Home | Category: Babylonians and Their Contemporaries

MESOPOTAMIAN CITY STATES

Elamite Gopat

From about 2350 B.C. to the Persians took over in 450 B.C., Mesopotamia was largely ruled by Semitic-speaking dynasties with cultures derived from Sumer. They include the Akkadians, Eblaites and Assyrians. They fought and traded with the Hittites, Kassites and Mitanni, all possibly of Indo-European descent. [Source: World Almanac]

All of these cultures incorporated many elements of Sumerian culture, including concepts of city life,, civic organization, law and monumental architecture.

Many ancient sites from this period and region have “Tel” in the name. “Tel” is an Arabic word meaning “mound.” Describing on such site archaeologist Glenn Schwartz wrote in Natural History magazine, “It is an archaeological time capsule, with layers of mud bricks, stones, artifacts and other materials that have accumulated for thousands of years as buildings were lived in, abandoned, fell into ruin, and finally served as foundations for a new generation of buildings.”

Tell Hamoukar and other sites in northern Syria and southwestern Turkey — including Tell Barak in northeast Syria and Hacinebi and Arslamtepe in southeast Turkey, which date to 4000 B.C. to 3000 B.C. — seem to have some of the attributes of the famous Mesopotamia sites in southern Iraq — monumental architecture, division of labor and stratification of society — 500 years before there was any contact with between the regions.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BABYLON AND BABYLONIA: GEOGRAPHY AND OCCUPIERS africame.factsanddetails.com

OLD BABYLONIANS: THEIR HISTORY, ACHIEVEMENTS, RISE AND FALL africame.factsanddetails.com ;

BABYLON GOVERNMENT: RULERS, LAWS, HAMMURABI africame.factsanddetails.com ;

OLD BABYLON AND THE BIBLE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

BABYLONIAN LIFE, RELIGION AND CULTURE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

EBLA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUCCESSORS OF THE BABYLONIANS: MITANNI, HURRIANS, QATNA AND KASSITES africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Civilizations of Ancient Iraq” by Benjamin R. Foster and Karen Polinger Foster ((2009) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Ancient Near East” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2003) Amazon.com;

“Time at Emar: The Cultic Calendar and the Rituals from the Diviner's Archive”

by Daniel E. Fleming (2000) Amazon.com;

The Anatomy of a Mesopotamian City: Survey and Soundings at Mashkan-shapir”

by Elizabeth C. Stone, Paul Zimansky (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Elamite World” by Javier Álvarez-Mon , Gian Pietro Basello, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Proto-Elamite Settlement and Its Neighbors: Tepe Yaya Period IVC” by Benjamin Mutin and C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky (2014) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Iran: Rise and Fall of the Elamite and Iranian Civilization”

by Amir Reza (2021) Amazon.com;

“Lesser Known People of The Bible: Elam and The Elamites” by Dante Fortson (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Elam CA. 4200–525 BC” by Javier Álvarez-Mon (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State” (Cambridge World Archaeology) by D. T. Potts (2016) Amazon.com;

“A Handbook of Gods and Goddesses of the Ancient Near East: Three Thousand Deities of Anatolia, Syria, Israel, Sumer, Babylonia, Assyria, and Elam” by Douglas R. Frayne , Johanna H. Stuckey, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“A History of Babylon (2200 BC - AD 75" by Paul-Alain Beaulieu (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian Empire” by Enthralling History (2022) Amazon.com;

“The City of Babylon: A History, C. 2000 BC - AD 116" by Stephanie Dalley (2021) Amazon.com;

“The First Great Powers: Babylon and Assyria” by Arthur Cotterell (2019) Amazon.com;

Elamites

The Elamites (2400 B.C. - 539 B.C.) were one of the great destroyers of Mesopotamian culture but also creators of their own culture. They emerged in what is now southwestern Iran and established a capital named Susa. They periodically battled with the Sumerians and destroyed Ur in 2000 B.C. They remained on the scene long enough to sack Babylon in the 12th century B.C. and carry the slab with Hammurabi’s legal code (See Babylonians) back to Susa.

At the high point of their power in the 13th century B.C. , the mighty Elamite ziggurat in the city of Dur Untash towered over the realm. Partly restored and found at a site called Choga Zanbil in Iran, it was one of the largest ziggurats in the world. The Elamites cultural influence continued after they were absorbed by Persia.

The Elamites were believed have grown rich from trade. Their kingdom were located between Mesopotamia and the eastern highlands that provided it with the minerals they craved: lapis lazuli, carnelian and soapstone.

The Elamites as a Middle East power lasted until 646 B.C. when the Assyrians stormed Elam and sacked Susa. They joined the Persian Empire in 539 B.C. when Cyrus the Great captured Susa.

See Separate Article: BRONZE AGE, PRE-PERSIAN AND MESOPOTAMIA-ERA IRAN factsanddetails.com

Ebla

Elamite worshipper

Ebla was ancient city-state in present-day northwestern Syria at Tell Mardikh. that rivaled Egypt and Mesopotamia and flourished from around 2,600 to 2000 B.C. Once thought to be a small insignificant ancient Middle East city, it is now regarded as having been a major economic center that traded with ancient cities such as Byblos, Damascus and Ur. The fact they were named on Eblaite tablets provides evidence that many of these cities are older than they were thought to be. [Source: Howard La Fay, National Geographic, December 1978]

Ebla prospered under the reign of five influential kings and competed with Saragon of Akkad, the founder of the first Mesopotamian empire, for control of the Fertile Crescent and the Euphrates River. Ebla is believed to be an important precursor to powerful Syrian states such as Assyria and helped spread Semitic culture that later produced the Hebrews and Arabs.

The Ebla civilization was a collection of city states under the control of Ebla. Among the important artifacts unearthed in Ebla when the site was discovered in 1964 by Italian archeologists were 17,000 clay tablets written in an early cuneiform Semitic language, now referred to as Eblaite. The world's earliest known bilingual dictionary, recording the Eblaite and Sumerian languages, was among these tablets.

Ebla was discovered in 1964 by Paulo Matthiae, an archaeologist from the University of Rome, who also did excavations at a site called Tell Mardikh in Syria. When news of Ebla was revealed, University of Chicago archaeologist Dr. Ignace J. Gelb told National Geographic, "These discoveries reveal a new culture, a new language, a new history. Ebla was a might kingdom, treated on a an equal footing with he most powerful states of the time."

Books: Matthiae, Paolo "Ebla and the Early Urbanization of Syria." In Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, edited by Joan Aruz with Ronald Wallenfels, pp. 165–68.. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003. Weiss, Harvey, ed. Ebla to Damascus: Art and Archaeology of Ancient Syria. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, 1985.

Amorites

The Amorites were an ancient Semitic-speaking people that dominated the history of Mesopotamia, Syria, and Palestine from about 2000 to about 1600 B.C. In the oldest cuneiform sources (c. 2400–c. 2000 B.C.), the Amorites were equated with the West, though their true place of origin was most likely Arabia, not Syria. They were troublesome nomads and were believed to be one of the causes of the downfall of the 3rd dynasty of Ur (c. 2112–c. 2004 bc). [Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica]

According to Encyclopaedia Britannica: “During the 2nd millennium B.C., the Akkadian term Amurru referred not only to an ethnic group but also to a language and to a geographic and political unit in Syria and Palestine. At the beginning of the millennium, a large-scale migration of great tribal federations from Arabia resulted in the occupation of Babylonia proper, the mid-Euphrates region, and Syria-Palestine. They set up a mosaic of small kingdoms and rapidly assimilated the Sumero-Akkadian culture. It is possible that this group was connected with the Amorites mentioned in earlier sources; some scholars, however, prefer to call this second group Eastern Canaanites, or Canaanites.

“Almost all of the local kings in Babylonia (such as Hammurabi of Babylon) belonged to this stock. One capital was at Mari (modern Tall al- arīrī, Syria). Farther west, the political centre was alab (Aleppo); in that area, as well as in Palestine, the newcomers were thoroughly mixed with the Hurrians. The region then called Amurru was northern Palestine, with its centre at Hazor, and the neighbouring Syrian desert. In the dark age between about 1600 and about 1100 bc, the language of the Amorites disappeared from Babylonia and the mid-Euphrates; in Syria and Palestine, however, it became dominant. In Assyrian inscriptions from about 1100 bc, the term Amurru designated part of Syria and all of Phoenicia and Palestine but no longer referred to any specific kingdom, language, or population.”

See Separate Article: AMORITES: MARI. HISTORY, UNUSUAL LANGUAGE africame.factsanddetails.com ; BIBLICAL AMORITES africame.factsanddetails.com

Emar

Emar (modern Tell Meskene) is an archaeological site near Aleppo in northern Syria. Situated on a bend of the mid-Euphrates, now on the shoreline of the man-made Lake Assad near the town of Maskanah, it has been the source of many cuneiform tablets, making it rank with Ugarit, Mari and Ebla among the most important archeological sites of Syria. In these texts, dating from the 14th century BC to the fall of Emar in 1187 BC, and from excavations begun the 1970s, Emar emerges as an important Bronze Age trade center and link between of Upper Mesopotamia and Anatolia-Syria. Unlike those found in other cities, the tablets found at Emar, mostly in the Akkadian language, are not royal or official documents, but rather records of private transactions, judicial records, dealings in real estate, marriages, last wills, formal adoptions and the like. In the house of a priest, a library contained literary and lexical texts in the Mesopotamian tradition, and ritual texts for local cults. [Source: Wikipedia]

Jean-Claude Margueron wrote: “The origin of Emar is yet unknown. It owes its appearance in history to the archives at Ebla, a kingdom which had evidently become prosperous by the beginning of the second half of the third millennium....Although it was an economic metropolis of Northern Syria during one and a half millennia and surely constantly tugged between politically prominent cities like Ebla or Aleppo, Emar never seems to have played a major political role. The results of its excavation show us only one and a half century of its existence at a time when it was in complete submission to Hittite power. On the other hand, ever since the third millennium, Emar had been, as point of transfer in trade between Syria and Mesopotamia, one of the crucial components of the system which governed, to varying degrees, the economy of the Near East during the Bronze Age. From the fourteenth to the beginning of the twelfth century, under Hittite dominion, Emar's population seems to have been very active, at times even insubordinate. [Source: Jean-Claude Margueron, Translated by Veronica Boutte, Internet Archive, from Emory University /+/]

“The exploration of Emar has provided a detailed view of the life of a Hittite province during the largest expansion of the empire, of its territorial organization, and of the value this crossroads represented for international relations. Its discovery has illuminated political, cultural, and economical relations between the central power and a border town in the thirteenth century. Moreover, its excavation has raised questions of cultural influence, of assimilation, and redistribution of the features of civilization; displayed the economical role of a town as a point of transfer during fifteen centuries; and finally, made prominent the technical skills of Late Bronze Age populations to carry out urban construction as well as large-scale regional settlement.” /+/

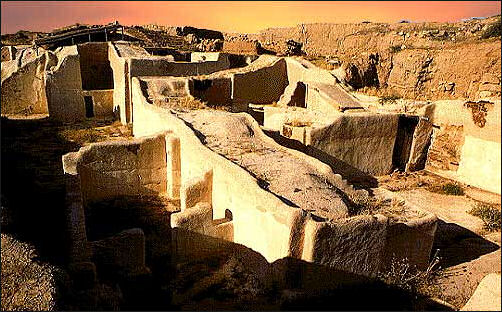

Ebla royal palace

History of Emar

Jean-Claude Margueron wrote: “Four royal names are known to us from the Ebla archives: EN-zi-Da-mu, Ib-Da-mu, Is-gi-Da-mu, and Na-an-Da-mu. An alliance of dynasties probably existed between Ebla and Emar, since several texts from Emar mention Queen Tisa-Lim coming originally from Ebla. Reciprocal commercial activity certainly formed the basis of their relationship. We know that fairly significant quantities of clothing and precious metal objects were sent to Emar, though we have no idea what Emar shipped to Ebla in exchange. However, beyond the appearance of names of merchants in the texts, Emar's economic activity as a strategic point of transfer on the Syro-Mesopotamia axis is highly likely in this period. [Source: Jean-Claude Margueron, Translated by Veronica Boutte, Internet Archive, from Emory University /+/]

“The archives at Mari paint a picture of Emar at the beginning of the eighteenth century B.C.. This exceptionally rich documentation, which illuminates the Syrian world particularly, displays Emar as a city at the heart of the Syrian trade between Yamhad, Qatna, and Carchemish. Though the Mari documents do not emphasize intense waterway traffic with the Euphrates capital-as though the river no longer constituted such an important asset as in the past-Emar appears as the key factor in Syro-Mesopotamian relations. Politically, Emar belonged to a more restricted world composed by all the towns on the Euphrates. Did it play a major role? Nothing is known with certainty: Emar may have paid tribute to three different kings (most certainly to the King of Aleppo and probably to the Kings of Mari and Carchemish). This would show very limited autonomy, even if occasionally the city showed some signs of independence.

“The texts from Ugarit and Nuzi mention Emar. With the Late Bronze Age however, a more precise and less speculative history can be presented, thanks to the discovery of hundreds of documents in the various fields opened during excavations . The primary areas of excavation produced a hilani (palace of the local king), temples to Baal and Astart at the highest point of the site, private homes and personal archives, and, most of all, the library of the Diviner buried in the ruins of the Pantheon (temple M-1). /+/

“The city seems clearly to have been destroyed around 1187 B.C., during the great cataclysm that devastated Syria and the Hittite Empire. At least this seems reasonable to deduce from a tablet found on the floor of a private home in Field A. The tablet refers to the Kassite calculation: "Additional Ellul, second year of Melisihu," King of Babylonia. Even if not all houses bear traces of violent conflagration, it looks as though the city has been ravaged, fallen as a result of a siege. For now, our sources are silent about this event, and it would be risky to blame it on the Peoples of the Sea rather than any other people. /+/

rivals and contemporaries of the Babylonians

Emar Organization and Buildings

Jean-Claude Margueron wrote: ““The city was laid out following a design resembling a rectangle approximately seven hundred by one thousand meters. Excavations in Field Y, located on the side of the human-made valley, revealed the presence of a rampart. There were no traces of gates however, though they probably existed at the center of each side, based on the topography of the tell. The entire eastern half of the site was covered by the Byzantine town of Barbalissos and the Arab town of Balis and remains terra incognita. Perhaps this is where the main decision-making center of the Hittite power was located, since the lone probe made in the area gave us a Hittite tablet. Some of the major thoroughfares have been unearthed, while others can be deduced from the topography. However, none of the principal lines of the network can any longer be discerned. The major sanctuary of the city, dedicated to the pair Baal/Astart, was situated on the southwest at summit point of the site, so as to be visible everywhere. The local king's palace occupied another eminent position at the northwest corner. This location permitted a watchful view over the city and the port which no doubt bordered the northern side of the town. Other temples were integrated into the regular urban fabric. [Source: Jean-Claude Margueron, Translated by Veronica Boutte, Internet Archive, from Emory University /+/]

“The local king's palace, situated on the promontory in the northwest overlooking the valley, takes the form of a complex monumental building: it is in actuality one of the oldest palaces of the hilani type. It belongs to the Bronze Age, while most buildings of this type are generally considered characteristic of the Iron Age. The structure possesses all the characteristics which will later constitute this particular category of Syrian palaces. Its facade clearly boasted a second story. A colonnaded portico led to two oblong rooms, with the second doubtless playing the role of the throne room. Dependent structures were located to the south. This is the first time that such a good model of the hilani type has been found at such an early period. The discovery therefore challenges the breach often fixed between the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. A Hittite origin of the building form seems most probable. As the archives found in the building testify, this is where the local king used to live. But despite its very dominant location, and the interest it offers for architectural history, one should not assign too much importance to the royal authority who resided in this palace. /+/

“Emar's excavators found four temples. The first two took the form of a set of temples associated with a cultic terrace: the major official sanctuary of the city situated on the pinnacle of the tell overlooking, besides the western and southern valleys, the whole urban area and its immediate surroundings. Both of them were designed in the megaron style (one elongated room for the Holy Place with its offering table, special paraphernalia for rituals, and podium for the deity or the Most Holy Place), and they were aligned almost parallel, doors opening to the east, on each side of a street leading to a vast cultic esplanade at their rear. An altar was erected on the southern edge of the esplanade, and some cupholes (occasionally of a large diameter, but with no visible function) dotted the floor. Based on a few tablets collected in this temple constellation, it looks as though the temple in the south, located slightly above the rest, would have been dedicated to Baal, while inside the northern temple, Astart would have been worshipped. /+/

“The third sanctuary (M-2), sometimes identified as a Pantheon because it seems to have been dedicated to all the gods, was unearthed in Field M. It, too, was designed as a megaron, with the typical structures found in Field E, particularly a small cultic esplanade also located behind the temple. But this temple possessed the peculiarity of being equipped with an annex consisting of three rooms on its long eastern side. Here excavators unearthed the Diviner's archives, which might have fallen from an upper floor. The Diviner was an important figure whose reputation reached the court of the Great Hittite king. /+/

“The last temple, found slightly to the north and not too far from the previous one, was also fully integrated into the urban fabric. Of the same generic shape, but without a deep entry, it opened into a small room. Very rich artifacts came out of it (glazed ceramics; pearls; a carved caprine horn, one of the most impressive pieces at Emar, artistically), but it was impossible to find out which divinity was worshipped in the temple. It is remarkable to see that all the temples belong to the model commonly found in Syria since the third millennium and that no attempts by the Hittites were made to replace them with their own.

cities and sites in Syria at the time of the Assyrians

Emar Houses and Daily Life

Jean-Claude Margueron wrote: “Diggers excavated about thirty private homes in their entirety or partially. In two Fields (A and D), they even unearthed groups of houses, true clusters organized with the terraces. The design of the houses was strictly uniform: one could practically speak of a standard design consisting of a large downstairs room, generally rectangular and opening onto the street, and two small rooms of indistinguishable function, but separated from each other, located on the opposite side from the entrance. The structure of the houses, the frequent presence of interior stairways, and traces of fire in the debris show that this constellation of rooms was roofed. Often an upper floor was built above the smaller rooms. Everything else was surmounted by an open-air terrace. No courtyards were ever discovered associated with the houses examined. The bread oven was to be found inside the larger room, as well as familial or commercial storage. Therefore, it seems that daily living took place mostly on the upper floor, in the master room, and on the terrace. This house form was very widespread, not only in the bend of the Euphrates, but in North Syria generally, and sometimes in neighboring regions during the second millennium. However, it is not common to Hittite customs. Rather, it represents a regional style in use since the third millennium and systematically adopted as the main model for the new Emar. [Source: Jean-Claude Margueron, Translated by Veronica Boutte, Internet Archive, from Emory University /+/]

“All building types-temples, palaces, and houses-produced diverse material finds which display vividly the condition of daily life. The city definitely experienced great prosperity during its one and a half centuries of existence. The furnishings found inside temples and palaces make this obvious. One should particularly note: bronze figurines (divine and bovine); glass and faience containers and ornaments; glazed ceramics; a female ivory head (unfortunately severely charred); weaponry (a beautiful sword of a mixture of iron and bronze); a wooden box with ivory lids; remains of gold and silver leaf; and a silver crescent pendant (perhaps representing bovine horns). [Source: Jean-Claude Margueron, Translated by Veronica Boutte, Internet Archive, from Emory University /+/]

“Besides ceramics, occasionally collected in large quantities, the houses produced stone and metallic objects illustrating both day-to-day needs and the activities of city merchants: beer filters; containers; arrow and javelin heads; scales of armor; needles and scissors; long nails; bronze scrapers; millstones; mortars; many kinds of grindstones; pestles; various tools; and stone rings. /+/

Of particular interest are the terra cotta "architectural models." “With over thirty examples, this is the richest collection produced to date by a Near Eastern site...One type takes the form of a rectilinear tower topped with a corbeled crown whose sharply pointed angles suggest the shape of horns. The other type represents, so it seems, traditional homestyles close to the standard design found at Emar: elongated building space with an upstairs room opening over a terrace. Divided windows, triangular or circular openings, and a front door permit comparisons with real architecture, even if some of the aspects of the decoration (plated naked female figurines, lions, ropes, plant-life symbols) bear only a distant connection to housing. Therefore, one can recognize in certain characteristics, more of the potter's artistic expression than the architect's. The role of these objects, especially coveted in the bend of the Euphrates, is not very clear, but a religious significance should not be excluded. /+/

Emar Art

Jean-Claude Margueron wrote: “Art is not well represented, perhaps because of the final looting, perhaps because of the fundamentally commercial nature of residents' activities. Sculpture is especially scarce, except for the relief on a bowl fragment from the Temple of Astart and part of a small engraved stele. Other than that, one should note the many and extremely varied figurines, modeled and cast, as well as embossed reliefs. The double sanctuary of Baal and Astart offered some bronze, ivory, and parts of an ornament, probably architectural, made of glass pulp, all of it quite damaged by the fire which destroyed the city. Sanctuary M-2 produced a beautiful collection of fragmentary objects, usually cultic in nature: glazed ceramics, gypsum vases, pendants, and pearls. [Source: Jean-Claude Margueron, Translated by Veronica Boutte, Internet Archive, from Emory University /+/]

“Above all, the fascinating sculptured caprine horn found on the floor of the anonymous temple on Field M deserves emphasis. It is 24.2 cm long and divided into six tiered unequal registers: the primary motifs include scenes in which a man confronts a lion; profiles of hunters or warriors carrying bow, hatchet, spear, or lance; chariot ridden by an archer attacking a bovid; parade of lion with antelopes; sphinx; schematic plant life and fringes. All of these belong to the common repertoire for this period; one is struck by the rather clumsy look of the entire work, maybe because it was created in a local workshop. This underlines all the more the value of a few saving successes, such as the wounded bull. /+/

“In contrast, engraving preserved on eight hundred impressions on tablets is certainly one of the main treasures of the site. After elimination of duplicates, the collection of nearly four hundred different seals represents the most beautiful assemblage revealed so far in Northern Syria. Next to cylinder seals of the Mesopotamian kind which make up the largest series, one finds circular stamps (more rarely square) of the Anatolian type, and ring-stamps usually with hieroglyphic writing but used especially in North Syria. /+/

“In the seals one can observe the encounter of several artistic currents which exercised real influence on local traditions. Typical Syrian features intertwine with manifestly Babylonian sources, while the Mitannian imagery appears prominently as of the middle of the second millennium. Under Hittite domination, northern influences were very well received at Emar. This acceptance is indicated by the fact that the names of Semitic residents of Emar are rendered at the same time in Hittite hieroglyph and cuneiform characters, and that the use of the stamp is spreading without reducing use of the cylinder seal. /+/

“One of the main interests of this collection is in the diversity of styles offered: proof of an exceptional capacity to adapt to varied influences and of an eclecticism typical of a region at the crossroads of very diverse milieus. The two most richly represented collections undoubtedly express the contradictions of this land, both attached to its own traditions and under Hittite hegemony. The so-called "Syrian" collection, from local tradition, hides under some form of archaism, where the Mitannian, Babylonian, and even old Babylonian influences are very strong. The "Syro-Hittite" series reflects the nature of the political situation, since the engravers borrow extensively the themes and patterns of the occupying power.” /+/

Mashkan, a Rival of Babylon

Mashkan is is an archeological site in the desert about 90 miles southeast of Baghdad. The ancient city has not been occupied since it was sacked and burned around 1720 B.C. John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “Most ancient cities were inhabited for thousands of years, with the culture of one era building on top of another. This makes it difficult to separate layers of deposits to understand urban life of any given time. Mashkan-shapir, however, enjoyed one distinct 300-year period as a major trading and manufacturing center of 15,000 people, from about 2050 B.C. until it was sacked. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, April 11, 1989]

Scholars had known something of the city's existence from Babylonian documents. But most experts, if they thought much of it at all, had assumed that the site was farther south of ancient Babylon and thus closer to Larsa, Babylon's rival power. What followed in the inscriptions identified the king, Sin-iddinam of Larsa, who ordered the wall to be built and described how the army was mobilized for the task. The wall was erected about 1850 B.C., a time when the city was growing in stature.

Although nominally ruled by the city-state of Larsa in the south, Mashkan-shapir was becoming a strategic military and economic center on the trade routes between southern Mesopotamia and Assyria in the north and Iran in the east. In the early 18th century B.C., ambassadors from Hammurabi regularly called on Mashkan-shapir and the Babylonians gained control over the southern territory only after defeating that city's forces.

Moreover, when Hammurabi's empire began to collapse after his death in 1750 B.C., rebellions in Mashkan-shapir contributed to the decline of Babylon that would last until it regained eminence in the 7th and 6th centuries B.C.

Mashkan

Discovery of Mashkan

John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “Flakes of crumbling brick drew the archeologist step by step along the line where the wall of an ancient city of lower Mesopotamia once stood. The trail led to remnants of the south gate, and there on the ground lay a clay fragment bearing cuneiform inscriptions.” [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, April 11, 1989]

One name leaped out from the inscribed symbols: Mashkan. In that moment of discovery this January, Elizabeth C. Stone, the archeologist, knew she had found and identified one of the oldest lost cities in the cradle of civilization between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers of southern Iraq. It was without doubt the site of Mashkan-shapir, which flourished 4,000 years ago, becoming a capital of the rival power to rising Babylon. But the city had left little trace in history, except for references in the letters and law code of the great Babylonian ruler, Hammurabi.

Dr. Stone, associate professor of archeology at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, and her co-investigator and husband, Paul Zimansky, assistant professor of archeology at Boston University, announced the discovery in March 1988. They said that finding the remains of Mashkan-shapir could be one of the major developments in Mesopotamian archeology in more than 40 years. Other scholars cheered the news. William Hallow, professor of Assyriology at Yale University, said, ''It's always a happy day in archeology when someone nails down the identification of an ancient city.''

But archeologists doubted that Mashkan-shapir would prove to be as rich a lode as Ebla, an ancient city in Syria whose voluminous archives were uncovered in the 1970's to reveal a previously unknown language. They said that, depending on later findings, the site could rank in importance with Tell Leilan, the second major Mesopotamian find since World War II. In 1985, archeologists discovered that Tell Leilan in northern Mesopotamia had been the seat of a powerful kingdom in the 18th century B.C. and contained a major archive of royal correspondence. It afforded rare glimpses into life beyond the more celebrated cities of southern Mesopotamia, notably Bablyon.

The Mashkan-shapir discovery became the talk of archeology because it is the rare instance of a site of an ancient city being found and then being identified in one swift stroke. Archeologists must often dig for years before uncovering archives and monuments establishing the city's name and place in history. The identity of the new discovery was determined in the first six weeks of preliminary surveys. A Promising Site

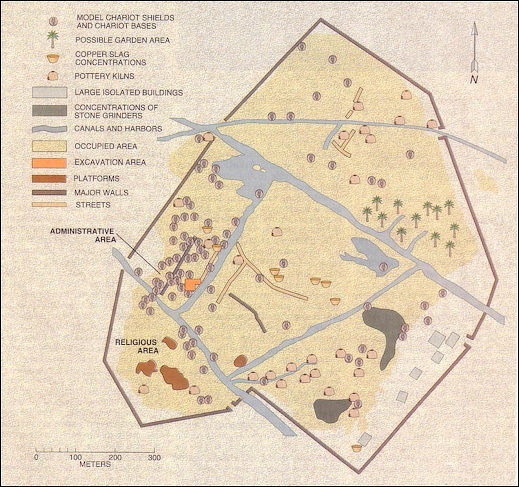

Mashkan map

Archeological Work at Mashkan

After aerial photographic surveys and some exploratory digging, Dr. Stone said: ''We have a whole city plan laid out there for us. We know where the canals were, the cemetery, the palace and religious quarters, the manufacturing area and the city wall. A complete, undisturbed city - that's what's really exciting about it as an archeological site.'' [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, April 11, 1989]

Because the city was suddenly abandoned, rather than falling into slow decline, Dr. Stone said, the ruins should include many domestic possessions the fleeing people left behind. The result could be an illuminating picture of daily life among all classes.

The uncovering of Mashkan began in 1975, when Robert McC. Adams, a University of Chicago archeologist who is now secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, noted a scattering of potsherds and other artifacts at the site and so included it in his comprehensive survey of promising places for future exploration. But Dr. Stone and Dr. Zimansky were the first to begin systematic exploration. In 1987, they collected fragments of clay figurines and metal objects on the surface there and traced faint discolorations in the sunbaked soil, which betrayed the outlines of buried or eroded brick building foundations.

The archeologists then examined satellite images of geological patterns revealing the course of the Tigris in earlier times and the routes of ancient canals and a branch of the river that had served the city. Closer aerial examination was hampered by Iraqi military restrictions against using aircraft for photography. But Dr. Zimansky was not deterred. He lofted a kite carrying an automatic camera and soon had pictures revealing all the important building sites, outlines of the city wall and other features that were not immediately apparent from the ground.

Returning to work at the in late 1988 Dr. Stone and Dr. Zimansky dug test trenches with the aerial photographs from the balloons as their guide. Their work was supported by the American Schools of Oriental Research and the National Geographic Society. Close to a dry riverbed the archeologists uncovered the religious quarter, consisting of mudbrick and baked brick platforms that must have supported temples dedicated to Nergal, the ancient Babylonian god of death, pestilence and other disasters. Elsewhere, model chariots in clay bear emblems portraying Nergal or the scythes with which he performed his work as the original grim reaper. This, then, was clearly a city built in honor of Nergal, as neighboring Ur was the city of Nanna, the moon god.

Other spot excavations located the cemetery, where the dead were buried in huge jars, accompanied by beads, copper amulets, weapons and other personal effects. Pottery and copper-bronze workshops were uncovered. The preliminary survey produced more than 600 artifacts, though there were no indications of valuable metals or jewels. The most prized finds so far are the many fragments of clay cylinders bearing inscriptions in the wedge-shaped Sumerian symbols known as cuneiform. The cylinders were about 12 inches long and 6 inches wide. Most of these, like the one Dr. Stone picked up at the south gate, were apparently commemorative objects placed in the foundation of the city wall.

Indeed, as translated by Piotr Steinkeller, professor of Assyriology at Harvard University, the inscription on each piece began with the same phrase: ''When the great lord, the hero, Nergal, in his overflowing heart verily caused his city Mashkan-shapir to rise and determined to build its wall in a pure place and to expand its dwellings . . . .'' ''There's no doubt,'' Dr. Steinkeller said, after examining the inscriptions and confirming Dr. Stone's initial conclusion. ''One couldn't hope for better evidence of the city's identity.''

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Mashkan, Minnesota State University

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024