Home | Category: Art and Architecture

ZIGGURATS

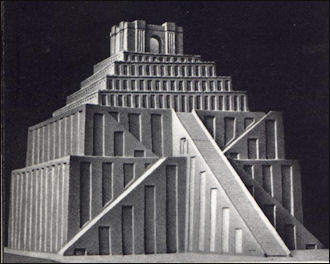

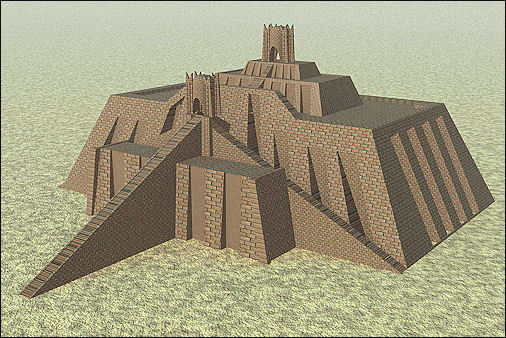

Sumerian Ziggurat The largest Sumerian and Mesopotamian structures were ziggurats — somewhat tower-like stepped pyramids made from mud brick and topped by temples to gods and goddess. They first appeared around 3500 B.C. In ancient times, every major Mesopotamian city had at least one.

In the forth century an Egyptian claimed that ziggurats "had been built by giants who wished to climb up to heaven. For this impious folly some were struck by thunderbolts; others, at God's command, were afterwards unable to recognize each other; all the rest fell headlong into the island of Crete, whither God in His wrath had hurled them."

Ziggurat means both the summit of a mountain and man-made tower. The Babylonians described them as a "Link Between Heaven and Earth." There are no mountains in Mesopotamia. Scholars believe ziggurats were built as artificial mountains to help man reach the gods and the gods reach man.

The remains of 33 ziggurats have survived until the 21st century. Since ziggurats were made of mud bricks they held up less against the ravages of time than the Pyramids of Egypt, which were built of stone. The Ziggurat of Choga Zambil (19 miles from Haft Tepe, Iran) is the world's largest ziggurat. Its outer base is 244-x-344 feet and the "fifth box" — 164 feet above the base — measures 92-x-92-feet. One of the most famous ziggurats — the one in Samarra, Iraq — is not a ziggurat at all but the minaret of an A.D. 8th century mosque.

The oldest structure in reasonably good condition left from ancient Mesopotamia is the 4500 year-old Ziggurat of King Urnammu in Ur. It originally consisted of three levels, of which only the third remains. It looks sort of like a 50-foot wall castle wall filled in with dirt and ascended by a staircase. The main ziggurat of Ur was dedicated to the moon god Nanna. It rises 65 feet from a 135-by-200-foot base and is 4,100 year old. After the invasion of Iraq by the United States it was inclosed within a U.S. military base.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ziggurats of Ur: Echoes from Mesopotamia's Past”

by Sylvia D. Graham (2025) Amazon.com;

“Ziggurat: The Sacred Tower” by Theodor Dombart, Safaa H Hashim Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: Ancient Art and Architecture” by Bahrani Zainab (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Art and Architecture of Mesopotamia” by Giovanni Curatola, Jean-Daniel Forest, Nathalie Gallois (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Earth Architecture: Past, Present, Future” by Jean Dethier (2020) Amazon.com;

“Architecture and Linear Measurement during the Ubaid Period in Mesopotamia” (BAR International) by Sam Kubba (1998) Amazon.com;

“House Most High: The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia (Mesopotamian Civilizations)

by Andrew R. George (1993) Amazon.com;

“Temples of Enterprise: Creating Economic Order in the Bronze Age Near East”

by Michael Hudson (2024) Amazon.com;

“Nippur V: The Area WF Sounding: The Early Dynastic to Akkadian Transition (Oriental Institute Publications) by Augusta McMahon , McGuire Gibson, et al. (2006) Amazon.com;

“Nippur IV: The Early Neo-Babylonian Governor's Archive from Nippur (Oriental Institute Publications) by Steven W. Cole (1996) Amazon.com;

“The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion” by Thorkild Jacobsen (1976) Amazon.com;

“The Temple of Ningirsu: The Culture of the Sacred in Mesopotamia” by Sébastien Rey (2024) Amazon.com;

“For the Gods of Girsu: City-State Formation in Ancient Sumer” by Sébastien Rey (2016) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Architecture: Mesopotamia, Egypt, Crete, Greece”

by Seton Lloyd , Hans Wolfgang Muller, et al. (1974) Amazon.com;

“Houses and Households in Ancient Mesopotamia”: Papers Read at the 40th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Leiden, July 5-8, 1993 (Pihans) Paperback – Illustrated, December 31, 1996 by KR Veenhof Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City“ by Gwendolyn Leick (2001) Amazon.com;

“Cornerstone: The Birth of the City in Mesopotamia” by Pedro Azara and Jeffrey Swartz (2015) Amazon.com;

“Early Urbanizations in the Levant: A Regional Narrative” by Raphael Greenberg (2002) Amazon.com;

Ziggurat Features

Morris Jastrow said: “A feature of the temple area in the large centres was a brick tower, formed by from two to seven superimposed stages, which stood near the temple proper. These towers were known as zikkurats —a term that has the sense of “high” places. Elaborate remains of the zikkurats at Nippur and at Ashur have been unearthed, and these together with the famous one at Borsippa, still towering above the mounds at that place, and currently believed among the natives to be the traditional tower of Babel, enable us to form a tolerably accurate idea of their construction. Huge and ungainly quadrangular masses of bricks, placed one above the other in stories diminishing in the square mass as they proceed upwards, these towers attained the height of about one hundred feet and at times more. The character of such a sacred edifice differs so entirely from the Babylonian temple proper, that, in order to account for its presence in Nippur, Lagash,Ur, Sippar, Larsa, Babylon, Borsippa, Ashur, Nineveh, and other places, we must perforce assume a second motif by the side of the “house” scheme of a temple. The height of these towers, as well as the diminishing mass of the stones, with a winding balustrade, or a direct ascent from one stage to the other up to the top, at once recalls the picture of a mountain. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“The semblance suggests that the motif must have originated with a people dwelling in a mountainous country, who placed the seats of their gods on the mountain-tops, as was so generally done by ancient peoples. The gods who are thus localised, however, are generally storm gods like Jahweh, who dwells on the top of Mt. Sinai—or according to another view on Mt. Seir,—or like Zeus on Mt. Olympus. The gods whose manifestations appear in the heavens—in the storm, in the thunder, and in the lightning—would naturally have their seats on high mountains whose tops, so frequently enveloped in clouds, would be regarded as forming a part of heaven. If this supposition be correct, we should furthermore be obliged to assume that the “mountain” motif was brought to the mountainless region of the Euphrates by a people entering the valley from some mountainous district.

“Since the zikkurats can be traced back to the Sumerian period (we find them in Gudea’s times and during the Sumerian dynasties of Ur), their introduction must be credited to the Sumerians, or to an equally ancient section of the population. We have seen that it is not possible to affirm positively that non-Semitic settlers were the earliest inhabitants of the Euphrates Valley; but the circumstance that where we find zikkurats in Semitic settlements (such as the minarets attached to the Mohammedan mosques), they can be traced back, as we shall presently see, to Babylonian prototypes, furnishes a strong presumption in favour of ascribing the “mountain” motif to Sumerian influence.”

Ziggurat of Ur

On the two ziggurats of the Anu-Adad Temple at Ashur, Jastrow said: “The temple being a double construction, one zikkurat or stage tower belongs to the Anu sanctuary, the other to the sanctuary of Adad. The construction of this stage tower may be traced back to the reign of Ashurreshishi I. (c. 1150 B.C.). It was rebuilt by Shalmaneser III. (858-824 b.c).

Purpose of Ziggurats

Morris Jastrow said: ““It is not without significance that the temple at Nippur, which is certainly a Sumerian settlement, and one of the oldest, bore the name E-Kur, “mountain-house,” and that Enlil, the chief deity of Nippur, bears the indications of a storm-god, whose dwelling should, probably, therefore, be on a mountain. Herodotus is authority for the statement that there was a small shrine at the top of the zikkurat , in which there was a statue of the god in whose honour the tower was built. This shrine, therefore, represented the dwelling of the god, and corresponded to the sacred chamber in the temple proper. To ascend the zikkurat would thus be equivalent to paying a visit to the god; and we have every reason to believe that the ascent of the zikkurat formed a part of the ceremonies connected with the cult, just as the Jewish pilgrims ascended Mt. Zion at Jerusalem to pay their homage to Jahweh, who was there enshrined after the people had moved away from Mt. Sinai and Mt. Seir. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“There is no reason to assume that these towers were ever used for astronomical purposes, as has been frequently asserted. Had this been the case, we should long ere this have found reference to the fact in some inscription. References to an observatory for the study of the heavens, known as the bit tamarti, i.e., “house of observation,” are not infrequent, blit nowhere is there any indication that the zikkurats were used for that purpose. They must have been regarded as too sacred to be frequently visited, even by the priests. Access to them was rather complicated, and for observations needed for astrological divination a high eminence was not required. Still more groundless, and hardly worthy of serious consideration is the supposition that it was customary to bury the dead at the base of the zikkurat , which in this case would be a Babylonian equivalent of the Egyptian pyramid, namely, as the tomb of monarchs and of grand personages.

“On the other hand, the imitation of a mountain suggested a further symbolism in the zikkurats, which reveals itself in the names given to some of them. While no special stress seems, at any time, to have been laid on the number of stories or stages of which a zikkurat consisted, the chief aim of the builders being the construction of a high mass, seven stages seems to have become the normal number, after a certain period. There seems to be no reason to doubt that this number was chosen to correspond to the moon, sun, and five planets, which we have seen were the controlling factors in the Babylonian-Assyrian astrology. Gudea describes the zikkurat at Lagash known as E-Pa as the “house of the seven divisions”; and from the still fuller designation of the tower at Borsippa as the “seven divisions of heaven and earth,” it would appear that in both cases there is a symbolical reference to the “seven planets,” as the moon, sun, and five planets were termed by the Babylonians themselves.

“Less probable is the interpretation of the name of the tower at Uruk as the “seven enclosures” (or possibly “groves”) as applying likewise to the seven planets, though to speak of the moon, sun, and five planets as “enclosures” would be a perfectly intelligible metaphor. That the symbolism of the zikkurats was carried any further, however, and each stage identified with one of the planets, may well be doubted, nor is it at all likely that the bricks of each stage had a different colour, corresponding to colours symbolically associated with the planets. Even if seven different colours were used in the construction, there is no evidence thus far that these colours were connected with the planets. Moreover, a valuable hint of one of the fundamental ideas associated with the zikkurat is to be found in the name given to the one at Larsa: “the house of the link of heaven and earth.”

“Attention has already been called to the fact that the heavens, according to the prevailing view of antiquity, were not elevated very far above the earth. The tops of the mountains were regarded as reaching into heaven,—in fact as belonging to the heavens. The zikkurat , therefore, as the imitation of the mountain, might well be called the “link” uniting earth to heaven. The name is of interest because of the light which it throws on the famous tale in Genesis (chap. xi.) of the building of the tower. To the Hebrew writers, particularly those who wrote under the influence of the religious ideals of the prophets, the ambitious aims of the great powers of antiquity—conquest, riches, large armies, brilliant courts, the pomp of royalty, and indulgence in luxury—were exceedingly distasteful. Their ideal was the agricultural life in small communities governed by a group of elders, and with the populace engaged in tilling the soil and in raising flocks,— living peacefully under the shade of the fig tree. In the view of these writers, even such a work as the temple of Solomon, built by foreign hands, in imitation of the grand structures of other nations, was not pleasing in the eyes of Jahweh, whose preference was for a simple tabernacle, built of wood without the use of hewn stones and iron,—both of which represented innovations. These writers were what we should call “old-fashioned,”—advocates of the simple life. They abominated, therefore, the large religious households of the Babylonians and Assyrians and particularly the high towers which were the “skyscrapers” of antiquity.”

Ziggurat of Ur

Describing the well-preserved ziggurat in Ur, Michael Taylor wrote in Archaeological magazine, “The classic step-pyramid temple consists of two tiers stacked one atop the other, with three converging staircases in front. It is six stories tall and its footprint would fill more than half a football field. In an otherwise barren landscape, it exerts an almost gravitational pull, drawing visitors up the steep yellow steps. It is a great artificial mountain of brick, and long ago it gave the Mesopotamians a brush with their gods.

The brickwork of the ziggurat attests to the kings' desire to create a lasting monument to their empire. The bitumen mortar — one of the first uses of southern Iraq's vast oil fields — is still visible between the burnt bricks. The sticky black substance, today a source of the region's instability and violence, once literally bound this civilization together. The use of bitumen as mortar and pavement has helped waterproof the otherwise fragile Sumerian mud-bricks, ensuring that the structures endured for millennia.

The ziggurat has always been an important symbol for this region, and two later rulers attempted to adopt it as their own through reconstruction projects. The first was Nabonidus, the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (the second was Saddam Hussein). A pious ruler, Nabonidus restored a number of ancient temples in his realm during the sixth century B.C. The exact details of his reconstruction are unclear, but it seems that he built some enormous structure on top of the massive burnt-brick base left by Ur-Nammu, replacing what had been a modest shrine. But where Ur-Nammu used durable bitumen mortar, Nabonidus' builders used ordinary cement. Wind and rain have since reduced his later structure to the heap of rubble that now sits atop the ziggurat. Nabonidus was not rewarded for his piety — he was deposed by invading Persians in 539 B.C. Over the next 2,500 years, Nabonidus' contribution fell to ruin, while Ur-Nammu's original held up.

Tower of Babel

The most famous example of ziggurat is the biblical Tower of Babel, which, according to the Old Testament and ancient Jewish and Christian scholars was an effort by mankind to reach the heavens with a ladder-like structure and enter the kingdom of God without God's approval. Sometimes it is linked with Jacob, the grandson of Abraham, who "dreamed, and behold a ladder set up to the earth, and the top it reached to heaven: and behold the angels of God ascending and descending it."

The phrase "the Tower of Babel" does not actually appear in the Bible; it is always, "the city and its tower." Several generations after the Great Flood of Noah’s time humanity came together, Genesis 11:1-9 reads: “And the whole earth was of one language, and of one speech. And it came to pass, as they journeyed from the east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar; and they dwelt there. And they said one to another, Go to, let us make brick, and burn them thoroughly. And they had brick for stone, and slime had they for mortar. And they said, Go to, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.

There is no proof or archaeological evidence that the Tower of Babel really existed. Describing a ziggurat he saw in Babylon, the Greek historian Herodotus wrote in 460 B.C., "In the topmost tower there is a great temple, and in the temple is a great bed richly appointed, and beside it a golden table. No idol stands there. No one spends the night there save a woman of that country, designated by the god himself, so I was told by the Chaldeans, who are priests of that divinity."

See Separate Article: TOWER OF BABEL africame.factsanddetails.com

Tower of Babel

Ziggurat of Babylon

Describing a ziggurat he saw in Babylon, the Greek historian Herodotus wrote in 460 B.C., "In the topmost tower there is a great temple, and in the temple is a great bed richly appointed, and beside it a golden table. No idol stands there. No one spends the night there save a woman of that country, designated by the god himself, so I was told by the Chaldeans, who are priests of that divinity."

Herodotus described the Etemenanki ziggurat, dedicated to Marduk in the city and famously rebuilt by the 6th century B.C. by the Neo-Babylonians under Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II. Many modern scholars believe the biblical story of the Tower of Babel was likely influenced by Etemenanki during the Babylonian captivity of the Hebrews. According to UNESCO: “According to the tradition, several attempts were made to build the Tower, lastly by Nebuchadnezzar II. The bulk of the tower was built with unbaked bricks made by mixing chopped straw with clay and pouring the results into moulds. The bricks were joined in the construction by using bitumen, material imported from the Iranian plateau and used widely as a binding and coating material throughout the Mesopotamian plain. Following the fall of Babylon to Cyrus the Great of Persia in 539 BCE, the Tower of Babylon was probably gravely damaged, and left in a state of neglect and abandonment until 331 BCE, when the city was taken by Alexander the Great, who planned to rebuild the tower. At that time, most of the debris were removed in preparation for the reconstruction of the Tower, never actually implemented due to the sudden death of Alexander in Babylon. Babylon was excavated by Robert Koldeway between 1899 and 1917 on behalf of the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft. Excavations uncovered substantial remains of the time of the Neo-Babylonian Period including the Esagila and the Tower of Babylon. [Source: UNESCO World Heritage Sites, =]

Gerald A. Larue wrote in ““The tower of Babel story can be related to the ziggurats or temple towers of Mesopotamia. These huge, man-made mountains of sun-dried brick, faced with kiln-baked brick often in beautiful enamels, rose several hundred feet above the flat plains of Mesopotamia. Used in the worship of the various deities to whom they were consecrated, they seemed to J a fitting symbol of man's arrogant pride. Selecting the ziggurat at Babylon dedicated to Bel-Marduk, J describes the great building project as an attempt of man to invade heaven, which, in Near Eastern thought, was believed to be just above the zenith of the firmament. To thwart human ambitions, Yahweh caused men to speak in different languages, and because men who cannot speak together cannot work together, the project failed. This, J explained, was why mankind, descended from a common ancestor, Noah, spoke different languages. Once again J's delight in puns is demonstrated for God confused ( balel) man's speech at Babel, or as Dr. Moffatt's translation aptly puts it, the place "was called Babylonia" for there God "made a babble of the languages." [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org]

Muslim Minerets and Babylonian-Assyrian Ziggurats

Morris Jastrow said: “Tower and temple remain, through all periods of Babylonian-Assyrian history, the types of religious architecture and survive the fall of both countries. The survival of religious traditions, despite radical changes in outward forms, is illustrated by the adoption of the zikkurat by Islamism. At Samarra, about sixty miles above Bagdad, there survives to this day an almost perfect type of a Babylonian zikkurat, as a part of a Muslim mosque. Built about the middle of the ninth century of our era, and rising to a height of about one hundred and seventy feet, it has a winding ascent to the top, where in place of the sacred shrine for the god is the platform from which the muezzin calls the faithful to prayer. The god has been replaced by his servitor, and instead of the address belu rabu (“great lord”) with which it was customary to approach the deities of old, Allah akbar (“Allah is great”) is heard from the minarets —which, as will have become evident, are merely modified zikkurats. Arabic writers themselves trace the custom of building a minaret at the side of a mosque, or as an integral part of the sacred structure, to the zikkurat at Samarra; and the chain of evidence has recently been completed to show that the steeples of our modern churches are a further step in the evolution of the zikkurat, [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“In Babylonia and Assyria, temple and tower, once entirely distinct, show a tendency to unite. In the city of Ashur, the oldest temple, or rather double temple, dedicated to Anu and Adad, has a zikkurat on either side, each being directly attached to the respective temple or “house” of the deity. Elsewhere—as at Nippur—the zikkurat is close behind the temple, but even when adjacent the zikkurat remains an independent structure, and it is interesting to note that in the traditional forms of Christian architecture, the church tower retains this independent character. In Catholic countries where traditions are closely followed, it is provided that though the tower should be a part of the church, there must be no direct access from the one to the other.

“The opposition of the Hebrews to the allurements of Babylonian-Assyrian civilisation was strong enough to check the introduction of zikkurats into Palestine, but it could not prevent the imitation of the Assyrian temple in the days of Solomon. The type of religious edifice erected by this grand monarque of the Hebrews followed even in details the Assyrian model with its threefold division, the broad outer court, the oblong narrow inner court, and the “holy of holies,” where in place of the statue of the deity was the sacred box (or “Ark”) with the Cherubim over it as the symbol of Jahweh.”

Blue mosque in Istanbul

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2024