jerboas have against predator is their speed and agility. They can hop very fast and make large leaps and can move in an erratic and unpredictable way. Individuals often run escape into their burrows or any nearby cover or holes they can find. They do not bite often when handled, and do not seem to have any real means of defense against predators if caught.

Lesser Egyptian Jerboa Characteristics and Diet

Lesser Egyptian jerboas range in weight from 43 to 73 grams (1.52 to 2.57 ounces), .with their average weight being 55 grams (1.94 ounces). They have a head and body length that ranges from 95 to 11 centimeters (3.74 to 4.33 inches), with the average being 10 centimeters (3.94 inches). The tail is very long — 12.8 to 25 centimeters (5 to 9.8 inches) — and is used for balance and has a clump of hairs at the tip.. Their average basal metabolic rate is 0.515 watts. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Females are larger than males. [Source: Theresa Keeley, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Lesser Egyptian jerboas are one of the smallest species of jerboa. They have a darkish back and lighter colored underbelly. There is also a light-colored stripe across its hip. Jerboas ressemble a tiny kangaroo in terms posture and movement. Their hind feet are incredibly large — 5 to 7.5 centimeters (two to three inches) and used for leaping. Each hind foot has three toes. These jerboa have moderately large eyes and ears relative to their body size.

Lesser Egyptian jerboas are primarily herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) but are also recognized as granivores (eat seeds and grain) and omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals). Among the plant foods they eat are roots, tubers grass, seeds, grains, and nuts. Animal foods include insects. Although they live in the desert, lesser Egyptian jerboas do not drink; instead they rely on green plant parts and insects to provide them with water.

Lesser Egyptian Jerboa Behavior

Lesser Egyptian jerboas are fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), saltatorial (adapted to leaping), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), hibernate (the state that some animals enter during winter in which normal physiological processes are significantly reduced, thus lowering the animal’s energy requirements) and employ aestivation (prolonged torpor or dormancy such as hibernation) and solitary. The size of their range territory is 10 to 14 square kilometers. [Source: Theresa Keeley, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Lesser Egyptian jerboas are generally solitary animals that dig burrows in hard ground and sand. The burrows are dug in a counterclockwise spiral. and reach a depth of around 1.2 meters (four feet). The the nest is at the very bottom and there a couple of additional exits off of the main burrow. Lesser Egyptian jerboas molt sometime from March to July and engage in sandbathing. For the latter, they dig a shallow depression in the sand and lay in it and rub their bodies along their sides. During hot and dry periods, lesser Egyptian jerboas aestivates in its burrow. It is still debated whether or not Lesser Egyptian jerboas hibernate in the winter; only a few individuals have been observed doing it.

Lesser Egyptian jerboas move about by hopping with their huge hind legs. They leap can leap up to three meters with a single bound. They generally move around only at night when it is cooler in the desert. Jerboas leave their burrow after sunset and can travel long distances, about 10 kilometers, away from it in search of food. They can cover a lot of ground quickly by hopping. stride.

Lesser Egyptian jerboas sense using vision, touch, sound, vibrations and chemicals usually detected with smelling or smelling-like senses. They communicate with touch and chemicals usually detected by smelling. Lesser Egyptian jerboas in captivity seem to recognize each other by smell. They close their eyes and come together until thier noses touch and keep contact for one to five seconds in this way. /=\

Lesser Egyptian jerboa skeletons showing a jump movements sequence, Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, Paris

Lesser Egyptian Jerboa Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Lesser Egyptian jerboas are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time) and engage in seasonal breeding. They breed at least twice yearly, and every three months in captivity. It appears that although male Lesser Egyptian mate with a number of females, females only mate with one male. Males attract females standing on their hind legs in front of a female. When a female approaches, the male faces her and slaps her at regular intervals with his short front limbs. [Source:Theresa Keeley, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Breeding occurs from June to July and from October to December. The gestation period is 25 days to 45 days. The number of offspring ranges from one to six, with the average number being three. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Pre-weaning and Pre-independence provisioning are provided by females. The average weaning age is six weeks and the age in which they become independent ranges from eight to ten weeks. Females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at eight to 12 months, males do so around four and half months.

Egyptian jerboa young are born naked with closed eyes and short vibrissae, and relatively short hindlimbs and tail. They weigh about two grams and their head and body is around 2.5 centimeters (one inch long) and their tail is around 1.6 centimeters in length. Their hind feet are 0.9 centimeters and are much shorter in relation to their bodies than is the case with adults Their eyes are closed over, but they can crawl around using their front limbs.They crawl with their forelimbs in the same fashion as Greater Egyptian jerboas described above.

Lesser Egyptian jerboas young open their eyes after five weeks and eat solid food at six weeks. Lesser Egyptian jerboas bred in captivity do not survive because their mother ignores them. In one case, the mother kicked the babies out of the nest. In the wild, offspring and mother are brought into close contact in the burrow and young do not leave the burrow until they are self-sufficient at around eight weeks of age.

Jerboa species: 15) Williams's Jerboa (Scarturus williamsi), 16) Syrian Five-toed Jerboa (Scarturus aulacotis), 17) Euphrates Jerboa (Scarturus euphraticus), 18) Hotson' ’ s Five-toed Jerboa (Scarturus hotsoni), 19) Small Five-toed Jerboa (Scarturus elater), 20) Vinogradov’s Jerboa (Scarturus vinogradovi), 21) Four-toed Jerboa (Scarturus tetradactylus), 22) Greater Fat-tailed Jerboa (Pygeretmus shitkovi), 23) Lesser Fat-tailed Jerboa (Pygeretmus platyurus), 24) Dwarf Fat-tailed Jerboa (Pygeretmus pumilio), 26) Northern Three-toed Jerboa (Dipus sagitta), 27) Mongolian Three-toed Jerboa (Stylodipus andrewsi), 28) Thick-tailed Three-toed Jerboa (Stylodipus telum), 29) Dzungarian Three-toed Jerboa (Stylodipus sungorus), 30) Lichtenstein’s Jerboa (Eremodipus lichtensteini), 31) Greater Egyptian Jerboa (Jaculus orientalis), 32) Blanford’s Jerboa (Jaculus blanfordi), 33) Lesser Egyptian Jerboa (Jaculus jaculus), 34) African Hammada Jerboa (Jaculus hirtipes), 35) Arabian Jerboa (Jaculus loftusi)

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025