Home | Category: Babylonians and Their Contemporaries

EBLA

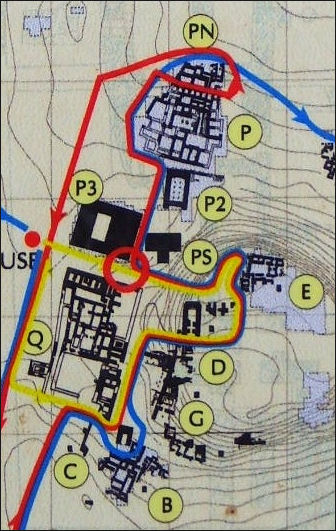

Ebla main buildings Ebla was ancient city-state in present-day northwestern Syria at Tell Mardikh. that rivaled Egypt and Mesopotamia and flourished from around 2,600 to 2000 B.C. Once thought to be a small insignificant ancient Middle East city, it is now regarded as having been a major economic center that traded with ancient cities such as Byblos, Damascus and Ur. The fact they were named on Eblaite tablets provides evidence that many of these cities are older than they were thought to be. [Source: Howard La Fay, National Geographic, December 1978]

Ebla prospered under the reign of five influential kings and competed with Saragon of Akkad, the founder of the first Mesopotamian empire, for control of the Fertile Crescent and the Euphrates River. Ebla is believed to be an important precursor to powerful Syrian states such as Assyria and helped spread Semitic culture that later produced the Hebrews and Arabs.

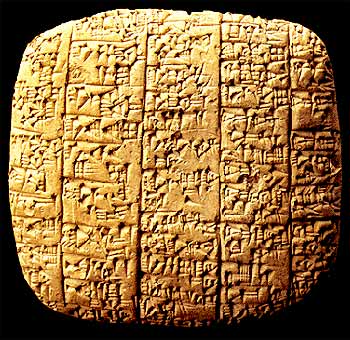

The Ebla civilization was a collection of city states under the control of Ebla. Among the important artifacts unearthed in Ebla when the site was discovered in 1964 by Italian archeologists were 17,000 clay tablets written in an early cuneiform Semitic language, now referred to as Eblaite. The world's earliest known bilingual dictionary, recording the Eblaite and Sumerian languages, was among these tablets.

Ebla was discovered in 1964 by Paulo Matthiae, an archaeologist from the University of Rome, who also did excavations at a site called Tell Mardikh in Syria. When news of Ebla was revealed, University of Chicago archaeologist Dr. Ignace J. Gelb told National Geographic, "These discoveries reveal a new culture, a new language, a new history. Ebla was a might kingdom, treated on a an equal footing with he most powerful states of the time."

Books: Matthiae, Paolo "Ebla and the Early Urbanization of Syria." In Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, edited by Joan Aruz with Ronald Wallenfels, pp. 165–68.. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003. Weiss, Harvey, ed. Ebla to Damascus: Art and Archaeology of Ancient Syria. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, 1985.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BABYLON AND BABYLONIA: GEOGRAPHY AND OCCUPIERS africame.factsanddetails.com

OLD BABYLONIANS: THEIR HISTORY, ACHIEVEMENTS, RISE AND FALL africame.factsanddetails.com ;

BABYLON GOVERNMENT: RULERS, LAWS, HAMMURABI africame.factsanddetails.com ;

OLD BABYLON AND THE BIBLE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

BABYLONIAN LIFE, RELIGION AND CULTURE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

RIVALS AND CONTEMPORARIES OF THE BABYLONIANS: ELAM, EMAR, MASHKAN africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUCCESSORS OF THE BABYLONIANS: MITANNI, HURRIANS, QATNA AND KASSITES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ebla: A New Look at History” by Professor Giovanni C. Pettinato (1991) Amazon.com;

“Ebla and its Landscape: Early State Formation in the Ancient Near East” by Paolo Matthiae and Nicoló Marchetti (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Archives of Ebla: An Empire Inscribed in Clay”by Giovanni Pettinato (1981) Amazon.com;

“Ebla to Damascus: Art and Archaeology of Ancient Syria” by M.D. Walters Art Gallery Baltimore, Harvey Weiss, et al. (1985) Amazon.com;

“Ebla and Its Archives: Texts, History, and Society”| by Alfonso Archi (2015) Amazon.com;

“Ebla and Beyond: Ancient Near Eastern Studies After Fifty Years of Discoveries at Tell Mardikh: Proceedings of the International Congress Held in Rome, 15th-17th December 2014

by Paolo Matthiae, Frances Pinnock, et al. (2018) Amazon.com;

“Ebla: An Archaeological Enigma” by Michael Bermant, Chaim; [and] Weitzman (1979) Amazon.com;

“A History of Babylon (2200 BC - AD 75" by Paul-Alain Beaulieu (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian Empire” by Enthralling History (2022) Amazon.com;

“The City of Babylon: A History, C. 2000 BC - AD 116" by Stephanie Dalley (2021) Amazon.com;

“The First Great Powers: Babylon and Assyria” by Arthur Cotterell (2019) Amazon.com;

“Civilizations of Ancient Iraq” by Benjamin R. Foster and Karen Polinger Foster ((2009) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Ancient Near East” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2003) Amazon.com;

Ebla City

Ebla may have been home to as many as 250,000 people. About 30,000 people lived inside the 50-foot-high walls of Ebla, and the remainder of the population lived in suburbs and satellite towns outside the walls and paid taxes in grain and livestock.

The king's palace was located on a hill (an acropolis). Around it were the quarters for 11,700 functionaries that served the palace. In the remains of the old palace, plastered wall and sockets that held the wooden shelves that houses the cuneiform tablets can still be seen. The monumental stairway was once inlayed with shells. The dais where the king spoke before crowds in the spacious audience court still stands.

The ruins of Ebla consists of a monumental gate, a massive wall, cisterns, temples and a great palace (destroyed in the 23rd century B.C. ), where archaeologists found a library with 15,000 cuneiform tablets. The tablets endured because the palace was burnt down and the inferno turned the palace library into an oven that baked the tablets into a hard ceramic that have held up against time.

Ebla Government and Trade

The Eblaite kings did not inherit the throne they were elected. Ebrrium, the most powerful Ebla kinf, was elected to four seven years terms and ruled for 28 years. Anointed before they took the throne like their Old Testament counterparts, the Eblaite kings were responsible for looking after widows, orphans and the poor as well as hold together a strong and united kingdom. If they failed to look after the disadvantaged they were ousted by a group of elders. Citizens aired their grievances before the king in the audience court of the king's palace.

Ebla produced the oldest surviving peace treaty, an agreement between Ebla and the neighboring kingdom of Abarsal. Even so the Eblaites could fight when they needed to. Describing the conquest of a village on the way to Mari, one general wrote his king, "The town of Aburu and the town of Ilgi...I besieged and conquered...piles of corpses I gathered in the land."

Ebla traded with ancient cities such as Byblos, Damascus, Gaza Mari, Assur, Kish, Khamazi and Ur. Mari, another great Mesopotamian city, was about 160 miles from Ebla. The royal palace in Mari had 300 rooms and courts. Ebla conquered Mari.

Ebla Tablets

The palace library at Ebla contained thousands of tablets that were excavated by an Italian expedition in1975. These showed that Ebla had been a major commercial center. The tablets, written in a Canaanite language (Eblaite), date from c.2500 B.C. Ebla had recently adopted Sumerian writing and wrote in Sumerian more often than in its own language [a Semitic language related to modern Hebrew and Arabic]. Archaeologists found some 16,000 clay tablets; 80 percent were written in Sumerian. The remainder, written in a previously unknown language, contain the oldest reference to Jerusalem and several other Hebrew proper names. [Source: Internet Archive, from UNT]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In 1964, Italian archaeologists began to excavate a mound in northwestern Syria known as Tell Mardikh. From 1975, work concentrated on an area they called "G." Here was discovered a palace dating to the second half of the third millennium B.C. Thousands of well-preserved cuneiform tablets were found in palace G demonstrating Ebla's close links to southern Mesopotamia, where the script had developed. In one of the palace rooms, over 14,000 tablets were excavated. The larger tablets had originally been stored on shelves but had fallen onto the floor when the palace was destroyed. The find spots of the tablets allowed the excavators to reconstruct their original position: they were stored by subject. The Ebla tablets record the cultural, economic, and political life of northern Syria. The majority of the tablets are inscribed in the local Semitic language, known today as Eblaite. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "Ebla in the Third Millennium B.C.", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002, metmuseum.org \^/]

The royal archive of Ebla was preserved by chance when Ebla was attacked and the palace contents were buried under the building's rubble. Sargon and Naram-Sin of Akkad, the conquerors of much of Mesopotamia, each claim to have destroyed Ebla, but the exact date of destruction is the subject of continuing debate.

Ebla Writing and Contents of the Tablets

Ebla clay tablet Most of tablets in the library were inscribed with commercial records and chronicles like those found in Mesopotamia. Describing the importance of the tablets, Italian archaeologist Giovanni Pettinato told National Geographic, "Remember this: All the other texts of this period recovered to date are not total a forth of those from Ebla."

The tablets are mostly around 4,500 years old. They were written in the oldest Semitic language yet identified and deciphered with oldest know bilingual dictionary, written in Sumerian (a language already deciphered) and Elbaite. The Elbaites wrote in columns and used both sides of the tablets. Lists of figures were separated from the totals by a blank column. Treaties, description of wars and anthems to the gods were also recorded on tablets.

Ebla's writing is similar to that of the Sumerians, but Sumerian words are used to represent syllables in the Eblaite Semitic language. The tablets were difficult to translate because the scribes were bilingual and switched back and forth between Sumerian and the Elbaite language making it difficult for historians to figure which was which.

The oldest scribe academies outside of Sumer have been found in Ebla. Because the cuneiform script found on the Ebla tablets was so sophisticated, Pettinato said "one can only conclude that writing had been in use at Ebla for a long time before 2500 B.C."

Ebla Culture and Art

The craftsmen at Ebla were skilled in metallurgy, textiles, ceramics and woodworking. They produced fine sell-inlaid tables and stunning red cloth interwoven with gold that resembles brocades still found in Syria today. Ebla is also know for its "highly original statuary" and fine gold ornaments unearthed from royal tombs.

Important deities and heroic images found on their art and functional objects included a figure with an ax that symbolized authority. The four main gates into the city were dedicated to different gods. Each city quadrant was overseen by a “ lugal” , a kind of ward boss.

Artifacts from Ebla provide evidence of Ebla's close relationship with the Mediterranean world and Egypt. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Exquisite sculpture in the round was recovered. Composite statues had been created from different colored stones. Much of the artistic style preempts, and possibly influences, the quality work of the Akkadian empire (ca. 2350–2150 B.C.).” [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "Ebla in the Third Millennium B.C.", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York:The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002, metmuseum.org ]

Decline of Ebla

Ebla Ebla declined after the city was sacked by the Akkadians about 2250 B.C. It was rebuilt and the sacked again in 2000 B.C. by the Elamites and Amroites; then rebuilt again and began to decline again around 1800 B.C. By 1600 B.C. it had disappeared from history.

The Eblaite language is believed to have survived in Canaanite cities such as Ugarit, an important 14th century B.C. Mediterranean port, and then was passed on to the Semitic tribes of the Middle East, which included the people of Ugarit, Phoenicians, Hebrews and later the Arabs.

Around 2000 B.C. a number of Syrian cities were abandoned or shrunk in size. Some have suggested this occurred because of climate change. Other say it happened because of environmental degradation. Archaeologists have checked botanical and faunal remains for clues but this haven’t come up with anything firm.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Mashkan, Minnesota State University

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024