Home | Category: Late Dynasties, Persians, Nubians, Ptolemies, Cleopatra, Greeks and Romans

CLEOPATRA

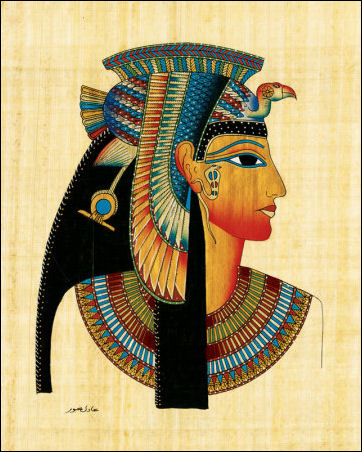

Cleopatra (Cleopatra VII, 69-30 B.C.) is one of the most famous women of all a time. A Greek Queen of Egypt, she played a major role in the extension of the Roman Empire and was a lover of Julius Caesar, the wife of Marc Antony and a victim of Augustus Caesar, the creator of the Roman Empire. [Source: Chip Brown, National Geographic, July 2011; Stacy Schiff, Smithsonian magazine, December 2010; Judith Thurman, The New Yorker, May 7, 2001 and November 15, 2010; Barbara Holland, Smithsonian, February 1997]

Cleopatra reigned from roughly 51-30 B.C. and was the last ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty, which ruled Egypt for nearly 300 years. Stacy Schiff wrote in her book “Cleopatra: A Biography”, “Cleopatra VII ruled Egypt for 21 years a generation before the birth of Christ. She lost her kingdom once; regained it; nearly lost it again; amassed an empire; lost it all.

A goddess as a child, a queen at 18, at the height of her power she controlled virtually the entire eastern Mediterranean coast, the last great kingdom of any Egyptian ruler. For a fleeting moment she held the fate of the Western world in her hands. She had a child with a married man, three more with another. She died at 39. Catastrophe reliably cements a reputation, and Cleopatra's end was sudden and sensational. [Source: Stacy Schiff, Smithsonian magazine, December 2010, Adapted from Cleopatra: A Biography, by Stacy Schiff.]

RELATED ARTICLES:

CLEOPATRA (69-30 B.C.): LOOKS, SEX LIFE, FAMILY AND DEATH africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CLEOPATRA'S LEGACY: CELEBRITY, ALLURE, SKIN COLOR africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SEARCH FOR CLEOPATRA'S TOMB africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MARC ANTONY: HIS LIFE, RELATIONS WITH CAESAR AND MILITARY CAMPAIGNS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OCTAVIAN AND MARK ANTONY AFTER CAESAR’S DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CLEOPATRA AND MARC ANTONY: ROMANCE, EVENTS, EXTRAVAGANCE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BATTLE OF ACTIUM europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OCTAVIAN AND DEATHS OF ANTONY, CLEOPATRA AND THEIR CHILDREN europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece and Rome: House of Ptolemy houseofptolemy.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/ Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu;Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ;History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame /web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Cleopatra: A Life” by Stacy Schiff (2010) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra” by Diane Stanley (1998) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra: the Last Queen of Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesly (2008) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra” by Michael Grant (2000, 1972) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra: Histories, Dreams and Distortions” by Lucy Hughes-Hallet (1990) Amazon.com;

“Women & Society in Greek & Roman Egypt” by Jane Rowlandson (1998) Amazon.com;

“Antony and Cleopatra” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Cleopatras: Discover the Powerful Story of the Seven Queens of Ancient Egypt!” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Memoirs of Cleopatra” by Margaret George (1997), Novel and Source of TV miniseries Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra's Daughter: A Novel” by Michelle Moran (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Last Dynasty: Ancient Egypt from Alexander the Great to Cleopatra” by Toby Wilkinson (2024) Amazon.com;

“Ptolemy I: King and Pharaoh of Egypt,” Illustrated, by Ian Worthington (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Last Pharaohs: Egypt Under the Ptolemies, 305–30 BC” by J. G. Manning (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Fall of Egypt and the Rise of Rome: A History of the Ptolemies” by Guy de la Bedoyere (2024) Amazon.com;

“Alexandria: The City that Changed the World” by Islam Issa (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

Cleopatra's Intelligence

Cleopatra was a woman of genius and a worthy opponent of Rome. During Cleopatra’s reign, Egypt again became a factor in Mediterranean politics. Her main preoccupations were to preserve the independence of Egypt, to extend its territory if possible, and to secure the throne for her children. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

Cleopatra could speak seven languages, according to Plutarch, and had a keen interests in science and literature. Cicero met her at Caesar’s house. Although he loathed her and regarded her as arrogant he admitted she was intelligent and was involved in "things that had to do with learning."

Cleopatra is said to have wrote treatises on alchemy, weights and measures and gynecology. The 10th century Arab historian Al-Masudi wrote many centuries after her death, she was "a princess well versed in the sciences, disposed to the study of philosophy and counted scholars among her intimate friends. She was the author of works on medicine , charms, and other divisions of the natural sciences. The books bear her name and were well known among men conversant with art and medicine.”

Cleopatra and Power

Kara Clooney, who wrote in a book about ancient Egyptian queens, wrote that Cleopatra combined brilliant leadership with a productive womb.”. She told National Geographic History: Growing up as a Ptolemy must have been a PTSD-inducing experience. Every Ptolemy son or daughter had their own entourage, their treasuries, their own sources of power and also shared power, but within a very exclusive system of siblings. And killed each other with impunity and regularity. My favorite Ptolemaic story is Cleopatra II, who was married to her brother. They got in a massive argument and the brother was killed. Then she married another brother. Her daughter, Cleopatra III, then ended up overthrowing her mother and taking up with her uncle, Cleopatra II’s brother, kicking the mother out into exile. The uncle then sent her (Cleopatra II) a package containing her own son, cut up into little bits, as a birthday present. Then they all get back together for political reasons. [Source Simon Worrall, National Geographic History, December 15, 2018]

Kara Clooney, who wrote in a book about ancient Egyptian queens, wrote that Cleopatra combined brilliant leadership with a productive womb.”. She told National Geographic History: Growing up as a Ptolemy must have been a PTSD-inducing experience. Every Ptolemy son or daughter had their own entourage, their treasuries, their own sources of power and also shared power, but within a very exclusive system of siblings. And killed each other with impunity and regularity. My favorite Ptolemaic story is Cleopatra II, who was married to her brother. They got in a massive argument and the brother was killed. Then she married another brother. Her daughter, Cleopatra III, then ended up overthrowing her mother and taking up with her uncle, Cleopatra II’s brother, kicking the mother out into exile. The uncle then sent her (Cleopatra II) a package containing her own son, cut up into little bits, as a birthday present. Then they all get back together for political reasons. [Source Simon Worrall, National Geographic History, December 15, 2018]

Cleopatra is probably the only woman in our story who uses her reproductive abilities like a man, to create a legacy. The other women are either ruling on behalf of a younger child or they’re ruling because there is no male offspring and are stepping in during years when they couldn’t produce any children. Cleopatra used her productive womb to have children with two Roman warlords. She had one child with Julius Caesar, three children with Mark Antony—twins, no less—and she survived it. She then carefully placed each child in charge of a different part of her growing Eastern Empire, in competition with the Western Roman Empire. If it weren’t for the boneheaded decisions made by Antony, the Roman warlord she was partnered with, we would maybe talk about her and her legacy differently.

She has come down to us as a great beauty, but we have to assume that she was partially a product of incest. And incest did not make people beautiful. I am thinking of Charles II’s giant head, how he needed special pillows and couldn’t chew. Cleopatra’s coinage doesn’t show her as a great beauty. What is written about her talks, rather, of her wit, conversation, and intelligence. Whatever it was that drew these Roman warlords to her, she used it. She used personal connections better than any of the other women in" Egypt. "Her name is synonomous with beauty and intrigue. Although her ambitions were never realized, she has achieved immortality through her personal story of love and tragedy.

Egypt and Rome at the Time Cleopatra Became Leader

Stacy Schiff wrote in her book Cleopatra: A Biography, Cleopatra “and her 10-year-old brother assumed control of a country with a weighty past and a wobbly future. The pyramids, to which Cleopatra almost certainly introduced Julius Caesar, already sported graffiti. The Sphinx had undergone a major restoration — more than 1,000 years earlier. And the glory of the once-great Ptolemaic empire had dimmed. [Source: Stacy Schiff, Smithsonian magazine, December 2010, Adapted from Cleopatra: A Biography, by Stacy Schiff.]

Cleopatra took the throne of Egypt at a time when Egypt was the richest place in the Middle East. But at the same time the Ptolemaic empire was crumbling. Chip Brown wrote in National Geographic, The lands of Cyprus, Cyrene (eastern Libya), and parts of Syria had been lost; Roman troops were soon to be garrisoned in Alexandria itself. Still, despite drought and famine and the eventual outbreak of civil war, Alexandria was a glittering city compared to provincial Rome. Cleopatra was intent on reviving her empire, not by thwarting the growing power of the Romans but by making herself useful to them, supplying them with ships and grain, and sealing her alliance with the Roman general Julius Caesar with a son, Caesarion. [Source: Chip Brown, National Geographic, July 2011]

Schiff wrote: “Over the course of Cleopatra's childhood Rome extended its rule nearly to Egypt's borders. The implications for the last great kingdom in that sphere of influence were clear. Its ruler had no choice but to court the most powerful Roman of the day?a bewildering assignment in the late Republic, wracked as it was by civil wars...Cleopatra's father had thrown in his lot with Pompey the Great. Good fortune seemed eternally to shine on that brilliant Roman general, at least until Julius Caesar dealt him a crushing defeat in central Greece. Pompey fled to Egypt, where in 48 B.C. he was stabbed and decapitated. Twenty-one-year-old Cleopatra was at the time a fugitive in the Sinai — on the losing side of a civil war against her brother and at the mercy of his troops and advisers. Quickly she managed to ingratiate herself with the new master of the Roman world.

Meanwhile the Roman civil wars raged on, as tempers flared between Mark Antony, Caesar's protégé, and Octavian, Caesar's adopted son. Repeatedly the two men divided the Roman world between them. Cleopatra ultimately allied herself with Antony, with whom she had three children; together the two appeared to lay out plans for an eastern Roman empire. Antony and Octavian's fragile peace came to an end in 31 B.C., when Octavian declared war — on Cleopatra. He knew Antony would not abandon the Egyptian queen. He knew too that a foreign menace would rouse a Roman public that had long lost its taste for civil war. The two sides ultimately faced off at Actium, a battle less impressive as a military engagement than for its political ramifications. Octavian prevailed. Cleopatra and Antony retreated to Alexandria. After prolonged negotiation, Antony's troops defected to Octavian.

How Cleopatra became the Ruler of Egypt

Juan Pablo Sánchez wrote in National Geographic History: Cleopatra’s father, Ptolemy XII, named his two oldest children, 18-year-old Cleopatra and 10-year-old Ptolemy XIII, as co-heirs. They would serve together under the guardianship of Rome. Because Egypt had become a Roman protectorate during the elder Ptolemy’s rule, Romans had a say in who would be ruling Egypt. [Source Juan Pablo Sánchez, National Geographic History, October 16, 2020]

Cleopatra emerges from a carpet

standing before Caesar After their father’s death in 51 B.C., Ptolemy and his sister were symbolically wed, but there was no love between them, familial or otherwise. The Ptolemaic kings and queens had a long family tradition of competing for the throne: sibling against sibling or parent against child. Two years later, Ptolemy’s advisers tried to move against Cleopatra to make the young boy the sole ruler.

As the two Egyptian siblings were squabbling over their throne, Rome was in the middle of its own power struggle. Two of its great military heroes, Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great, were engaged in a civil war and were looking for alliances. Pompey needed Egypt and decided to back Ptolemy XIII over his sister, who went into exile. Far from the capital, Cleopatra established her own base of operations where she raised an army and bided her time.

In the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 B.C., Caesar defeated Pompey, who fled to Alexandria. In a reversal, the young Ptolemy had Pompey executed and presented his head to Julius Caesar when he swept into Egypt later that year. Caesar was saddened and disgusted: Ancient historian Plutarch wrote in the first century A.D. how Caesar had “turned away in horror [when] presented the head of Pompey, but he accepted Pompey’s seal-ring, and shed tears over it.”

This gross miscalculation on the young pharaoh’s part was a prime opportunity for Cleopatra and her forces. She smuggled herself into Alexandria for a meeting with Caesar and won him to her cause. He supported her claim to the throne, sparking an uprising of Ptolemy’s supporters who were defeated. The young king was killed, and Caesar placed the 21-year-old Cleopatra VII on the throne. She would co-rule, in name, with a younger brother, Ptolemy XIV. To consolidate the alliance, Cleopatra invited Caesar, 30 years her senior, to stay in Egypt with her.

Cleopatra and Julius Caesar

Cleopatra had a fling with Julius Caesar and had a son with him called Caesarion. After Caesar became the dictator of Rome he arrived in Egypt during the civil war between Cleopatra and her brother. Caesar came to claim the debts Egypt owed Rome and Cleopatra saw in him a chance to win back her kingdom and expand it into Syria, Palestine and Asia Minor. Her alliance with Caesar seems to have been strategic, romantic and sexual. For his part Caesar made little mention of Cleopatra in his account of the Alexandrine wars.

Caesar initially didn't want to have anything to do with Cleopatra but he was delayed in his return to Rome by unfavorable winds. According to Plutarch’s version of events she had herself rolled up in bedsheets and delivered to Caesar, who was so besotted with her he orchestrated a reconciliation between Cleopatra and her brother and then had Ptolemy kill his former partner Pothinus. Pliny is said to be the source the rolled-up-in-bedsheets story. Many doubt its veracity. In the 1963 film “Cleopatra” Elizabeth Taylor’s Cleopatra spills out of Persian carpet at the feet of Caesar ready to crawl up his legs.

When Cleopatra met up with Caesar he was a balding epileptic with a lot of experience with women. He was 32 years older than her and married. The two of them sailed down the Nile together in a 300-foot barge with gardens and banquet rooms. In 47 B.C., Cleopatra gave birth to Caesar’s son, Ptolemy Caesarian (“Little Caesar”) . To honor the event she had a coin minted showing her as Aphrodite nursing Eros.

For two months Cleopatra entertained Caesar, with her charms and those of Egypt. Plutarch wrote: Caesar “often feasted with her until dawn; and they would have sailed together . . . to Ethiopia.” By the time Caesar left Egypt, Cleopatra was pregnant. She gave birth to a boy in 47 B.C. and openly proclaimed Julius Caesar the father. Egyptian priests began to teach that the god Amun had incarnated himself in the person of Caesar, the most powerful man in the world at the time, to father the baby prince. [Source Juan Pablo Sánchez, National Geographic History, October 16, 2020]

Roman support of Cleopatra's armies won her full control of Egypt. She married her other little brother Ptolemy XIII and then poisoned him after Little Caesar was born. Her teenage sister, Arisnoe, who had tried to dethrone, was paraded in Rome in golden shackles but at leaste she was allowed to live in exile (at least until later one when Cleopatra persuaded Antony to have her dragged from her temple and put to death).

See Separate Article: JULIUS CAESAR’S LIFE AND CHARACTER europe.factsanddetails.com

Julius Caesar Helps Cleopatra Seize the Egyptian Throne

Caesar giving Cleopatra

the Throne of Egypt Caesar arrived in Alexandria days after Pompey's murder. He barricaded himself in the Ptolemies' palace, the home from which Cleopatra had been exiled. From the desert she engineered a clandestine return, skirting enemy lines and Roman barricades, arriving after dark inside a sturdy sack. Over the succeeding months she stood at Caesar's side — pregnant with his child — while he battled her brother's troops. With their defeat, Caesar restored her to the throne.

Judith Thurman wrote in The New Yorker the morning after Cleopatra finagled her way into Caesar’s stronghold “her brother dashed into the streets and nearly persuaded a mob to rise against the usurpers.Caesar's Praetorians dragged him back inside, but his handlers rallied their forces...In the ensuing wars against Caesar and Cleopatra, which the world’s greatest general nearly lost (until reinforcements arrived, he was severely shorthanded), Ptolemy drowned. The victors celebrated with a leisurely Nile cruise, a visit to the pyramids, and some whistlestopping in the heartland. The public honeymoon demonstrated an inspired gift for mixing business with pleasures, and both with stagecraft.” [Source: Judith Thurman, The New Yorker November 15, 2010]

Giving birth to Caesar’s son, Thurman wrote, “consolidated her bands with his father, and with her own people and their priests, who rejoiced at a male heir. With a son as her symbolic co-regent and caesar as her protector, Cleopatra had no need to remarry. She henceforth governed alone — uniquely so among female monarchs of her period. Her autonomy depended on the fickle good will of Rome, and her exchange of favors with two Roman leaders.

Cleopatra in Rome

With things under control at home, Cleopatra went to Rome with Caesar. In Rome, she lived in one of Caesar’s suburban palaces and impressed some with her wit and turned off others with her arrogance. Her presence in Rome caused quite stir and triggered a fad for anything associated with Egypt. Many women adopted Cleopatra’s “melon” hairstyle (rows of tight briads gathered in a low bun). Caesar and Cleopatra hosted great parties. The Roman leader even raised a golden statue to her in the temple of Venus. Even so Cleopatra was not well liked by powerful people like Cicero and her claim to any power was tied to Caesar.

Juan Pablo Sánchez wrote in National Geographic History: At the end of 46 B.C., Cleopatra visited Rome at Caesar’s invitation, bringing Caesarion and all the royal pageantry of her court. Plutarch wrote that Caesar “would not let her return to Alexandria without high titles and rich presents. He even allowed her to call the son whom she had borne him by his own name.” Caesar welcomed Cleopatra and her family in one of his suburban villas, the Horti Caesaris, showering her with official honors. [Source Juan Pablo Sánchez, National Geographic History, October 16, 2020]

Many Romans remarked that the child looked markedly like Julius Caesar. Mark Antony, Caesar’s lieutenant, told the Senate that Caesar had acknowledged to his closest friends that Caesarion was indeed his son. If Cleopatra’s claims were believed, Caesarion was Caesar’s only surviving child. His daughter, Julia, who had been married to Pompey, died in childbirth in 54 B.C.

Despite the cool reception from the Roman people, Julius Caesar was optimistic about the relationship between Rome and Egypt. He erected a statue of Cleopatra in the Temple of Venus Genetrix. This era marked what Caesar saw as the beginning of an ambitious imperial project. Rumors spread that he was even mulling a transfer of the imperial capital to Alexandria. (For most Romans, becoming a citizen was the path to power.)

Cleopatra after Caesar

Cleopatra from the Ruins of Dendera

On the Ides of March in 44 B.C., as Caesar was making plans to marry Cleopatra and legitimize their child, he was assassinated. This was a clear setback for Cleopatra's larger ambitions. Caesar’s great-nephew Octavian was named his heir not Ptolemy Caesarian.

Juan Pablo Sánchez wrote in National Geographic History: Caesar never acknowledged Caesarion as his heir and instead had written in his will that his great-nephew, Gaius Octavius (Octavian), was his heir. Cleopatra and Caesarion were in Rome when Caesar was killed. Realizing that their lives were in danger, Cleopatra decided to return to Egypt immediately.[Source Juan Pablo Sánchez, National Geographic History, October 16, 2020]

As soon as she arrived back in Alexandria, the queen moved to consolidate her power. Sources say she had her brother and co-ruler, Ptolemy XIV, poisoned and then appointed her toddling son as her co-regent. From this point, Caesarion was officially recognized as Ptolemy XV Caesar.

In Rome Octavian refused to recognize the lineage of Egypt’s young co-regent. With calculated timing, the late Julius Caesar’s right-hand man and confidante Gaius Oppius published a book in which he claimed that Caesarion was not the son of Caesar at all. It was a warning to Cleopatra to tread carefully with the new masters of Rome.

Cleopatra as a Leader

Cleopatra ascended to the throne in 51 B.C. at age 18. She ruled for 21 years. In that time she survived revolts and exile, showed superb diplomatic skills and used divine mandate and patronage to keep a firm grip on power. She shrewdly formed an alliance with the priesthood, who promoted her cult as mother goddess, and used delaying tactics on important decisions to avoid making mistakes. The simple fact that she lasted as long as did at a time of great upheaval and change is testimony enough of her ability as a leader.

Stacy Schiff wrote in her book Cleopatra: A Biography, “A capable, clear-eyed sovereign, she knew how to build a fleet, suppress an insurrection, control a currency. One of Mark Antony's most trusted generals vouched for her political acumen. Even at a time when female rulers were no rarity, Cleopatra stood out, the sole woman of her world to rule alone. She was incomparably richer than anyone else in the Mediterranean. And she enjoyed greater prestige than every other woman of her time, as an excitable rival king was reminded when he called for her assassination during her stay at his court. (The king's advisers demurred. In light of her stature, they reminded Herod, it could not be done.) Cleopatra descended from a long line of murderers and upheld the family tradition, but was for her time and place remarkably well behaved. [Source: Stacy Schiff, Smithsonian magazine, December 2010, Adapted from Cleopatra: A Biography, by Stacy Schiff.]

“Her tenure alone speaks to her guile. She knew she could be removed at any time by Rome, deposed by her subjects, undermined by her advisers — or stabbed, poisoned and dismembered by her own family. In possession of a first-rate education, she played to two constituencies: the Greek elite, who initially viewed her with disfavor, and the native Egyptians, to whom she was a divinity and a pharaoh. She had her hands full. Not only did she command an army and navy, negotiate with foreign powers and preside over temples, she also dispensed justice and regulated an economy. Like Isis, one of the most popular deities of the day, Cleopatra was seen as the beneficent guardian of her subjects. Her reign is notable for the absence of revolts in the Egyptian countryside, quieter than it had been for a century and a half.” [Ibid]

A sample of Cleopatra’s handwriting exists on two fragments of papyrus featured in an exhibit on Cleopatra at Philadelphia’s Franklin Museum in 2010. The documents with the Greek inscription “make it happen” refers to a tax break for a friend of Mark Antony. The documents and 150 other artifacts were found during an intensive search for her tomb in the Egyptian town of Taposiris Magnas and the submerged ancient cities of Heracleion and Canopus, where earthquakes and tidal waves destroyed Cleopatra’s palace. Also on display at the exhibit entitled “Cleopatra — the Search for the Last Queen of Egypt — were gold necklaces, bracelets, a sculpture of the son of Cleopatra and Julius Caesar and sling shot bullets that may have been used by Roman armies to claim Egypt after Cleopatra’s death in 30 B.C.

Cleopatra introduced a tax on beer — which ancient Egyptians preferred to wine — to finance her wars with Rome. As Jason Lambrecht has put it, “this was so outrageous to Egypt, that it would compare to a tax on water today. ” [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, March 6, 2021]

Cleopatra and Ancient Egyptian Traditions

Cleopatra as Isis “Lest her subjects resent her Roman overtures,” Brown wrote, “Cleopatra embraced Egypt's traditions. She is said to have been the first Ptolemaic pharaoh to bother to learn the Egyptian language. While it was politic for foreign overlords to adopt local deities and appease the powerful religious class, the Ptolemies were genuinely intrigued by the Egyptian idea of an afterlife. Out of that fascination emerged a hybrid Greek and Egyptian religion that found its ultimate expression in the cult of Serapis — a Greek gloss on the Egyptian legend of Osiris and Isis.”

“One of the foundational myths of Egyptian religion, the legend tells how Osiris, murdered by his brother Seth, was chopped into pieces and scattered all over Egypt. With power gained by tricking the sun god, Re, into revealing his secret name, Isis, wife and sister of Osiris, was able to resurrect her brother-husband long enough to conceive a son, Horus, who eventually avenged his father's death by slaughtering uncle Seth. By Cleopatra's time a cult around the goddess Isis had been spreading across the Mediterranean for hundreds of years. To fortify her position, and like other queens before her, Cleopatra sought to link her identity with the great Isis (and Mark Antony's with Osiris), and to be venerated as a goddess. She had herself depicted in portraits and statues as the universal mother divinity...She appeared in the holy dress of Isis at a festival staged in Alexandria to celebrate Antony's victory over Armenia in 34 B.C., just four years before her suicide and the end of the Egyptian empire.”

Caesarion — Cleopatra’s Son with Caesar

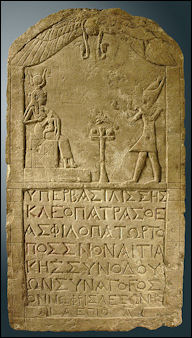

Juan Pablo Sánchez wrote in National Geographic History: The earliest existing depictions of Caesarion appear on coins minted in Cyprus in 44 B.C. Even though the boy was then a toddler, he was still shown as a baby in his mother’s arms. There are later works of art in which Caesarion appears as a young man, wearing the typical Egyptian headdress (nemes) and kilt (shandyt), as in traditional images of the pharaohs. [Source Juan Pablo Sánchez, National Geographic History, October 16, 2020]

Many representations of Caesarion associate him with the Egyptian god Horus, the son of Isis and Osiris. After Osiris is violently murdered by his rival Set, Isis must protect her son and restore the rightful king to the throne. Cleopatra smartly used this imagery to win support for Caesarion and cast herself in the role of divine maternal protector.

Caesarion’s fortunes were revived in 42 B.C. when Mark Antony arrived in Egypt as Roman triumvir in charge of the eastern provinces. He was seeking a way to bring down fellow triumvir Octavian, and in 41 B.C. he summoned Cleopatra to Tarsus. The queen navigated this important meeting just as carefully as her first with Julius Caesar.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2024