Home | Category: Art and Architecture

MESOPOTAMIAN ARCHITECTURE

Because of a lack of timber and stone, most buildings in Mesopotamia were made from mud bricks held together with plaited layers of reeds. There were few trees or even big rocks in the regions settled by the Sumerians, Babylonians and Assyrians. The most readily available materials were sand and clay and reeds from marshes. Even bricks that had been fire-baked deteriorated relatively quickly. Consequently very little of the ancient cities remain except for some foundations.

The Mesopotamians used asphalt as a building material 5000 years ago and were thus the first people to use petroleum. The Sumerians used bitumen mortar. In Ur mud bricks were bound together with asphalt-like bitumen. The sticky black substance helped preserve structures such as the ziggurat of Ur. The tar was one of the first uses of southern Iraq's oil fields.

In 1998, Dr. Elizabeth Stone from the University of New York at Stoney Brook announced that Mesopotamians in the city of Mashkan-shapir in southern Iraq used artificial stone as a building material. The basalt-like artificial rock was similar to slag produced in the production of iron and steel. It was made into slabs, some of which were 30 inches long, 2 inches thick and 16 inches wide. Scientists theorize the technology for making the artificial rocks — made by heating soils to intense heat — was pioneered by artisans who learned about the process from making metals and pottery.

See Separate Article: MESOPOTAMIAN HOMES, FURNITURE AND POSSESSIONS africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Mesopotamia: Ancient Art and Architecture” by Bahrani Zainab (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Art and Architecture of Mesopotamia” by Giovanni Curatola, Jean-Daniel Forest, Nathalie Gallois (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Earth Architecture: Past, Present, Future” by Jean Dethier (2020) Amazon.com;

“Architecture and Linear Measurement during the Ubaid Period in Mesopotamia” (BAR International) by Sam Kubba (1998) Amazon.com;

“Ziggurats of Ur: Echoes from Mesopotamia's Past”

by Sylvia D. Graham (2025) Amazon.com;

“Ziggurat: The Sacred Tower” by Theodor Dombart, Safaa H Hashim Amazon.com;

“House Most High: The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia (Mesopotamian Civilizations)

by Andrew R. George (1993) Amazon.com;

“Temples of Enterprise: Creating Economic Order in the Bronze Age Near East”

by Michael Hudson (2024) Amazon.com;

“Nippur V: The Area WF Sounding: The Early Dynastic to Akkadian Transition (Oriental Institute Publications) by Augusta McMahon , McGuire Gibson, et al. (2006) Amazon.com;

“Nippur IV: The Early Neo-Babylonian Governor's Archive from Nippur (Oriental Institute Publications) by Steven W. Cole (1996) Amazon.com;

“The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion” by Thorkild Jacobsen (1976) Amazon.com;

“The Temple of Ningirsu: The Culture of the Sacred in Mesopotamia” by Sébastien Rey (2024) Amazon.com;

“For the Gods of Girsu: City-State Formation in Ancient Sumer” by Sébastien Rey (2016) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Architecture: Mesopotamia, Egypt, Crete, Greece”

by Seton Lloyd , Hans Wolfgang Muller, et al. (1974) Amazon.com;

“Houses and Households in Ancient Mesopotamia”: Papers Read at the 40th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Leiden, July 5-8, 1993 (Pihans) Paperback – Illustrated, December 31, 1996 by KR Veenhof Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City“ by Gwendolyn Leick (2001) Amazon.com;

“Cornerstone: The Birth of the City in Mesopotamia” by Pedro Azara and Jeffrey Swartz (2015) Amazon.com;

“Early Urbanizations in the Levant: A Regional Narrative” by Raphael Greenberg (2002) Amazon.com;

Babylonian and Assyrian Architecture

The architecture of Babylonia and Assyrians was dependent on the nature of their region. In the alluvial plain no stone was procurable; clay, on the other hand, was everywhere. All buildings, accordingly, were constructed of clay bricks, baked in the sun, and bonded together with cement of the same material; their roofs were of wood, supported, not unfrequently, by the stems of the palm. The palm stems, in time, became pillars, and Babylonia was thus the birthplace of columnar architecture. It was also the birthplace of decorated walls.

Assur in Assyria It was needful to cover the sun-dried bricks with plaster, for the sake both of their preservation and of appearance. This was the origin of the stucco with which the walls were overlaid, and which came in time to be ornamented with painting. Ezekiel refers to the figures, portrayed in vermilion, which adorned the walls of the houses of the rich.

The temple and house were alike erected on a platform of brick or earth. This was rendered necessary by the marshy soil of Babylonia and the inundations to which it was exposed. The houses, indeed, generally found the platform already prepared for them by the ruins of the buildings which had previously stood on the same spot. Sun-dried brick quickly disintegrates, and a deserted house soon became a mound of dirt. In this way the villages and towns of Babylonia gradually rose in height, forming a tel or mound on which the houses of a later age could be erected.

In contrast to Babylonia the younger kingdom of Assyria was a land of stone. But the culture of Assyria was derived from Babylonia, and the architectural fashions of Babylonia were accordingly followed even when stone took the place of brick. The platform, which was as necessary in Babylonia as it was unnecessary in Assyria, was nevertheless servilely copied, and palaces and temples were piled upon it like those of the Babylonians. The ornamentation of the Babylonian walls was imitated in stone, the rooms being adorned with a sculptured dado, the bas-reliefs of which were painted in bright colors. Even the fantastic shapes of the Babylonian columns were reproduced in stone. Brick, too, was largely used; in fact, the stone served for the most part merely as a facing, to ornament rather than strengthen the walls.

Babylonian Columns and Architectural Decoration

The upright palm stems of Babylonian, as we said, became columns, which were imitated first in brick and then in stone. Babylonia was thus the birthplace of columnar architecture, and in the course of centuries columns of almost every conceivable shape and kind came to be invented. Sometimes they were made to stand on the backs of animals, sometimes the animal formed the capital. The column which rested against the wall passed into a brick pilaster, and this again assumed various forms. The monotony of the wall itself was disguised in different ways. The pilaster served to break it, and the walls of the early Chaldean temples are accordingly often broken up into a series of recessed panels, the sides of which are formed by square pilasters. Clay cones were also inserted in the wall and brilliantly colored, the colors being arranged in patterns. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

But the most common form of decoration was where the wall was covered with painted stucco. This, indeed, was the ordinary mode of ornamenting the internal walls of a building; a sort of dado ran round the lower part of them painted with the figures of men and animals, while the upper part was left in plain colors or decorated only with rosettes and similar designs. Ezekiel 6 refers to the figures of the Chaldeans portrayed in vermilion on the walls of their palaces, and the composite creatures of Babylonian mythology who were believed to represent the first imperfect attempts at creation were depicted on the walls of the temple of Bel.

Among the tablets which have been found at Tello are plans of the houses of the age of Sargon of Akkad. The plans are for the most part drawn to scale, and the length and breadth of the rooms and courts contained in them are given. The rooms opened one into the other, and along one side of a house there usually ran a passage. One of the houses, for example, of which we have a plan, contained five rooms on the ground floor, two of which were the length of the house. The dimensions of the second of these is described as being 8 cubits in breadth and 1 gardu in length. The gardu was probably equivalent to 18 cubits or about 30 feet. In another case the plan is that of the house of the high priest of Lagas, and at the back of it the number of slaves living in it is stated as well as the number of workmen employed to build it. It was built, we are told, in the year when Naram-Sin, the son of Sargon, made the pavement of the temples of Bel at Nippur and of Ishtar at Nin-unu.

Bricks and Brickmaking in Ancient Mesopotamia

While it became necessary to ornament the plain mud wall of the house, the clay brick itself, when painted and protected by a glaze, was made into the best and most enduring of ornaments. The enamelled bricks of Chaldea and Assyria are among the most beautiful relics of Babylonian civilization that have survived to us, and those which adorned the Persian palace of Susa, and are now in the Museum of the Louvre, are unsurpassed by the most elaborate productions of modern skill. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Our enumeration of Babylonian trades would not be complete without mention being made of that of the brick-maker. The manufacture of bricks was indeed one of the chief industries of the country, and the brick-maker took the position which would be taken by the mason elsewhere. He erected all the buildings of Babylonia. The walls of the temples themselves were of brick. Even in Assyria, where stone was more plentiful than in Babylonians , the slavish imitation of Babylonian models caused brick to remain the chief building material of a kingdom where stone was plentiful and clay comparatively scarce.

The brick-yards stood on the outskirts of the cities, where the ground was low and where a thick bed of reeds grew in a pond or marsh. These reeds were an important requisite for the brick-maker's art; when dried they formed a bed on which the bricks rested while they were being baked by the sun; cut into small pieces they were mixed with the clay in order to bind it together; and if the bricks were burnt in a kiln the reeds were used as fuel. They were accordingly artificially cultivated, and fetched high prices.

Wood in Mesopotamian Architecture

The carpenter's trade is another handicraft to which there is frequent allusion in the texts. Already, before the days of Sargon of Akkad, beams of wood were fetched from distant lands for the temples and palaces of Chaldea. Cedar was brought from the mountains of Amanus and Lebanon, and other trees from Elam. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The palm could be used for purely architectural purposes, for boarding the crude bricks of the walls together, or to serve as the rafters of the roof, but it was unsuitable for doors or for the wooden panels with which the chambers of the temple or palace were often lined. For such purposes the cedar was considered best, and burnt panels of it have been found in the sanctuary of Ingurisa at Tello. Down to the latest days panels of wood were valuable in Babylonia, and we find it stipulated in the leases of houses that the lessee shall be allowed to remove the doors he has put up at his own expense.

Musukkannu = Sisham Tree (Dalbergia sisso) was a wood imported from the east and used extensively in building. Chosen because it is an “everlasting wood.” Said to reproduce by sending out shoots from the root. Shisham is a good match for this word because its heartwood is known for its durability and hardness. Its current natural range is from Afghanistan to Bhutan but in times past, its range extended west and south into Iran.

Mesopotamian Temples

Sargon II palace in Dur-Sharrukin

In Mesopotamia temples were conceived as houses of god they housed, comparable to the houses of a noble or king. The temple housed the statue of the god, thought to contain the essence of the god. The temple building itself, and its symbolism, was considered a reflection of the cosmic abode of the god. The rites of worship consisted mainly in ministering to the physical needs of the gods. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

Temples were often the most central and important buildings in Mesopotamian city states. They were usually devoted to individual deities and could be quite elaborate if the city was rich. The largest temples were ziggurats (see Below).

Morris Jastrow said: “In like manner, the “house” motif prevails in the Babylonian and the Assyrian sanctuaries. Temple and palace adjoin one another in the great centres of the north and south. The temple is the palace of the deity, and the royal palace is the temple of the god’s representative on earth—who as king retains throughout all periods of Babylonian and Assyrian history traces of his original position as the “lieutenant,” or even the embodiment of god—a kind of alter ego of god, the god’s vicegerent on earth. The term which in Babylonian designates more specifically the palace, êkallu, i.e ., “great-house,” becomes in Hebrew, under the form hekhal, one of the designations of Jahweh’s sanctuary in Jerusalem. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“Temple and palace are almost interchangeable terms. Both are essentially houses, and every temple in Babylonia and Assyria bore a name which contained as one of its elements the word “house.” The ruler, embodying, originally, what we should designate as both civil and religious functions, was god, priest, and king in one. We have seen that the kings were in the earlier period often designated as divine beings: they regarded themselves as either directly descended from gods or as “named” by them, i.e., created by them for the office of king. To the latest days they could perform sacrifices—the distinct prerogative of the priests— and among their titles both in ancient and in later days, “priest” is frequently included.

See Separate Article: MESOPOTAMIAN TEMPLES africame.factsanddetails.com

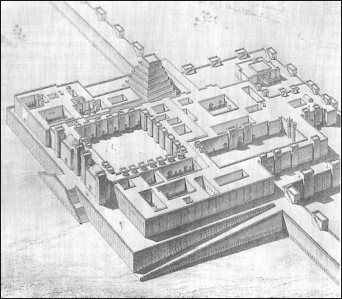

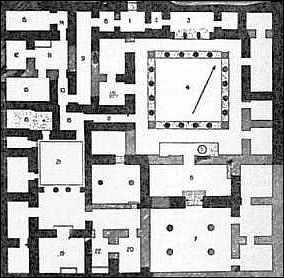

Mesopotamian Temple Layout

Layout of the Temple of Nippur

Mesopotamian temple usually contained a central shrine with a statute of the deity placed on a pedestal before an altar. The temples were watched over by priests and priestesses that lived in apartment in the temple. On the temple grounds were other quarters for officials, accountants, musicians and custodians as well as structures that held treasures, weapons and grain.

Sumerian pilgrims visited temples honoring Anau in Uruk and Enlil in Nippur. The largest temple in Mesopotamia was a temple honoring Marduk in Babylon. Inside was golden statue of statues of Marduk that weighed perhaps 5,000 pounds and 55 shrines devoted to lower echelon gods. The 200 foot long, 70-foot high ziggurat built in Ur had three platforms, each a different color, and a silver shrine at the top. [“World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Mesopotamia temples often had off center entrances so that common people could catch a glimpse of the inner sanctuary when they looked inside. Temples in Uruk, Ashur and Babylon all have this feature.

Herodotus on the Great Temple in Babylon

Herodotus wrote in “The History of the Persian Wars” ( c. 430 B.C.): “In the one stood the palace of the kings, surrounded by a wall of great strength and size: in the other was the sacred precinct of Jupiter Belus [Bel], a square enclosure two furlongs each way, with gates of solid brass; which was also remaining in my time. In the middle of the precinct there was a tower of solid masonry, a furlong in length and breadth, upon which was raised a second tower, and on that a third, and so on up to eight. The ascent to the top is on the outside, by a path which winds round all the towers. [Source: Herodotus, “The History”, translated by George Rawlinson, (New York: Dutton & Co., 1862]

“When one is about half-way up, one finds a resting-place and seats, where persons are wont to sit some time on their way to the summit. On the topmost tower there is a spacious temple, and inside the temple stands a couch of unusual size, richly adorned, with a golden table by its side. There is no statue of any kind set up in the place, nor is the chamber occupied of nights by any one but a single native woman, who, as the Chaldaeans, the priests of this god, affirm, is chosen for himself by the deity out of all the women of the land. I.182: They also declare — but I for my part do not credit it — that the god comes down in person into this chamber, and sleeps upon the couch. This is like the story told by the Egyptians of what takes place in their city of Thebes, where a woman always passes the night in the temple of the Theban Jupiter [Amon-Ra].

“In each case the woman is said to be debarred all intercourse with men. It is also like the custom of Patara, in Lycia, where the priestess who delivers the oracles, during the time that she is so employed — for at Patara there is not always an oracle — is shut up in the temple every night.I.183: Below, in the same precinct, there is a second temple, in which is a sitting figure of Jupiter [Marduk], all of gold. Before the figure stands a large golden table, and the throne whereon it sits, and the base on which the throne is placed, are likewise of gold.

“The Chaldaeans told me that all the gold together was eight hundred talents' weight. Outside the temple are two altars, one of solid gold, on which it is only lawful to offer sucklings; the other a common altar, but of great size, on which the full-grown animals are sacrificed. It is also on the great altar that the Chaldaeans burn the frankincense, which is offered to the amount of a thousand talents' weight, every year, at the festival of the God. In the time of Cyrus there was likewise in this temple a figure of a man, twelve cubits high, entirely of solid gold. I myself did not see this figure, but I relate what the Chaldaeans report concerning it. Darius, the son of Hystaspes, plotted to carry the statue off, but had not the hardihood to lay his hands upon it. Xerxes, however, the son of Darius, killed the priest who forbade him to move the statue, and took it away. Besides the ornaments which I have mentioned, there are a large number of private offerings in this holy precinct.” I.184:

Babylon

Temple Architecture in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: “The present ruined condition of the temples of Babylonia and Assyria makes it difficult to obtain an accurate idea of their construction; and a note of warning must be sounded against reconstructions, made on the basis of earlier excavations, which are, in almost all respects, purely fanciful. Thanks, however, to the careful work done by the German expedition at Ashur—the old capital of Assyria—our knowledge of details has been considerably extended; and since the religious architecture of Assyria by the force of tradition follows Babylonian models, except in the more liberal use of stone instead of bricks, the results of the excavations and investigations of the temple constructions of Ashur may be regarded as typical for Babylonian edifices as well. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“The “house” motif , which, we have seen, dominated the construction of temples, led to the setting apart of a special room to receive the image of the deity for whom the edifice was erected as a dwelling-place. The private quarters of the deity constituted the “holy of holies,” and this was naturally placed in the remotest part of the edifice. To this room, known as “the sacred chamber,” only the priests and kings had access; they alone might venture into the presence of the deity. It was separated from the rest of the building by an enclosure which marked the boundary between the “holy of holies” and the long hall or court where the worshippers assembled. Outside of this court there was a second one, in which, presumably, the business affairs of the temple were conducted. Grouped around these two courts were the apartments of the priests, the school, and the archive rooms, as well as the quarters for the temple stores. In the case of the larger centres, we must furthermore suppose many special buildings for the various needs of the religious household, stalls for the animals, workshops and booths for the manufacture of temple utensils, fabrics, and votive offerings, quarters for the tribunals, offices of the notaries, and the like.”

Inanna Temple ruins On the Stage Tower at Samarra, Jastrow said: “Dating from the 9th century A.D. and built of hard stone; it is still standing at Samarra, a settlement on the Tigris, and used as a minaret in connection with an adjoining mosque. The shape is directly derived from the old Babylonian (or Sumerian) Zikkurats and may be regarded as typical of these constructions. In most mosques, the minaret is directly attached to the main building like the tower or steeple of a church, but there are some which still illustrate the originally independent character of the tower.”

The Temple of Enlil at Nippur is regarded as typical for sacred edifices in Babylonia. The outer court and inner court are essentially parallel in size and shape. “The Zikkurat or stage tower is at the back of the inner court. The narrower section- represents the sacred chamber (or the approach to it) in which the image of Enlil stood. In the outer court, Bi represents one of the smaller shrines of which there were many within the sacred area to the gods and goddesses associated with the cult of Enlil and Ninlil. “

The Temple of Anu and Adad at Ashur “was originally built in honour of Anu, the solar deity (who is replaced by Ashur) but at a very early date, Adad (or Ramman) was associated with him. The two temples, consistently referred to in the Assyrian inscriptions as the “Temple of Anu and Adad,” have a large entrance court in common. Behind this court lie the two temples proper, each having (a) a broad outer court, (b) an oblong inner court, leading (c) to the sacred chamber where the images of Anu-Ashur and Adad, respectively, stood. This deviation from the Babylonian model, ' a broad outer and an oblong inner court instead of two practically parallel courts, is typical of Assyrian scared architecture. Each temple has its Zikkurat immediately adjoining it.”

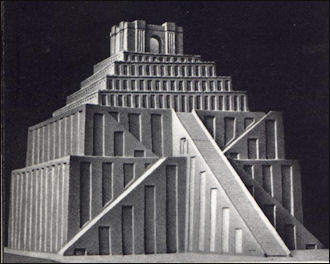

Ziggurats

The largest Sumerian and Mesopotamian structures were ziggurats — somewhat tower-like stepped pyramids made from mud brick and topped by temples to gods and goddess. They first appeared around 3500 B.C. In ancient times, every major Mesopotamian city had at least one.

In the forth century an Egyptian claimed that ziggurats "had been built by giants who wished to climb up to heaven. For this impious folly some were struck by thunderbolts; others, at God's command, were afterwards unable to recognize each other; all the rest fell headlong into the island of Crete, whither God in His wrath had hurled them."

Ziggurat means both the summit of a mountain and man-made tower. The Babylonians described them as a "Link Between Heaven and Earth." There are no mountains in Mesopotamia. Scholars believe ziggurats were built as artificial mountains to help man reach the gods and the gods reach man.

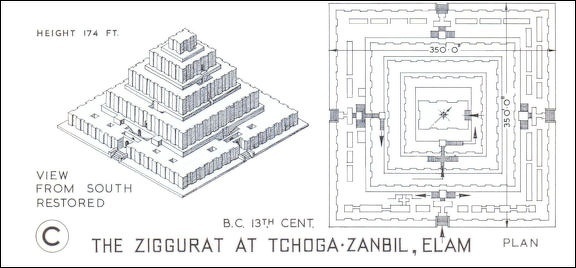

The remains of 33 ziggurats have survived until the 21st century. Since ziggurats were made of mud bricks they held up less against the ravages of time than the Pyramids of Egypt, which were built of stone. The Ziggurat of Choga Zambil (19 miles from Haft Tepe, Iran) is the world's largest ziggurat. Its outer base is 244-x-344 feet and the "fifth box" — 164 feet above the base — measures 92-x-92-feet. One of the most famous ziggurats — the one in Samarra, Iraq — is not a ziggurat at all but the minaret of an A.D. 8th century mosque.

See Separate Article: ZIGGURATS: SIZE, ARCHITECTURE AND THE TOWER OF BABEL africame.factsanddetails.com

Temple Construction and Babylonian-Assyrian Rulers

Sumerian Ziggurat Morris Jastrow said: “The history of the Babylonian and Assyrian temples and their zikkarats furnishes an index to the religious fervour of the rulers. The records left by rulers of the oldest period are in the main votive inscriptions, indicative of their activity in building or rebuilding religious edifices. Conquerors, like Sargon and Ham-murapi, are proud of the title of “builder” of this or that temple; and their example is followed by the war-lords of Assyria, who interrupt the narration of their military exploits by detailed accounts of their pious labours in connection with the great sanctuaries of the country. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“Taking the temples at Nippur, Sip-par, Babylon, and Ashur as typical examples, we find a long chain of rulers leaving records of their building activities in these centres. Kings of Kish, Uruk, Ur, and Agade vie with the rulers of Babylon and Nineveh in paying homage to the “mountain house” at Nippur, repairing the decayed portions, extending its dimensions, and adding to the mass of its zikkurat. They dedicate the spoils of war to Enlil and deposit votive offerings in his shrine. From Sargon of Agade to Ashurbanapal of Nineveh, E-Kur continued to be a place of pilgrimage whither the rulers went to acknowledge the authority of Enlil, and of his consort Ninlil. Long indeed after the tutelary deity of the city had been forgotten, the city retained its odour of sanctity, and the temple area became a burial-place for Jews and Christians, who bear witness to the persistence of time-worn beliefs by inscribing in Aramaic dialects on clay bowls incantations against the demons of ancient Babylonia, belief in whose power to inflict injury on the dead had not yet evaporated in the sixth and seventh centuries of our era.

“The last king of Babylonia, Nabonnedos (555-539 B.C.), who aroused the hostility of Marduk and the priests of Esagila by his preference for the sun-god, gives us, in connection with his restoration of the temple of Shamash at Sippar, the history of that time-honoured sanctuary. As an act of piety to the memory of past builders, it became an established duty in Babylonia to unearth the old foundation stone of a temple before the work of restoration could be begun. On that stone the name of the builder was inscribed, generally with a curse on him who removed it or substituted his name for the one there written. After many efforts the workmen of Na-bonnedos succeeded in finding the stone, and the king tells us how he trembled with excitement and awe when he read on it the name of Naram-Sin. Incidentally, he gives us the date of Naram-Sin, who, he says, ruled 3200 years before him. It is one of the many great triumphs of modern investigation that we can actually correct the scribes of Naram-Sin, who made a mistake of over 1000 years.

“Nabonnedos mentions also the names of Hammurabi and Burna-buriash as among those who, many centuries before him, repaired this ancient edifice, after, it had fallen into decay through lapse of ages. Toward the end of the Kassite dynasty (ca . 1200 B.C.) nomadic hordes devastated the country, and the cult suffered a long interruption, but E-Barra was restored to much of its former grandeur by Nebopaliddin in the ninth century, and from this time down to the time of Nabonnedos, it continued to be an object of great care on the part of both Assyrian and Babylonian kings. Esarhaddon, Ashurbanapal, Nabopolassar, and Nebuchadnezzar are among those who during this later period left records of their activity at E-Barra, the “house of splendour” at Sippar.”

Enki Builds the Temple of the God Ea in Eridu.

“Enki Builds the E-engurra, the Temple of the God Ea in Eridu,” is a myth that tells how Enki built a house (temple) for himself in Eridu, the oldest city in Sumer according to tradition, the first of five cities founded before the Great Flood. The temple, decorated with silver, lapis lazuli, carnelian and gold, was established on the bank of a river, where its foundations reached deep into the underground sweet, fertilising waters, called the apsu. The temple had magical qualities: the brickwork gave Enki advice, while the surrounding reed fences roared like a bull. The roof-beam was shaped like the bull of heaven, and a kion gripping a man formed the gateway. The overall effect was described as a lusty bull. The bustle of activity there was compared to the drama of a river rising during a flood. [Source: Kramer, Samuel Noah “Sumerian Mythology,” University of Pennsylvania Press, West Port, Connecticut, 1988 Babylonia Index, piney.com]

“Enki Builds the E-engurra” goes: “ Enki filled the building with lyres, drums and every other kind of musical instruments. Surrounding the temple was a delightful garden full of fruit trees, with birds singing all around and frolicking carp playing among the reeds in the streams. After finishing the construction of the E-engurra, the temple, Enki called up the beat of the ala and the uh drums and set out by barge to Nippur, in order to receive the other godsy blessings. The fish danced before him on the way to Nippur, and Enki slaughtered several oxen and sheep for the feast to come.

“Once in Nippur, Enki started preparing the feast. Paying attention to protocol, Anu was at the head of the group, with Enlil beside him and the goddess Nintu in a seat of honour nearby. In the happy cellebration that followed, all the great gods pronounced blessings on Enki's new home, and Anu stated:" My son Enki has made his temple.... grow from the ground like a mountain". After the water of creation had ben decreed, After the name hegal (abundance) born in heaven, Like plant and herb had clothed the land, The lord of the abyss, the king Enki,

“Enki the Lord who decrees the fates, Built his house of silver and lapis lazuli; Its silver and lapis lazuli, like sparkling light, The father fashioned fittingly in the abyss. The creatures of bright countenances and wise, coming forth from the abyss, Stood all about the lord Nudimmud; The pure house he built He ornamented it greatly with gold, In Eridu he built the house of water-bank, Its brickwork, word-uttering, advice-giving, Its... like an ox roaring, The house of Enki, the oracles uttering. [Follows a long passage in which Isimud, Enki's counsellor/prime minister, sings the praises of the sea-house.]

“Then Enki raises the city of Eridu from the abyss and makes it float over the water like a lofty mountain. Its green fruit-bearing gardens he fills with birds; fishes too he makes abundant. Enki is now ready to proceed by boat to Nippur, where he will obtain Enlil's blessings for his newly built city and temple. He therefore rises from the abyss:) When Enki rises, the fish.... rise, The abyss stands in wonder, In the sea joy enters, Fear comes over the deep, Terror holds the exalted river, The Euphrates, the South Wind lifts it in waves.

Enki seats himself in his boat and first arrives in Eridu itself. In Eridu, he slaughters many oxen and sheep before proceeding to Nippur. Upon his arrival, a feast is prepared for all gods and Enlil in special: Enki in the shrine Nippur, Gives his brother Enlil bread to eat, In the first place he seated Anu (the Skyfather), Next to Anu he seated Enlil, Nintu he seated at the big side, The Anunnaki seated themselves one after the other. Enlil says to the Anunnaki: " Ye great gods who are standing about, My brother has built a house, the king Enki; Eridu, like a mountain, he has raised up from the earth, In a good place he has built it. Eridu, the clean place, where none may enter, The house built of silver, adorned with lapis lazuli, The house directed by the seven lyre-songs given over to incantation, With pure songs.... The abyss, the shrine of the goodness of Enki, befitting the divine decrees, Eridu, the pure house having been built, O Enki, praise!"”

Nippur Temple

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024