Home | Category: Late Dynasties, Persians, Nubians, Ptolemies, Cleopatra, Greeks and Romans

CLEOPATRA (69-30 B.C.)

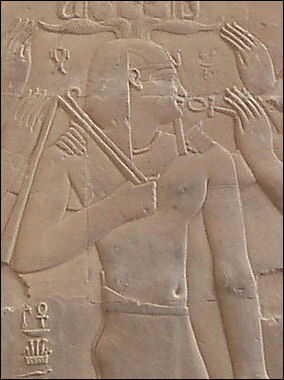

Cleopatra from the Ruins of Dendera

Cleopatra (Cleopatra VII, 69-30 B.C.) is one of the most famous women of all a time. A Greek Queen of Egypt, she played a major role in the extension of the Roman Empire and was a lover of Julius Caesar, the wife of Marc Antony and a victim of Augustus Caesar, the creator of the Roman Empire. Coin portraits and a bust reportedly made in her lifetime show her with a prominent nose and a large forehead. There were reports she had rotten teeth. But despite these flaws she is one of the world’s most famous seductresses. [Source: Chip Brown, National Geographic, July 2011; Stacy Schiff, Smithsonian magazine, December 2010; Judith Thurman, The New Yorker, May 7, 2001 and November 15, 2010; Barbara Holland, Smithsonian, February 1997]

Cleopatra reigned from roughly 51-30 B.C. and was the last ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty, which ruled Egypt for nearly 300 years. "Fierce, voluptuous, passionate, tender, wicked, terrible, and full of poisonous and rapturous enchantment" is what Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote about Cleopatra in 1858. Shakespeare made her into a romantic heroine described her as a magnificent creature with a burning soul and deep love for Antony”...”Other women cloy / The appetites they feed, but she makes hungry / Where most she satisfies,” Shakespeare wrote....”George Bernard Shaw saw her as purring sex kitten. Closer to her own time, Propetius called her a "harlot queen of incest." Historians often mark her death as the end of both ancient Egypt and ancient Greece and the beginning of the Roman Empire.

The critic Harold Bloom called Cleopatra the “world’s first celebrity.” Based on the number of books written about her (329 in 1999 in the Library of Congress collection), Cleopatra is the world's seventh most famous woman. Cleopatra was immortalized in plays by George Bernard Shaw and Shakespeare and played by Vivien Leigh and Elizabeth Taylor in Hollywood films.

Cleopatra as we said above was officially Cleopatra VII. “Cleopatra” means “fame of the father” and was a popular name among the Macedonian elite before the Ptolemies even came to power. Alexander the Great’s sister, step-mother and other fairly close female relatives were named Cleopatra. Many royal women during the Ptolemic period were named Cleopatra.

RELATED ARTICLES:

CLEOPATRA'S RULE (51-30 B.C.): POLITICS, LEADERSHIP AND CAESAR africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CLEOPATRA'S LEGACY: CELEBRITY, ALLURE, SKIN COLOR africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SEARCH FOR CLEOPATRA'S TOMB africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MARC ANTONY: HIS LIFE, RELATIONS WITH CAESAR AND MILITARY CAMPAIGNS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OCTAVIAN AND MARK ANTONY AFTER CAESAR’S DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CLEOPATRA AND MARC ANTONY: ROMANCE, EVENTS, EXTRAVAGANCE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BATTLE OF ACTIUM europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OCTAVIAN AND DEATHS OF ANTONY, CLEOPATRA AND THEIR CHILDREN europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece and Rome: House of Ptolemy houseofptolemy.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; llustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Department of Classics, Hampden–Sydney College, Virginia hsc.edu/drjclassics Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Cleopatra: A Life” by Stacy Schiff (2010) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra” by Diane Stanley (1998) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra: the Last Queen of Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesly (2008) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra” by Michael Grant (2000, 1972) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra: Histories, Dreams and Distortions” by Lucy Hughes-Hallet (1990) Amazon.com;

“Women & Society in Greek & Roman Egypt” by Jane Rowlandson (1998) Amazon.com;

“Antony and Cleopatra” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Cleopatras: Discover the Powerful Story of the Seven Queens of Ancient Egypt!” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Memoirs of Cleopatra” by Margaret George (1997), Novel and Source of TV miniseries Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra's Daughter: A Novel” by Michelle Moran (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Last Dynasty: Ancient Egypt from Alexander the Great to Cleopatra” by Toby Wilkinson (2024) Amazon.com;

“Ptolemy I: King and Pharaoh of Egypt,” Illustrated, by Ian Worthington (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Last Pharaohs: Egypt Under the Ptolemies, 305–30 BC” by J. G. Manning (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Fall of Egypt and the Rise of Rome: A History of the Ptolemies” by Guy de la Bedoyere (2024) Amazon.com;

“Alexandria: The City that Changed the World” by Islam Issa (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

Books and Sources on Cleopatra

Cleopatra on a coin Books: “Cleopatra: the Last Queen of Egypt” (Basic Books 2008) by Joyce Tyldesly, a lecturer in Egyptology at the University of Manchester in England; “ Cleopatra: Beyond the Myth” By M Chauveau, translated by D. Lorton; “ Memoirs of Cleopatra” by Margaret George Pan, a 1,000-page historical novel with vivid historical details; “Cleopatra” by Michael Grant (Phoenix Press (paperback), 2000 (originally published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson, Great Britain, 1972); “Cleopatra: Histories, Dreams and Distortions” by Lucy Hughes-Hallet (Harper & Row, 1990); “Women & Society in Greek & Roman Egypt” by Jane Rowlandson (Cambridge University Press, 1998); “Antony and Cleopatra” by Adrian Goldsworthy ((Yale, 2010); “Cleopatra” by Duane Roller (Oxford, 2010); “Cleopatra: A Life” by Stacy Schiff; (Little Brown, 2010).

Very little hard evidence about Cleopatra exists. Most of what know about her today is based on a biography written by Plutarch 200 years after her death. Early accounts of her life were given the anti-Cleopatra, pro-Roman slant promoted by Octavian. Other accounts of her life are mostly malicious, lack reliable sources, and were written centuries after her death. Careful historical analysis of her life and times has suggested that she was a highly competent ruler who skillfully navigated through a turbulent period of history surrounded by unstable neighbors. Politics more than sex seemed to be primary interest. Judith Thurman wrote in the The New Yorker, “Among the writers who actually met Cleopatra, Cicero said of her “I detest the Queen” and ridiculed Rome for its “fribbling, fawning” attraction to for her ; Nicolaus of Damascus, her children’s tutor, defected to her archrival Herod, and then to Octavian. Of first-century writers, Josephus, a Jewish historian writing for a Roman audience, based his account on Nicolaus’s; Plutarch, Antony’s biographer, had access to some firsthand testimony, but admitted to cherry-picking. Suetonius and Appian, historians of the second century, and prolific Dio, of the third, have been flagged for complacency in their errors and biases. Theirs and many other ancient texts exist only in fragments. What survives of them, two thousand years after Cleopatra’s death, is still the primary source for biographers. [Source: Judith Thurman, The New Yorker November 15, 2010]

Cleopatra on a coin Roller’s “Cleopatra,” part of a series of brief lives on Women in Antiquity, Thurman wrote, gives a rich account of late Ptolemaic culture, and surveys the Queen’s history in under two hundred pages. Roller is a professor emeritus of Greek and Latin at Ohio State University, so he had access to the ancient sources in their original languages, as well as to the scholarly literature in German and French. His voice is donnish and impartial, albeit a bit flat, like the daylight in his black-and-white photographs of modern Tarsus and Jericho, and his assertion that one really can’t hope to know Cleopatra. This volume should appeal to readers who prefer an aerial view of the subject to the seething congestion of its ring roads. Goldsworthy is a distinguished biographer of Julius Caesar, and his somewhat mistitled entrant to the lists, “Antony and Cleopatra” (Yale; $35), is a four-hundred-page work of Roman military and political history. Whether we like it or not, biographers bring their experience as men or women to their task. Roller and Goldsworthy both seem determined to resist the temptations of a siren, as if she might corrupt their integrity.

Schiff won the Pulitzer Prize for her 1999 biography, “Véra (Mrs. Vladimir Nabokov): Portrait of a Marriage”. Angelina Jolie is slated to play Cleopatra in a forthcoming 3-D bio-pic, possibly to be directed by James Cameron based on Stacy Schiff’s biography. On the biography, Thurman wrote, “Schiff relies on the same venerable Cleophobes, and exercises the same caution about them. Imaginative attunement with a subject, however, does not have to compromise a vigilant biographer’s critical detachment, and Schiff’s beautiful writing hums with that tension. This is her fourth ambitious life. It is an edifice of speculation and conjecture — like every “Cleopatra” ever written. But unlike nearly all of them it is a work of literature.”

Cleopatra and Her Family

Ptolemy XII Cleopatra was actually Cleopatra VII. She was not Egyptian and probably didn't even possess any Egyptian blood; she was the daughter of a Macedonian Greek king, Ptolemy XII, who ruled Egypt and was a descendant of one of Alexander the Great's generals. Cleopatra is Greek for “glory to her race.” Some African-American groups claim that Cleopatra was a black woman. There is this little evidence to back this up. However Ptolemy XII had a mysterious concubine who could have been black and could have given birth to Cleopatra although it is very unlikely.

Ptolemy XII was as known the “Flute Player” because of his musical talent and his ability to charms the ladies — and the boys — with his playing and his taste for things he liked to stick in his mouth. Cleopatra’s great-grand father was known as Ptolemy Physkon (“Potbelly”). He reportedly paraded around in flimsy robes to show off his flab (at that time regarded as sign of wealth).

Ptolemy XII's Egypt was still rich but it was becoming undermined by an unhappy local population, threatened by its rivals, and robbed by Roman moneylenders. Once while Ptolemy XII was in Rome his eldest daughter Tryphanena seized the throne. After she was assassinated the secondary daughter Berenike grabbed it. When Ptolemy returned he retook the throne with Cleopatra's help and Berenike was executed. Tryphanena and Berenike were Cleopatra’s elder sisters or half sisters.

Cleopatra's Early Life

Cleopatra VI was born in 69 B.C. She was the second or third of five or six children of Ptolemy XII and his wife and sister Cleopatra V. Her grandmother may have been a concubine. Er mother was her father’s full sister or perhaps an Egyptian of the local aristocracy. It is assumed she was educated as Ptolemaic princess in her time with instructions im literature, mathematics, philosophy, music, medicine and the martial arts.

In 51 B.C., after her father died, Cleopatra married her 10-year-old brother, Ptolemy XIII and the two of them became co-rulers of Egypt. Cleopatra was only 17. Cleopatra's marriage to her Ptolemy XIII was most likely unconsummated. After they took over the throne the Nile didn't flood and their was a famine. A eunuch named Pothinus was appointed regent for young Ptolemy and Cleopatra was driven out of Alexandria, resulting in a civil war.

Cleopatra's seized the Ptolemic throne with the help of Julius Caesar. Ptolemy XIII reportedly drowned in the Nile with a full suit of armor on. The circumstances behind the death were unclear. Caesar then arranged the marriage of Cleopatra and her younger brother Ptolemy XIV, whom was only 12 at the time and Cleopatra was able to dominate him

Cleopatra's Looks

Plutarch wrote: "Her beauty was not incomparable” but “the attraction of her conversation...was something bewitching...The persuasiveness of her discourse and her character...had something stimulating about it. It was a pleasure merely to hear her voice, with which, like an instrument of many strings, she could pass from one language to the next...Plato admits four sorts of flattery but she has a thousand." Another historian described her countenance as "alive rather than beautiful."

Plutarch wrote: "Her beauty was not incomparable” but “the attraction of her conversation...was something bewitching...The persuasiveness of her discourse and her character...had something stimulating about it. It was a pleasure merely to hear her voice, with which, like an instrument of many strings, she could pass from one language to the next...Plato admits four sorts of flattery but she has a thousand." Another historian described her countenance as "alive rather than beautiful."

Images close to her time contradict the notion that she a great beauty. The pictures of Cleopatra depicted on Roman coins shows a woman with a large hooked Semitic nose, sharp chin, boney face, narrow forehead and large eyes. Stacy Schiff wrote in her book Cleopatra: A Biography, “If the name is indelible, the image is blurry. She may be one of the most recognizable figures in history, but we have little idea what Cleopatra actually looked like. Only her coin portraits — issued in her lifetime, and which she likely approved — can be accepted as authentic.”

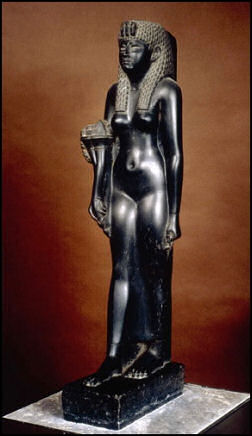

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: Her face has been immortalized on a handful of artifacts from the ancient world, including coins and a relief. Perhaps the best known depiction of her is a relief at Dendera temple in Egypt that shows her alongside her son Caesarion.The artifacts we have today are not numerous. They include coins minted of her that have been found at the site of Taposiris Magna in Egypt. There are a number of statues that may depict Cleopatra VII which are now located in museums scattered around the world. However, the provenance of these statues is uncertain and whether they really depict Cleopatra VII is debated. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, August 9, 2023]

The archaeological record doesn't leave us many clues, experts told Live Science. Her body has never been found, and depictions made at the time were likely not intended to be a true representation of her physical attributes. Andrew Kenrick, a visiting research fellow at the University of East Anglia in the U.K., said that ancient writers usually did not discuss what ancient figures looked like. Kenrick also noted that ancient statues can be misleading. "Sculptures and statues were intended as projections of various facets of a figure, rather than intended as a true likeness," Kenrick told Live Science. For instance, a sculpture may depict a ruler as being more muscular than they actually were.

Was Cleopatra Black

After a miniseries portrayed Cleopatra as black, there was some discussion about her skin color. Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: the archaeological record doesn't leave us many clues, experts told Live Science. Her body has never been found, and depictions made at the time were likely not intended to be a true representation of her physical attributes. "We simply do not have evidence from the ancient world that indicates Cleopatra's skin tone," Prudence Jones, a professor of classics and general humanities at Montclair State University, told Live Science. What's more, our conception of skin color as "white" or "Black" would have been foreign to the ancient people living at the time. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, August 9, 2023]

Additionally, we don't know the identity of Cleopatra's mother or paternal grandmother, Kenrick noted, which means it's possible Cleopatra could have had some African descent. "What we do know is that Cleopatra's father was Greek, and she would have considered herself to be Greek — although she did portray herself to be Egyptian, when it suited her politically," Kenrick said. At times the Ptolemies married within their own family and Cleopatra VII was married to her brother Ptolemy XIV before he was killed in 44 B.C.

However, Zahi Hawass, the former Egyptian antiquities minister, believes her Greek parentage points clearly to one answer. "Cleopatra was not Black," Hawass said in response to Adele James, a biracial actress, being cast to play the queen in the Netflix show "Queen Cleopatra." "As well documented history attests, she was the descendant of a Macedonian Greek general who was a contemporary of Alexander the Great. Her first language was Greek and in contemporary busts and portraits she is depicted clearly as being white," Hawass wrote in a column for Arab News at the time. Ultimately, Cleopatra's skin color isn't particularly important, Roller said.

Cleopatra's Sex Life and Reputation as a Seducer

The 2nd century Greek historian said that Cleopatra seduced men because she was "brilliant to look upon...with the power to subjugate everyone.” She would later become "a woman of insatiable sexuality and insatiable avarice" (Dio), "the whore of the eastern kings" (Boccaccio). She was a carnal sinner for Dante, for Dryden a poster child for unlawful love. A first-century A.D. Roman would falsely assert that "ancient writers repeatedly speak of Cleopatra's insatiable libido." Florence Nightingale referred to her as "that disgusting Cleopatra." Offering Claudette Colbert the title role in the 1934 movie, Cecile B. DeMille is said to have asked, "How would you like to be the wickedest woman in history?" [Source: Stacy Schiff, Smithsonian magazine, December 2010, Adapted from Cleopatra: A Biography, by Stacy Schiff.]

The 2nd century Greek historian said that Cleopatra seduced men because she was "brilliant to look upon...with the power to subjugate everyone.” She would later become "a woman of insatiable sexuality and insatiable avarice" (Dio), "the whore of the eastern kings" (Boccaccio). She was a carnal sinner for Dante, for Dryden a poster child for unlawful love. A first-century A.D. Roman would falsely assert that "ancient writers repeatedly speak of Cleopatra's insatiable libido." Florence Nightingale referred to her as "that disgusting Cleopatra." Offering Claudette Colbert the title role in the 1934 movie, Cecile B. DeMille is said to have asked, "How would you like to be the wickedest woman in history?" [Source: Stacy Schiff, Smithsonian magazine, December 2010, Adapted from Cleopatra: A Biography, by Stacy Schiff.]

Cleopatra reportedly had her first lover at twelve and built a temple where she kept male lovers drugged with performance boosters. She also purported had 100 lover in a single night, slept with her slaves, and heavily taxed or killed some men after the love-making was over. She learned many tricks it is said from courtesan at an Alexandria bordello. The Romans, who wanted to portray Cleopatra in the worst light possible light, were the source of many of these stories. In reality it is thought she spent much of her time sleeping alone and was busy managing her kingdom to indulge in too much debauchery. Her reputation a sex freak endured through the years. Obscene caricatures from the A.D. 1st century show a Cleopatra-like figure on a barge copulating with a crocodile. In famous 18th century European paintings she lies naked in a voluptuous pose on lion skins with an asp biting into her swelling bosom.

Cleopatra's Baths and Perfumes

Cleopatra, it is said, liked to bathe in freshly-squeezed ass milk or goat milk. She wrote her own book on cosmetics. One concoctions was made with burnt mice. She also reportedly used a perfume made from rose oil and violets on her hands and anointed her feet with an oil made with honey, cinnamon, iris, hyacinth and orange blossoms. Incense burners surrounded her throne.

Scientists believe they have uncovered what Cleopatra’s perfume smelled like after years of work. Madeline Buiano wrote in Martha Stewart Living: It started when archaeologists Robert Littman of the University of Hawaii and Jay Silverstein of the University of Tyumen uncovered the roughly 2,300-year-old remains of what is speculated to be a fragrance factory. The site, which the researchers began excavating in 2009, contains kilns and clay perfume containers, according to ScienceNews. [Source:Madeline Buiano, Martha Stewart Living, May 25, 2022]

Following the discovery, Berlin-based Egyptologist, Dora Goldsmith, and Prague-based professor of Greek and Roman philosophy, Sean Coughlin, tried to re-create a beloved Egyptian fragrance known as the Mendesian perfume, which Cleopatra may have used. The experts experimented with ingredients like desert date oil, myrrh, cinnamon, and pine resin to produce a scent that the pharaoh likely wore. According to Goldsmith and Coughlin, the perfume is a strong, but pleasant blend of spiciness and sweetness.

Cleopatra's Death

Antony's defeat spelled the end of Cleopatra' power. She placed her treasure of gold, silver, pearls and in a huge mausoleum with enough fuel to burn it down to keep her treasures from falling into Roman hands.. She then locked herself with her serving maids in her palace.

Cleopatra then reportedly tried to seduce to Octavian, but when she failed she chose to commit suicide at the age of 39 rather than face the humiliation of the rejection and being brought to Rome as a prisoner. She was found dead, one story goes, on a bed of pure gold, dressed in rich robes of Isis, with a message that she wanted to be buried in Rome with Antony.

In the meantime Antony, no doubt upset by the recent events, tried to commit suicide by falling on his sword. When he fell he missed his vital organs and remained alive for about a week before he died. He reportedly lived long enough to be hauled through a window in Cleopatra’s mausoleum where he is said to have died in Cleopatra's arms. In some accounts Antony was brought to the mausoleum on the first of August ten days or so before Cleopatra killed herself .

Octavian honored Antony’s will. Antony and Cleopatra were buried together (the location of grave site is a mystery). The Roman historian Dio Cassius reported that Cleopatra's body was embalmed as Antony's had been, and Plutarch noted that on the orders of Octavian, the last queen of Egypt was buried beside her defeated Roman consort. Sixteen centuries later Shakespeare proclaimed: "No grave upon the earth shall clip in it / a pair so famous." [Source: Chip Brown, National Geographic, July 2011]

With Cleopatra’s death in 30 B.C., the Ptolemaic Dynasty ended. Octavian lured Ptolemy Caesarian, Cleopatra’s son with Julius Caesar, back to Alexandria and had him murdered. Octavian adopted the children Cleopatra had with Antony. In 30 B.C. Egypt also became a province of Rome. It would not recover its autonomy until the 20th century.

Did Cleopatra Die From the Bite of the Horrible Asp

One of the famous stories of the Cleopatra legend is that she killed herself with the bite of an asp (a kind of poisonous snake) to her bosom. After the ruinous defeat at Actium in 31 B.C., Cleopatra was unable to continue the fight against Rome. Rather than witness the incorporation of Egypt into the Roman Empire, the story goes, she chose to die by the bite of the asp. The snake had reportedly been smuggled to her in a basket of figs after she was taken prisoner by Octavian. The asp was considered the minister of the sun god whose bite conferred not only immortality but also divinity.

Plutarch wrote that Cleopatra had experimented on condemned prisoners with various poisons and snake venoms, finding aspis venom to be the most painless of all fatal toxins. In Ptolemaic Egypt, the term "aspis" (an ancient Greek word referring to a wide variety of venomous snakes) was most likely an Egyptian cobra.

The cobra bite story has been questioned in recent years, namely because they are relatively large size snakes, making it difficult to hide one in a basket of figs and because Egyptian cobra venom is slow-acting and does not always cause death. Most historians regard the story as improbable at best. The poison from an asp causes excruciatingly pain and takes a while to kill someone. If she did kill herself with a snake it was probably with a cobra, whose venom is much more deadly and quick. In any case, no one ever saw the snake and reputed bite marks on her arm could have been scratches or mosquito bites.

Most likely Cleopatra consumed a poison she had hidden on her body. Plutarch saw Cleopatra's death certificate and wrote: "what took place is known to no one, since it was also said that she carried poison in a hollow comb...yet there was not so much as a spot found, or any symptoms of poison upon her body, nor was the asp seen within the monument."

See Egyptian cobras under VENOMOUS SNAKES IN THE MIDDLE EAST africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025