Home | Category: Government, Military and Justice

QUEENS OF ANCIENT EGYPT

The Pharaoh had only one legal wife — the queen. She was of royal or of high noble birth, and may have been the “daughter of the god" such as of the late king, and therefore the sister of her husband. Her titles testify to her rank at court. The queen of the Old Kingdom was called “She who sees the gods Horus and Seth.. the possessor of both halves of the kingdom, the most pleasant, the highly praised, the friend of Horus, the beloved of him who wears the two diadems.” The queen during the New Kingdom was called “The Consort of the god, the mother of the god, the great consort of the King; “" and her name is enclosed like that of her husband in a cartouche. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The queen appears as a rule to have been of equal birth with her husband; she took her share in all honors. Unfortunately the monuments always treat her as an official personage, and therefore we know scarcely anything of what took place in the “rooms of the royal wife. " The artists of the heretic king Akhenaten in rare fashion emancipate themselves from conventionalities, and give us a scene out of the family life of the Pharaoh. We see him in an arbour decked with wreaths of flowers sitting in an easy chair, he has a flower in his hand, the queen stands before him pouring out wine for him, and his little daughter brings flowers and cakes to her father.

After the death of her husband the queen still played her part at court, and as royal mother had her own property, which was under special management. " Many of the queens had divine honours paid to them even long after their deaths — two especially at the beginning of the New Kingdom, Ahhotep and Ahmose Nefertari, were thus honoured; they were probably considered as the ancestresses of the 18th dynasty.

“The main sources for the study of queens and their role in divine kingship and the Egyptian state are texts and representational art, including reliefs, stelae, and statues in temples and tombs, small artifacts, administrative papyri, and diplomatic texts in cuneiform writing from Egypt and abroad. Of particular significance is the context in which the queens were depicted, as well as the shape of their tombs and the location of their tombs in relation to the kings’ mortuary complexes. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“When Women Ruled the World: Six Queens of Egypt” by Kara Cooney (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Cleopatras: Discover the Powerful Story of the Seven Queens of Ancient Egypt!” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (2024) Amazon.com;

”Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh” by Joyce A. Tyldesley (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Woman Who Would Be King” by Kara Cooney (2014) Amazon.com;

“Hatchepsut: The Life of the Female Pharaoh (1507 - 1458 BCE 18th Dynasty)”

by Ron Schaefer Amazon.com;

“The Royal Women of Amarna: Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt" (1996) Amazon.com;

“Women, Gender and Identity in Third Intermediate Period Egypt: The Theban Case Study” by Jean Li (2017) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Egypt” by Gay Robins (1993) Amazon.com;

“Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt” by Carolyn Graves-Brown (2010) Amazon.com;

“Daughters of Isis: Women of Ancient Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesley (1994) Amazon.com;

Women in Ancient Egypt: Revisiting Power, Agency, and Autonomy

by Mariam F. Ayad (2022) Amazon.com;

Queens Who Ruled Egypt

During ancient Egypt’s roughly 3,000-year history, only six women — Merneith, Sobekeferu (Neferusobek), Hatshepsut, Nefertiti, Tawosret, and Cleopatra — ruled. Yet queens presided over some of the most stable, prosperous periods. According to the Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments: Most served, at least nominally, as regents or co-regents for their children. All were assisted by a political culture that valued membership in the royal family more than gender and by a socioeconomic system that allowed women to own property and conduct business in their own right. [Source: Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments, Thomson Gale, 2008]

Dr Joann Fletcher of the University of York wrote for BBC: “During Egypt's 'Golden Age', (the New Kingdom, c.1550-1069 B.C.), a whole series of such women are attested, beginning with Ahhotep whose bravery was rewarded with full military honours. Later, the incomparable Queen Tiy rose from her provincial beginnings as a commoner to become 'great royal wife' of Amenhotep III (1390-1352 B.C.), even conducting her own diplomatic correspondence with neighbouring states. |::| [Source: Dr Joann Fletcher, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“The status and privileges enjoyed by the wealthy were a direct result of their relationship with the king, and their own abilities helping to administer the country. Although the vast majority of such officials were men, women did sometimes hold high office. As 'Controller of the Affairs of the Kiltwearers', Queen Hetepheres II ran the civil service and, as well as overseers, governors and judges, two women even achieved the rank of vizier (prime minister). This was the highest administrative title below that of pharaoh, which they also managed on no fewer than six occasions.

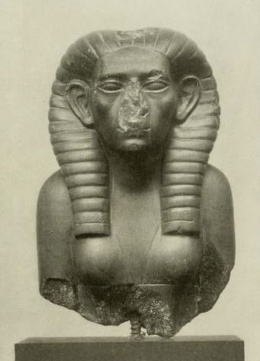

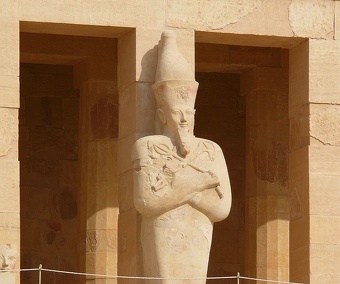

“Egypt's first female king was the shadowy Neithikret (c.2148-44 B.C.), remembered in later times as 'the bravest and most beautiful woman of her time'. The next woman to rule as king was Sobeknefru (c.1787-1783 B.C.) who was portrayed wearing the royal headcloth and kilt over her otherwise female dress. A similar pattern emerged some three centuries later when one of Egypt's most famous pharaohs, Hatshepsut, again assumes traditional kingly regalia. During her fifteen year reign (c.1473-1458 B.C.) she mounted at least one military campaign and initiated a number of impressive building projects, including her superb funerary temple at Deir el-Bahari. |::|

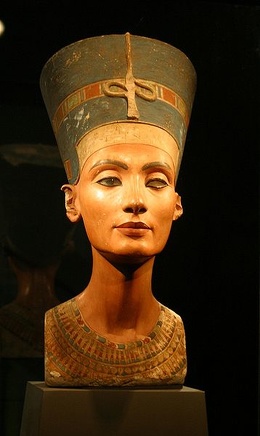

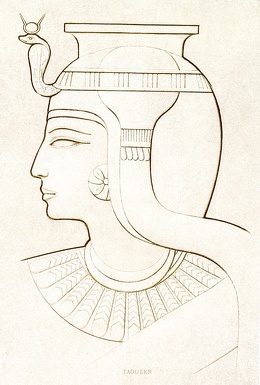

“But whilst Hatshepsut's credentials as the daughter of a king are well attested, the origins of the fourth female pharaoh remain highly controversial. Yet there is far more to the famous Nefertiti than her dewy-eyed portrait bust. Actively involved in her husband Akhenaten's restructuring policies, she is shown wearing kingly regalia, executing foreign prisoners and, as some Egyptologists believe, ruling independently as king following the death of her husband c.1336 B.C. Following the death of her husband Seti II in 1194 B.C., Tawosret took the throne for herself and, over a thousand years later, the last of Egypt's female pharaohs, the great Cleopatra VII, restored Egypt's fortunes until her eventual suicide in 30 B.C. marks the notional end of ancient Egypt. |::|

Roles of the Queens of Egypt

Kara Clooney, author a book about ancient Egyptian queens, told National Geographic History: These women were serving a patriarchy, in a context of social inequality. They were stepping in to support their husbands, brothers, or sons. The reason Egypt had women rulers again and again is because Egypt was very risk-averse and wanted a divine kingship to survive no matter what. The Egyptians knew that women ruled differently, that they weren’t warlords or rapists, they weren’t going to throttle you in the night. Not that they’re not capable of murder. But fewer women commit violent crimes today and we should assume that it was the same in the ancient world. [Source Simon Worrall, National Geographic History, December 15, 2018]

The women were placeholders for a much larger scheme of power that is dependent on masculinity. They were there to make sure the next male in line could step into the power circle. Simple biology helps us understand that it’s harder for a woman to be at the center of the circle. She can only have one, maybe two children a year. Whereas, a man can produce hundreds of children, without all the hormonal changes and the vulnerability it produces. So, she is there at a moment of crisis to protect the patriarchy when something goes wrong with the succession from man to man. As soon as it can go back to the patriarchal system, she is removed. Five of the six women in this book were called King. But that doesn’t mean that they won’t be erased a few generations later when it’s expedient for the men to remove them from the story, and claim that success outright for themselves.

Silke Roth of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Germany wrote: ““The various roles of the queen were defined in accordance with this preeminent position of the king. Against the background of fundamental changes in the ideology of kingship, in the 18th Dynasty the cultic and political significance of the queen gradually increased and was assimilated to the male ruler. At the height of this development, the “great king’s wife” Nefertiti was characterized as an almost coequal partner of the king. However, after the Amarna Period the queen once again became less important. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“According to sources from later periods of Egyptian history, after the New Kingdom the traditional concept of queenship was perpetuated, essentially unchanged. Though the royal wives of the foreign rulers from Kush wore their indigenous garments, as Egyptian queens they took on the customary titles and insignia of their Pharaonic precursors. In Egypt—unlike in their home country—they were only occasionally depicted attending the king. he royal women of the Ptolemies also adopted the traditional accoutrements of the Egyptian queen, as recent studies of their statuary and their role in temple ritual suggest. In addition to Hathor, the goddess Isis functioned as the most important divine counterpart of the queens during this period. As in Pharaonic times, some outstanding personalities appeared who functioned in an almost-equal partnership with their respective kings (above all Berenike II and III, and Cleopatra III and VII), particularly by adding kings’ titles to their queenly titulary—frequently 1rt (“female Horus”)—and by acting as sole ritualists vis-à- vis the gods. However, their role strongly resembles that of Akhenaten’s great royal wife Nefertiti as well as of other ancient Egyptian queens who acted as representatives on behalf of minor kings (though it is not at all comparable to the role of the female kings Neferusobek, Hatshepsut, and Tauseret).”

Queen’s Role in Legitimizing the King’s Right to the Throne

Silke Roth of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Germany wrote: “Although, according to divine paradigms, a king was succeeded by his son, there are numerous counter-examples of this ideal. Among the principles of legitimacy upon which a king’s right to the throne was based, the hereditary right through blood relation to a royal predecessor was of only secondary importance. Once the new sovereign succeeded to the crown (for example, through designation by a predecessor or by actual control of power), he was legitimized by the very act of holding the kingly office as “Horus” and “Son of Ra,” and therefore as legal heir to the throne—that is, through “divine legitimation.” Moreover, the king was ex officio considered as the son of his immediate predecessor, being in fact the last in line of the royal ancestors. Accordingly, the queen’s role in legitimizing the rule of her husband or son refers less to her own parentage or marriage-tie than to her ideological role as earthly embodiment of her divine counterparts. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Similarly, the king’s office was not regularly transmitted through marriage to a princess of royal blood (a “royal heiress”), nor was it the custom of the heir to the throne to marry his (half-) sister in order to confirm his rule, although a brother-sister marriage between royal siblings was possible in principle. Hence, it is not surprising that even some eminent queens were beyond doubt of non-royal origin.

“From her biological capacity of assuring the succession to the throne derived the most important ideological role of the queen—that of mother-consort of the king. As such, she guaranteed both the continual renewal of kingship and of the individual officeholder respectively. This double role was based upon the paradigm of divine mother-consorts and became manifest in the queen’s titulary and insignia, as well as in her ritual function. In fact, it was shared by the king’s wife and the king’s mother.

“As earthly embodiment of Hathor, consort of the sun god and mother of Horus, it was primarily the royal spouse who functioned as a regenerative medium for the king in his role as representative of the sun-god on earth. In conjunction with her he procreated a rejuvenated form of himself, being father and son united in one person—that is, kA-mwt.f (“bull of his mother”). In the New Kingdom this role was particularly reflected in the ritual function of the future king’s mother as “God’s wife of Amun”.

“The king’s mother gained particular importance through her son’s accession to the throne, and therefore many royal mothers did not become manifest in the sources before this event occurred (for example, Mutemwia, mother of Amenhotep III; and Tuya, mother of Ramesses II). Her specific role in legitimizing her son’s rule naturally referred to the divine parentage of the king and was reflected in her attributes, especially the vulture’s headdress and the titles zAt nTr (“daughter of the god”) and mwt nTr (“mother of the god”), both titles attested as early as the Old Kingdom. Moreover, in the so-called“legend of the divine birth of the king,” she was represented as being impregnated by the sun-god incarnate and giving birth to his heir—i.e., her son, the reigning king.”

Titles of the Queen of Egypt

Silke Roth of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Germany wrote: “The queens of ancient Egypt (i.e., the kings’ wives and kings’ mothers) were distinguished by a set of specific titles and insignia that characterized them as the earthly embodiment of the divine feminine principle. From the earliest times, queens were characterized by a specific queenly titulary and iconography, and from as early as the Middle Kingdom their name could be written in a cartouche. To be distinguished from queens are the few female rulers who took the fivefold titulary of the king and bore kingly insignia. By ensuring the continued renewal of kingship, they played an important role in the ideology of kingship. As the highest-ranking female members of the royal household, queens occupied a central position at court, as well. However, only in individual cases did they hold substantial political power. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Significantly, a feminine equivalent of the ruler’s designation as nswt (“king”) did not exist in ancient Egypt. In fact, most of the queens’ titles and epithets related them to the king and the king as the earthly embodiment of the gods, respectively. Only from the Middle Kingdom onward did their titles indicate a ruling function.

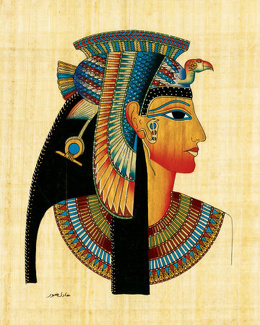

Queen Nefertari

“The most important and therefore most frequent queens’ titles include those that refer to their marriage, or kinship, to the king—Hmt nswt (“wife of the king”) and mwt nswt (“mother of the king”)—as well as the non- specific titles sAt nswt (“daughter of the king”) and snt nswt (“sister of the king”). The queenly office is also reflected in the titles mAAt 1rw-4tS (“the one who beholds Horus-Seth,” i.e., the king, used mainly in the Old Kingdom), jrjt pat (“the one who belongs to the pat,” i.e., the elite), wrt Hts (“great one of the hetes-scepter”), wrt Hst (“great one of favor”), wrt jmAt (“great one of grace,” used in the Middle Kingdom and later), and Xnmt nfr HDt (“the one who is united with the White Crown,” used in the Middle Kingdom and later, the “White Crown” being an attribute of the king). Commonly attested from the Middle Kingdom onward are Hnwt tAwi (“lady of the Two Lands,” i.e., Egypt) and, as early as the New Kingdom, Hnwt 5maw MHw (“lady of the South and the North”), Hnwt tAw nbw (“lady of all lands”), and nbt tAwy (“mistress of the Two Lands”). Evidence that the queen played a priestly role in the cult of Hathor and various other deities is provided by titles of the type Hmt nTr NN (“priestess of the god/goddess NN,” used in the Old and Middle Kingdoms) and Hmt nTr Jmn (“God’s wife of Amun,” used in the New Kingdom and later).

“In the course of a queen’s career—as her role progressed, for example, from that of a king’s daughter, to a king’s wife, to, finally, a king’s mother—the corresponding titles were added to her titulary. From as early as the Old Kingdom a typical string of “core” titles can be discerned, varying in range and order in later times. In instances where minimal titulary was provided, it appears that, at the very least, the titles “wife of the king” or “mother of the king” were mentioned.

“To obtain an heir and guarantee the succession to the throne, Egyptian kings were polygynous; therefore, usually several coexisting wives are attested for each sovereign. As a rule, only one “wife of the king” was depicted together with her husband, so it seems that only one of them officiated as queen by holding the queen’s titulary and insignia. It was not until the 13th Dynasty that the title Hmt nswt wrt (“great wife of the king”) was introduced to distinguish this “principal wife” from the secondary wives of the ruler.”

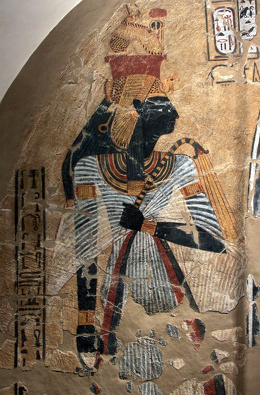

Ancient Egyptian Queen’s Ritual Duties and Court-Political Position

Silke Roth of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Germany wrote: “From the Old Kingdom onward certain titles reveal that queens played a role in the cult of deities (for example, “priestess of Hathor,” “chantress of Amun,” “sistrum-player of Mut”). However, queens were only rarely depicted as sole ritualists vis-à-vis the divine addressee (the exceptions being deceased queens, Nefertiti during the Amarna Period, and Hatshepsut and Tauseret shortly before they became female rulers). If pictured in ritual scenes, which is the case only in a comparably small number of temple reliefs, the queen habitually follows the king, supporting his ritual performance by playing the sistrum and singing in order to pacify the divinity. From the Old Kingdom onward, the queen was represented in basically this manner, assisting the king at the offering ritual, the building ritual , and the hunting ritual. From the New Kingdom onward, she was also represented in the ritual of “smiting the enemies,” exceptions being Tiy and Nefertiti, who, themselves, were depicted smiting female enemies. In the course of the New Kingdom festivals, the queen occasionally played a more active role. During the Festival of Opet, for instance, her ship towed the bark of the goddess Mut (parallel to the king’s ship towing the bark of Amun), and in the Festival of Min, she played the ceremonial role of Shemait, who encircled the king seven times reciting ritual texts. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Tawosret (died 1189 BC), also spelled Tausret or Twosret , the last known ruler and the final pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt

“The queens were the highest-ranking female members of the royal court (Snwt) and the royal household (jpt nswt)—the so-called “harem”—which also included the secondary wives of the ruler together with the royal children, and which was a powerful force in its own right. As members of the harem, queens were occasionally involved in conspiracies to carry out the murder of the king.

“Archaeological finds in New Kingdom royal residences, and tomb representations from the same period, attest to the existence of separate palace apartments or buildings for the female members of the royal household, such as we see at Memphis/Kom Medinet el- Ghurab, Thebes/Malqata, and Amarna. In all probability, at least the principal wife lived near the king and accompanied him on his journeys through the country. As the most important members of the king’s court and household—both in life and in the afterlife—queens were usually buried close to the king’s tomb, often in the immediate vicinity of his mortuary complex, and sometimes actually inside his tomb. This proximity is also illustrated in the royal necropolis of Western Thebes, where we find in the desert valleys not only the kings’ tombs but the queens’, nearby, with the related cult complexes on the edge of the cultivation.

“Due to the fact that the majority of sources refer to the queens’ role in the ideology of kingship, there is little evidence that queens held political influence. Only rarely were queens depicted or mentioned as being present at acts of state, such as royal audiences, councils, and the public rewarding of officials. A representation of a queen rewarding a noblewoman (a clear parallel to the king rewarding an official) is unique. The Amarna Period represented an exception to this norm: during that time, the public appearance of the royal couple was celebrated to propagandize a new concept of kingship that promoted the queen as an almost coequal partner of the king. In other cases in which individual queens appeared as outstanding personalities, they mostly acted as representatives on behalf of minor kings (for example, Ankhenespepy II/Pepy II, Hatshepsut/Thutmose III, Tauseret/Siptah), or in support of an absent ruler (Ahhotep/Ahmose). However, such political roles were not formally reflected in the queens’ titulary and insignia.

“Significantly, that the queen played a role in foreign policy is attested by cross-cultural, rather than Egyptian, sources, exhibiting the realpolitik (political pragmatism) of the Egyptian state. In the diplomatic correspondence between Egypt and its Near Eastern neighbors during the New Kingdom, recorded on cuneiform tablets from Amarna and the Hittite capital, Hattusas, queens featured (if only exceptionally) among the actual correspondents (e.g., the dowager queens Ankhesenamun and Tiy; and with regard to the Egyptian-Hittite treaty, Tuya and Nefertari). Numerous letters concern marriage alliances negotiated by the Egyptian ruler and the other “great kings” of Mitanni, Babylonia, Assyria, and Hatti, as well as minor vassals from Syria and Palestine, who sent their daughters to the Egyptian court. Being a pledge of good diplomatic relations, these foreign royal wives together with their courts served as permanent missions for their home countries.

“In contrast, it was very unusual for Egyptian princesses to be sent abroad to marry foreign rulers. The alleged matrimonies of Egyptian princesses with the Israelite king Solomon (during the 21st-Dynasty reign of Siamun) and the Persian king Cambyses (during the 26th- Dynasty reign of Amasis) are controversial.”

Insignia of the Ancient Egyptian Queen

Silke Roth of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Germany wrote: “From as early as the 4th Dynasty the queen was characterized by a set of specific insignia—in particular, by various headdresses and hand-held emblems. By borrowing these insignia from, or sharing them with, female deities, the queen associated herself with her divine counterparts. Typically, these goddesses functioned as mothers and consorts in divine families and therefore played an important role in the ideology of kingship. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Among the most important insignia are the vulture headdress (a cap made from a vulture’s skin) and the uraeus. Taken over by the queen from the tutelary goddesses and divine mothers Nekhbet and Wadjet, they were at first exclusively worn by the royal mothers (Dynasties 4 and 5). Later on, the vulture headdress became a symbol of motherhood par excellence and was adopted by other prototypical mother goddesses, such as Mut and Isis. From Dynasty 6 onward the king’s wives—being prospective royal mothers— also began to wear the vulture headdress and the uraeus. From the Middle Kingdom through the early 18th Dynasty the uraeus became a common emblem of the king’s daughters, as well. This association with the uraeus suggests a development in the status of the royal daughter during this period.

“In the 18th Dynasty, the double uraeus occurred as a brow ornament of royal wives and mothers. Apparently it indicated an association of the queen with the dualistic concept of Nekhbet and Wadjet, the goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt, respectively, especially when adorned with the crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt. Furthermore, it associated the queen with the two “solar eyes” and daughters of the sun god—primarily, Hathor and Tefnut. Crowned with the cow’s horns and sun disc, the so- called Hathoric uraeus appeared as single and double emblems, in clear reference to Hathor and the solar eye(s). It is first attested in the Amarna Period and was still in use in Ramesside times. Moreover, as early as Dynasty 18 a triple brow-ornament is known, consisting of two uraei flanking a vulture’s head (e.g., the uraei adorned with the crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt and the vulture's head with the double crown as the embodiment of Mut; see Bryan 2008). Triple uraei occurred on queens’ statues in the 25th Dynasty, at the earliest, and are well known from the Ptolemaic Period (304–30 B.C.), when the middle uraeus was seemingly associated with the mother goddess Isis.

“In the 13th Dynasty a crown consisting of two tall feathers attached to the so-called modius (or kalathos) was added to the queenly insignia. Frequently combined with cows’ horns and the solar disk, it became one of the most important attributes of the Egyptian queen from the New Kingdom onward. It bore a solar connotation and identified the queen as an earthly embodiment of the cow goddess Hathor in her role as consort of the sun god Ra and mistress of heaven.

“Restricted to Tiy and Nefertiti, the “great wives of the kings” Amenhotep III and Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten), were the so- called platform crown (also “tall blue crown”) and the khat-headdress, the latter associating the queen with the tutelary goddesses Isis, Nephthis, Selqet, and Neith (see the "first version" of the famous wooden head of Queen Tiy from Kom Medinet Ghurab).

“The divine was-scepter and the papyrus scepter of the goddess Wadjet were occasionally attested as queenly insignia in the Old Kingdom, when they frequently appeared in combination with the ankh-sign. These representations generally occur in the queens’ tombs, so it seems that they represented deceased, “deified” royal wives. A certain degree of deification of the living queen, in parallel to the king, was indicated by New Kingdom depictions of queens wearing the ankh-sign and carrying divine scepters. First attested in the Second Intermediate Period, one of the most frequent hand-held emblems of the New Kingdom queen was the so-called fly-whisk.”

Queen Hetepheres’s Tomb

Hetepheres I was a queen of Egypt during the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt (around 2600 B.C.) who was a wife of one king, the mother of the next king, the grandmother of two more kings, and the figure who tied together two dynasties. Hetepetheres was the mother of Khufu, the second king of the 4th dynasty and builder of the Great Pyramid. She may have been a wife of King Sneferu, the building of the first true pyramid, was the grandmother of two kings, Djedefre and Khafre. The latter was the builder of the second great pyramid at Giza. [Source Wikipedia]

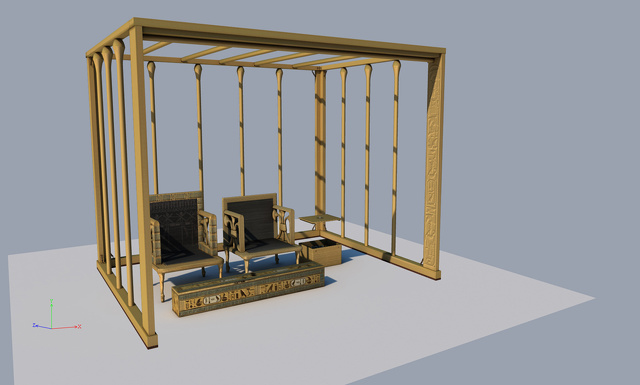

The burial goods found in Hetepheres tomb are perhaps only second to those found in the Tomb of King Tutankhamun (King Tut). Hetepheres tomb’s was discovered near the Great Pyramid of Giza by American archaeologist and Harvard Egyptologist George Reisner not that long after Tutankhamun’s was. When the tomb of Hetepheres was opened in January 1926, archaeologists were awed by the golden funerary furniture they saw. Gilded chairs, a bed, and a canopy that could be disassembled had been severely damaged by water filtering into the tomb, but they were not beyond repair. Meticulous restoration allowed many of the pieces to be returned to their royal splendor. [Source Irene Cordon, National Geographic History, March 31, 2022]

Reisner described the burial chamber and its contents as follows: “Partly on the sarcophagus and partly fallen behind it lay about twenty gold-cased poles and beams of a large canopy. On the western edge of the sarcophagus were spread several sheets of gold inlaid with faience, and on the floor there was a confused mass of gold-cased furniture.” In addition to a canopy and bed, an armchair and an elaborate carrying chair were recovered. The tomb’s owner — Hetepetheres — was inscribed on the carrying chair. The carrying chair is made of gilded wood with inlaid faience, includes decorations of falcons perched on papyrus columns.

According to National Geographic: Following the excavation, the armchair was restored and is now displayed at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. After Reisner’s death in 1942, renewed interest in the retrieved fragments from Tomb G7000X spurred the mammoth task of reconstructing the elaborate carrying chair, in all its golden splendor. It is housed today at the Harvard Museum of the Ancient Near East in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The canopy consists of 25 different pieces and was found disassembled. The supports feature carved reliefs of the falcon-headed god Horus. One of several gold chests, this box may have contained the curtains that would once have covered the canopy. This armchair is gilded with gold leaf. Papyrus flower motifs form the armrests, with feet in the form of lion claws. The queen’s gilded bed is masterfully carved. Each bedpost is shaped like a lion’s leg complete with paws and claws. A silver and gold headrest, commonly found in Old Kingdom burials, was inside a gold chest.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “This Egyptian queen's tomb lay untouched for more than 4,000 years” by Irene Cordon nationalgeographic.com

Queen Ankhnespepi II

Queen Ankhnespepi II was among the most powerful female leaders of Egypt’s Old Kingdom (2649–2130 B.C.). She was married to two kings of the Sixth Dynasty — Pepi I and Merenre — and served as regent when her son Pepi II became king at the age of six. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2018]

Archaeology magazine reported: discoveries by the Swiss-French archaeological mission at the Saqqara necropolis are providing further evidence of her importance. The team has found what appear to be the top portions of the two obelisks that would have stood at the entrance to the queen’s funerary temple. Both measure 3.5 feet on a side, and the larger is around eight feet tall, making it the largest Old Kingdom obelisk fragment yet discovered and indicating that the full obelisk would have stood more than 16 feet tall. Notably, the obelisks were made of granite, which was usually reserved for kings.

“The team, led by Philippe Collombert of the University of Geneva, also found a wooden statue head whose stylistic features — thin cheeks, large circular earrings — suggest it dates to the New Kingdom, though there are no wealthy graves from that period in the area. There is a very slight chance the head could represent Queen Ankhnespepi II, says Collombert. Radiocarbon dating will, he hopes, help find the answer.

Neferusobek — Egypt's First Female Pharaoh?

Neferusobek (Sobekneferu) was the first woman to take the Egyptian kingship as her formal title. The product of the royal harem and nursery during the 12th dynasty (1939–1760 B.C.), she was the daughter of one of hundreds of women who sexually served King Amenemhat III. Kara Cooney wrote in National Geographic: The royal princess understood that in order to maintain the familial lineage she would one day marry her aged father, or, when he died, she would be linked to her brother, the next king, as a great royal wife of the highest bloodline. (In fact, Neferusobek’s mother may have been the king’s daughter, too, though there is no record of it.) Even though it started out that way, this was not to be her fate. [Source: Kara Cooney, adapted from “When Women Ruled the World”, National Geographc Partners, October 30, 2018]

Upon his death, King Amenemhat III son, Amenemhat IV, assumed the throne and as planned, Neferusobek became his wife. For Egyptian nobility, this news was greeted with a great sigh of relief, knowing that their status quo would be upheld, for another few decades at least, and that new heirs would soon enter the royal line. Neferusobek was now queen, and a king’s daughter to boot. After just nine years of rule, however, Amenemhat IV died, having produced no viable heirs.

All the courtiers looked to the royal family to solve the situation: to maintain the balance of power among the elites, to keep the wealth pouring in. The 12th dynasty found itself in a succession crisis of the highest order. As the highest-ranked family member left, Neferusobek stepped forward as nothing less than king, using her descent from the great King Amenemhat III to justify her rule. For the first time in human history, a royal Egyptian woman claimed the highest office in the land — the kingship itself — for the simple reason that there was no royal man to take it.

See Separate Article: RULERS OF THE MIDDLE KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Queen Hatshepsut

Queen Hatshepsut was the only female to rule Egypt as a full pharaoh in a period when Egypt was strong. Often depicted as a man with a false beard, she rose to power after claiming divine birth. Her name means “the first, repeatable lady.” Other women ruled but they did so in weak period. Twosret was another female ruler. She ruled from 1198 B.C. to 1190 B.C. One, possibly two, other female pharaohs ruled briefly. Cleopatra came along 14 centuries after Hatshepsut. She wasn’t a Pharaoh or even full-blooded Egyptian but rather a Greek that ruled over the remains of a kingdom established by Alexander the Great. [Source: Chip Brown, National Geographic. April 2009; Elizabeth Wilson, Smithsonian magazine, September 2006; Peter Schjeldahl, The New Yorker]

Hatshepsut was the Queen of Egypt during the 18th Dynasty. The daughter of Thutmose I, she married Thutmose II. When he ascended to the throne she became the real ruler. When he died she acted as regent for his son, Thutmose III, then had herself crowned as Pharaoh. Maintaining the fiction that she was a male, she was represented with the regular pharaonic attributes, including a beard. Hatshepsut built a magnificent funerary temple at Deir el-Bahri on the west bank of the Nile at Thebes and sent a large commercial expedition to the land of Punt, in modern Ethiopia. [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003; [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Queen Hatshepsut ruled from 1479 to 1458 B.C. She was referred to by both male and female pronouns depending on the situation but was regarded politically as an “honorary man.” There was no Egyptian word for "Her Majesty." People addressed her as "His Majesty." Bas-reliefs and statues often depict her with a lion’s mane and a male headdress in addition to the false beard.

See Separate Article: HATSHEPSUT (1479 TO 1458 B.C.): HER FAMILY, LIFE AND REIGN africame.factsanddetails.com ; HATSHEPSUT REIGN (1479 TO 1458 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

Nefertiti

Nefertiti is one the best known queens of Egypt. She is depicted in more sculpture and artwork than her famous husband, the sun-disk worshipping Pharaoh Akhenaten, who tried to introduce monotheism to ancient Egypt. Queen Nefertiti was the stepmother to King Tutankhamun and may have ruled as a pharaoh in her own right. She lived in the 14th century B.C. during the 18th dynasty, but the years of Nefertiti's birth and death are not known with any certainty. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, February 1, 2023]

Dr Kate Spence of Cambridge University wrote for the BBC: “Akhenaten's 'great king's wife' was Nefertiti and they had six daughters. There were also other wives, including the enigmatic Kiya who may have been the mother of Tutankhamun. Royal women play an unusually prominent role in the art of the period and this is particularly true of Nefertiti who is frequently depicted alongside her husband. Nefertiti disappears from the archaeological record around year 12 and some have argued that she reappears as the enigmatic co-regent Smenkhkare towards the end of Akhenaten's reign. [Source: Dr Kate Spence, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Akhenaten was originally named Amenhotep IV. He launched a revolution that saw Egypt's religion become focused around the worship of the Aten, the sun disk. He built a new capital city called Akhetaten (modern-day Amarna) that had temples dedicated to the Aten. According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Some scholars have contemplated Nefertiti’s role in the religious reform of Egypt, contemplating if it was Nefertiti who urged her husband toward the religious reform or if he did so under his own volition. Little has been written about Nefertiti’s role with the king, however, from scribe texts, it is certain that she bore Akhenaten 6 daughters and no sons, and shared a near co-rulership with the king. Unfortunately, the lack of male sons left Akhenaten with no male royal heir to the throne. As a result, Akhenaten appointed an heir outside of the bloodline. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

See Separate Article: NEFERTITI: HER LIFE, BEAUTY, BUST AND MARRIAGE TO AKHENATEN africame.factsanddetails.com

Cleopatra

Cleopatra (Cleopatra VII, 69-30 B.C.) is one of the most famous women of all a time. A Greek Queen of Egypt, she played a major role in the extension of the Roman Empire and was a lover of Julius Caesar, the wife of Marc Antony and a victim of Augustus Caesar, the creator of the Roman Empire. Coin portraits and a bust reportedly made in her lifetime show her with a prominent nose and a large forehead. There were reports she had rotten teeth. But despite these flaws she is one of the world’s most famous seductresses.

Cleopatra reigned from roughly 51-30 B.C. and was the last ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty, which ruled Egypt for nearly 300 years. "Fierce, voluptuous, passionate, tender, wicked, terrible, and full of poisonous and rapturous enchantment" is what Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote about Cleopatra in 1858. Shakespeare made her into a romantic heroine described her as a magnificent creature with a burning soul and deep love for Antony”...”Other women cloy / The appetites they feed, but she makes hungry / Where most she satisfies,” Shakespeare wrote....”George Bernard Shaw saw her as purring sex kitten. Closer to her own time, Propetius called her a "harlot queen of incest." Historians often mark her death as the end of both ancient Egypt and ancient Greece and the beginning of the Roman Empire.

The critic Harold Bloom called Cleopatra the “world’s first celebrity.” Based on the number of books written about her (329 in 1999 in the Library of Congress collection), Cleopatra is the world's seventh most famous woman. Cleopatra was immortalized in plays by George Bernard Shaw and Shakespeare and played by Vivien Leigh and Elizabeth Taylor in Hollywood films.

RELATED ARTICLES:

CLEOPATRA (69-30 B.C.): LOOKS, SEX LIFE, FAMILY AND DEATH africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CLEOPATRA'S RULE (51-30 B.C.): POLITICS, LEADERSHIP AND TIES WITH THE ROMANS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CLEOPATRA LEGACY: POPULARITY, CELEBRITY, ALLURE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CLEOPATRA, CAESAR, MARC ANTONY AND THE PARTHIANS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OCTAVIAN, THE BATTLE OF ACTIUM AND THE DEMISE OF ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Amarna Palace, the Amarna Project

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024