Home | Category: New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut)

HATSHEPSUT'S RULE

Queen Hatshephut

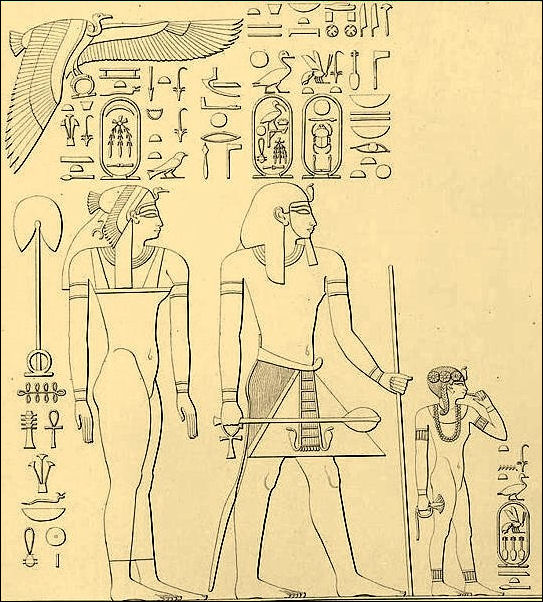

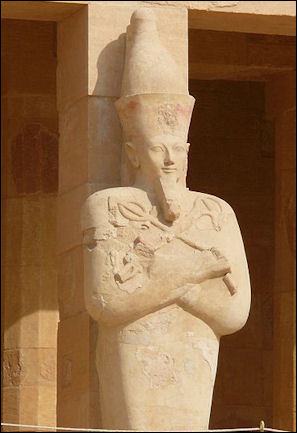

with a beard Hatshepsut (ruled 1479 to 1458 B.C.) was the Queen of Egypt during the 18th Dynasty. The daughter of Thutmose I, she married Thutmose II. When he ascended to the throne she became the real ruler. When he died she acted as regent for his son, Thutmose III, then had herself crowned as Pharaoh. Maintaining the fiction that she was a male, she was represented with the regular pharaonic attributes, including a beard. [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003; [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Hatshepsut was one of the few women in Egyptian history to hold such a high position and is particularly noteworthy for holding on to power for so long. Reigned during one of ancient Egypt’s golden ages, when wealth poured from a relatively large empire, she oversaw the construction of monumental works all over the state, including numerous temples and shrines and four giant obelisks at the Temple of Amun at Karnak. A myriad of artworks celebrating her accomplishments and immortalizing her prayers were also made. Hatshepsut built a magnificent funerary temple at Deir el-Bahri on the west bank of the Nile at Thebes and sent a large commercial expedition to the land of Punt, in modern Ethiopia.[Source: David Rull Ribó, National Geographic, March 7, 2024]

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “Hatshepsut dressed as a king, even affecting a false beard, but it was never her intention to pass herself off as a man; rather, she referred to herself as the “female falcon.” Her success was due, at least in part, to the respect of the people for her father’s memory and the loyal support of influential officials who controlled all the key positions of government. [Source :Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

On why she admires Hatsheput so much, Kara Clooney, who wrote in a book about ancient Egyptian queens, told National Geographic History: She left Egypt better than she found it! She put Egypt and her dynasty onto a secure footing and created the next king, Thutmose III, who ended up being the Napoleon of Egypt, enlarging its empire beyond anything it had ever seen. She was very canny in how she used ideology to set herself up with unassailable power. She told her people: “The God has chosen me, it’s not my own ambition, it’s not my own wish but my father, the God Amon-Re has spoken to me and told me that I must do this.” [Source Simon Worrall, National Geographic History, December 15, 2018]

The reason I’m so drawn to Hatshepsut is because she did everything so perfectly, which is something that is idealized. Success is very fungible. It’s something that someone else can claim and take credit for. Her name can easily be removed from a set of reliefs showing her building obelisks or sending expeditions to the land of Punt, and another name put in her place. Failure, on the other hand, is not abstract. It involves suicide with asps or naval battles where everything goes horribly wrong. It’s something that is very individualized. Thus, we remember Cleopatra. Shakespeare wrote a play about her. But Hatshepsut we must resurrect from the ashes of history and investigate why female success is so easily ignored, while female failure is so beautifully aggrandized.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

”Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh” by Joyce A. Tyldesley (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Woman Who Would Be King” by Kara Cooney (2014) Amazon.com;

“Hatchepsut: The Life of the Female Pharaoh (1507 - 1458 BCE 18th Dynasty)”

by Ron Schaefer Amazon.com;

“Thutmose III and Hatshepsut, Pharaohs of Egypt: Their Lives and Afterlives” by Aidan Dodson (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Mystery of the Land of Punt Unravelled” (2015) by Ahmed Ibrahim Awale Amazon.com;

“Seafaring Expeditions to Punt in the Middle Kingdom” by Kathryn Bard and Rodolfo Fattovich (2018) Amazon.com;

“When Women Ruled the World: Six Queens of Egypt” by Kara Cooney (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Temple of Hatshepsut, the Solar Complex (Deir El-bahari, 6) by Janusz Karkowski (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Southern Room of Amun in the Temple of Hatshepsut: History and Epigraphy: With an Appendix Multidisciplinary Project” by Izabela Uchman (Deir El-bahari, 10)

by Katarzyna Kapiec (2023) Amazon.com;

“Guide To The Temple Of Deir El Bahari” (1894-5) Amazon.com;

“The Cleopatras: Discover the Powerful Story of the Seven Queens of Ancient Egypt!” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (2024) Amazon.com;

“King and Goddess” by Judith Tarr (1996), Novel Amazon.com;

“Child of the Morning” by Pauline Gedge (1976) Novel Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom" by Joyce Tyldesley (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume III: From the Hyksos to the Late Second Millennium BC” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East” by Amanda H Podany (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Temples, Tombs, and Hieroglyphs: A Popular History of Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz (1978, 2009) Amazon.com;

Hatshepsut Seizes the Throne

Hatshepsut ruled Egypt, first as co-regent and then as pharaoh, for a total of 21 years. She initially rose to power as the regent for her stepson Thutmose III (d. 1450 B.C.), then a minor. In 1503 B.C., she crowned herself pharaoh, declaring it the will of heaven that she rule even after her stepson came of age. According to the Gale Encyclopedia of World History: The fiction of corule with Thutmose III was never abandoned, but his service in the priesthood of Amun, an assignment Hatshepsut undoubtedly arranged, effectively removed him from power until her death. In concert with her talented, handpicked subordinates, she concentrated on economic development and trade, and under her rule Egypt’s wealth grew steadily. [Source: Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments, Thomson Gale, 2008]

Not content with being the power behind the throne, Hatshepsut proclaimed herself pharaoh, while serving as regent for Thutmose III. Tyldesley wrote for the BBC: “For a couple of years Hatshepsut behaved as a totally conventional regent, acknowledging the young Thutmose III as the one and only pharaoh. Then, with no explanation, she was crowned king. Hatshepsut now took precedence over her stepson, and Thutmose was relegated to the background. He would languish in obscurity for some 20 years. From this point onwards, Hatshepsut enjoyed a conventional reign. Military campaigns were scarce; it seems that few enemies were prepared to challenge pharaoh's might..... When she died, after 22 years on the throne, Hatshepsut was buried with all due honour alongside her father in the Valley of the Kings. [Source: Dr Joyce Tyldesley, University of Manchester, BBC, February 17, 2011]

To support her cause, Hatshepsut claimed that the god Amun had taken the form of her father and visited her mother, and she herself was the result of this divine union. As the self-proclaimed daughter of God, she further justified her right to the throne by declaring that the god Amun-Ra had spoken to her, saying, “Welcome my sweet daughter, my favorite, the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Maatkare, Hatshepsut. Thou art the king, taking possession of the Two Lands.” [Source :Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Thutmose III and Hatshepsut

In 2016, Egypt's Ministry of Antiquities and German Archaeological Institute announced the discovery of blocks that likely belonged to one of her buildings Egypt's Elephantine Island near Aswan that provides insight into her early years as a pharaoh. Elahe Izadi wrote in the Washington Post, “Early in her career, Hatshepsut was depicted as a woman, but later on her likeness was of a powerful, muscular ruler who had the same false beard that male pharaohs would wear.” The blocks found near Aswan are different. “Believed to have been part of a waystation for the deity, Khnum, several of the blocks show Hatshepsut as a woman."The building must therefore have been erected during the early years of her reign, before she began to be represented as a male king," the antiquities ministry said. "Only very few buildings from this early stage of her career have been discovered so far." [Source: Elahe Izadi, Washington Post, April 23 2016]

“At first, Hatshepsut acted on her stepson's behalf, careful to respect the conventions under which previous queens had handled political affairs while juvenile offspring learned the ropes. But before long, signs emerged that Hatshepsut's regency would be different. Early reliefs show her performing kingly functions such as making offerings to the gods and ordering up obelisks from red granite quarries at Aswan. ...As Thutmose III grew up, Hatshepsut's depiction changed. As Smithsonian Magazine noted, "the formerly slim, graceful queen appears as a full-blown, flail-and-crook-wielding king, with the broad, bare chest of a man and the pharaonic false beard."”

See Separate Article: HATSHEPSUT (1479 TO 1458 B.C.): HER FAMILY, LIFE AND REIGN africame.factsanddetails.com

Why Did Hatsheput Usurp the Throne from Thutmose III?

Why did Hatsheput usurp the throne from Thutmose III? Joyce Tyldesley of the University of Manchester wrote for the BBC: What could have caused her to take such unprecedented action? Legally, there was no prohibition on a woman ruling Egypt. Although the ideal pharaoh was male-a handsome, athletic, brave, pious and wise male-it was recognised that occasionally a woman might need to act to preserve the dynastic line. When Sobeknofru ruled as king at the end of the troubled 12th Dynasty she was applauded as a national heroine. Mothers who deputised for their infant sons, and queens who substituted for husbands absent on the battlefield, were totally acceptable. What was never anticipated was that a regent would promote herself to a permanent position of power. [Source: Dr Joyce Tyldesley, University of Manchester, BBC, February 17, 2011] “Morally Hatshepsut must have known that Thutmose was the rightful king. She had, after all, accepted him as such for the first two years of his reign. We must therefore deduce that something happened in year three to upset the status quo and to encourage her to take power. Unfortunately, Hatshepsut never apologises and never explains. Instead she provides endless justification of her changed status, claiming on her temple walls (falsely) that both her earthly father Thutmose and her heavenly father, the great god Amen, intended her to rule Egypt. She goes to a great deal of trouble to appear as a typical pharaoh, even changing her official appearance so that her formal images now show her with the stereotyped king's male body, down to the false beard. Hatshepsut has realised that others will eventually question her actions, and is carving her defence in stone. |::|

“What are we to make of Hatshepsut's actions? It is too simplistic to condemn her as a ruthless power-seeker. She could not have succeeded without the backing of Egypt's elite, the men who effectively ruled Egypt on behalf of the king, so they at least must have recognised some merit in her case. Her treatment of Thutmose is instructive. While the boy-king lived he was a permanent threat to her reign yet, while an 'accidental' death would have been easy to arrange, she took no steps to remove him. Indeed, seemingly oblivious to the dangers of a coup, she had him trained as a soldier. |::|

“It seems that Hatshepsut did not fear Thutmose winning the trust of the army and seizing power. Presumably, she felt that he had no reason to hate her. Indeed, seen from her own point of view, her actions were entirely acceptable. She had not deposed her stepson, merely created an old fashioned co-regency, possibly in response to some national emergency. The co-regency, or joint reign, had been a feature of Middle Kingdom royal life, when an older king would associate himself with the more junior partner who would share the state rituals and learn his trade. As her intended successor, Thutmose had only to wait for his throne; no one could have foreseen that she would reign for over two decades.”|::|

Queen Hatshepsut’s Rule

Queen Hatshepsut took power from Thutmose III and attained unprecedented power for a woman. She ruled for 21 years (from 1479 B.C. to 1473 B.C. as the regent of Thutmose III and 1473 B.C. to 1458 B.C. as Pharaoh and co-ruler with Thutmose III). Her father, Thutmose II, did not rule for long. When he died Thutmose III was just a boy and Hatshepsut was named his regent and took effective control of the kingdom. Early on she seemed to play her role as expected. She was careful to respect convention and did not overstep her herself. The earliest reliefs depict her as a queen standing by Thutmose III, who is portrayed as an adult king performing pharaonic duties.

But as time went on Hatshepsut became bolder. Early reliefs after Thutmose II’s death show her making offering to the gods and ordering an obelisk from Aswan. Within a few years she assumed the role of “king” and relegated her stepson to second-in-command. It is not clear what her motive was. Some have suggested it was a hunger for power. Other have said it was an effort to reinstate royal blood — and the divinity associated with it — to the ruling dynasty. Yet others say she took power to avoid a palace coup brewing while her stepson was still too young to act. During Hatsheput’s rule, the Egyptian economy expanded and trade flourished. She dispatched a major sea-borne expedition to Punt (Somalia) on the African coast and the southern part of the Red Sea. The walls her mortuary temple at Deir el Bahri are illustrated with a colorful account of expedition to Punt. There are images of ships, a marching army led by her general, Nehsi. Based on drawings, expedition brought back gold, ebony, animal skins, baboons, and refined myrrh as well as living myrrh trees that were then planted around the temple. The walls at Deir el Bahri also depict the houses seen in Punt and an image of its obese queen. [Source :Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Queen Hatshephut and Thutmose I's family

Queen Hatshepsut led the expedition to Punt (Somalia) and is thought to have led a military campaign into Nubia (Sudan). Overall though she presided over an extended period of peace and prosperity and helped Egypt get back on its feet in the wake of a string of military campaigns fought by her predecessors. Under Hatshepsut’s rule trade blossomed as timber poured in from Lebanon, turquoise mining was stepped up the Sinai and luxuries such as gold, ivory, spices, ebony, myrrh, panther skins and live baboons came in from Punt and Africa. Egypt became rich. The gold that was used in the making of the tomb of King Tutankhamun was accumulated during Hatshepsut’s reign.

There is also some evidence that Hatshepsut embraced “the common people” and this may have been the key to her lasting as long as she did. A word that pops up time and again in her hieroglyphic text is “rekhyt” — a common Nile marsh bird associated with ordinary people. Egyptologist Kenneth Griffin of Swansea University in Wales told National Geographic, “her inscriptions seemed to show a personal association with the rekhyt which at this stage is unrivaled.”

Hatshepsut often spoke possessively of “my rekhyt” and asked for the approval of the rekhyt. On one of he obelisks at Karnak she confided, “Now my heart turns this way and that, as I think what the people will say. Those who see my monuments in years to come, and who shall speak of what I have done.”

Queen Hatshepsut as the Woman-King

Hatshepsut got around the issue of her gender and the implication that it made her unfit to rule by calling herself not the King’s Wife but rather the Wife of the god Amun (based on the premise that the king and Amun were one). During her rule Hatshepsut took the name Maatkare, sometimes translated as “Truth is the Soul of the Sun God” — with “maat” meaning “Truth,” “ka” meaning “Soul” and “Re” being the “the Sun God” — an ancient Egyptians expression for order and justice which she seemed to have adopted to legitimize her position. She declared that the god Amun not only had chosen her to be the next pharaoh but also impregnated her mother to produce her divine birth. She thanked Amun by raising obelisks devoted to him at Karnak that were covered with electum, a mixture of gold and silver.

Hatshepsut got around the issue of her gender and the implication that it made her unfit to rule by calling herself not the King’s Wife but rather the Wife of the god Amun (based on the premise that the king and Amun were one). During her rule Hatshepsut took the name Maatkare, sometimes translated as “Truth is the Soul of the Sun God” — with “maat” meaning “Truth,” “ka” meaning “Soul” and “Re” being the “the Sun God” — an ancient Egyptians expression for order and justice which she seemed to have adopted to legitimize her position. She declared that the god Amun not only had chosen her to be the next pharaoh but also impregnated her mother to produce her divine birth. She thanked Amun by raising obelisks devoted to him at Karnak that were covered with electum, a mixture of gold and silver.

Early images of Hatshepsut were clearly feminine with a few kingly touches .She wore an ankle-length skirt like that worn by women and had a feminine face and bust but struck the pose of a king and wore the king’s cobra headdress. As time went on she became more masculine, wearing a pharaoh’s “shendyt” kilt and a false beard, and displaying a broad, open, manly chest, without any feminine touches. The text that accompanied her images were lists of accomplishments like those found with traditional male pharaohs and featured statements like: “My command stands firm like the mountains.” Even so, in most texts she was referred to as a woman, using feminine wordings that sometimes produced things like, “His Majesty, Herself.”

For a long time Hatshepsut was caste by historians as the evil stepmother to Thutmose III, with historian William Hayes, the curator of Egyptian art a the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in the 1950s, calling her a “vain, ambitious and unscrupulous woman” and the “vilest type of usurper.” This view of Hatshepsut is based primarily on Thutmose III’s ruthless campaign to deface Hatshepsut’s monuments and destroy all evidence of her rule after her death. These days many historians say Thutmose III likely carried out the defacements to boost his image, arguing that because most of the defacing was done late in his career it was not done out of malice, suggesting that if he had done it out of spite he would have done it earlier on.

Catharine Roehrig, the curator of Egyptian art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, told National Geographic, “nobody can know what she was like, She ruled for 20 years because she was capable of making things work. I believe she was very canny and that she knew how play one person off against the next — without murdering them or getting murdered herself.”

Hatshepsut’s Official Image

Hatshepsut statue in her Mortuary Temple Dimitri, Laboury of the University of Liège in Belgium wrote: “Hatshepsut. The evolution of Hatshepsut’s official image is probably the best illustration of how ancient Egyptian portraiture could deviate from the model’s actual appearance. As Tefnin has demonstrated, it occurred in three phases. When the regent queen Hatshepsut assumed full kingship, she was depicted with royal titulary as well as traditional regalia, but still as a woman with female dress and anatomy. Her face was a feminine version of the official physiognomy of her three direct predecessors, which was itself inspired by the iconography of Senusret I, who had reigned five centuries earlier. Shortly into her reign, this genealogical mask started to change into a previously unattested and very personalized triangular face, with more elongated feline eyes under curved eyebrows, a small mouth, which was narrow at the corners, and an ostensibly hooked nose. At the same time, the queen emphasized her royal insignia, wearing a broader nemes- headgear and exchanging her female dress for the shendyt-loincloth of male pharaohs, while her anatomy was only allusively feminine, with orange-painted skin—a tone halfway between the yellow of women and the red of men. [Source: Dimitri, Laboury, University of Liège, Belgium, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“As Tefnin stressed, this second stage in the evolution of Hatshepsut’s iconography clearly expresses the queen’s desire to assert her own personality as a king. Nevertheless, the metamorphosis resumed rather quickly and ended in a definitely male royal image, for which Hatshepsut completely waived her femininity. Even if a few epithets or pronouns relating to the queen sporadically remained feminine in the inscriptions from her reign, her images are absolutely masculine from that phase on. They exhibit an explicitly virile musculature, red skin, and a physiognomy that appears as a synthesis of her two first official faces, i.e., a compromise between her very individualized previous portrait, plausibly inspired by her own facial appearance, and the iconography common to her three male predecessors, including young king Thutmose III with whom she decided to share the throne.

“This evolution, indubitably motivated by Hatshepsut’s will and need for legitimation, is of course a very extreme case, due to very exceptional political circumstances. However, it demonstrates that even the sexual identity could be remodeled in ancient Egyptian portraiture according to an ideal image, here the one of the traditional legitimate king. Hatshepsut was the only reigning queen in ancient Egypt who felt the need for such iconographic fiction, i.e., to depict herself as a male pharaoh. In regard to the rendering of the physiognomy, the reigning queen offered a very good case if not of a borrowed personality, at least of a partly borrowed identity. As the heir of specific predecessors, she integrated into her own official visage some of their recognized facial Portrait versus Ideal features to emphasize her legitimacy—like a physiognomic signature accentuating her lineage.

“A similar phenomenon seems to have linked royal portraiture and portrayals of the elite or high officials, which often imitated the former closely. Good examples of this kind of allegiance portraits from the time of Hatshepsut are the numerous statues of Senenmut—most of them, if not all, made in royal workshops—which followed the evolution of the queen’s physiognomy, whereas a few two-dimensional sketches provide a much more individualized face of he same person.”

Queen Hatshepsut Temples and Monuments

Hatshepsut launched an extensive building program. She oversaw the repair of damage casued by the invading Hyksos and built magnificent temples from scratch. She renovated her father’s hall in the Temple of Karnak, added a chapel and erecting four great obelisks nearly 100 feet (30m) tall. Her greatest achievement was her mortuary temple at Deir el Bahri, one of the most beautiful temples in Egypt. She called it the ‘Most Sacred of Sacred Places’. [Source :Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Hatshepsut launched an extensive building program. She oversaw the repair of damage casued by the invading Hyksos and built magnificent temples from scratch. She renovated her father’s hall in the Temple of Karnak, added a chapel and erecting four great obelisks nearly 100 feet (30m) tall. Her greatest achievement was her mortuary temple at Deir el Bahri, one of the most beautiful temples in Egypt. She called it the ‘Most Sacred of Sacred Places’. [Source :Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Hatshepsut began her rule by erecting two 30-meter-high, 450-ton obelisks at the great temple in Karnak. Reliefs commemorating the event show 27 ships manned by 850 oarsmen towing the obelisks up the Nile. Hatshepsut reportedly spared no expenses and poured in "as many bushels of gold as sacks of wheat" to get the obelisk completed. One of the Karnak obelisks is the tallest one in the world. Both were originally covered in glistening electrum, a combination of gold and silver.

On Hatshepsut’s monument-building efforts Chip Brown wrote in National Geographic, “She seems to have been more afraid of anonymity than death. She raised and renovated temples and shrines from the Sinai to Nubia. The grandest obelisks she erected at the vast temple of the great god Amum at Karnak were among the most magnificent ever constructed. She commissioned hundreds of statues of herself and left accounts in stone of her lineage, her titles, her history , both real and concocted, even her thoughts and hopes, which at times she confided with uncommon candor.”

Most of her building projects, which included a network of grand processional roadways and sanctuaries, constructed in and around Thebes (present-day Luxor), the center of he Thutmoside dynasty. A lot of great art was created during her reign, some of which — including granite sphinxes with her likeness, fabulous cartouche jewelry, reliefs, sarcophagi, paintings, manuscripts, vessels, and amulets, “were the subject of a 300-piece exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2006.

Hatshepsut's Temple at Deir el Bahri

Hatshepsut's Temple is a mortuary temple built into the side of a cliff near the Valley of the Kings in Luxor) while Hatshepsut was still alive. Named Djeser Djeseru, "the Splendor of Splendors" or “Holy of Holies” and known today as Deir el-Bahri (Arabic for “northern monastery”), it is regarded as one of the great architectural achievements of the ancient world and was designed to be a place for people to gather for special religious rites connected with the cult of Hatshepsut to guarantee that she live on in the afterlife.

Hatshepsut's Temple was built in 1480 B.C., and dedicated to Amum and several other deities. Built into a dramatic lion-colored sandstone cliff on the eastern face of desert mountain, the temple is comprised of three terraces of colonnades, connected by massive ramps, and a small chamber tunneled deep into the rock and reached by a long ramp. The last set colonnades is set into the face of the cliff. Queen Hatshepsut planted botanical gardens at the site and had incense burners on the terraces.

David Rull Ribó wrote in National Geographic History: In the New Kingdom period, Hatshepsut was one of the first pharaohs who built the so-called Temples of Millions of Years on the western bank of the Nile. Five centuries earlier, in Middle Kingdom times, Pharaoh Mentuhotep II had erected the first mortuary temple here. Perhaps inspired by Mentuhotep, Hatshepsut installed her massive complex at the foot of a cliff, a site now known as Deir el Bahri. The sacred location had been consecrated to the goddess Hathor, protector of the dead and an important funerary deity in Thebes. [Source: David Rull Ribó, National Geographic, March 7, 2024]

In these temples, pharaohs would be worshipped after their deaths. Their mummies, meanwhile, rested elsewhere, entombed in private underground chambers in the Valley of the Kings. As well as being used for royal funerals, the Temples of Millions of Years were the focus for other rituals: some related to royalty, others to deities including the Theban god Amun and the sun god Re. Of all the mortuary temples, Hatshepsut’s would become the main cult structure of the Theban complex.

Construction lasted some 15 years and was carried out under the supervision of Senenmut, a high official and favorite of the pharaoh. The imposing building incorporated ramps and courtyards like the nearby Mentuhotep temple, but Senenmut introduced a number of innovations to create a building of unequaled magnificence. The layout of Hatshepsut’s temple was carefully designed. Most obviously, it was positioned to align perfectly with the Temple of Amun at Karnak, on the opposite bank of the Nile. In addition, the precise eastwest alignment of its central causeway mirrored the daily path of the sun, or, according to the beliefs of the day, the path of the god Re.

The temple was also aligned with the Valley of the Kings, which lies to the west. This royal necropolis had been inaugurated by Hatshepsut’s father, Thutmose I. In fact, tomb KV20, the burial place of Hatshepsut and Thutmose I, lies in a straight line from the sanctuary of Amun, the innermost chamber of Hatshepsut’s temple. Some experts have suggested that the original plan was to connect KV20 with the sanctuary of Amun via a tunnel through the interposing cliff, but the poor quality of the rock prevented it.

Features and Reliefs at Hatshepsut's Temple at Deir el Bahri

Hatshepsut’s temple is huge, roughly the length of 2½ football fields, but the overall effect of the architecture is surprisingly light, especially in comparison to heavy fortress-like temples erected by her predecessors. A ramp sided by pillars leads from a large first courtyard to a second courtyard. At the back of this is a colonnade with walls and small enclosures with engravings and reliefs showing episodes from the queen’s life and images of gods. The lower levels featured pools and gardens planted with fragrant trees. Some 100 statues of Hatshepsut as a sphinx guarded the processional way. The majority of these were smashed by Hatshepsut’s successor and stepson Thutmose III and thrown in a pit in front of the temple.

The rear wall of the second courtyard consist of the Birth Colonnade on one side of the ramp and the Punt Colonnade on the other. The Birth Colonnade is a small sheltered area at the top of the terrace that describes the preparation for and birth of Queen Hatshepsut. Particularly interesting is the scene of birds being captured in nets. The Punt Colonnade depicts a trading expedition to Punt, with boats piled high with luxuries such as gold, ebony, ivory and exotic animals.

David Rull Ribó wrote in National Geographic History: Most New Kingdom commemorative temples featured chambers separated by monumental gateways (pylons), like those that can still be seen at Luxor and Karnak. Hatshepsut’s temple, on the other hand, was arranged around a central ramp or causeway. Spread along this causeway at different heights were three large courtyards. Today, the walls and courtyards of Hatshepsut’s temple might look somewhat plain. In her time they would have been filled with vibrant color, surrounded by lush gardens and pools and richly decorated with sculpture and reliefs. Each decorative element conveyed a religious or political message, in keeping with the ceremonial use of the building. Stone balustrades flank the central ramp, guarded by imposing stone lions. A colonnade separates the first and second courtyards. To highlight Hatshepsut’s piety and devotion, reliefs depict two massive obelisks on their way to the Temple of Amun at Karnak. [Source: David Rull Ribó, National Geographic, March 7, 2024]

Splendid reliefs were carved on the portico of the second courtyard of the temple at Deir el Bahri. Some depict Hatshepsut’s expedition to the Land of Punt in the eighth and ninth years of her reign. The reliefs provide a glimpse of the terrain, fauna, flora, and inhabitants of this enigmatic land, perhaps located in the Horn of Africa or in the south of the Arabian Peninsula. Other reliefs represent the divine birth of Hatshepsut, who, according to tradition, had been begotten by the god Amun-Re during a visit he made to Ahmose, the wife of Thutmose I. Her divine origin was an important tool in legitimizing Hatshepsut’s rule over Egypt. In the second courtyard there are also two sanctuaries: one dedicated to Hathor and the other to Anubis, a funerary god. [Source: David Rull Ribó, National Geographic, March 7, 2024]

Twenty-four colossal Osirides — statues of Pharaoh Hatshepsut as Osiris, god of the after-life — flanked the entrance to the third courtyard. She wears the false beard (postiche) and the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt (pschent), and she holds the symbols of royalty. This uppermost courtyard had sanctuaries dedicated to the royal cult, to the solar god Re-Horakhty, and to Anubis.

Festivals and Events at Hatshepsut's Temple

David Rull Ribó wrote in National Geographic History: In the central part of this last courtyard stood the temple’s innermost chambers, a sanctuary dedicated to Amun-Re. Inside were three adjoining chambers decorated with scenes of Hatshepsut and the god Amun. [Source: David Rull Ribó, National Geographic, March 7, 2024]

During her funeral Queen Hatshepsut was carried up the ramps to a funerary chamber inside the temple. In the 7th century the Copts used the temple as a monastery.

The sanctuary of Amun-Re was the main setting for a ceremony that was celebrated every year in Thebes: the Beautiful Festival of the Valley. The celebration dates back to the Middle Kingdom and reached new heights in Hatshepsut’s time. Badly deteriorated reliefs that run along the upper courtyard of Hatshepsut’s temple depict the festivities. During the second month of the harvest season (shemu) in early summer, the pharaoh would lead a procession bearing the image of Amun followed by a retinue of nobles, priests, dancers, and soldiers. They would begin at Karnak Temple, cross the Nile, and visit the mortuary temples.

Hatsheput’s Expedition to Punt

Around the second courtyard of Hatshepsut's Temple at Deir el Bahri are famous reliefs showing a trading expedition that Hatshepsut sent to the Land of Punt, believed to be located on the Horn of Africa in of present-day Somalia-Eritrea. Myrrh trees were brought back from the expedition and planted in the temple complex. Their resin was later used in temple rituals. [Source: David Rull Ribó, National Geographic, March 7, 2024]

David Rull Ribó wrote in National Geographic History: The expedition reached Punt by sailing along the shores of the Red Sea. The Egyptians loaded their ships with a cargo of ivory, cinnamon, incense, cosmetics, and animal skins. The relief on the portico highlights the myrrh trees and also depicts Hatshepsut presenting the cargo from Punt to the god Amun as an offering. [Source: David Rull Ribó, National Geographic, March 7, 2024]

Fragments of the relief are in the Cairo Museum. According to the museum; The expedition was sent in order to obtain exotic goods for Hatsheput’s treasury and her pleasure – exotic animals, gold, ebony. One of the relief depicts king Parehu and queen Ati. The king is very slender and wears a kilt with a long sash, two under-tassels and a dagger tucked into the waistband. His long, slender beard distinguishes him as a foreigner. The queen is excessively overweight with extreme curvature of the spine, rolls of fat on arms, body and legs. She wears a sleeveless dress, belted at the waist, a necklace with large disk beads, bracelets and anklets. On the right edge is a partial depiction of two rows of gold rings in baskets and a third of undetermined identification.

See Separate Article: PUNT AND THE INCENSE COUNTRIES africame.factsanddetails.com

Karnak Temple Under Queen Hatshepsut

Elaine Sullivan of UCLA wrote: “The wadjet hall would be dramatically changed during the reign of Hatshepsut. The queen removed her father’s numerous stone columns and replaced them with five gilded- wood papyriform wadj-columns (wadj being the Egyptian term for papyrus). In the center of the hall she erected two red granite obelisks (one remains standing today) with electrum overlay. These tall monuments prevented her from roofing the hall completely, but she covered the side aisles of the hall with a wooden ceiling. The queen’s obelisks were dedicated to the celebration of her Sed Festival in the 16th year of her reign. [Source: Elaine Sullivan, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Hatshepsut transformed the very core of Karnak, removing the Osiride portico of the Middle Kingdom temple and most of the forecourt constructions of Amenhotep I, including his entrance gate and bark chapels. To the front of Senusret’s temple, she appended a suite of rooms, her “Palace of Maat”. The queen ordered a beautiful two-roomed bark chapel of rose quartzite and black diorite, the Red Chapel, as a showpiece for Amun-Ra. In their recent republication of the chapel, CFEETK scholars concluded that the chapel’s placement was, as traditionally thought, within the Palace of Maat. As the insertion of the chapel into the Palace of Maat would only have been possible if renovations to the palace’s original rooms (including the removal of a number of the walls on the northern side) took place during the reign of the queen, it seems that Hatshepsut re-envisioned these rooms expressly to expand the area for her Red Chapel, finished only sometime around year 17 of her reign.

“Over 200 limestone blocks recovered primarily from the “cachette court” have been identified by Gabolde as part of a multiple- roomed structure (named the Netjery-Menu) dated to the early co-regency of the queen. Relief scenes and inscriptions depict Thutmose II, Hatshepsut, her daughter Neferura, and Thutmose III involved in the temple’s daily ritual. ....Another recently rediscovered monument of the queen’s was composed of a number of limestone niches dedicated to the royal statuary cult. These niches, also dated to the early years of the queen’s co-regency, were seemingly removed before she ascended to the throne as king.

“Hatshepsut placed another pair of obelisks at the eastern edge of Karnak, outside the stone enclosure walls of Thutmose I. Although now destroyed, the obelisks are mentioned in a quarry inscription at Aswan and depicted in the queen’s temple at Deir el Bahri. Luc Gabolde and scholars from the CFEETK have been working on documenting pieces from these obelisks, and they have reconstructed their appearance as displaying a central line of hieroglyphs, flanked by scenes of Hatshepsut (and sometimes her nephew) with the god Amun-Ra. “A large stone pylon, the eighth, was constructed by the queen to the south of the temple, along what appears to have been the established north-south processional route...Reused blocks from the queen’s temple of Mut have recently been discovered during excavations at that site, and the Thutmoside temple and an accompanying triple bark-shrine at Luxor are known to have played a role in the queen’s Opet Festival ceremonies.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024