Home | Category: Late Stone Age and Copper and Bronze Age / First Cities, Archaeology and Early Signs of Civilization

LIFE IN DURING THE NEOLITHIC AND BRONZE AGE PERIODS

Çatalhöyük (668 kilometers 415 miles southeast of Istanbul) is widely accepted as being the world's oldest village or town. Established around 7500 B.C. , it covered 32 acres and was home to between 3000 to 8000 people. Because of the way of the houses are packed so closely together it is hard to dispute it as being anything other than a village or town. [Sources: Ian Hodder, Natural History magazine, June 2006; Michael Batler, Smithsonian magazine, May 2005; Orrin Shane and Mine Kucuk, Archaeology magazine, March/April 1998]

Archaeological work at Çatalhöyük has revealed a large community of Stone Age people beginning to reject nomadic life. Artifacts and structures uncovered at Çatalhöyük over the years suggest the people living at the site were pioneers of early farming and animal domestication. They cultivated wheat and barley and tended sheep and goats. Çatalhöyük has been a pioneer in many areas. The world’s first bread was found there as well as some of the earliest weavings. Some of the world’s oldest wooden artifacts, wall paints and paintings were found there.

The inhabitants of Catalhoyuk lived in mud-brick and timber houses built around courtyards. The village had no streets or alleyways. Houses were packed so close together people entered their houses through their roofs and often went from place to place via the roofs, which were made of wood and reeds plastered with mud and often reached by ladders and stairways. Bone tools for sewing and weaving have been found at Çatalhöyük.

Prehistoric games include senet, an Egyptian game and Mancala, which originated in Jordan. According to Archaeology magazine: Experts were stunned to find evidence that Bronze Age inhabitants of Tel Megiddo and Tel Erani in present-day Israel had access to exotic foodstuffs from the Far East. Trace amounts of turmeric, soybeans, and bananas were detected in the dental plaque of people who lived in the Levant 3,700 years ago. This is the earliest evidence of these products found outside southern Asia and demonstrates that trade routes between Asia and the Mediterranean date back centuries earlier than previously thought. [Source: Archaeology magazine, March-April 2021]

See Separate Article: LIFE AND CULTURE AT CATALHOYUK, WORLD'S OLDEST TOWN factsanddetails.com ; CANAANITE LIFE: TOOLS, EVERYDAY ITEMS AND MONEY africame.factsanddetails.com ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ritual and Domestic Life in Prehistoric Europe” by Richard Bradley Amazon.com;

“Foragers and Farmers: Population Interaction and Agricultural Expansion in Prehistoric Europe” by Susan A. Gregg (1988) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Textiles” by Elizabeth Wayland Barber (1991) Amazon.com;

“Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years” by Elizabeth Wayland Barber (1994) Amazon.com;

“Moving on in Neolithic Studies: Understanding Mobile Lives” (Neolithic Studies Group by Jim Leary and Thomas Kador (2016) Amazon.com;

“Tracking the Neolithic House in Europe: Sedentism, Architecture and Practice”by Daniela Hofmann, et al. (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Palaeolithic Societies of Europe” (Cambridge World Archaeology)

Clive Gamble Amazon.com;

“Neolithic Houses in Northwest Europe and beyond” by Timothy Darvill and Julian Thomas (2002) Amazon.com;

“A Social Archaeology of Households in Neolithic Greece: An Anthropological Approach” (Cambridge Studies in Archaeology) Stella G. Souvatzi Amazon.com;

“Life in Neolithic Farming Communities: Social Organization, Identity, and Differentiation” by Ian Kuijt (2006) Amazon.com;

Monumentalising Life in the Neolithic: Narratives of Continuity and Change

by Anne Birgitte Gebaer, Lasse Sørensen, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

“Stone Mirror: a Novel of the Neolithic” by Rob Swigart (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Stonehenge People: An Exploration of Life in Neolithic Britain 4700-2000 BC”

by Rodney Castleden (2002) Amazon.com;

“Neolithic Life and Death in the Yorkshire Dales (British)” (2024) by Deborah Hallam Amazon.com;

“The Evolution of Paleolithic Technologies (Routledge Studies in Archaeology)”

by Steven L. Kuhn Amazon.com;

“Culinary Technology of the Ancient Near East From the Neolithic to the Early Roman Period” by Jill L. Baker (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Origins of Cooking: Palaeolithic and Neolithic Cooking”

by Ferran Adrià (2021) Amazon.com;

“Hunting and Fishing in the Neolithic and Eneolithic: Weapons, Techniques and Prey”

by Christoforos Arampatzis and Selena Vitezovic (2024) Amazon.com;

“Dental Microwear in Natufian Hunter-Gatherers and Pre-Pottery Neolithic Agriculturalists from Northern Isreal” by Patrick Mahoney Amazon.com;

“Fisher-Hunters and Neolithic Pastoralists in East Turkana, Kenya” by John Webster Barthelme (1985) Amazon.com;

First Homes and Furniture

The first houses were thought to be windbreaks made of animals skins stretched over a frame. There is evidence that “Homo Erectus” constructed 50-foot-long branch huts with stone slabs or animal skins for floors. A 476,000-year-old wooden structure was unearthed in Zambia.

The oldest recognized buildings in the world are twelve 400,000-year-old huts found in Nice, France in 1960. Uncovered by an excavator preparing to build a new house, the oval shelters ranged from 26 feet to 49 feet in length and were between 13 feet and 20 feet wide. They were built of 3-inch in diameter stakes and braced by a ring of stones. Longer poles were set around the perimeter as supports. The huts had hearths and pebble-lined pits and were defined by stake holes.

Dalya Alberge wrote in The Telegraph: “Archaeological evidence does not reveal how our Neolithic ancestors decorated their interiors, but Mrs Walton argues that they must have been as aesthetically sensitive to their surroundings as we are today. “If you look at other artefacts that you find in the archaeological record, there are little carved figurines and pieces of woven material," she said. "It’s really obvious that these people didn’t just subsist. They lived and thrived and were creative and artistic.” [Source: Dalya Alberge, The Telegraph, April 18, 2021]

“Whether Stone Age man had furniture is unclear. “Certainly there’s evidence in other parts of the world that they had clay or earth platforms to sit on," Mrs Walton said. "But the geology of where we were wouldn’t necessarily have supported that. So we’ve built some benches… Sometimes we do early Neolithic peoples a disservice by thinking that they sat on the ground on a heap of leaves.”

See Separate Article: EARLIEST HOUSES, BUILDINGS, POSSESSIONS AND WOODEN STRUCTURES factsanddetails.com ; CANAANITE LIFE: TOOLS, EVERYDAY ITEMS AND MONEY africame.factsanddetails.com

10,000-Year-Old House in Israel

Canaanite House

In 2013, a construction crew working to expand Israel's Highway uncovered artifacts spanning thousands of years of ancient history, including the remains of a 10,000-year-old house. Archaeologists opened up several trenches in Eshtaol along Israel's Highway 38, were the artifacts were found and a crew with the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) went to work excavating them. [Source: Megan Gannon published November 26, 2013]

The building contained a standing stone (also called mazzeva), which is thought have served a religious function. "This is the first time that such an ancient structure has been discovered in the Judean Shephelah," archaeologists with the IAA said, referring to the plains west of Jerusalem. A typical jar of the early Bronze Age was discovered buried beneath the floor of a building. Eshtaol is located about 25 kilometers (15 miles) west of Jerusalem.

Megan Gannon wrote in Live Science: The building seems to have undergone a number of renovations and represents a time when humans were first starting to live in permanent settlements rather than constantly migrating in search of food, the researchers said. Near this house, the team found a cluster of abandoned flint and limestone axes. "Here we have evidence of man's transition to permanent dwellings and that in fact is the beginning of the domestication of animals and plants; instead of searching out wild sheep, ancient man started raising them near the house," the archaeologists said in a statement.

The excavators also say they found the remains of a possible "cultic" temple that's more than 6,000 years old. The researchers think this structure, built in the second half of the fifth millennium B.C., was used for ritual purposes, because it contains a heavy, 4-foot-tall (1.3 meters) standing stone that is smoothed on all six of its sides and was erected facing east.

"The large excavation affords us a broad picture of the progression and development of the society in the settlement throughout the ages," said Amir Golani, one of the excavation directors for the IAA. Golani added there is evidence at Eshtaol of the rural society making the transition to an urban one during the early Bronze Age, 5,000 years ago. "We can see distinctly a settlement that gradually became planned, which included alleys and buildings that were extremely impressive from the standpoint of their size and the manner of their construction," Golani explained in a statement. "We can clearly trace the urban planning and see the guiding hand of the settlement's leadership that chose to regulate the construction in the crowded regions in the center of the settlement and allowed less planning along its periphery."

3800-Year-Old Bronze Age Jug with a Person at the Top

An 18-centimeter (7-inch) -high Bronze Age jug dated to around 1800 B.C. was found in Yehud, Israel Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: “This small jug, which was found in pieces and has now been completely restored, is, in and of itself, neither rare nor especially informative. In fact, it is very typical for the period. But what makes it distinctive, and thus so revealing, is the unique figure of a person perched on top. It seems, says excavation director Gilad Itach of the Israel Antiquities Authority, that the vessel was made and then the figure was added — when, or whether by the same potter or a new artist, is unknown. But why take an ordinary pot and add such an evocative decoration? [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2017]

According to Itach, it’s likely that the jug, which was discovered among other pottery, metal objects, including daggers, arrowheads, and an ax head, and bones belonging to a sheep and likely a donkey, was buried in honor of an important member of the ancient community. “It’s customary to believe that the objects that were interred alongside an individual continued with them into the next world,” says Itach. Thus the little pot, at first mundane and familiar, becomes a distinctive marker of a person’s individuality and place in society even after they are long gone.

Food in Neolithic-Bronze-Age North Africa and the Middle East

Research published in April 2024 in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution on a the Iberomaurusians, hunter-gatherers who buried their dead in Taforalt cave in what’s now Morocco between 13,000 and 15,000 years ago, adds to evidence that modern humans living at that time mainly had a plant-based, rather than meat-based diet.. Scientists determined that the perhistoric Moroccans ate mainly plants by analyzing chemical signatures preserved in bones and teeth belonging to at least seven different Iberomaurusian. [Source: Katie Hunt, CNN, April 30, 2024]

According to Live Science report, an examination of the bones of lizards and snakes recovered from el-Wad Terrace, a cave near Mount Carmel in northern Israel, indicates that reptiles such as the legless European glass lizard and the large whip snake were eaten by members of the Natufian culture at the site between 15,000 and 11,500 years ago. Archaeology magazine reported: The lizard and snake bones made up about one-third of the animal bones in the cave. Ma’ayan Lev of the University of Haifa said that finding butchery marks on such small bones can be difficult, especially when they have been weathered over a long period of time. Lev and her colleagues therefore experimented with the bones of modern lizards and snakes to identify signs of erosion, burning, trampling, and digestion by birds of prey, and then compared those marks with marks on the ancient remains. [Source: Archaeology.org, June 29, 2020]

In 2018, it was reportedly that tiny pieces of bread were found in fireplaces used by hunter-gatherers 14,000 years ago, predating agriculture by thousands of years. Nicola Davis wrote in The Guardian: Charred crumbs found in a pair of ancient fireplaces have been identified as the earliest examples of bread, suggesting it was being prepared long before the dawn of agriculture. The remains – tiny lumps a few millimetres in size – were discovered by archaeologists at a site in the Black Desert in north-east Jordan. Using radiocarbon-dating of charred plant materials found within the hearths, the team found the fireplaces were used just over 14,000 years ago. [Source: Nicola Davis, The Guardian July 16 2018]

See Separate Article: FOOD IN NEOLITHIC-BRONZE-AGE NORTH AFRICA AND THE MIDDLE EAST factsanddetails.com ; CANAANITE FOOD, DRINK, DRUGS, CLOTHES, JEWELRY africame.factsanddetails.com

Earliest Clothes and Shoes

5,500-year-old Shoes from Areni Cave in Armenia

The oldest known cloth is a 3-by-1½-inch, 9000-year-old piece of linen found in southeastern Turkey at an archaeological site known as Cayonu, near the headwaters of the Tigris River. Linen is made from flax The cloth was partly fossilized. It was found wrapped around an antler, which preserved and fossilized the cloth with calcium. If the antler hadn't been present the cloth would have deteriorated within a century. [Source: John Noble Wilford, Science Section, New York Times July 13, 1992]

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine,“Vividly colored red and blue fragments of wool discovered at a copper mining site in southern Israel’s Timna Valley are offering new insights into the social standing of metalworkers who lived in the remote area. The fragments, which have been radiocarbon dated to 3,000 years ago, are the earliest known examples of textiles treated with plant-based dyes in the Levant. But the plants used to make the dyes — the madder plant for red and most likely the woad plant for blue — could not have been grown in the arid Timna Valley. Nor was there enough water available locally to raise the livestock necessary to provide wool or to dye the fabric. The textiles must, therefore, have been produced elsewhere. According to Naama Sukinek of the Israel Antiquities Authority, the discovery suggests that at least some of the metalworkers at Timna had the resources to purchase this imported cloth. Says Sukinek, “Our finding indicates that the society in Timna included an upper class that had access to expensive and prestigious textiles.” [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2017]

Mark Stoneking of the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig calculated that our human ancestors began wearing clothes about 114,000 years ago based on comparing the DNA of head lice, which have been around millions of years, and body lice (which are misnamed as they appear on clothing rather than the body), which are a relatively new species. His reasoning goes that a new species evolves when there is a new environment (in this case clothing for the body lice) and if he could figure when body lice branched off from head lice (which he did using by comparing the DNA of the two species) he could figure out when early man first wore clothes.

Thirty-five shoes between 8,000 and 5,000 years have been found in a cave along the Missouri River in Calloway County, Missouri since 1955. Made mostly from rattlesnake master, a tough, spiny-edged yucca-like plant, the shoes come in surprising variety of styles. There are slip ons and tie up varieties. Some are insulated with grass. Some have rounded toes and round-cupped heels. Some have double thick soles and slingback heels. Other are worn out. [Source: Nicholas Wade, New York Times, July 7, 1998]

The oldest known leather shoe — a 5,500-year-old leather moccasin — was found in was found in a cave near the village of Areni, Armenia. The 24.5-centimeter-long, 7.6- to-10-centimeter-wide covered piece of footwear was made of an old piece of leather. It had laces and was sawed to fit around the wearer’s foot. Announced in June 2010, the discovery was made near the Armenian-Turkish-Iranian borders by a team from University College Cro in Vayotz Dzor province

See Separate Article: EARLIEST CLOTHES AND SHOES factsanddetails.com ; CANAANITE FOOD, DRINK, DRUGS, CLOTHES, JEWELRY africame.factsanddetails.com

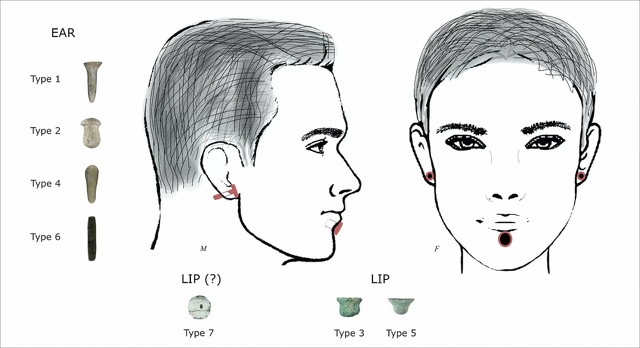

Evidence of Ear and Mouth Piercing at 11,000-Year-Old Burial in Turkey

In March 2024, in an article in the journal Antiquity, archaeologists in Turkey said that stone ornaments found around the mouths and ears of skeletons at an 11,000-year-old burial site of Boncuklu Tarla in southeast Turkey prove that humans have been piercing their bodies since prehistoric times and were thus concerned about their appearance. Although small, thin and pointed stones have been found at several sites in the Fertile Crescent, which includes parts of modern-day Turkey and Iraq, and which is where ancient humans settled to farm, it was not known what they were used for — until now. "None of them have ever been found on the bodies in their original locations," said Emma Louise Baysal, a professor of archaeology at Ankara University, who co-authored an article on the ornaments. [Source: Ece Toksabay, Reuters, March 20, 2024]

Reuters reported: “At the Boncuklu Tarla site, "we have them all on the skeletons very close to the ear holes, to the lips," she said, allowing experts to conclude for the first time they would definitely be used as piercings. Some wear on the lower teeth of the skulls also showed that the individuals would have had lower lip piercings when alive. "I think it shows we share similar concerns with the way that we look and that these people were also thinking hard about how they presented themselves to the world," she said.

The site was established around 11,000 years ago by a group of hunter-gatherers, who gradually settled. Excavations are continuing at Boncuklu Tarla (Beaded Field), named after local farmers found thousands of beads, and where over 100,000 artefacts have been unearthed to date. The excavations not only show how early societies formed but also highlight striking similarities between modern humans and Neolithic people, highlighting lives we can empathise with, Baysal said. "When you put on ornaments, particularly on your face, you can't see them, other people can see them. And you're projecting an image to other people.It shows that we are, in many ways very similar."

Mindy Weisberger of CNN wrote: Dental wear on the lower incisors of the remainsresembled known wear patterns caused by abrasion from a type of ornament called a labret, often worn below the lower lip. People of all ages were buried at Boncuklu Tarla, but the newly described ornaments were found only near the remains of adults. This suggests that such adornments were not worn by children, and acquiring these piercings may have marked coming-of-age rituals within social groups, according to the study. Though children were buried with pendants and beads, none had ear ornaments or labrets near their heads, necks or chests, indicating that facial piercings were reserved for adults, the researchers concluded. “It’s probably something associated with being grown-up,” Baysal said. “Maybe a kind of social status associated with age, or a particular role in society.” [Source: Mindy Weisberger, CNN, March 12, 2024]

There are some other types of evidence for coming-of-age rituals in the Neolithic, such as burials that arrange the body with certain artifacts “or the placement of the deceased in particular locations prescribed for a particular age group,” said anthropological archaeologist Dusan Boric, an associate professor at Sapienza Università di Roma in Italy. “But I cannot think of many other examples as convincing as this one,” said Boric, who was not involved in the study.

Types of Ornaments and Body Piercings Found the at 11,000-Year-Old Burial in Turkey

Hunter-gatherers occupied Boncuklu Tarla from around 10,300 B.C. to 7100 B.C., as people began to shift away from a nomadic lifestyle and form settlements. Mindy Weisberger of CNN wrote: The site was first excavated in 2012 and has since yielded a bounty of ornamental objects from the Neolithic period, with approximately 100,000 decorative artifacts found to date — a staggering number, said study coauthor Dr. Emma L. Baysal, an associate professor of archaeology at Ankara University in Turkey. [Source: Mindy Weisberger, CNN, March 12, 2024]

“The sheer quantity is unbelievable. This is a site of people who just adore adornment, more than at any other site,” Baysal told CNN. “They had masses and masses of beads and they made complicated things out of beads,” including necklaces, bracelets, animal-shaped pendants and decorations that could be sewn onto clothing, Baysal said. They also crafted ornaments for ear and lip piercings. Labrets, which are still worn in some cultures in Amazonia and Africa, come in a variety of forms: rounded, oblong and disc-shaped. Some are long and thin, but most have one end that is wider and flattened, and they vary in diameter and width.

Scientists identified 85 objects from Boncuklu Tarla burials as ornaments worn in piercings, made of materials such as flint, limestone, copper and obsidian. The researchers classified the labrets into seven types, based on shape — all measured at least 0.3 inches (7 millimeters) in diameter, and the longest was just over 2 inches (50 millimeters) in length.

Ornaments described as Type 1 had long shafts and a “nail-like appearance” and were probably worn “inserted into the flesh or cartilage of the ear,” according to the study. Elongated Types 2, 4 and 6 were also thought to be ear ornaments. By comparison, Types 3 and 5 labrets had shorter, more bulbous shafts — better-suited for lip wear. Type 7, a flattened disc, was also thought to be a kind of labret.

Some of the labrets had been dislodged from their original positions in the graves, possibly by rodents, though they were still near the head and neck area of the human remains. Other pieces were still “lodged in position on the upper or lower surface of the skull or under the lower jaw,” the study authors reported.

Ancient Tattoos

Aaron Deter-Wolf, a prehistoric archaeologist at the Tennessee Division of Archaeology and a leading researcher in the archaeology of tattooing, told the New York Times that there has been a lot of resistance to accepting tattooing as an art form and as a topic worthy of study. “Even when the 5,300-year-old body of Ötzi the Iceman was recovered from the Italian Alps in 1991 bearing visible tattoos, some news reports at the time suggested the markings were evidence that Ötzi was “probably a criminal,” Deter-Wolf said. “It was very biased.”

Krista Langlois wrote in the New York Times: But as tattooing has become more mainstream in Western culture, Deter-Wolf and other scientists have begun to examine preserved tattoos and artifacts for insights into how past people lived and what they believed. A 2019 investigation into Ötzi’s 61 tattoos, for example, paints a picture of life in Copper Age Europe. The dots and dashes on the mummy’s skin correspond with common acupuncture points, suggesting that people had a sophisticated understanding of the human body and may have used tattooings to ease physical ailments like joint pain. In Egypt, Anne Austin, an archaeologist at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, has found dozens of tattoos on female mummies, including hieroglyphics suggesting the tattoos were associated with goddess worship and healing. This interpretation challenges 20th-century male scholars’ theories that female tattoos were simply erotic decorations or were reserved for prostitutes. [Source: Krista Langlois, New York Times, July 6, 2021]

“The scientific study of tattooed mummies also inspires practitioners like Elle Festin, a tattooist of Filipino heritage living in California. As co-founder of Mark of the Four Waves, a global community of nearly 500 members of the Filipino diaspora united through tattooing, Festin has spent more than two decades studying Filipino tribal tattoos and using them to help those living outside the Philippines reconnect with their homeland. One of his sources is the “fire mummies” — people from the Ibaloi and Kankanaey tribes whose heavily tattooed bodies were preserved by slow-burning fire centuries ago.

“If clients are descended from a tribe that made fire mummies, Festin will use the mummies’ tattoos as a framework for designing their own tattoos. (He and other tattooists say that only people with ancestral ties to a culture should receive that culture’s tattoos.) So far, 20 people have received fire mummy tattoos. “For other clients, Festin gets more creative, adapting age-old patterns to modern lives. For a pilot, he says, “I would put a mountain below, a frigate bird on top of it and the patterns for lightning and wind around it.”

“Yet while mummies offer the most conclusive evidence of how and where past people inked their bodies, they are relatively rare in the archaeological record. More common — and thus more helpful for scientists tracking the footprint of tattooing — are artifacts like tattoo needles made of bone, shell, cactus spines or other materials. “To show that such tools were used for tattooing, rather than stitching leather or clothing, archaeologists such as Deter-Wolf replicate the tools, use them to tattoo either pig skin or their own bodies, then examine the replicas under high-powered microscopes. If the tiny wear patterns made by repeatedly piercing skin match those on the original tools, archaeologists can conclude that the original artifacts were indeed used for tattooing.

See Separate Article:

OTZI, THE ICEMAN'S CLOTHES, SHOES AND TATTOOS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OTZI, THE ICEMAN: HIS HOME, BACKGROUND, DNA AND TOOLS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OTZI, THE ICEMAN'S HEALTH, DIET AND DISEASES europe.factsanddetails.com

Neolithic Jewelry

According to Archaeology magazine: Humans have been wearing animal teeth as personal adornments for millennia. Some 8,500 years ago, people in the village of Catalhoyuk began fashioning pendants from parts of their deceased human brethren. Two human teeth recently found at the site had been carefully drilled so that they could be worn on a string. This is the oldest known evidence of this practice in the Near East. Wearing the teeth was likely not an everyday habit, but instead may have had special symbolic and ritual significance. [Source: Daniel Weiss Archaeology magazine, March -April 2020]

Using a technique for analyzing friction in industrial equipment, a group of French and Turkish scientists have unraveled the process that was used approximately 10,000 years ago to make a highly polished obsidian bracelet. The team examined a bracelet fragment from Aşıklı Höyük in Turkey at different levels of magnification and saw evidence of three stages of production — pecking, grinding, and polishing. Striations on the bracelet indicate that a mechanical device may have been used to achieve its regularized shape and glossy finish. It is the earliest evidence of such a sophisticated stone-working technique. [Source: Zach Zorich Archaeology magazine, Volume 65 Number 3, May-June 2012]

4,000-Year-Old Cosmetic From Iran — World’s Oldest Lipstick?

In February 2024, researchers reported in the journal Scientific Reports that a small stone vial found in southeastern Iran contained a red cosmetic that was likely used as a lip coloring nearly 4,000 years ago. The discovery is “probably the earliest” example of lipstick to be scientifically documented and analyzed, the scientists said. More than 80 percent of the analyzed sample was made up of minerals that produce a deep red color — primarily hematite. The mixture also contained manganite and braunite, which have dark hues, as well as traces of other minerals and waxy substances made from vegetables and other organic substances. “Both the intensity of the red coloring minerals and the waxy substances are, surprisingly enough, fully compatible with recipes for contemporary lipsticks,” the study authors noted. [Source: Katie Hunt, CNN, March 19, 2024]

Katie Hunt of CNN wrote: It’s not possible to exclude the possibility the cosmetic was used in other ways, say, as a blusher, according to lead study author Massimo Vidale, an archaeologist at the University of Padua’s Department of Cultural Heritage in Italy. But he said the homogenous, deep red color, the compounds used and the shape of the vial “suggested to us it was used on lips.” It’s one of the first examples of an ancient, red-colored cosmetic to be studied, he said, although it wasn’t clear why cosmetic preparations resembling lipstick were uncommon in the archaeological record.“We have no idea, for the moment. The deep red color we found is the first one we met, while several lighter-colored foundations and eye shadows had been identified before,” he said.

The use of hematite — crushed red ocher — had been documented on stone cosmetic palettes from the late Neolithic, as well as in ancient Egyptian cosmetic vessels, according to Joann Fletcher, a professor in the University of York’s department of archaeology. Whether the vial from Iran was the earliest lipstick, “all comes down to what this new discovery was actually used for,” she said. “It is possible the contents of the vial were used as a lip colour. But they could also have been applied to give colour to the cheeks, or for some other purpose, even if the vial looks like a modern lipstick tube,” said Fletcher, who was not involved in the research.

It is “very plausible” the artifact was a lipstick, said Laurence Totelin, a professor of ancient history in the School of History, Archaeology and Religion at Cardiff University specializing in Greek and Roman science, technology, and medicine. “As the authors point out, the recipe is not dissimilar to a modern one. The deep red colour is also what we would expect for lip make up,” said Totelin. “That said, the ingredients are also regularly found in the preparation of ancient medicines, and the vial has a shape that is not inconsistent with a pharmaceutical use,” Totelin said.

The preparation contained quartz particles, from ground sand or crystal, perhaps added, the study suggested, as a ”shimmery-glittering agent” — although it was possible they came from the inside of the vial itself, which was finely crafted from a greenish stone called chlorite. It’s also not clear what the original consistency of the cosmetic would have been — a fluid or more solid, Vidale said.

“The vial’s slender shape and limited thickness suggest that it could have been conveniently held in one hand together with the handle of a copper/bronze mirror, leaving the other hand free to use a brush or another kind of applicator,” the study authors wrote,citing an ancient Egyptian papyrus dated to the 12th century BC that depicts a young woman painting her lips in such a way as an example.

The artifact was among thousands of items unearthed from Bronze Age tombs and graves in the Jiroft region of Iran. The graves — part of an ancient kingdom known as Marhasi — were exposed and dislodged in 2001 when a river flooded, after which their precious contents were looted and sold by locals. Many stone and copper items, including the vial, were subsequently recovered by Iranian security forces. The vial is kept in the National Archaeological Museum of Jiroft, where the team took samples.

2,700-Year-Old Luxury Toilet Found in Jerusalem

In October 2021, Israeli archaeologists announced that they had found a rare ancient toilet in Jerusalem that was 2,700 years old, when only the rich had private bathrooms. Associated Press reported: The Israeli Antiquities Authority said the smooth, carved limestone toilet was found in a rectangular cabin that was part of a sprawling mansion overlooking what is now the Old City. It was designed for comfortable sitting, with a deep septic tank dug underneath. “A private toilet cubicle was very rare in antiquity, and only a few were found to date,” said Yaakov Billig, the director of the excavation. “Only the rich could afford toilets.” [Source: Associated Press, October 5, 2021]

The toilet had a seat and a hole in the middle, "so whoever is sitting there would be very comfortable," Billig said. The toilet, which was situated above a septic tank, was found inside a rectangular cabin that would have served as the ancient bathroom. The bathroom also held 30 to 40 bowls, Billig told Haaretz. He speculated that the bowls may have been used to hold air freshener, in the form of a pleasant-smelling oil or incense. [Source: Yasemin Saplakoglu, Live Science, October 8, 2021]

Live Science reported: Within the settlement, the archaeologists also discovered ornamented stones that were carved for various purposes such as for stone capitals — small detailed pieces of stone that form the tops of columns — or window frames and railings, Billig said in the video. Nearby the toilet, Billig and his team discovered evidence of a garden filled with ornamental trees, fruit trees and aquatic plants.All of these relics help the researchers recreate the picture of an "extensive and lush" mansion, according to the statement. Archaeologists first discovered the remains of the ancient mansion on the Armon Hanatziv promenade in Jerusalem two years ago, and excavations are continuing. It was "probably a palace of one of the kings of the Judean Kingdom," Billig said in the video. The world's oldest toilet was discovered in the ruins of Tell Asmar (Eshuan'na) in Iraq. It was dated to around 4,000 years ago.

At the time of the toilet Jerusalem was a busy political and religious center in the Assyrian empire and home to between 8,000 and 25,000 people. “While they did have toilets with cesspits across the region by the Iron Age, they were relatively rare and often only made for the elite,” the 2023 study mentioned below said. “Towns were not planned and built with a sewerage network, flushing toilets had yet to be invented and the population had no understanding of existence of microorganisms and how they can be spread.”

Feces from 2,500-Year-Old Toilets in Jerusalem Indicate People Had Dysentery

Users of 2,500-year-old toilets in Jerusalem were not very healthy according to an analysis of feces found in the toilets. CNN reported: Researchers found traces of dysentery-causing parasites in material excavated from the cesspits below the two stone toilets that would have belonged to elite households in the city. It’s the earliest known evidence of a disease called Giardia duodenalis, although the infection, which causes diarrhea, abdominal cramps and weight loss, had previously been identified in Roman-era Turkey and in medieval Israel. [Source: CNN, May 26, 2023]

“Dysentery is spread by faeces contaminating drinking water or food, and we suspected it could have been a big problem in early cities of the ancient Near East due to over-crowding, heat and flies, and limited water available in the summer,” said Dr. Piers Mitchell, lead author of the study that published in the scientific journal Parasitology and an honorary fellow at the University of Cambridge’s Department of Archaeology, in a statement. Most of those who die from dysentery caused by Giardia are children, and chronic infection in kids can lead to stunted growth, impaired cognitive function and failure to thrive.

The ancient Middle East was where some of the first cities were formed. People often lived together, sometimes with domesticate animals present. Cities such as Jerusalem likely would have been hot spots for disease outbreaks, and illnesses would have spread easily by traders and during military expeditions, according to the study.

Ancient poop is a rich source of information for archaeologists and has revealed an Iron Age appetite for blue cheese, a mystery population on the Faroe Islands and the discovery that the builders of Stonehenge feasted on the internal organs of cattle. Archaeologists excavating the latrines took samples from sediment in the cesspit beneath each toilet seat. They found one seat south of Jerusalem in the neighborhood of Armon ha-Natziv at a mansion excavated in 2019. It likely dates from the days of King Manasseh, who ruled for 50 years in the mid-seventh century B.C. Made of limestone, the toilet has a large central hole for defecating and an adjacent hole likely for male urination. The other toilet seat studied, similar in design, was excavated in the Old City of Jerusalem at a seven-room building known as the House of Ahiel, which would have been home to an upper-class family at the time.

The eggs of four types of intestinal parasites — tapeworm, pinworm, roundworm and whipworm — previously had been identified in the cesspit sediment. But the microorganisms that cause dysentery are fragile and extremely hard to detect, according to the new study. To overcome this problem, the team used a biomolecular technique called ELISA in which antibodies bind onto proteins uniquely produced by particular species of single-celled organisms. The researchers tested for Entamoeba, Giardia and Cryptosporidium: three parasitic microorganisms that are among the most common causes of diarrhea in humans — and behind outbreaks of dysentery. Tests for Entamoeba and Cryptosporidium were negative, but those for Giardia were repeatedly positive.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except piercings from Anatolian Archaeology, Otzi from South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, lipstick from M. Vidale, F. Zorzi/Scientific Reports, jug from Archaeology magazine

Text Sources: Live Science, Wikipedia, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024