Home | Category: Babylonians and Their Contemporaries

OLD BABYLONIANS

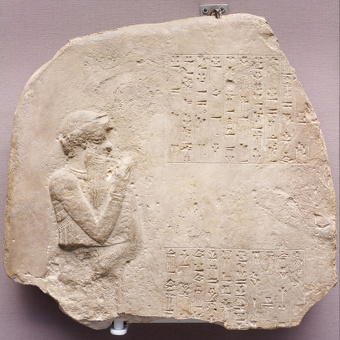

Hammurabi bas-relief at the

U.S. House of Representatives Babylonians were people that lived in Babylonia. They were a mixture of different peoples with different origins. Babylonia is an ancient state in Mesopotamia between the Tigris and the Euphrates Rivers; corresponding approximately to modern Iraq. Babylonia is the Greek form of the name babili — sometimes translated as "gate of God" — known from cuneiform texts. The city of Babylon was the main city and capital of Babylonia. The

The Babylonians ruled Mesopotamia from 1792 to 1595 B.C. They are sometimes called the Old Babylonians to distinguish them from the Neo-Babylonians (792 to 595 B.C.) who defeated the Assyrians and established a large empire. The empire reached its peak in the 6th century B.C. under Nebuchadnezzar, the famous Biblical ruler. The Neo-Babylonians are also known by their Biblical name the Chaldeans. Sometimes their state is called the Second Babylonian Empire.

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: For most of the third millennium B.C., Babylon was just one of many Sumerian city-states that flourished in southern Mesopotamia. Older cities such as Ur, whose patron deity was the moon god, Nanna — later known as Sin — were much more powerful. Around 2000 B.C., Babylon began to acquire a reputation as a religious center and place of scholarship. By then its residents spoke Akkadian, a Semitic language that had replaced Sumerian as the lingua franca of Mesopotamia. During this period, after the rise of what scholars today call the Old Babylonian Dynasty and the ascension of rulers such as Hammurabi (r. ca. 1810–1750 B.C.), Babylon became the region’s most influential city. Previously a minor storm god, Marduk became its patron and was gradually elevated to his position as one of the most powerful deities in the Mesopotamian pantheon. Throughout the second and early first millennia B.C., Babylon’s status as Mesopotamia’s leading city waxed and waned. Although it was sometimes seized by foreigners, these outsiders always eventually adopted Babylonian culture, becoming indistinguishable from the city’s Akkadian-speaking citizens. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, March/April 2022]

The Old Babylonians developed commerce, legal codes, astrology and science and built great temples Babylonian religion and art was based on that of the Sumerians. They are credited with discovering mathematical principals such as trigonometry and prime, square and cube numbers — concepts further developed by the ancient Greeks more than 1,000 years later.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RELATED ARTICLES:

BABYLON AND BABYLONIA: GEOGRAPHY AND OCCUPIERS africame.factsanddetails.com

OLD BABYLONIANS: THEIR HISTORY, ACHIEVEMENTS, RISE AND FALL africame.factsanddetails.com ;

BABYLON GOVERNMENT: RULERS, LAWS, HAMMURABI africame.factsanddetails.com ;

OLD BABYLON AND THE BIBLE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

BABYLONIAN LIFE, RELIGION AND CULTURE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

RIVALS AND CONTEMPORARIES OF THE BABYLONIANS: ELAM, EMAR, MASHKAN africame.factsanddetails.com ;

EBLA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUCCESSORS OF THE BABYLONIANS: MITANNI, HURRIANS, QATNA AND KASSITES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A History of Babylon (2200 BC - AD 75" by Paul-Alain Beaulieu (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

“Babylonia: A Very Short Introduction” by Trevor R. Bryce (2016) Amazon.com;

“Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization” by Paul Kriwaczek (2010) Amazon.com;

“Babylonia” by Costanza Casati (2025) Novel Amazon.com;

“Babylonians” by H. W. F. Saggs (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Greatness That Was Babylon” by H. W. F. Saggs (1962) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian Empire” by Enthralling History (2022) Amazon.com;

“The City of Babylon: A History, C. 2000 BC - AD 116" by Stephanie Dalley (2021) Amazon.com;

“The World Around the Old Testament: The People and Places of the Ancient Near East”

by Bill T. Arnold and Brent A. Strawn (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Amorites: The History and Legacy of the Nomads Who Conquered Mesopotamia and Established the Babylonian Empire” by Charles River Editors (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Amorite Kingdoms: The History of the First Babylonian Dynasty and the Other Mesopotamian Kingdoms Established by the Amorites” by Charles River Editors (2021) Amazon.com;

“The First Great Powers: Babylon and Assyria” by Arthur Cotterell (2019) Amazon.com;

“The History of Babylonia and Assyria” by Hugo Winckler (1892) Amazon.com;

“Civilizations of Ancient Iraq” by Benjamin R. Foster and Karen Polinger Foster ((2009) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Ancient Near East” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2003) Amazon.com;

“King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography” by Marc Van De Mieroop Amazon.com;

“Hammurabi of Babylon” by Dominique Charpin Amazon.com;

“The Code of Hammurabi” by Hammurabi Amazon.com;

“Babylonia, the Gulf Region, and the Indus: Archaeological and Textual Evidence for Contact in the Third and Early Second Millennium B.C.” by Piotr Steinkeller Amazon.com;

Babylonians — and Their Sumerian and Semitic Roots with Some Ammorite Thrown In

The Babylonians weren’t really a people like the Sumerians, Akkadians and Assyrians. They were more of a mongrel mix of people — like people in the United States — who lived in a particular place — Babylonia — under a particularly government. Babylonians adopted used the Sumerian language and script in their writing and documents. Babylonian names assume Sumerian forms. Their religion was essentially Sumerian too. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Semitic influences initially came from the Akkadians, who were a Semitic people who spoke a Semitic language and ruled Mesopotamia for around two centuries. It was from the Sumerian that Semites learnt to live in cities. Their own word for “city” was âlu, the Hebrew 'ohel “a tent,” which is still used in the Old Testament in the sense of “home;” the Hebrew 'îr is the Sumerian eri.Ekallu, the Hebrew hêkal, “a palace,” comes from the Sumerian ê-gal or “great house”.

Semites absorbed Sumerian culture. For centuries they lived in a mix with Sumerian people. The two peoples acted and re-acted on each other and a mixed people was the result, with a mixed language and a mixed form of religion. Members of the same family had names derived from different families of speech, and while the old Sumerian borrowed Semitic words which it spelt phonetically, the Semitic lexicon was enriched with loan-words from Sumerian which were treated like Semitic roots. The Semite improved upon the heritage he had received. Even the system of writing was enlarged and modified. Its completion and arrangement are due to Semitic scribes who had been trained in Sumerian literature. It was probably at the court of Sargon of Akkad that what we may term the final revision of the syllabary took place.

In Babylonia, Sumerians and the Semites become one people. But the mixture of nationalities in Babylonia was not yet complete. Colonies of Amorites, from Canaan, settled in it for the purposes of trade; wandering tribes of Semites, from Northern Arabia, pastured their cattle on the banks of its rivers, and in the Abrahamic age a line of kings from Southern Arabia made themselves masters of the country, and established their capital at Babylon. Their names resembled those of Southern Arabia on the one hand, of the Hebrews on the other, and the Babylonian scribes were forced to give translations of them in their own language. But all these incomers belonged to the Semitic race, and the languages they spoke were but varieties of the same family of speech.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia:"In treating of the history, character, and influence of this ancient empire, it is difficult not to speak at the same time of its sister, or rather daughter, country, Assyria. This northern neighbour and colony of Babylon remained to the last of the same race and language and of almost the same religion and civilization as that of the country from which it emigrated. The political fortunes of both countries for more than a thousand years were closely interwoven with one another; in fact, for many centuries they formed one political unit..” [Source: J.P. Arendzen, transcribed by Rev. Richard Giroux,Catholic Encyclopedia |=|]

Babylonian Language

Babylonians spoke Akkadian — an extinct East Semitic language that was spoken in ancient Mesopotamia in Akkad, Assyria, Isin, Larsa, Babylonia and perhaps Dilmun) from the third millennium B.C. until its gradual replacement in common use by Old Aramaic among Assyrians and Babylonians from the 8th century B.C. [Source: Wikipedia]

By the 10th century B.C. , there were two variant dialectic forms of Akkadian — Assyrian and Babylonian, spoken in Assyria and Babylonia respectively. Assyrian and Babylonian were the native language of the Mesopotamian empires (Old Assyrian Empire, Babylonia, Middle Assyrian Empire) and was lingua franca for much of the Ancient Near East in until the Bronze Age collapse around 1150 B.C. However, its gradual decline began in the Iron Age, during the Neo-Assyrian Empire when in the mid-eighth century B.C. Tiglath-Pileser III introduced Imperial Aramaic as a lingua franca of the Assyrian empire. By the Greek era the language was largely confined to scholars and priests working in temples in Assyria and Babylonia. The last known Akkadian cuneiform document dates from the A.D. 1st century.

Babylonians and Science

The Mesopotamians are credited with inventing mathematics. The Mesopotamians numerical system was based on multiples of 6 and 10. The first round of numbers were based on ten like ours, but the next round were based on multiples of six to get 60 and 600. Why it was based on multiples of six no one knows. Perhaps it is because the number 60 can be divided by many numbers: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 12, 15 , 20 and 30.

Babylonians devised the system of dividing a circle into 360 degrees (some say it was the Assyrians who first divided the circle). The tiny circle as a sign for a degree was probably originally a hieroglyph for the sun from ancient Egypt. A circle was used by the ancient Babylonian and Egyptian astronomers to the circle the zodiac. The degree was a way of dividing a circle and designating the distance traveled by the sun each day. It is no coincidence then that the number of degrees in a circle (360) corresponds with the days of the year on the Babylonian calendar.

The Babylonians are often given credit for devising the first calendars, and with them the first conception of time as an entity. They developed and used the 360-day year — divided into 12 lunar months of 30 days (real lunar months are 29½ days) — devised by the Sumerians and introduced the seven day week, corresponding to the four waning and waxing periods of the lunar cycle. The ancients Egyptians adopted the 12-month system to their calendar. The ancient Hindus, Chinese, and Egyptians, all used 365-day calendars.

The Babylonians stuck stubbornly to the lunar calendar to define the year even though 12 lunar months did not equal one year. In 432 B.C., the Greeks introduced the so-called Metonic cycle in which every 19 years seven of the years had thirteen months and 12 years had 12 months. These kept the seasons in synch with the year and the roughly kept the days and months of the Metonic year in synch with those on the lunar calendar. The Metonic calendar was too complicated for everyday use and used mostly by astronomers.

Marduk — Babylon's God King

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: In the third millennium B.C., Babylon was a small, obscure city. Marduk was a minor deity with equally obscure origins who seems to have been associated with agriculture and canals, and whose symbol was a spade. During this period, Nippur was Mesopotamia’s most sacred city, and its god, Enlil, wielded ultimate divine power. But in the second millennium B.C., especially during the reign of Hammurabi (r. ca. 1792–1750 B.C.), Marduk became an ever more consequential god. As Babylon’s influence grew, he assumed the powers and name of Addu, a storm god who was the patron deity of the city of Halab, modern-day Aleppo. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, March/April 2022]

Toward the end of his reign, Hammurabi defeated the ruler of the city of Eshnunna, which had been allied with the Elamite people who lived in modern-day Iran and posed a constant threat to Babylonia. At the same time, cuneiform texts celebrated Marduk’s victory over Eshnunna’s patron god Tishpak. Marduk then appropriated Tishpak’s chief symbol, the lion-dragon hybrid beast known as mušhuššu, or “furious snake,” with whom he would be associated for the rest of Babylonian history. Depictions of mušhuššu that decorated the city’s famed Ishtar Gate, which was built more than 1,000 years later, still commemorated Marduk’s victory over Tishpak, and Babylon’s over an important ally of Elam.

By the twelfth century B.C., Marduk played a central role in an updated Mesopotamian creation story known as the Enuma Elish, which later cuneiform tablets preserve in many versions. The standard account of this narrative legitimized the god’s position as ruler of the divine pantheon once headed by Enlil and explains how Babylon supplanted Nippur as Mesopotamia’s most important religious center. In the creation myth, Marduk is a young warrior god and the only deity willing to do combat with Tiamat, the goddess of the sea and embodiment of chaos. In return for facing Tiamat, the gods agree to make Marduk king of the gods. Upon killing the goddess, Marduk claims his throne and brings order to the cosmos and creates the world. He makes Babylon the first city and home to his Esagila temple, where Marduk lived in the form of his sacred statue. This version of the Enuma Elish completely ignores Enlil and his sacred city of Nippur, erasing Babylon’s rival from the creation story.

Babylon’s status as Mesoptomia’s chief city waxed and waned, and it was sometimes captured by outside powers, events Marduk’s followers needed to account for. One text known as the Marduk Prophecy recounts how Babylonians sometimes angered the god. Their city was consequently then seized by enemies such as the Hittites from Anatolia and Elamites, each of whom “godnapped” Marduk by capturing his sacred statue and taking it back to their respective capitals. The prophecy refers to these events as the travels of Marduk, as if the god chose to be borne away to foreign lands. Those second millenium B.C. sojourns were brought to an end by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezar I (r. ca. 1125–1104 B.C.), during whose reign the Enuma Elish may have first been written down. The king sacked the Elamite city of Susa, reclaimed Marduk’s statue, and brought it back home to Babylon, once again establishing it as Mesopotamia’s capital of both earthly and cosmic rule.

First Babylonian Empire

Babylon city became a power during the time of Hammurabi (1792–1750 B.C.) when it extended its influence over most of southern Mesopotamia, as well as over parts of northern Mesopotamia. After about 2000 B.C., the Sumerian civilization mostly based in southern Mesopotamia led more or less directly to the Babylonian civilization further north. The area occupied by Babylonia was settled by the Sumerians in the third millennium B.C. Sargon I (24th century B.C.) founded the Akkadian dynasty, which dominated the area for 200 years. At a later period (c. 1850 B.C.) the Amorites (mar-tu, "people of the west") ruled over northern Babylonia. [Source: Willard Oxtoby; Jacob Neusner, Encyclopaedia Judaica, Encyclopedia.com]

Babylonian influence reached as far west as the central Mediterranean. In 2012 Italian archaeologists working at the sanctuary of Tas-Silg on Malta announced they had discovered an agate fragment with a Middle Babylonian cuneiform inscription dating to the thirteenth or fourteenth century B.C. According to Archaeology magazine: Found more than 1,500 miles from Mesopotamia, where cuneiform was used, it is the westernmost example of the script ever found. The fragment, which was originally part of a crescent-shaped votive object mounted on a pole or hung on a rope, mentions the religious center of Nippur, the moon god "Sin," and the names of at least five people. According to project director Alberto Cazzella, it's difficult to know how and when the artifact arrived in Malta. He believes it was probably plundered during a war, taken to Greece, and then perhaps traded between the Mycenaean Greeks and the Cypriot world, which at the time included Malta. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2012]

Rise of Babylon

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: With the beginning of the 18th century B.C., the political geography of the Asiatic Near East can for the first time be rendered with reasonable accuracy, and many previously blank spots filled in. This was a period of intense commercial and diplomatic activity, punctuated by military campaigns and sieges conducted at considerable distances from home. The fortuitous recovery of archives from many diverse sites reveals a host of geographic names, and many of these can be approximately located, or even identified with archaeological sites, with the help of occasional itineraries. Such itineraries were guides to travelers or, more often, records of their journeys or of campaigns, comparable to the "War of the four kings against the five" in Genesis 14, by marauding armies, and come closest to maps in the absence of any real cartography.[Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

No small-scale map can, of course, show all the minor vassal and petty states in all their complexity. Even the larger kingdoms and city-states add up to a bewildering number. However, certain patterns can be detected. The Syrian desert was populated by loosely organized tribal groupings still maintaining a largely nomadic way of life; the mountainous border regions beyond the Tigris and the Upper Euphrates were being organized under various non-Semitic peoples who came under varying degrees of Mesopotamian cultural influence; the "Fertile Crescent" itself (that is, the valley of the two rivers together with the eastern Mediterranean littoral) was firmly in the hands of urbanized Amorite rulers.

Within this great arc, the largest and most central position was occupied by the kingdom of Shamshi-Adad i (c. 1813–1783), and, at the turn of the century, his seemed the most commanding position. From his capital at Shubat-Enlil, he kept a close eye on his two sons, who ruled their provinces from Mari and Ekallâtum, respectively. The vast archives of *Mari have revealed the intricacies of administration, diplomacy, and warfare of the time as well as the highly personal character of Shamshi-Adad's rule. The crown prince at Ekallâtum, whom he held up to his younger brother as a model, had inherited much of the wealth of nearby Ashur, amassed in the profitable trade with Anatolia in the previous century. Nonetheless, it is misleading to call Shamshi-Adad's realm, as is sometimes done, the first Assyrian empire, for his empire was not based on Ashur, and the petty kingdom of Ashur that survived his death was in no sense an empire.

The main challenge came from the south. The way had been paved by the kingdoms of Warium and Larsa. Warium, with its capital at Eshnunna in the valley of the Diyala River, included the ancient center of the Akkadian empire (and perhaps even preserved its Sumerian name, Uri, in Akkadianized form), while Larsa controlled the ancient Sumerian cities. These two Amorite kingdoms had succeeded in subjecting most of the independent city-states of Sumer and Akkad, and thus turned the tide of particularism that had followed the collapse of the Ur iii empire. They directed their expansionist policies into separate spheres of influence: Eshnunna north and west into Assyria and upper Mesopotamia, Larsa eastward to the ancestral lands of its last dynasty in Emutbal and beyond that toward Elam. That they avoided an open clash was, however, due even more to the existence, between the two, of a relatively small state that nonetheless maintained its independence from both and was destined shortly to succeed and surpass them as well as Shamshi-Adad.

Amorite Dynasty of the First Babylonian Empire

The first great dynasty for which ancient Babylon is known was West-Semitic and is likely the Amorite Dynasty referred to in the Old Testament. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia:“ The Babylonians called it the dynasty of Babylon, for, though foreign in origin, it may have had its actual home in that city, which it gratefully and proudly remembered. It lasted for 296 years and saw the greatest glory of the old empire and perhaps the Golden Age of the Semitic race in the ancient world. The names of its monarchs are: Sumu-abi (15 years), Sumu-la-ilu (35), Zabin (14), Apil-Sin (18), Sin-muballit (30); Hammurabi (35), Samsu-iluna (35), Abishua (25), Ammi-titana (25), Ammizaduga (22), Samsu-titana (31). [Source: J.P. Arendzen, transcribed by Rev. Richard Giroux, Catholic Encyclopedia |=|]

“Under the first five kings Babylon was still only the mightiest amongst several rival cities, but the sixth king, Hammurabi, who succeeded in beating down all opposition, obtained absolute rule of Northern and Southern Babylonia and drove out the Elamite invaders. Babylonia henceforward formed but one state and was welded into one empire. They were apparently stormy days before the final triumph of Hammurabi. The second ruler strengthened his capital with large fortifications; the third ruler was apparently in danger of a native pretender or foreign rival called Immeru; only the fourth ruler was definitely styled King; while Hammurabi himself in the beginning of his reign acknowledged the suzerainty of Elam.

extent of the First Babylonian Empire at the start and end of Hammurabi of Babylon's reign (1792 BC – 1750 BC)

“Whereas the Assyrian kings loved to fill the boastful records of their reigns with ghastly descriptions of battle and war, so that we possess the minutest details of their military campaigns, the genius of Babylon, on the contrary, was one of peace, and culture, and progress. The building of temples, the adorning of cities, the digging of canals, the making of roads, the framing of laws was their pride; their records breathe, or affect to breathe, all serene tranquility; warlike exploits are but mentioned by the way, hence we have, even in the case of the two greatest Babylonian conquerors, Hammurabi and Nabuchodonosor II, but scanty information of their deeds of arms.

"I dug the canal Hammurabi, the blessing of men, which bringeth the water of the overflow unto the land of Sumer and Akkad. Its banks on both sides I made arable land; much seed I scattered upon it. Lasting water I provided for the land of Sumer and Akkad. The land of Sumer and Akkad, its separated peoples I united, with blessings and abundance I endowed them, in peaceful dwellings I made them to live" -- such is the style of Hammurabi. In what seems an ode on the king, engraved on his statue we find the words: "Hammurabi, the strong warrior, the destroyer of his foes, he is the hurricane of battle, sweeping the land of his foes, he brings opposition to naught, he puts an end to insurrection, he breaks the warrior as an image of clay." But chronological details are still in confusion. In a very fragmentary list of dates the 31st year of his reign is given as that of the land Emutbalu, which is usually taken as that of his victory over western Elam, and considered by many as that of his conquest of Larsa and its king, Rim-Sin, or Eri-Aku. If the Biblical Amraphel be Hammurabi we have in Gen., xiv, the record of an expedition of his to the Westland previous to the 31st year of his reign. Of Hammurabi's immediate successors we know nothing except that they reigned in peaceful prosperity. That trade prospered, and temples were built, is all we can say. |=|

Hammurabi Era of Babylon (1792–1750 B.C.)

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: The city of Babylon was a relative newcomer among the members of the old Sumero-Akkadian amphictyony, though later, to match its subsequent importance, it claimed a fictitious antiquity reaching back to antediluvian times. It was strategically located near the narrow waist of the Tigris-Euphrates valley where the two rivers come closest together and whence the capitals of successive Mesopotamian empires have ruled the civilized world from Kish and Akkad down to Ctesiphon and Baghdad. Throughout the 19th century, it was the seat of an independent dynasty which shared (or claimed) a common ancestry with Shamshi-Adad and whose rulers enjoyed long reigns and an unbroken succession passing smoothly from father to son. In 1793, the succession of this first dynasty of Babylon (also known simply as the Amorite Dynasty) passed to Hammurabi (1792–1750). Hammurabi was one of the great rulers of history, a man of personal genius and vision who left an indelible impress on all his heirs. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

At first Hammurabi's prospects seemed anything but favorable. A celebrated Mari letter phrased his situation in classic terms: "There is no king who is all-powerful by himself: ten or 15 kings follow in the train of Hammurabi of Babylon, as many follow Rîm-Sin of Larsa, as many follow Ibal-pî-El of Eshnunna, as many follow Amut-pî-El of Qatna, and 20 kings follow in the train of Yarim-lim of Yam ad" (G. Dossin, Syria 19 [1938], 105–26). A lesser personality would have fallen victim to the struggles between these and other major powers of the time, but by an adroit alternation of warfare and diplomacy, Hammurabi succeeded where others had failed. He maintained the friendship of Rîm-Sin until his 30th year, when, in defeating him, he fell heir as well to all that Larsa had conquered. He avoided challenging Shamshi-Adad, another older contemporary, but defeated his successor two years after disposing of Rîm-Sin. Three years later, he conquered Mari, where Zimri-Lim had reestablished a native dynasty after the Assyrian defeat. Eshnunna and the lesser states across the Tigris fell to Hammurabi's armies before the end of his reign, and only the powerful kingdoms beyond the Euphrates-notably Yam ad and Qatna — escaped his clutches.

Hammurabi was a zealous administrator, and his concern for every detail of domestic policy is well documented in his surviving correspondence. He is most famous for his collection of laws which, in the manner initiated by Ur-Namma of Ur, and elaborated in the interval at Isin ("Code of Lipit-Ishtar") and Eshnunna, collected instructive legal precedents as a monument to "The King of Justice." That was the name he gave to the stelae inscribed with the laws which were erected in Babylon and, no doubt, in other cities of his kingdom. Fragments of several, including a well-pre-served one, were carried off centuries later as booty to Susa, where they were rediscovered in modern times; some of the missing portions can be restored from later copies prepared in the scribal schools, where the laws of Hammurabi, recognized as classic, were copied and studied for over a thousand years more. Framed in a hymnic prologue that catalogued his conquests, and an epilogue that stressed his concern for justice, the laws do not constitute a real code. They are not noticeably adhered to in the innumerable contracts and records of litigation from this and subsequent reigns. However, they remain the starting point for the understanding of Babylonian and all Near Eastern legal ideals. Many of their individual formulations, as well as their overall arrangement, are paralleled by the casuistic legislation of Exodus and Deuteronomy.

It is important, in spite of all this, to see Hammurabi's achievement in its proper perspective. His reunification of Mesopotamia, consummated at the end of his reign, survived him by only a few years. His son and successor had to surrender much of the new empire before he had ruled more than a decade. The extreme south was lost to a new dynasty, sometimes called the First Sealand Dynasty; across the Tigris, Emutbal and Elam regained their independence; and the Middle Euphrates was soon occupied by Hanean nomads from the desert and by Kassites (see below). The enduring legacy of Hammurabi lies rather in the legal, literary, and artistic realms, where his reign marked both the preservation and canonization of what was best in the received traditions and a flowering of creative innovations.

Unknown Dynasty of the First Babylonian Empire

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia: “ “The Amorite dynasty was succeeded by a series of eleven kings which may well be designated as the Unknown Dynasty, which has received a number of names: Ura-Azag, Uru-ku, Shish-ku. Whether it was Semite or not is not certain; the years of reign are given in the "King-List", but they are surprisingly long (60,-50-55-50-28, etc), so that not only great doubt is cast on the correctness of these dates, but the very existence of this dynasty is doubted or rejected by some scholars (as Hommel). [Source: J.P. Arendzen, transcribed by Rev. Richard Giroux, Catholic Encyclopedia |=|]

It is indeed remarkable that the kings should be eleven in number, like those of the Amorite dynasty, and that we should nowhere find a distinct evidence of their existence; yet these premises hardly suffice to prove that so early a document as the "King-List" made the unpardonable mistake of ascribing nearly four centuries of rule to a dynasty which in reality was contemporaneous, nay identical, with the Amorite monarchs. Their names are certainly very puzzling, but it has been suggested that these were not personal names, but names of the city-quarters from which they originated. Should this dynasty have a separate existence, it is safe to say that they were native rulers, and succeeded the Amorites without any break of national and political life.

Owing to the questionable reality of this dynasty, the chronology of the previous one varies greatly; hence it arises, for instance, that Hammurabi's date is given as 1772-17 in Hasting's "Dictionary of the Bible", while the majority of scholars would place him about 2100 B.C., or a little earlier; nor are indications wanting to show that, whether the "Unknown Dynasty" be fictitious or not, the latter date is approximately right. |=|

Saddam-era reconstruction of Babylon

Fall of the First Babylonian Empire to the Hittites and Kassarites

After Hammurabi’s death, the Babylonians were harassed by Indo-European tribes in the northern mountains. The Babylon empire came to an end when the Indo-European Hittites sacked Babylon in 1595 B.C. Around the same time the Hykos invaded Egypt and the Hurrians occupied Syria. The late second millennium B.C. has been called “the first international age.” It was a time when there was more interaction between kingdoms.

Around the second millennia B.C. the Indo Europeans tribes from north of India similar to the Aryans invaded Asia Minor. The Hittites, and later the Greeks, Romans, Celts and nearly all Europeans and North Americans descended from these tribes. They carried bronze daggers. The Hittite Empire dominated Asia Minor and parts of the Middle East from 1750 B.C. to 1200 B.C. Once regarded as a magical people, the Hittites were known for their military skill, the of development of an advanced chariot, and as one of the first cultures to smelt iron and forge it weapons and tools. They fought with spears from chariots and did not possess more advanced composite bow.

After a period of increasing turmoil and internal weakness, Babylon was taken over by Kassites, an Iranian people, in about 1575 B.C. Their rule seems to have had little discernable effect on Babylon’s political structure, but the lack of written records from this period makes certainty impossible. [Source: Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments, Encyclopedia.com]

The Kassites, a tribe from the Zagros mountains in present-day Iran, arrived in Babylonia and filled a vacuum left by the Hittite invasion. The Kassites, controlled Mesopotamia from 1595 to 1157 B.C. They introduced war chariots, The Kassites were defeated by the Elamites in 1157 B.C. A 300-year Middle Eastern Dark lasted from 1157 to 883 B.C. During this period the Assyrians in what is now northern Syria gained strength.

See Separate Article: BABYLON AND BABYLONIA: GEOGRAPHY AND OCCUPIERS africame.factsanddetails.com

Babylon’s Rebirth Under the Neo-Babylonians

By the middle of the twelfth century, power had passed to another Iranian people, the Elamites, though the powerful Assyrians were soon threatening from the north. They would dominate Babylon for the next five hundred years, until their downfall in about 625 B.C. at the hands of Nabopolassar (d. 605B.C.), the leader of the Chaldean people, who came from what is now Kuwait. During their rule some of the most familiar events of Babylonian history occurred, including the construction of the Hanging Gardens and the conquest of Jerusalem, both of which were the work of Nabopolassar’s son, Nebuchadrezzar II (c. 630–562B.C.). [Source: Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments, Encyclopedia.com]

In 539 B.C. the Persians, in concert with the priests of Marduk, seized Babylon without a fight. The city’s economic and cultural prominence continued until the Persian king Xerxes I (c. 519–465B.C.) plundered it and destroyed its walls after a failed rebellion in 482 B.C. The effects of Xerxes’ revenge were permanent.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024