Home | Category: Old and Middle Kingdom (Age of the Pyramids)

BUILDING MATERIALS FOR THE PYRAMIDS

cutting the blocks

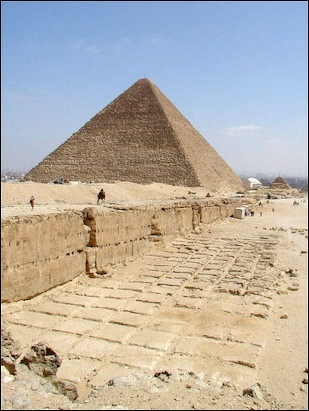

The foundations of the pyramids were laid with limestone blocks. Building stones were predominantly limestone and granite, while mudbrick was used earlier for mastabas. Mudbrick was also used to build later Middle Kingdom Pyramids. A brilliant white limestone provided the final outer layer for the Giza pyramids, creating shimmering perhaps blinding surface cover in the direct Egyptian sun. Limestone was used for all but the lowest course of outer casing on Khafre and the lower 16 courses of Menkaure. These lower casings were made of granite. Some of the stones were quarried from bedrock near the pyramids. The fine white Tura limestone was used from the outer layers of the pyramids came from quarries on the other side of the Nile. Granite used as a build material came from the Aswan area. [Source: PBS]

Jimmy Dunn wrote in touregypt.net: “Many of the pyramids were built with a number of different stone materials. Most of the material used was fairly rough, low grade limestone used to build the pyramid core, while fine white limestone was often employed for the outer casing as well as to cover interior walls, though pink granite was also often used on inner walls. Basalt or alabaster was not uncommon for floors, particularly in the mortuary temples and as was mudbricks to build walls within the temples (though often as not they had limestone walls). [Source: Jimmy Dunn, touregypt.net/construction =]

“Egypt is a country rich in stone and was sometimes even referred to as the "state of stone". In particular, Egypt has a great quantity of limestone formation, which the Egyptians called "white stone", because during the Cretaceous period Egypt was covered with seawater. The country is also rich in sandstone, but it was never really used much until the New Kingdom. Limestone seems to have first been employed in the area of Saqqara, where it is of poor quality but layered in regular, strong formations as much as half a meter thick. This limestone is coarse grained with yellow to greenish gray shading. The layers are separated from each other by thin layers of clay and the coloration may vary according to layer. It could often be quarried very near the building sites, and quarries have been found at Saqqara, Giza, Dahshur and other locations.” =

“Pink granite, basalt and alabaster were used much more sparingly. Most of this material was moved from various locations in southern Egypt by barges on the Nile. Pink granite probably most often came from the quarries around Aswan. Basalt, on the other hand was not as far away. Only recently have we discovered that most of the basalt used in pyramid construction came from an Oligocene flow located at the northern edge of the Fayoum Depression (Oasis). Here, we find the worlds oldest paved road, which led to the shores of what once was a lake. During the Nile inundation each year, this lake made a connection to the Nile, so at that time, the basalt was moved across the lake and into the Nile for transport. =

“Mudbricks, of course were made throughout Egypt and were a common building material everywhere, in common homes and palaces and probably many city buildings. The better mudbricks were fired, or "burnt" in an oven, though it was not uncommon for mudbick not to be fired, and so not as durable. Unfortunately, most structures built of mudbrick have not weathered the ravages of time well. They were built using wooden forms and Nile mud mixed with various fillers. =

“In the mid 1980s a French/Egyptian team investigated the Great Pyramid using ultrasound technology. Their efforts revealed that large cavities within the structure had been filled with pure sand. This is referred to as the "chamber method", and could have considerably increased the pace of work. In addition, we also know that the Great Pyramid utilized a rock outcropping as part of its core.” =

RELATED ARTICLES:

AGE OF THE PYRAMIDS AND THE PHARAOHS THAT BUILT THEM africame.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY PYRAMIDS OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PYRAMIDS OF GIZA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PYRAMIDS OF ANCIENT EGYPT: HISTORY, COMPONENTS AND TYPES

africame.factsanddetails.com

BUILDING THE PYRAMIDS: LAYOUT, ENGINEERING, ALIGNMENT africame.factsanddetails.com

PYRAMID RAMPS AND PUTTING THE STONES IN PLACE africame.factsanddetails.com

STUDY OF THE PYRAMIDS: PYRAMIDOLOGY, SERIOUS SCHOLARSHIP AND PSEUDOSCIENCE africame.factsanddetails.com

PYRAMID BUILDERS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LIFE OF THE PYRAMID BUILDERS africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Complete Pyramids” by Mark Lehner (1997) Amazon.com;

“Giza and the Pyramids: The Definitive History” by Mark Lehner and Zahi Hawass (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Egyptian Pyramids: A Comprehensive, Illustrated Reference” by J.P. Lepre (1990, 2006) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Pyramids and Mastaba Tombs” by Philip J. Watson (2009) Amazon.com;

“How the Great Pyramid Was Built” by Craig B. Smith (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Secret of the Great Pyramid: How One Man's Obsession Led to the Solution of Ancient Egypt's Greatest Mystery”, Illustrated, by Bob Brier, Jean-Pierre Houdin (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Great Pyramid: 2590 BC Onwards - an Insight into the Construction, Meaning and Exploration of the Great Pyramid of Giza” By Franck Monnier, Dr. David Lightbody (2019) Amazon.com;

“ Pyramid (DK Eyewitness Books) by James Putnam (2011) Amazon.com;

”The Pyramid Builder: Cheops, the Man behind the Great Pyramid” by Christine El Mahdy (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt” by A. David (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Builders of the Pyramids” by Zahi Hawass (2009) Amazon.com;

“Mountains of the Pharaohs: The Untold Story of the Pyramid Builders” by Zahi Hawass (2024) Amazon.com;

Building Stones in Ancient Egypt

unfinished stones for Menkaure's pyramid

James Harrell of the University of Toledo wrote: “The building stones of ancient Egypt are those relatively soft, plentiful rocks used to construct most temples, pyramids, and mastaba tombs. They were also employed for the interior passages, burialchambers, and outer casings of mud-brick pyramids and mastabas. Similarly, building stones were used in other mud-brick structures of ancient Egypt wherever extra strength was needed, such as bases for wood pillars, and lintels, thresholds, and jambs for doors. Limestone and sandstone were the principal building stones employed by the Egyptians, while anhydrite and gypsum were also used along the Red Sea coast. A total of 128 ancient quarries for building stones are known (89 for limestone, 36 for sandstone, and three for gypsum), but there are probably many others still undiscovered or destroyed by modern quarrying. [Source: James Harrell, University of Toledo, OH, Environmental Sciences, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“The building stones of ancient Egypt are those relatively soft, plentiful rocks used to construct most Dynastic temples, pyramids, and mastaba tombs. For the pyramids and mastabas made largely of sun-dried mud- brick, building stones were still employed for the interior passages, burial chambers, and outer casings. Similarly, building stones were used in other mud-brick structures of ancient Egypt (e.g., royal palaces, fortresses, storehouses, workshops, and common dwellings) wherever extra strength was needed, such as bases for wood pillars, and lintels, thresholds, and jambs for doors, but also occasionally for columns. Ptolemaic and Roman cities along the Mediterranean coast, Alexandria chief among them, followed the building norms of the rest of the Greco- Roman world, and so used stone not only for temples but also for palaces, villas, civic buildings, and other structures. Limestone and sandstone were the principal building stones used by the Egyptians. These are sedimentary rocks, the limestone consisting largely of calcite (CaCO3) and the sandstone composed of sand grains of mostly quartz (SiO2) but also feldspar and other minerals. The Egyptian names for limestone were jnr HD nfr n ajn and jnr HD nfr n r-Aw, both translating as “fine white stone of Tura-Masara” (ajn and r-Aw referring, respectively, to the cave-like quarry openings and the nearby geothermal springs at Helwan). Sandstone was called jnr HD nfr n rwDt, or occasionally jnr HD mnx n rwDt, both meaning “fine, or excellent, light-colored hard stone.” Although usually translated as “white,” here HD probably has a more general meaning of “light colored.” Sandstone is not normally considered a hard rock (rwDt), but it is often harder than limestone. In the above names, the nfr (fine) or HD or even both were sometimes omitted, and in the term for sandstone the n was later dropped.

“From Early Dynastic times onward, limestone was the construction material of choice for temples, pyramids, and mastabas wherever limestone bedrock occurred—that is, along the Mediterranean coast and in the Nile Valley from Cairo in the north to Esna in the south. Where sandstone bedrock was present in the Nile Valley, from Esna south into Sudan, this was the only building stone employed, but sandstone was also commonly imported into the southern portion of the limestone region from the Middle Kingdom onward. The first large-scale use of sandstone occurred in the Edfu region where it was employed for interior pavement and wall veneer in Early Dynastic tombs at Hierakonpolis and for a small 3rd Dynasty pyramid at Naga el- Goneima, about 5 kilometers southwest of the Edfu temple. Apart from this pyramid, the earliest use of sandstone in monumental architecture was for some Middle Kingdom temples in the Theban region (e.g., the Mentuhotep I mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri and the Senusret I shrine at Karnak). From the beginning of the New Kingdom onward, with the notable exception of Queen Hatshepsut’s limestone mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, most Theban temples were built either largely or entirely of sandstone. Further into the limestone region, sandstone was also used for the Ptolemaic and Roman Hathor temple at Dendara, portions of the Sety I and Ramesses II temples at Abydos, and the 18th Dynasty Aten temple at el-Amarna. The preference for sandstone over limestone as a building material coincided with the transfer of religious and political authority from Memphis in Lower Egypt to Thebes in the 18th Dynasty. The Egyptians also recognized at this time that sandstone was superior to limestone in terms of the strength and size of blocks obtainable, and this permitted the construction of larger temples with longer architraves.

“The Serabit el-Khadim temple in the Sinai is of sandstone, and temples in the Western Desert oases were built of either limestone (Fayum and Siwa) or sandstone (Bahriya, Fayum, Kharga, and Dakhla), depending on the local bedrock. In the Eastern Desert, limestone was used for the facing on the Old Kingdom flood-control dam in Wadi Garawi near Helwan (the “Sadd el-Kafara”; Fahlbusch 2004), and sandstone was the building material for numerous Ptolemaic and Roman road stations. Both types of bedrock in the Nile Valley and western oases hosted rock-cut shrines and especially tombs, and these are the sources of many of the relief scenes now in museum and private collections. Limestone and sandstone were additionally employed for statuary and other non-architectural applications when harder and more attractive ornamental stones were either unaffordable or unavailable. In such cases, the otherwise drab- looking building stones were usually painted in bright colors. Conversely, structures built of limestone and sandstone often included some ornamental stones, most notably granite and granodiorite from Aswan, as well as silicified sandstone, but also basalt and travertine in the Old Kingdom.”

Concrete Rather Than Limestone Used to Make the Pyramids?

How is it possible that some of the blocks of stone used to make the pyramids are so perfectly matched that not even a human hair can be inserted between them? Why, despite the existence of millions of tons of stone, carved presumably with copper chisels, has not one copper chisel ever been found on the Giza Plateau? Cement may be the answer to these questions. [Source: Sheila Berninger and Dorilona Rose, Live Science, May 18, 2007]

Some scientists believe that the limestone blocks are not limestone blocks at all but rather concrete blocks that were formed in place. French scientist who first proposed this theory said Egyptian authorities prevented them from taking the samples to prove their theory. The theory is partly based on the narrowness of the joints between the rocks, which the scientists say is easy to create if the rock is formed but nearly impossible with quarried stones unless milling tools are available. If the theory is true it would end the need to explain how the massive stones were moved. Many think the theory is nonsense.

Research revealed in December 2006 by a team lead by Michel Barsoum, a professor of material engineering at Drexel University, indicate that some of the structures used to make the pyramids were concrete blocks, demonstrating that the Egyptians had developed the technology to make concrete and were using in construction. The determination was made by analyzing the composition of the minerals in several parts of the Khufu pyramid and finding mineral traces not normally found in limestone blocks but that are present in sand, clay and lime used to make concrete. Most archeologists still believe the pyramids are made of cut limestone blocks. Romans are usually given credit for inventing concrete around 100 B.C.

Barsoums has reasoned that using concrete made it possible to build massive structures like the pyramids. He suggested the Egyptians used concrete blocks in the inner and outer casing of the pyramids as well as probably on the top levels too, and doing so was much easier than hoisting massive carved stones. Many scientists question the finding, saying that the samples could have been taken where the pyramid was restored in modern times with concrete.

Sheila Berninger and Dorilona Rose wrote in Live Science: Barsoum’s team “found that the tiniest structures within the inner and outer casing stones were indeed consistent with a reconstituted limestone. The cement binding the limestone aggregate was either silicon dioxide (the building block of quartz) or a calcium and magnesium-rich silicate mineral. The stones also had a high water content — unusual for the normally dry, natural limestone found on the Giza plateau — and the cementing phases, in both the inner and outer casing stones, were amorphous, in other words, their atoms were not arranged in a regular and periodic array. Sedimentary rocks such as limestone are seldom, if ever, amorphous. The sample chemistries the researchers found do not exist anywhere in nature. "Therefore," Barsoum said, "it's very improbable that the outer and inner casing stones that we examined were chiseled from a natural limestone block." More startlingly, Barsoum...discovered the presence of silicon dioxide nanoscale spheres (with diameters only billionths of a meter across) in one of the samples. This discovery further confirms that these blocks are not natural limestone.” [Source: Sheila Berninger and Dorilona Rose, Live Science, May 18, 2007]

Great Pyramid Cores

the core is mainly what remains of the Black Pyramid

The cores of the larger pyramids were made of crudely cut limestone blocks, with the seams between filled with pieces of limestone and blobs of gypsum mortar. Smaller pyramids had cores with small stones, mud or mud brick retaining walls. In some places sand and rubble was sued as fill. John Watson, wrote in touregypt.net: “Most of Egypt's pyramids are made up of core stones that fill the bulk of the pyramid. These core stones resulted in tiers, making most pyramids at least internally we believe, step pyramids, though the steps may have been very crude. Then there was masonry that filled in the steps, which we could call packing stones. There was also a softer stone that the builders set between the core and casing that is frequently referred to as packing stone, and finally the pyramid was finished off with a smooth outer casing of limestone or granite. [Source: John Watson, touregypt.net/construction =]

“Many books that Khufu's Pyramid, greatest of all in Egypt, contains an estimated 2.3 million blocks of stone weighing on average about 2.5 tons. In the past, both professional and amateur theorists assume that the pyramids are composed of generic blocks of this weight. Next, they set about solving the problem of how the builders could have possibly raised and set so many huge blocks....Traditional assumptions are really valid. In fact, recent analysis has suggested that Khufu's Pyramid has far fewer large blocks than originally supposed, and those who maintain that the blocks are more or less uniformly 2.5 tons are simply wrong. = “At first glance, the sides of the Giza Pyramids, stripped of most of their smooth outer casing during the Middle Ages, look like regular steps. These are actually the courses of backing stones, so called because they once filled in the space between the pyramid core and outer casing. However, a closer examination reveals that the steps are not at all regular. In fact, rather than regular, modular, squared blocks of stone neatly stocked, there is considerable "slop factor", even in the Great Pyramid of Khufu. =

“Not only are the backing stones irregular, they are also progressively smaller toward the top. Behind the backing stones, the core stones are actually even more irregular. We know this because, in the 1830s, Howard Vyse blasted a hole in the center of the south side of Khufu's's Pyramid while looking for another entrance. This wound in the pyramid can still be seen today, and in it, we can see how the builders dumped great globs of mortar and stone rubble in wide spaces between the stones. Here, there are big blocks, small chunks of rock, wedge shaped pieces, oval and trapezoidal pieces, as well as smaller stone fragments jammed into spaces as wide as 22 centimeters between larger blocks. =

“In the Pyramid of Khafre, Giza's second largest structure, event the coursing of the base core stones is not uniform. The builders tailored blocks to fit the sloping bedrock that they left protruding in the core as they leveled the surrounding court and terrace. In fact, in this pyramid's northeast and southeast corners, where the downward slope of the plateau left no bedrock in the core, the builders used enormous limestone blocks, two courses thick, to level the perimeter. Higher up, the core is made up of very rough, irregular stones. The upper third of the pyramid core appears to be stone blocks in regular stepped courses, but on closer inspection, the heights of these steps range from ninety centimeters to 1.20 meters, and the widths of the steps vary from 23 centimeters to a meter. =

“Although considerable irregularity shows in the inner core of even the largest and finest pyramids at Giza, the builders did not simply pile up rubble as, in all probability, they built the core slightly ahead of the casing. There is evidence that they built up these pyramids in large chunks of structure. The first pyramids of Egypt were step pyramids, which are not true pyramids, lacking the smooth outer casing. Many pyramid theorists assume that a stepped core makes up the bulk of every pyramid. Indeed, the pyramid at Meidum does have such a core, made up with fine sharp corners and faces. In fact, the first true pyramids were indeed conversions of step pyramids. However, we actually do not know whether the largest pyramids of the 4th Dynasty, those usually best known to the world, are built with an inner step pyramid. =

“Irregardless of the irregularity of their cores, the Giza Pyramids do have the most massive, large block masonry of all Egyptian pyramids. These classic pyramids of popular imagination were built in only three generations and yet, all of the other pyramids of kings (excluding queens and other satellite pyramids) contain only 54 percent of the total mass of the pyramids of Sneferu, his son Khufu, and grandson Khafre. Many of the characteristics of these pyramids are very precise, but while they are not as perfect as many might imagine, they nevertheless represent true landmarks in human achievement.” =

Quarrying Stones for the Pyramids

Some of the stones were quarried from bedrock near the pyramids. The fine white Tura limestone was used from the outer layers of the pyramids came from quarries on the other side of the Nile. Granite used as a build material came from the Aswan area.

Quarries Tourah (1878)

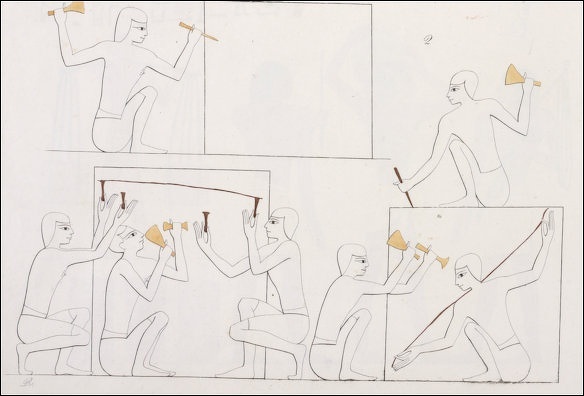

Jimmy Dunn wrote in touregypt.net: In order to quarry the limestone in sites not far from where the pyramids were built “the blocks were marked out with just enough space in between each to allow for a small passageway for the workers to cut the blocks. The workmen would use a number of different tools to cut the blocks, including copper pickaxes and chisels, granite hammers, dolerite and other hard stone tools. =

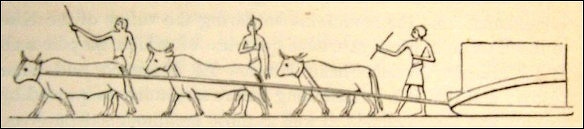

“The finer, white limestone employed in the pyramids and mortuary temples was not as easy to quarry, and had to be found further from the building site. One of the man sources for this limestone was the Muqattam hills on the west bank of the Nile near modern Tura and Maasara. This stone laid buried further from the surface, so tunnels had to be dug in order to reach the actual stone quarry. Sometimes these deposits were as deep as fifty meters, and huge caverns had to be built to reach the quarry. Generally, large chunks of stone were removed, and then finely cut into blocks. The blocks were then moved to the building site on large wooden sledges pulled by oxen. The path they took would be prepared with a mud layer from the Nile in order to facilitate the moving. =

“Alabaster is quarried from either open pits or underground. In open pits, veins of Alabaster are found 12 to 20 feet below the surface under a layer of shale which can be two or three feet deep. The rocks have an average height of 16-20 inches and a diameter of two to three feet. Much of the alabaster used in the pyramids probably came from Hatnub, a large quarry near Amarna north of modern Luxor. However, it should be pointed out that by even the end of the Old Kingdom, there were hundreds of various types of quarries scattered across the western and eastern deserts, the Sinai and southern Palestine.” [Source: Jimmy Dunn, touregypt.net/construction =]

Dr Ian Shaw of the University of Liverpool wrote for the BBC: “The King's Chamber was made entirely from blocks of Aswan granite. Since the Second Dynasty, granite had frequently been used in the construction of royal tombs. The burial chambers and corridors of many pyramids from the Third to the Twelfth Dynasty were lined with pink granite, and some pyramids were also given granite external casing (eg those of Khafra and Menkaura, at Giza) or granite pyramidia (cap-stones). [Source: Dr Ian Shaw, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“The Aswan quarries are the only Egyptian hard-stone workings that have been studied in detail. It has been estimated, on the basis of surviving monuments, that around 45,000 cubic metres of stone were removed from the Aswan quarries during the Old Kingdom (Third to Sixth Dynasties). It seems likely that loose surface boulders would have been exploited first.” |::|

Shaping the Pyramid Stones

The limestone and granite blocks used to make the great pyramids weighed between one and 40 tons, averaging 2.5 tons. Soft copper tools and stone hammers were used to chisel grooves in the stones; copper blades moved back and forth with abrasive sand cuts the stone; and wetted wooden wedges were used to pry slabs from the cliff faces. After being pried loose in their quarries the stones were shaped with copper chisels and stone pickaxes to the necessary size so that excess weight did not have to be transported.

Dr Ian Shaw of the University of Liverpool wrote for the BBC: ““It is unclear what kinds of tools were used for quarrying during the time of the pharaohs. The tool marks preserved on many soft-stone quarry walls (eg the sandstone quarries at Gebel el-Silsila) suggest that some form of pointed copper alloy pick, axe or maul was used during the Old and Middle Kingdoms, followed by the use of a mallet-driven pointed chisel from the Eighteenth Dynasty onwards. This technique would, however, have been unsuitable for the extraction of harder stones such as granite. As mentioned above, Old Kingdom quarriers were probably simply prising large boulders of granite out of the sand. [Source: Dr Ian Shaw, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“There has been much debate concerning the techniques used by ancient Egyptians to cut and dress rough-quarried granite boulders or blocks for use in masonry. No remnants of the actual drilling equipment or saws have survived, leaving Egyptologists to make guesses about drilling and sawing techniques on the basis of tomb-scenes, or the many marks left on surviving granite items such as statues. |::|

“In recent years, however, a long series of archaeological experiments has been undertaken by the British Egyptologist Denys Stocks. Like many previous researchers, Stocks recognised that the copper alloy drills or saws would have worn away rapidly if used to cut through granite without assistance. He therefore experimented with the addition of quartz sand, poured in between the cutting edge of a drill and the granite, so the sharp crystals could give the drill the necessary 'bite' into the rock, and found that this method could work. It seems a practical solution, as no special teeth would have been needed for the masons' tools, only a good supply of desert sand-and this theory is gaining acceptance in academic circles.” |::|

Moving the Pyramid Stones on Water and Land

Some of the stones were quarried from bedrock near the pyramids. The fine white Tura limestone was used from the outer layers of the pyramids came from quarries on the other side of the Nile. Granite used as a build material came from the Aswan area.

According to PBS: “The Nile was used to transport supplies and building materials to the pyramids. During the annual flooding of the Nile, a natural harbor was created by the high waters that came conveniently close to the plateau. These harbors may have stayed water-filled year round. Some of the limestone came from Tura, across the river, granite from Aswan, copper from Sinai, and cedar for the boats from Lebanon.”

from Secrets of the Pyramids secretofthepyramids.com

No animals or machines were used to transport the blocks. Whenever possible the stones were transported on the Nile. Canals may have been used to get the stones as close to the site as possible. On the banks of the Nile, teams of perhaps 20 to 50 men hauled the stones on wooden sledges to the building sites where master carvers shaped each block and levered it into place. A hoisting machine was used to lift stones ("none of them were thirty feet in length") into place.

Lehner told PBS: “During the making of the NOVA film "This Old Pyramid," Egyptian workers successfully pulled a large limestone block along using wooden rollers.” In the “NOVA experiment we found that 12 men could pull a one-and-a-half-ton block over a slick surface with great ease. And then you could come up with very conservative estimates as to the number of men it would take to pull an average-sized block the distance from the quarry, which we know, to the Pyramid. And you could even factor in different configurations of the ramp, which would give you a different length....How many men were required to deliver 340 stones a day, which is what you would have to deliver to the Khufu Pyramid to build it in 20 years.... Thirty-four stones can get delivered by x number of gangs of 20 men, and it comes out to something like 2,000, somewhere in that area. So now we've got 1,200 men in the quarry, which is a very generous estimate, 2,000 men delivering. So that's 3,200.

Waterways and Maritime Infrastructure of the Giza Plateau

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: The papyri discovered at Wadi el-Jarf offer revealing clues to the layout of the Giza Plateau and its maritime infrastructure during the period of the pyramid’s construction. In the papyri, when Inspector Merer and his men are described approaching the plateau with a boatful of limestone blocks, they pass through the Ro-She Khufu (Mouth of the Lake of Khufu) into either the She Khufu (Lake of Khufu) or the She Akhet Khufu (Lake of the Horizon of Khufu). According to Egyptologist Mark Lehner, director of Ancient Egypt Research Associates, who has led excavations at the Giza Plateau for three decades, this supports scholars’ theory that the ancient Egyptians built a network of artificial basins that allowed heavily laden boats to deposit their cargo at the plateau’s edge, facilitating the delivery of materials necessary to construct the pyramid. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022]

What appears to be the outline of one of these basins — likely the She Akhet Khufu — was detected through test excavations carried out in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The basin’s western edge seems to have been the site of Khufu’s valley temple, which had a massive limestone foundation covered with black basalt slabs. Sections of colossal walls forming the other three sides of the basin, also composed of basalt on limestone foundations, have been located as well. In all, the basin measured around a quarter of a mile by a third of a mile. Based on cores taken from its center, Lehner believes the basin was dredged to a depth of between 26 and 33 feet, allowing ample clearance for boats such as that captained by Inspector Merer. “The correspondence between archaeology and the texts from Wadi el-Jarf is phenomenal,” says Lehner.

Also MERER'S DIARY: 4,600-YEAR-OLD LOGBOOK ABOUT PYRAMID WORKERS africame.factsanddetails.com

Waterway Used in the Construction of the Giza Pyramids Found

A lost branch of the River Nile was used by ancient Egyptians to transport the enormous stones of the Great Pyramid at Giza, a study published by Nature in in the journal Communications Earth & Environment in May 2024 suggests. Joe Pinkstone wrote in The Telegraph: Scientists have now discovered a 40-mile long branch of the River Nile which existed during the time of pharoahs but has subsequently been buried beneath farmland and desert. The former Nile branch was found using satellite imagery, geophysical surveys and rock samples. Analysis revealed it ran along the foothills of the Western Desert Plateau, close to the pyramid fields. The scientists, led by the University of North Carolina Wilmington, named the arm of the river the “Ahramat Nile Branch”. Ahramat means “pyramids” in Arabic. [Source: Joe Pinkstone, The Telegraph, May 17, 2024]

“We suggest that the Ahramat Branch played a role in the monuments’ construction and that it was simultaneously active and used as a transportation waterway for workmen and building materials to the pyramids’ sites,” the scientists write in their paper. The authors add that many of the pyramids have causeways connected to the extinct branch and it is likely there was a string of harbours along the bank, where building materials were unloaded. Analysis suggests that the Ahramat branch was pivotal to construction and trade in the Old Kingdom, as five temples (the Bent Pyramid, the Pyramid of Khafre, the Pyramid of Menkaure, the Pyramid of Sahure and the Pyramid of Pepi II) were “positioned adjacent to the riverbank of the Ahramat Branch”.

The study suggests the Ahramat branch ran close to the ancient Egyptian capital of Memphis. It is thought it was turned barren by a 30-year-long drought 4,200 years ago, leaving the arid riverbed under three meters of sand. “[This] strongly implies that this river branch was contemporaneously functioning during the Old Kingdom, at the time of pyramid construction,” the team write. Data on water levels and the elevation level on which the pyramids were built show that throughout the Egyptian dynasties, the river was getting progressively lower. The scientists write: “The enormity of this branch and its proximity to the pyramid complexes, in addition to the fact that the pyramids’ causeways terminate at its riverbank, all imply that this branch was active and operational during the construction phase of these pyramids. ”“This waterway would have connected important locations in ancient Egypt, including cities and towns, and therefore, played an important role in the cultural landscape of the region. ”

Pyramid Stones May Have Been Pulled on Wet Sand by a Sledge

The ancient Egyptians may have moved massive stone blocks used to make the Greeks across the desert by wetting the sand in front of a contraption built to pull the heavy objects, according to a new study. Denise Chow of Live Science wrote: “Physicists at the University of Amsterdam investigated the forces needed to pull weighty objects on a giant sled over desert sand, and discovered that dampening the sand in front of the primitive device reduces friction on the sled, making it easier to operate. [Source: Denise Chow, Live Science, May 1, 2014 ^=^]

“To make their discovery, the researchers picked up on clues from the ancient Egyptians themselves. A wall painting discovered in the ancient tomb of Djehutihotep, which dates back to about 1900 B.C., depicts 172 men hauling an immense statue using ropes attached to a sledge. In the drawing, a person can be seen standing on the front of the sledge, pouring water over the sand, said study lead author Daniel Bonn, a physics professor at the University of Amsterdam. "Egyptologists thought it was a purely ceremonial act," Bonn told Live Science. "The question was: Why did they do it?" ^=^

“Bonn and his colleagues constructed miniature sleds and experimented with pulling heavy objects through trays of sand. When the researchers dragged the sleds over dry sand, they noticed clumps would build up in front of the contraptions, requiring more force to pull them across. Adding water to the sand, however, increased its stiffness, and the sleds were able to glide more easily across the surface. This is because droplets of water create bridges between the grains of sand, which helps them stick together, the scientists said. It is also the same reason why using wet sand to build a sandcastle is easier than using dry sand, Bonn said. ^=^

“But, there is a delicate balance, the researchers found. "If you use dry sand, it won't work as well, but if the sand is too wet, it won't work either," Bonn said. "There's an optimum stiffness." The amount of water necessary depends on the type of sand, he added, but typically the optimal amount falls between 2 percent and 5 percent of the volume of sand. "It turns out that wetting Egyptian desert sand can reduce the friction by quite a bit, which implies you need only half of the people to pull a sledge on wet sand, compared to dry sand," Bonn said.” The study was published April 29, 2014 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last Updated August 2024