Home | Category: Religion / Art and Architecture

TEMPLES IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA

Temples were often the most central and important buildings in Mesopotamian city states. They were usually devoted to individual deities and could be quite elaborate if the city was rich. The largest temples were ziggurats (see Below).

Morris Jastrow said: “The “house” motif prevails in the Babylonian and the Assyrian sanctuaries. Temple and palace adjoin one another in the great centres of the north and south. The temple is the palace of the deity, and the royal palace is the temple of the god’s representative on earth—who as king retains throughout all periods of Babylonian and Assyrian history traces of his original position as the “lieutenant,” or even the embodiment of god—a kind of alter ego of god, the god’s vicegerent on earth. The term which in Babylonian designates more specifically the palace, êkallu, i.e ., “great-house,” becomes in Hebrew, under the form hekhal, one of the designations of Jahweh’s sanctuary in Jerusalem. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“Temple and palace are almost interchangeable terms. Both are essentially houses, and every temple in Babylonia and Assyria bore a name which contained as one of its elements the word “house.” The ruler, embodying, originally, what we should designate as both civil and religious functions, was god, priest, and king in one. We have seen that the kings were in the earlier period often designated as divine beings: they regarded themselves as either directly descended from gods or as “named” by them, i.e., created by them for the office of king. To the latest days they could perform sacrifices—the distinct prerogative of the priests— and among their titles both in ancient and in later days, “priest” is frequently included.

“With the differentiation of functions consequent upon political growth and religious advance the service of the god was committed to a special class of persons. Priests from being the attendants of the kings, became part of the religious household of the god. The two households, the civil and the religious, supplemented each other. Over the one presided the ruler, surrounded by a large and constantly growing retinue for whom quarters and provisions had to be found in the palace; at the head of the temple organisation stood the god or goddess, whose sanctuary grew in equal proportion, to accommodate those who were chosen to be servitors. Even the little shrines scattered throughout the Islamic Orient of to-day—commonly fitted up as tombs of saints, but often replacing the site of the dwelling-place of some ancient deity—have a place set aside for the servitor of the god,—the guardian of the sanctuary,—just as a private household has its quarters for the servants. As the temple organisation became enlarged, the apartments for the priests correspondingly increased. Supplementary edifices became necessary to accommodate the stores required for the priests and the cult. The temple grew into a temple-area, which, in the large religious centres, in time assumed the dimensions of an entire sacred quarter.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Temples of Enterprise: Creating Economic Order in the Bronze Age Near East”

by Michael Hudson (2024) Amazon.com;

“House Most High: The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia (Mesopotamian Civilizations)

by Andrew R. George (1993) Amazon.com;

“Nippur V: The Area WF Sounding: The Early Dynastic to Akkadian Transition (Oriental Institute Publications) by Augusta McMahon , McGuire Gibson, et al. (2006) Amazon.com;

“Nippur IV: The Early Neo-Babylonian Governor's Archive from Nippur (Oriental Institute Publications) by Steven W. Cole (1996) Amazon.com;

“The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion” by Thorkild Jacobsen (1976) Amazon.com;

“The Temple of Ningirsu: The Culture of the Sacred in Mesopotamia” by Sébastien Rey (2024) Amazon.com;

“Sumerian Hymns and Prayers to God Nin-Ib: From the Temple Library at Nippur”

by Hugo Radau (2022) Amazon.com;

“For the Gods of Girsu: City-State Formation in Ancient Sumer” by Sébastien Rey (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“A Handbook of Ancient Religions” by John R. Hinnells (2007) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: Ancient Art and Architecture” by Bahrani Zainab (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Art and Architecture of Mesopotamia” by Giovanni Curatola, Jean-Daniel Forest, Nathalie Gallois (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Earth Architecture: Past, Present, Future” by Jean Dethier (2020) Amazon.com;

“Ziggurats of Ur: Echoes from Mesopotamia's Past”

by Sylvia D. Graham (2025) Amazon.com;

“Ziggurat: The Sacred Tower” by Theodor Dombart, Safaa H Hashim Amazon.com;

Mesopotamian Gods and Temples

In Mesopotamia temples were conceived as houses of god they housed, comparable to the houses of a noble or king. The temple housed the statue of the god, thought to contain the essence of the god. The temple building itself, and its symbolism, was considered a reflection of the cosmic abode of the god. The rites of worship consisted mainly in ministering to the physical needs of the gods. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

Morris Jastrow said: “There is still another aspect of the temples of Babylonia and Assyria. We have already taken note of the tendency to group the chief gods and goddesses and many of the minor ones also around the main deity, in a large centre. A god like Enlil at Nippur, Shamash at Sippar, Ningirsu at Lagash, Sin at Ur, and Marduk at Babylon, is not only served-by a large body of priests, but, again, as in the case of the great ruler who gathers around his court the members of his official family, smaller sanctuaries were erected within the temple area at Nippur to Ninlil, Enlil’s consort, to Ninib, Nusku, Nergal, Ea, Sin, Shamash, Marduk, and others, all in order to emphasise the dominant position of Enlil. It is safe to state that in the zenith of Nippur’s glory all the important gods of the pantheon were represented in the cult at that place. We have a list of no less than thirteen sanctuaries at Lagash, and we may feel certain that they all stood within the sacred area around E-Ninnu, “house of fifty,” which was the name given to Ningirsu’s dwelling at that place. At the close of Babylonian history we find Nebuchadnezzar II. enumerating, among his numerous inscriptions, the shrines and sanctuaries grouped around E-Sagila, “the lofty house,” as Mar-duk’s temple at Babylon was called. His consort Sar-panit, his son Nebo, his father Ea, were represented, as were Sin, Shamash, Adad, Ishtar, Ninib and his consort Gula, Nergal and his consort Laz, and so on through a long list. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“There was no attempt made to assimilate the cult of these deities to that of Marduk, despite the tendency to heap upon the latter the attributes of all the gods. The shrines of these gods, bearing the same names as those of their sanctuaries in their own centres of worship, served to maintain the identity of the gods, while as a group around Marduk they illustrated and emphasised the subsidiary position which they occupied. In a measure, this extension of the “house” of a deity into a sacred quarter with dwellings for gods whose actual seat was elsewhere, displaced the original idea connected with a sanctuary, but kings also erected palaces for themselves in various places without endangering either the prestige or the conception of a central dwelling in the capital of the kingdom. The shrines of the gods within the sacred area of E-Sagila represented temporary abodes, or “embassies” as it were, and so it happened that even Marduk had a foreign sanctuary, e.g., at Borsippa to symbolise the close relationship between him and Nebo.

“The rulers of Assyria vied with those of the south in beautifying and enlarging the temples of their gods, and in constantly adding new structures; or rebuilding the old which had fallen into decay. The sacred quarter in the old capital at Ashur, and in the later capital at Nineveh, was studded with edifices, and the priests have left us lists of the many gods and goddesses “whose names were invoked,” as the phrase ran, in the temples of the capital.

Mesopotamian Temple Layout

Layout of the Temple of Nippur

Mesopotamian temple usually contained a central shrine with a statute of the deity placed on a pedestal before an altar. The temples were watched over by priests and priestesses that lived in apartment in the temple. On the temple grounds were other quarters for officials, accountants, musicians and custodians as well as structures that held treasures, weapons and grain.

Sumerian pilgrims visited temples honoring Anau in Uruk and Enlil in Nippur. The largest temple in Mesopotamia was a temple honoring Marduk in Babylon. Inside was golden statue of statues of Marduk that weighed perhaps 5,000 pounds and 55 shrines devoted to lower echelon gods. The 200 foot long, 70-foot high ziggurat built in Ur had three platforms, each a different color, and a silver shrine at the top. [“World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Mesopotamia temples often had off center entrances so that common people could catch a glimpse of the inner sanctuary when they looked inside. Temples in Uruk, Ashur and Babylon all have this feature.

See Separate Article: MESOPOTAMIAN ARCHITECTURE africame.factsanddetails.com

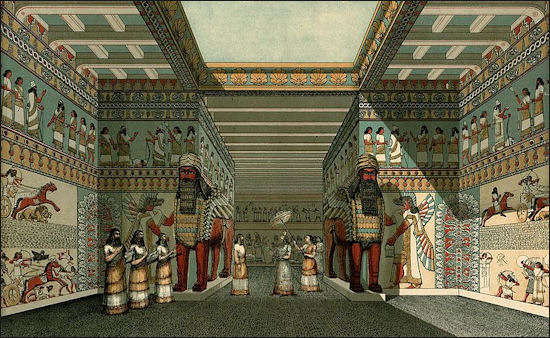

Inner Shrine of a Babylonian Temple

The chapel found by Mr. Hormund Rassam at Balawât, near Nineveh, gives us some idea of what the inner shrine of a temple was like. At its north-west end was an altar approached by steps, while in front of the latter, and near the entrance, was a coffer or ark in which two small slabs of marble were deposited, twelve and one-half inches long by eight wide, on which the Assyrian King Assur-nazir-pal in a duplicate text records his erection of the sanctuary. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The temple sometimes enclosed a Bit-ili or Beth-el. This was originally an upright stone, consecrated by oil and believed to be animated by the divine spirit. The “Black Stone” in the kaaba of the temple of Mecca is a still surviving example of the veneration paid by the Semitic nations to sacred stones. Whether, however, the Beth-els of later Babylonian days were like the “Black Stone” of Mecca, really the consecrated stones which had once served as temples, we do not know; in any case they were anchored within the walls of the temples which had taken their place as the seats of the worship of the gods.

Offerings were still made to them in the age of Nebuchadnezzar and his successors; thus we hear of 765 “measures” of grain which were paid as “dues to the Beth-el” by the serfs of one of the Babylonian temples. The “measure,” it may be stated, was an old measure of capacity, retained among the peasantry, and only approximately exact. It was calculated to contain from 41 to 43 qas.

Important Temples in Mesopotamia

Nippur was one of the oldest temples. It was built in honor of Mul-lil or Enlil, “the lord of the ghost- world.” He had originally been the spirit of the earth and the underground world; when he became a god his old attributes still clung to him. To the last he was the ruler of the lil-mes, “the ghosts” and “demons” who dwelt in the air and the waste places of the earth, as well as in the abode of death and darkness that lay beneath it. His priests preserved their old Shamanistic character; the ritual they celebrated was one of spells and incantations, of magical rites and ceremonies. Nippur was the source and centre of one of the two great streams of religious thought and culture which influenced Sumerian Babylonia. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The other source and centre was Eridu on the Persian Gulf. Here the spirit of the water was worshipped, who in process of time passed into Ea, the god of the deep. But the deep was a channel for foreign culture and foreign ideas. Maritime trade brought the natives of Eridu into contact with the populations of other lands, and introduced new religious conceptions which intermingled with those of the Sumerians. Ea, the patron deity of Eridu, became the god of culture and light, who delighted in doing good to mankind and in bestowing upon them the gifts of civilization. In this he was aided by his son Asari, who was at once the interpreter of his will and the healer of men. His office was declared in the title that was given to him of the god “who benefits mankind.”

See Separate Article: NIPPUR: THE RELIGIOUS CENTER OF MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Herodotus on the Great Temple in Babylon

Herodotus wrote in “The History of the Persian Wars” ( c. 430 B.C.): “In the one stood the palace of the kings, surrounded by a wall of great strength and size: in the other was the sacred precinct of Jupiter Belus [Bel], a square enclosure two furlongs each way, with gates of solid brass; which was also remaining in my time. In the middle of the precinct there was a tower of solid masonry, a furlong in length and breadth, upon which was raised a second tower, and on that a third, and so on up to eight. The ascent to the top is on the outside, by a path which winds round all the towers. [Source: Herodotus, “The History”, translated by George Rawlinson, (New York: Dutton & Co., 1862]

“When one is about half-way up, one finds a resting-place and seats, where persons are wont to sit some time on their way to the summit. On the topmost tower there is a spacious temple, and inside the temple stands a couch of unusual size, richly adorned, with a golden table by its side. There is no statue of any kind set up in the place, nor is the chamber occupied of nights by any one but a single native woman, who, as the Chaldaeans, the priests of this god, affirm, is chosen for himself by the deity out of all the women of the land. I.182: They also declare — but I for my part do not credit it — that the god comes down in person into this chamber, and sleeps upon the couch. This is like the story told by the Egyptians of what takes place in their city of Thebes, where a woman always passes the night in the temple of the Theban Jupiter [Amon-Ra].

“In each case the woman is said to be debarred all intercourse with men. It is also like the custom of Patara, in Lycia, where the priestess who delivers the oracles, during the time that she is so employed — for at Patara there is not always an oracle — is shut up in the temple every night.I.183: Below, in the same precinct, there is a second temple, in which is a sitting figure of Jupiter [Marduk], all of gold. Before the figure stands a large golden table, and the throne whereon it sits, and the base on which the throne is placed, are likewise of gold.

Babylon

“The Chaldaeans told me that all the gold together was eight hundred talents' weight. Outside the temple are two altars, one of solid gold, on which it is only lawful to offer sucklings; the other a common altar, but of great size, on which the full-grown animals are sacrificed. It is also on the great altar that the Chaldaeans burn the frankincense, which is offered to the amount of a thousand talents' weight, every year, at the festival of the God. In the time of Cyrus there was likewise in this temple a figure of a man, twelve cubits high, entirely of solid gold. I myself did not see this figure, but I relate what the Chaldaeans report concerning it. Darius, the son of Hystaspes, plotted to carry the statue off, but had not the hardihood to lay his hands upon it. Xerxes, however, the son of Darius, killed the priest who forbade him to move the statue, and took it away. Besides the ornaments which I have mentioned, there are a large number of private offerings in this holy precinct.” I.184:

Purpose of Temples in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: “The modem and occidental view of a temple as a place of worship gives only a part of the picture when we come to regard the sanctuaries of the gods in Babylonia and Assyria. Throughout antiquity, the sanctuary represents, first and foremost, the dwelling of a god. Among the Semites it grows up around the sacred stone, which, originally the god himself, becomes either, in the form of an altar, a symbol of his presence, or is given the outlines of an animal or human figure (or a combination of the two), and becomes a representative of the deity—his counterfeit. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“The charming legend of Jacob’s dream, devised to account for the sanctity of an ancient centre of worship—Luz,—illustrates this development of the temple, from an ancient and more particularly from a Semitic point of view. The “place” to which Jacob comes is a sacred enclosure formed by stones. His stone pillow is the symbol of the deity, and originally the very deity himself. The god in the stone “reveals” himself, because Jacob by direct contact with the stone becomes, as it were, one with the god, precisely as a sacred relic—an image, or any sacred symbol— communicates a degree of sanctity to him who touches it, whether by kissing it or by pressing against it. When Jacob awakes he realises that Jahweh is the god of the sacred enclosure, which he designates as “the house of the Lord” (Elohim) and “gate of heaven.” He sets up the stone as an altar, anoints it (thus doing homage to the deity represented by the stone,) precisely as one anoints a king or a priest. He changes the name of the sacred place to Bethel, i.e., “house of God,” and declares his intention on his return to his father’s house to convert the stone into a “house of the Lord.” The stone becomes the house, and the sanctuary is the home of the god represented by the stone.

Temples Organization in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: “With the growth of the temple organisation, its administration also assumed large proportions. The functions of the priests were differentiated, and assigned to several classes—diviners, exorcisers, astrologers, physicians, scribes, and judges of the court, to name only the more important; and as early as the days of Hammurabi, we learn of priestesses attached to the service of Shamash and of other gods. The importance of these priestesses, however, appears to have grown less, as the religion developed. An institution like that of the vestal virgins also existed at an early period, though the material at our disposal is as yet too meagre to enable us to specify the nature of the institution, or the share in the cult allotted to these virgins. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“The temple was also the centre of intellectual life. Within the sacred precinct was the temple school in which the aspirants to the priesthood were prepared for their future careers—just as to this day the instruction of the young in Islamism, as well as the discussions of the learned, takes place within the precincts of the mosques. Learning remained under the control of the priests throughout all periods of Babylonian and Assyrian history. In a certain very definite sense all learning was religious in character, or touched religion at some vital point. In the oldest legal code of the Pentateuch, the so-called “Book of the Covenant,” the term used for the exercise of legal functions is “to draw nigh to the Lord” (Elohim), i.e., to appear before God, and this admirably reflects the legal procedure in Babylonia and Assyria. The laws of the country represented the decrees of the gods. Legal decisions were accordingly given through the representatives and servitors of the gods—the kings, in the earlier ages, and later the priests.

“At the close of his famous code, Hammurabi, whose proudest title is that of “king of righteousness,” endowed with justice by Shamash—the paramount god of justice and righteousness,—states that one of the aims of his life was to restrain the strong from oppressing the weak, and to procure justice for the orphan and the widow. He appropriately deposits in E-Sagila, the temple of Marduk in Babylon, the stone on which he had inscribed the laws of the country “for rendering decisions, for decreeing judgments in the land, for the righting of wrongs.” The ultimate source of all law being the deity himself, the original legal tribunal was the place where the image or symbol of the god stood. A legal decision was an oracle or omen, indicative of the will of the god. The Hebrew word for law, toralfi , has its equivalent in the Babylonian ter tu, which is the common term for “omen.” This indissoluble bond between law and religion was symbolised by retaining the tribunal, at all times, within the temple area and by placing the dispensing of justice in the hands of the priests—a condition that is also characteristic of legal procedure in all the Pentateuchal codes, including the latest, the so-called Priestly Code.

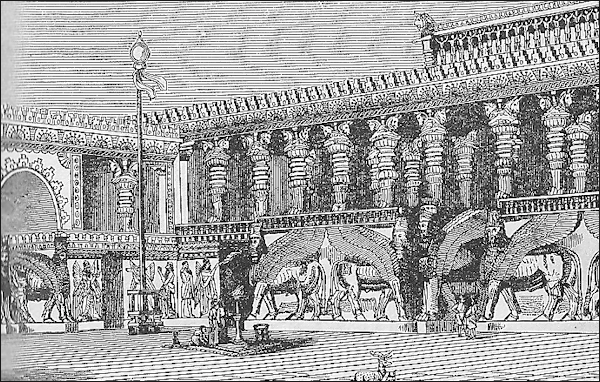

Sargon's Palace at Khorsabad

Temple Power in Mesopotamia

Claude Hermann and Walter Johns wrote in the Encyclopedia Britannica: “The temple occupied a most important position. It received from its estates, from tithes and other fixed dues, as well as from the sacrifices (a customary share) and other offerings of the faithful, vast amounts of all sorts of naturalia; besides money and permanent gifts. The larger temples had many officials and servants. Originally, perhaps, each town clustered round one temple, and each head of a family had a right to minister there and share its receipts. [Source: Claude Hermann Walter Johns, Babylonian Law — The Code of Hammurabi. Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911]

“As the city grew, the right to so many days a year at one or other shrine (or its "gate") descended in certain families and became a species of property which could be pledged, rented or shared within the family, but not alienated. In spite of all these demands, however, the temples became great granaries and store-houses; as they also were the city archives. The temple held its responsibilities. If a citizen was captured by the enemy and could not ransom himself the temple of his city must do so. To the temple came the poor farmer to borrow seed corn or supplies for harvesters, etc. — advances which he repaid without interest. The king's power over the temple was not proprietary but administrative. He might borrow from it but repaid like other borrowers. The tithe seems to have been the composition for the rent due to the god for his land. It is not clear that all lands paid tithe, perhaps only such as once had a special connexion with the temple.”

Morris Jastrow said: “ Even in the purely business activity of the country, the bond between culture and religion is exemplified by the large share taken by the temples in the commercial life. The temples had large holdings in land and cattle. They loaned money and engaged in mercantile pursuits of various kinds; so that a considerable portion of the business documents in both the older and the later periods deal with temple affairs, and form part of the official archives of the temples. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

Priests in Mesopotamia

Sumerian high priests were believed to be mouthpieces of the gods. They presided over rituals and often divined the future by reading the entrails of sheep or goats. Hammurabi Code of the Babylonians addresses a class of persons devoted to the service of a god, as vestals or hierodules. The vestals were vowed to chastity, lived together in a great nunnery, were forbidden to open or enter a tavern, and together with other votaries had many privileges.

Temple priests and priestess lived in apartment in the temple. The sex of the overseer was usually opposite that of the major deity in the temple. Under the main priest or priestess was of courtier of minor priests, each of whom performed a different task at the temple such as sacrificing, anointing or pouring libations. Quarters for sacred prostitutes, temple slaves and eunuchs were placed around the temple. ["World Religions" edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Morris Jastrow said: “The power thus lodged in the priests of Babylonia and Assyria was enormous. They virtually held in their hands the life and death of the people, and while the respect for authority, the foundation of all government, was profoundly increased by committing the functions of the judges to the servitors of the gods, yet the theory upon which the dispensation of justice rested, though a logical outcome of the prevailing religious beliefs, was fraught with grave dangers. A single unjust decision was sufficient to shake the confidence not merely in the judge but in the god whose mouthpiece he was supposed to be. An error on the part of a judge demonstrated, at all events, that the god no longer cherished him; he had forfeited the god’s assistance. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“Accordingly, one of the first provisions in the Hammurabi code ordains that a judge who renders a false decision is to be removed from office. There was no court of appeal in those days; nor any need of one, under the prevailing acceptance of legal decisions. The existence of this provision may be taken as an indication that the incident was not infrequent. On the other hand, the thousands of legal documents that we now have from almost all periods of Babylonian-Assyrian history furnish eloquent testimony to the scrupulous care with which the priests, as judges, sifted the evidence brought before them, and rendered their decisions in accordance with this evidence.”

Babylonian priests were distinguished by a curiously flounced dress, made perhaps of a species of muslin, which descended to the feet, and is often pictured on the early seals. Over their shoulders was flung a goat's skin, the symbol of their office, like the leopard's skin worn by the priests in Egypt. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Assyrian Palace

Priest Hierarchy and Temple Servants

The hierarchy of priests was large. At its head was the patesi, or high- priest, who in the early days of Babylonian history was a civil as well as an ecclesiastical ruler. He lost his temporal power with the rise of the kings. But at first the King was also a patesi, and it is probable that in many cases at least it was the high-priest who made himself a king by subjecting to his authority the patesis or priestly rulers of other states. In Assyria the change of the high-priest into a king was accompanied by revolt from the supremacy of Babylonia. With the establishment of a monarchy the high-priest lost more and more his old power and attributes, and tended to disappear altogether, or to become merely the vicegerent or representative of the King. The King himself, mindful of his sacerdotal origin, still claimed semi-priestly powers. But he now called himself a sangu or “chief priest” rather than a patesi; in fact, the latter name was retained only from antiquarian motives. The individual high-priest passed away, and was succeeded by the class of “chief priests.”Under them were several subordinate classes of temple servants. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Under them were several subordinate classes of temple servants. There were, for instance, the enû, or “elders,” and the pasisû, or “anointers,” whose duty it was to anoint the images of the gods and the sacred vessels of the temple with oil, and who are sometimes included among the ramkû, or “offerers of libations,” as well. By the side of them stood asipu, or “prophet,” who interpreted the will of heaven, and even accompanied the army on its march, deciding when it might attack the enemy with success, or when the gods refused to grant it victory. Next to the prophet came the makhkhû or interpreter of dreams, as well as the barû, or “seer.” A very important class of temple-servants were the kalî, or “eunuch- priests,” the galli of the religions of Asia Minor. They were under a “chief kalû,” and were sometimes entitled “the servants of Ishtar.” It was indeed to her worship that they were specially consecrated, like the ukhâtu and kharimâtu, or female hierodules. Erech, with its sanctuary of Anu and Ishtar, was the place where these latter were chiefly to be found; here they performed their dances in honor of the goddess and mourned over the death of Tammuz.

Closely connected with the kalî was a sort of monastic institution, which seems to have been attached to some of the Babylonian temples. The Zikari, who belonged to it, were forbidden to marry, and it is possible that they were eunuchs like the kalî. They, too, were under a chief or president, and their main duty was to attend to the daily sacrifice and to minister to the higher order of priests. In this respect they resembled the Levites at Jerusalem; indeed they are frequently termed “servants” in the inscriptions, though they were neither serfs nor slaves. They could be dedicated to the service of the Sun-god from childhood. A parallel to the dedication of Samuel is to be found in a deed dated at Sippara on the 21st of Nisan, in the fifth year of Cambyses, in which “Ummu-dhabat, the daughter of Nebo-bel-uzur,” whose father-in-law was the priest of the Sun-god, is stated to have brought her three sons to him, and to have made the following declaration before another priest of the same deity: “My sons have not yet entered the House of the Males (Zikari); I have hitherto lived with them; I have grown old with them since they were little, until they have been counted among men.” Then she took them into the “House of the Males” and “gave” them to the service of the god.

We learn from this and other documents that the Zikari lived together in a monastery or college within the walls of the temple, and that monthly rations of food were allotted to them from the temple revenues. The ordinary priests were married, though the wife of a priest was not herself a priestess. There were priestesses, however, as well as female recluses, who, like the Zikari, were not allowed to marry and were devoted to the service of the Sun-god. They lived in the temple, but were able to hold property of their own, and even to carry on business with it. A portion of the profits, nevertheless, went to the treasury of the temple, out of whose revenues they were themselves supplied with food. From contracts of the time of Khammurabi we gather that many of them not only belonged to the leading families of Babylonia, but that they might be relations of the King.

Temple Women in Mesopotamia

From the earliest period, moreover, there were women who lived like nuns, unmarried and devoted to the service of the Sungod. The office was held in high honor, one of the daughters of King Ammi-Zadok, the fourth successor of Khammurabi or Amraphel, being a devotee of the god. In the reign of the same king we find two of these devotees and their nieces letting for a year nine feddans or acres of ground in the district in which the “Amorites” of Canaan were settled. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

This was done “by command of the high-priest Sar-ilu,” a name in which Pinches suggests that we should see that of Israel. The women were to receive a shekel of silver, or three shillings, “the produce of the field,” by way of rent, while six measures of corn on every ten feddans were to be set apart for the Sun-god himself. In the previous reign a house had been let at an annual rent of two shekels which was the joint property of a devotee of the Sun-god Samas and her brother. It is clear that consecration to the service of the deity did not prevent the “nun” from owning and enjoying property.

Temple women were not supposed to have children, yet they could and often did marry. The Code contemplated that such a wife would give a husband a maid as above. Free women might marry slaves and be dowered for the marriage. The children were free, and at the slave's death the wife took her dowry and half what she and her husband had acquired in wedlock for self and children; the master taking the other half as his slave's heir.” [Source: Claude Hermann Walter Johns, Babylonian Law — The Code of Hammurabi. Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911 ]

Wholly distinct from these devotees of the Sun-god were the female hierodules or prostitutes of Ishtar, to whom reference has already been made. Distinct from them, again, were the prophetesses of Ishtar, who prophesied the future and interpreted the oracles of the goddess. One of their chief seats was the temple of Ishtar at Arbela, and a collection of the oracles delivered by them and their brother prophets to Esar-haddon has been preserved. It is thus that he is addressed in one of them: “Fear not, O Esar-haddon; the breath of inspiration which speaks to thee is spoken by me, and I conceal it not. Thine enemies shall melt away from before thy feet like the floods in Sivan. I am the mighty mistress, Ishtar of Arbela, who have put thine enemies to flight before thy feet. Where are the words which I speak unto thee, that thou hast not believed them? I am Ishtar of Arbela; thine enemies, the Ukkians, do I give unto thee. I am Ishtar of Arbela; in front of thee and at thy side do I march. Fear not, thou art in the midst of those that can heal thee; I am in the midst of thy host. I advance and I stand still!” It is probable that these prophetesses were not ordained to their office, but that it depended on their possession of the “spirit of inspiration.” At all events, we find men as well as women acting as the mouth-pieces of Ishtar, and in one instance the woman describes herself as a native of a neighboring village “in the mountains.”

Temple Fees and Expenses

The revenues of the temples and priesthood were derived partly from endowments, partly from compulsory or voluntary offerings. Among the compulsory offerings were the esrâ, or “tithes.” These had to be paid by all classes of the population from the King downward, either in grain or in its equivalent in money. The “tithe” of Nabonidos, immediately after his accession, to the temple of the Sun-god at Sippara was as much as 5 manehs of gold, or £840. We may infer from this that it was paid on the amount of cash which he had found in the treasury of the palace and which was regarded as the private property of the King. Nine years later Belshazzar, the heir-apparent, offered two oxen and thirty-two sheep as a voluntary gift to the same temple, and at the beginning of the following year we find him paying a shekel and a quarter for a boat to convey three oxen and twenty-four sheep to the same sanctuary. Even at the moment when Cyrus was successfully invading the dominions of his father and Babylon had already been occupied for three weeks by the Persian army, Belshazzar was careful to pay the tithe due from his sister, and amounting to 47 shekels of silver, into the treasury of the Sun-god. As Sippara was in the hands of the enemy, and the Babylonian forces which Belshazzar commanded had been defeated and dispersed, the fact is very significant, and proves how thoroughly both invaders and invaded must have recognized the rights of the priesthood. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Tithe was also indirectly paid by the temple-serfs. Thus in the first year of Nergal-sharezer, out of 3,100 measures of grain, delivered by “the serfs of the Sun-god” to his temple at Sippara, 250 were exacted as “tithe.” These serfs must be distinguished from the temple-slaves. They were attached to the soil, and could not be separated from it. When, therefore, a piece of land came into the possession of a temple by gift and endowment, they went along with it, but their actual persons could not be sold. The slave, on the other hand, was as much a chattel as the furniture of the temple, which could be bought and sold; he was usually a captive taken in war, more rarely a native who had been sold for debt. All the menial work of the temple was performed by him; the cultivation of the temple-lands, on the contrary, was left to the serfs. It is doubtful whether the “butchers,” or slaughterers of the animals required for sacrifice, or the “bakers” of the sacred cakes, were slaves or freemen.

The expression used in regard to them in the contract of IzkurMerodach quoted above is open to two interpretations, but it would naturally signify that they were regarded as slaves. We know, at all events, that many of the artisans employed in weaving curtains for the temples and clothing for the images of the gods belonged to the servile class, and the gorgeousness of the clothing and the frequency with which it was changed must have necessitated a large number of workmen. Many of the documents which have been bequeathed to us by the archives of the temple of the Sun-god at Sippara relate to the robes and head-dresses and other portions of the clothing of the images which stood there. A considerable part of the property of a temple was in land. Sometimes this was managed by the priests themselves; sometimes its revenues were farmed, usually by a member of the priestly corporation; at other times it was let to wealthy “tenants.” One of these, Nebo-sum-yukin by name, who was an official in the temple of Nebo at Borsippa, married his daughter Gigîtum to Nergal-sharezer in the first year of the latter's reign.

Temples in Mesopotamia as Law and Business Centers

Morris Jastrow said: “The temples were the natural depositories of the legal archives, which in the course of centuries grew to veritably enormous proportions. Records were made of all decisions; the facts were set forth, and duly attested by witnesses. Business and marriage contracts, loans and deeds of sale were in like manner drawn up in the presence of official scribes, who were also priests. In this way all commercial transactions received the written sanction of the religious organisation. The temples themselves—at least in the large centres—entered into business relations with the populace. In order to maintain the large household represented by such an organisation as that of the temple of Enlil at Nippur, that of Ningirsu at Lagash, that of Marduk at Babylon, or that of Shamash at Sippar, large holdings of land were required which, cultivated by agents for the priests, or farmed out with stipulations for a goodly share of the produce, secured an income for the maintenance of the temple officials. The enterprise of the temples was expanded to the furnishing of loans at interest—in later periods, at 20 percent— to barter in slaves, to dealings in lands, besides engaging labour for work of all kinds directly needed for the temples. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

Wall relief depicting Ashur at Nimrud

“A large quantity of the business documents found in the temple archives are concerned with the business affairs of the temple, and we are justified in including the temples in the large centres as among the most important business institutions of the country. In financial or monetary transactions the position of the temples was not unlike that of national banks; they carried on their business with all the added weight of official authority. The legal and business functions thus attached to the temple organisations enlarged also the scope of the training given in the temple-schools. To instruction in methods of divination, in the rituals connected with exorcising demons and in other forms of incantations, in sacrificial and atonement rituals, in astrology, and in the treatment of diseases as supplementary to incantation rites, there was added training in the drawing up of legal documents, in the study of the laws, and in accounting, including calculations of interest and the like.

“It is to the temple-schools that we owe the intellectual activity of Babylonia and Assyria. The incentive to gather collections of omens, of incantations, and, of medical compilations, came from these schools. Though the motive was purely practical, viz., to furnish handbooks for the priests and to train young candidates for the priesthood, nevertheless the incentive was intellectual both in character and scope, and necessarily resulted in raising the standard of the priesthood and in stimulating the literary spirit. The popular myths and legends were given a literary form, and preserved in the archives of the temple- schools. An interest in fables was aroused, and the wisdom of the past preserved for future generations. Texts of various kinds were prepared for the schools. Hymns, rituals, incantations, omens, and medical treatises were edited and provided with commentaries or with glasses, and explanatory amplifications, to serve as text-books for the pupils and as guides for the teachers. For the study of the language, lists of signs with their values as phonetic symbols, and their meanings when used as ideographs were prepared. Lists of all kinds of objects were drawn up, names of countries and rivers, tables of verbal forms, with all kinds of practical exercises in combining nouns and verbs, and in forming little sentences.

“The practical purpose served by many of these exercises is shown by the character of the words and phrases chosen—they are such as occur in legal documents, or in omens, or in other species of religious texts used in the cult. Many of these school texts, including the collections of omens and incantations as well as hymns and rituals, were originally written in a “Sumerian” version, though emanating from priests who spoke Babylonian. It was found necessary to translate, or to “transliterate,” them into the Semitic Babylonian. We thus obtain many bilingual texts furnishing both the Semitic and the Sumerian versions. A large proportion of the literary texts in Ashurbana-pal’s library thus turn out to be school texts, and since we know that the scribes of Ashurbanapal prepared their copies from originals produced in Babylonia,—though Assyria also contributed her share towards literary productions,—the conclusion seems justified that it was through the temple-schools and for the temple-schools that the literature, which is almost wholly religious in character, or touches religion at some point, was produced.

“It will be apparent, therefore, that the temples of Babylonia and Assyria served a variety of purposes, besides being merely places of worship. They formed —to emphasise the point once more—the large religious households of the country, harbouring large bodies of priests for whose sustenance provision had to be made, superintending all the details of the administration of large holdings, exercising the functions of legal courts, acting as the depositories of official records—legal and historical,—besides engaging in the activities of business corporations and of training institutions in all the branches of intellectual activity that centred around the religious beliefs and the cult. It was through the temples, in short, that the bond between culture and religion, which was set forth in a previous lecture, was maintained during all periods of Babylonian and Assyrian history.

Temple Cults in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: “It is now incumbent on us to turn to the cult fostered at these sanctuaries in the south and the north. At the outset of this discussion it must be acknowledged that many of the details are still lost. We have, to be sure, in the library of Ashurbanapal the material for a reconstruction of the cult at the great centres, through the collection which this king made of hymns and incantations, omens and rituals, that formed part of the temple archives and of the equipment of the temple-schools at Nippur, Ur, Sippar, Babylon, Borsippa, Cuthah, Uruk, and no doubt, at many other places, though the bulk of the material appears to have come from two temples, E-Sagila at Babylon and E-Zida in Borsippa. This material is, however, in an almost bewildering state of confusion, and many investigations of special features will have to be made before it can be arranged in such a manner as to give a connected picture of the general cult. Fortunately, we have also, as supplementary to this material, original texts, belonging to the oldest period,—chiefly hymns, litanies, and lamentations,— which written in Sumerian, have recently been carefully studied and are now pretty well understood. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“The omen texts, including the omens of liver divinations, the astrological collections, and the miscellaneous classes of omens, may be excluded from the cult proper. Interpretations of omens, at all events, do not form an integral part of the official cult at the temples, despite the fact that they are concerned chiefly with public affairs or with those of the royal households, which, as repeatedly emphasised, have an official or semi-official rather than a personal character. They might be designated as religious rites, subsidiary to the official cult. In connection with the inspection of the liver of the sacrificial animal there was an invocation to Shamash, or to Shamash and Adad, combined; we have specimens of such appeals, dating from Assyrian days, in which the sun-god is invoked to answer questions through the medium of trustworthy omens, and implored to prevent any error in the rites about to be performed which would naturally vitiate them. There were, however, no fixed occasions for the consultations of livers. Whenever any necessity arose, as before a battle or previous to some important public undertaking, or in case of illness or some accident to the king or to a member of his immediate household, hepatoscopy was employed to determine the attitude of the gods toward the land or toward the royal household. Similarly, as we have seen, the observation of the heavenly bodies formed the perpetual concern of the bdru priests. Astrological reports were frequently sent to the rulers, always at new-moon and full-moon, and in the case of eclipse or obscurations of the moon’s or sun’s surface from any cause whatsoever.

“In cases where the signs of the heavens portended evil, expiatory rites were prescribed, and these being conducted in the temples, no doubt formed part of the official expiatory ritual. The ritual on these occasions is, however, independent of the observation of the heavenly bodies, and follows as an attachment to the omens derived from the observation. Finally, the miscellaneous collections of omens, are merely to be regarded as handbooks to guide the bdru priests in answering questions that might be put to them concerning any unusual or striking appearance among men or animals, or in nature in general. Every unusual happening being regarded as a sign from some god or goddess, it became the priest’s business to determine its import. Although he did this in his official capacity, the act of securing and furnishing the interpretation formed no part of the ritual; and the omens, even in these instances, frequently bore on the public welfare rather than on the fate or fortune of the individual. Such interpellations and decisions might be compared to the inquiries regarding ritualistic observances put to the Jewish Rabbis from Talmudic times down to our days in orthodox circles, which gave rise to an extensive branch of Rabbinical literature technically known as “Questions and Answers.”

“An intermediate position between the official and the extra-official cult is held by the incantation formulas, and the observances connected therewith. In this branch of religious literature the layman received a large share of attention—larger even than in the case of the miscellaneous omens dealing with occurrences in daily life. In so far as the incantations represent the practices supplementary to medicinal treatment to release individuals from the tortures of the demons, or from the control of the sorcerers, they partake of the nature of private rites, which, although observed under the guidance and superintendence of priests, can be regarded only in a limited sense as forming part of the official cult.

Part of the Inanna Temple at Uruk

Temple Hymn

One temple hymn reads: “1-7 O E-unir (House which is a ziqqurat), grown together with heaven and earth, foundation of heaven and earth, great banqueting hall of Eridu! Abzu, shrine erected for its prince, E-dul-kug (House which is the holy mound) where pure food is eaten, watered by the prince's pure canal, mountain, pure place cleansed with the potash plant, abzu, your tigi drums belong to the divine powers.[Source: J.A. Black, G. Cunningham, E. Robson, and G. Zlyomi 1998, 1999, 2000, Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford University, Babylonia Index, piney.com]

“8-15 Your great ...... wall is in good repair. Light does not enter your meeting-place where the god dwells, the great assembly-room, the assembly-room, the beautiful place. Your tightly constructed house is sacred and has no equal. Your prince, the great prince, has fixed firmly a holy crown for you in your precinct – O Eridu with a crown placed on your head, bringing forth thriving thornbushes, pure thornbushes for the susbu priests , O Ec-abzu (Shrine which is the abzu), your place, your great place!

“16-23 At your place of calling upon Utu, at your oven bringing bread to eat, on your ziqqurat (Tower of Babel), a magnificent shrine stretching toward heaven, at your great oven rivalling the great banqueting hall, your prince, the prince of heaven and earth ...... can never be changed, the ......, the creator, the ......, the wise one, the ......, lord Nudimmud, has erected a house in your precinct, O E-engura (House of the subterranean waters), and taken his seat upon your dais.

24 (23 lines: the house of Enki in Eridu.) -37 O ......, shrine where destiny is determined, ......, foundation, raised with a ziqqurat, ......, settlement of Enlil, your ......,your right and your left are Sumer and Akkad. House of Enlil, your interior is cool, your exterior determines destiny. Your door-jambs and architrave are a high mountain, your projecting pilasters a dignified mountain. Your peak is a ...... peak of your princely platform. Your base serves heaven and earth. Your prince, the great prince Enlil, the good lord, the lord of the limits of heaven, the lord who determines destiny, the Great Mountain Enlil, has erected a house in your precinct, O shrine Nibru, and taken his seat upon your dais.

“39-46 O Tummal, exceedingly worthy of the princely divine powers, inspiring awe and dread! Foundation, your pure lustration extends over the abzu. Primeval city, reed-bed green with old reeds and new shoots, your interior is a mountain of abundance built in plenitude. At your feast held in the month of the New Year, you are wondrously adorned as the great lady of Ki-ur rivals Enlil. Your princess, mother Ninlil, the beloved wife of Nunamnir, has erected a house in your precinct, O E-Tummal (Tummal House), and taken a place upon your dais.

“48-56 O E-melem-huc (House of terrifying radiance) exuding great awesomeness, Ec-mah (Magnificent shrine), to which princely divine powers were sent from heaven, storehouse of Enlil founded for the primeval divine powers, worthy of nobility, lifting your head in princeship, counsellor of E-kur, pillar of the surroundings, your house ...... the platform with heaven. The decisions at its place of reaching the great judgment — the river of the ordeal — let the just live and consign to darkness the hearts that are evil. In your great place fit for pure lustration and the rites of icib priests, you dine with lord Nunamnir...

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024