Home | Category: Late Stone Age and Copper and Bronze Age / First Cities, Archaeology and Early Signs of Civilization

FOOD IN NEOLITHIC-BRONZE AGE ISRAEL

Neolithic-style bread oven

According to Live Science report, an examination of the bones of lizards and snakes recovered from el-Wad Terrace, a cave near Mount Carmel in northern Israel, indicates that reptiles such as the legless European glass lizard and the large whip snake were eaten by members of the Natufian culture at the site between 15,000 and 11,500 years ago. Archaeology magazine reported: The lizard and snake bones made up about one-third of the animal bones in the cave. Ma’ayan Lev of the University of Haifa said that finding butchery marks on such small bones can be difficult, especially when they have been weathered over a long period of time. Lev and her colleagues therefore experimented with the bones of modern lizards and snakes to identify signs of erosion, burning, trampling, and digestion by birds of prey, and then compared those marks with marks on the ancient remains. [Source: Archaeology.org, June 29, 2020]

“The most surprising find was the butchery marks on several large whip snake vertebrae,” Lev said, adding that the marks were found in identical locations of different bones. These animals were likely eaten by humans, Lev said. The study also suggests the eastern Montpellier snake, the common viper, and other smaller lizards and snakes whose remains were found in the cave were likely eaten by raptors or died of other causes. To read about human consumption of a snake in southwest Texas 1,500 years ago, go to “Snake Snack.”

A study of Stone Age hunter-gatherers in Peru published in January 2024 involving the remains of 24 early humans from two burial sites dated from 9,000 to 6,500 years ago — revealed that ancient diets in the Andes were composed of 80 percent plant matter and 20 percent meat. [Source: Katie Hunt, CNN, April 30, 2024]

According to Archaeology magazine: A unique 7,000-year-old ceramic vessel from the site of Tel Tsaf in the Jordan Valley of Israel may have been used in early food rituals associated with grain storage. The site contains numerous silos that are believed to be the oldest large-scale storage containers that existed in the region at the time. Experts think the unusual pot, which is topped with red-painted clay balls and resembles a miniature silo, was used during ceremonies that preceded the placement or removal of grain. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2018]

Experts were stunned to find evidence that Bronze Age inhabitants of Tel Megiddo and Tel Erani in Israel had access to exotic foodstuffs from the Far East. Trace amounts of turmeric, soybeans, and bananas were detected in the dental plaque of people who lived in the Levant 3,700 years ago. This is the earliest evidence of these products found outside southern Asia and demonstrates that trade routes between Asia and the Mediterranean date back centuries earlier than previously thought. [Source: Archaeology magazine, March-April 2021]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Origins of Cooking: Palaeolithic and Neolithic Cooking”

by Ferran Adrià (2021) Amazon.com;

“Culinary Technology of the Ancient Near East From the Neolithic to the Early Roman Period” by Jill L. Baker (2014) Amazon.com;

“Hunting and Fishing in the Neolithic and Eneolithic: Weapons, Techniques and Prey”

by Christoforos Arampatzis and Selena Vitezovic (2024) Amazon.com;

“Projectile Points, Hunting and Identity at Neolithic Çatalhöyük, Turkey”

by Lilian Dogiama (2023) Amazon.com;

“Dental Microwear in Natufian Hunter-Gatherers and Pre-Pottery Neolithic Agriculturalists from Northern Isreal” by Patrick Mahoney Amazon.com;

“Fisher-Hunters and Neolithic Pastoralists in East Turkana, Kenya” by John Webster Barthelme (1985) Amazon.com;

“Plant Foods of Greece: A Culinary Journey to the Neolithic and Bronze Ages” by Soultana Maria Valamoti (2023) Amazon.com;

“Meat-Eating and Human Evolution” by Craig B. Stanford, Henry T. Bunn Amazon.com;

“The Evolution of Hominin Diets: Integrating Approaches to the Study of Palaeolithic Subsistence” by Jean-Jacques Hublin, Michael P. Richards, Editors (2009) Amazon.com;

“Modern Origins: A North African Perspective by Jean-Jacques Hublin (2012) Amazon.com;

“Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human” by Richard Wrangham Amazon.com;

“Evolution's Bite: A Story of Teeth, Diet, and Human Origins” by Peter Ungar (2017) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Cookery, Recipes and History,” by Jane Renfrew (English Heritage, 2006) Amazon.com

“Arrowpoints, Spearheads, and Knives of Prehistoric Times” by Thomas Wilson (2022) Amazon.com

“A View to a Kill: Investigating Middle Palaeolithic Subsistence Using an Optimal Foraging Perspective” (2008) by G. L. Dusseldorp Amazon.com

“Evolution of the Human Diet: The Known, the Unknown, and the Unknowable” by Peter S. Ungar Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

Plant-Based Diet of Modern Humans in Morocco 14,000 Years Ago

Research published in April 2024 in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution on a the Iberomaurusians, hunter-gatherers who buried their dead in Taforalt cave in what’s now Morocco between 13,000 and 15,000 years ago, adds to evidence that modern humans living at that time mainly had a plant-based, rather than meat-based diet.. Scientists determined that the perhistoric Moroccans ate mainly plants by analyzing chemical signatures preserved in bones and teeth belonging to at least seven different Iberomaurusian. [Source: Katie Hunt, CNN, April 30, 2024]

Making bread the Bedouin way

“Our analysis showed that these hunter-gatherer groups, they included an important amount of plant matter, wild plants to their diet, which changed our understanding of the diet of pre-agricultural populations,” said lead study author Zineb Moubtahij, a doctoral student at Géosciences Environnement Toulouse, a research institute in France, and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

According to CNN: The share of plant resources as a source of dietary protein in the humans whose remains were studied was similar to that seen in early farmers from the Levant, the present-day Eastern Mediterranean countries where plant domestication and farming were first documented. However, the Iberomaurusians weren’t strict vegetarians, the study noted. Cut marks on the remains of Barbary sheep and gazelles, as well as ancient horselike and cowlike mammals, suggested that some animals had been butchered and processed for food. The increased reliance on plant food was probably driven by several factors — including a wider range of edible plants and perhaps a depletion of large game species, according to the study.

Researchers also spotted a higher number of tooth cavities among the Taforalt specimens than is typically seen with hunter-gatherer remains of that period. The evidence suggested that the Iberomaurusians consumed “fermentable starchy plants” such as wild cereals or acorns, according to the study. coauthor Klervia Jaouen, a researcher at Géosciences Environnement Toulouse said that in the Levant region, archaeologists had documented a similar plant-based diet among another group that practiced a hunting-and-gathering lifestyle just before the development of agriculture, raising questions as to why the transition to farming did not simultaneously occur among the Iberomaurusian population.

The findings raise some intriguing questions about how agriculture spread across different regions and populations. “While not all individuals primarily obtained their proteins from plants at Taforalt, it is unusual to document such a high proportion of plants in the diet of a pre-agricultural population,” said Jaouen. “This is likely the first time such a significant plant-based component in a Paleolithic diet has been documented using isotope techniques,” Jaouen added. The isotope analysis also detected evidence of one case of early weaning, with starchy plant foods introduced into an infant’s diet before its death at between 6 and 12 months old. This contrasts with hunter-gatherer societies where extended breast-feeding periods are the norm due to the limited availability of weaning foods,” according to the study.

Earliest Evidence of Bread: From a 14,000-Year-Old Natufian Site

In 2018, it was reportedly that tiny pieces of bread were found in fireplaces used by hunter-gatherers 14,000 years ago, predating agriculture by thousands of years. Nicola Davis wrote in The Guardian: Charred crumbs found in a pair of ancient fireplaces have been identified as the earliest examples of bread, suggesting it was being prepared long before the dawn of agriculture. The remains – tiny lumps a few millimetres in size – were discovered by archaeologists at a site in the Black Desert in north-east Jordan. Using radiocarbon-dating of charred plant materials found within the hearths, the team found the fireplaces were used just over 14,000 years ago. [Source: Nicola Davis, The Guardian July 16 2018]

“Bread has been seen as a product of agriculturist, settled societies, but our evidence from Jordan now basically predates the onset of plant cultivation … by at least 3,000 years,” said Dr Tobias Richter, co-author of the study from the University of Copenhagen, noting that fully-fledged agriculture in the Levant is believed to have emerged around 8,000 BC. “So bread was being made by hunter-gatherers before they started to cultivate any plants,” he said.

Writing in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Richter and colleagues from Denmark and the UK describe how during excavations between 2012 and 2015 they found the crumbs in the fireplaces of a site used by hunter-gatherers known as Natufians, who foraged for wild grains. Among the remains, the team unearthed small, round tubers of a wetland plant known as club-rush, traces of legumes and plants belonging to the cabbage family, wild cereals including some ground wheat and barley – and 642 small charred lumps.

See Separate Article: NATUFIAN LIFE AND CULTURE (14,500-11,500 YEARS AGO) africame.factsanddetails.com

Did Neolithic People Hunt Leopards and Bears in the Southern Levant?

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Archaeologists rarely unearth the remains of large predators such as leopards, lions, and bears. But University of Haifa archaeologist Ron Shimelmitz and his colleagues wondered if, by looking at a large number of sites over thousands of years, they could identify evidence showing that ancient people hunted these fearsome creatures. The team reviewed reports of animal remains discovered at sites in the southern Levant dating from 25,000 to 2,500 years ago. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2023]

They found that the frequency at which leopard, lion, and bear skeletal remains were found changed over time. Leopard bones were relatively numerous at sites dating to the Neolithic period (9700–4700 B.C.), but were virtually nonexistent in later Copper and Bronze Age (4700–1200 B.C.) settlements, where there were more bear bones and many lion bones. “If these bones were the result of random encounters with predators,” says Shimelmitz, “then you wouldn’t expect to see a pattern.”

The researchers hypothesize that the shift reflects the changing symbolic importance of large predators over time. As people first came together in permanent settlements in the Neolithic period, the solitary, nocturnal leopard, a symbol of the dangerous natural world, may have acquired special significance. Later, as societies grew more complex and social hierarchies developed in the Copper and Bronze Ages, the lion and the bear may have become more important as symbols of authority. The team found that lion head and toe bones were particularly well represented at sites dating to the Bronze Age (3700–1200 B.C.), leading them to speculate that the bones are what was left of pelts. “Wearing pelts allowed people to prolong the symbolic value of the lion hunt for years,” says Shimelmitz.

Feasting in Neolithic Times

Archaeological evidence shows that communally shared meals have long been vital components of human rituals. Professors Natalie Munro and Leore Grosman discovered what they say is the earliest evidence of a ritual feast at a 12,000-year-old archaeological site of Hilazon Tachtit in northern Israel and learned how feasts came to be integral components of modern-day ritual practice. [Source: Natalie Munro, University of Connecticut, phys.org, December 27, 2017]

Natalie Munro wrote: When we first embarked on the excavations at in the late 1990s, we were only hoping to document the activities of the last hunter-gatherers in Israel, at what appeared to be a small campsite. It was only over several seasons of excavation that it slowly became clear to us that this was not a site where people had lived. Rather it was a site for rituals. No houses, fireplaces or cooking areas were recovered. Instead the cave yielded the skeletal remains of at least 28 individuals interred in three pits and two small structures.

Stone Age feast

One of these structures contained the complete skeleton of an older woman, who we interpreted as a shaman based on her special treatment at death. Her grave stood apart due to its fine construction — the walls were plastered with clay and inset with flat stone slabs. Even more remarkable was the eclectic array of animal body parts buried alongside of her. The pelvis of a leopard, the wing tip of an eagle, the skulls of two martens and many other unusual body parts surrounded her skeleton. The butchered remnants of more than 90 tortoises buried in the grave and the leftovers of at least three wild cattle deposited in a second adjacent depression excavated in the cave floor represent the remains of a funeral feast. See Below

Archaeologists have found other sites that show evidence of ritual feasting. Many of these date to the time when humans were beginning to farm. One of the most striking is the site of Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey, dating slightly later than Hilazon Tachtit. It includes multiple large structures adorned with benches and giant stone slab carved with exquisite animal depictions in relief dating to 11-12,000 years ago. Perhaps, these were very early communal buildings. The archaeologists who excavated Göbekli Tepe argue that massive quantities of animal bones associated with the structures represent the remains of feasts.

Twelve thousand years ago humans were still hunter-gatherers, subsisting entirely on wild foods. Nevertheless, these people differed from those who went before — they were sitting on the brink of the transition to agriculture, one of the most significant economic, social and ideological transformations in human history.

Sickle blades and grinding stones used to harvest and process cereal grains are found at Hilazon Tachtit and other contemporary archaeological sites. These findings indicate that these ritual feasts started around the same time that people adopted agriculture. When people began to rely more heavily on wild cereals like wheat and barley, they became increasingly tethered to landscapes that were ever more crowded and began to settle into more permanent communities. In other words, feasting became a part of their life, once they moved away from nomadic life.

These feasts had an important role to play. Adapting to village life after hundreds of millennia on the move was no simple act. Research on modern hunter-gatherer societies shows that closer contact between neighbors dramatically increased social tensions. New solutions to avoid and repair conflict were critical. The simultaneous appearance of feasting, communal structures and specialized ritual sites suggest that humans were seeking to solve this problem by engaging the community in ritual practice. One of the central functions of ritual in these communities was to provide a kind of social glue that bound community members by promoting social cohesion and solidarity. Feasts generate loyalty and commitment to the community’s success. Sharing food is intimate and it builds trust. Communal rituals would have provided a shared sense of identity at a time when social circles were increasing in scale and permanence. They reinforced new ideologies that emerged out of a dramatic reorganization of economic and social life.

See Separate Article: GOBEKLI TEPE: TEMPLE, SETTLEMENT, MEANING, PEOPLE WHO USED IT factsanddetails.com

Feast of Turtles and Steak for 12,000-Year-Old Female Shaman

The world's first known organized feast — or food event of any kind — appears to have been a meal for 35 people that included the meat 71 tortoises and at least three wild cattle held around 12,000 years ago at a burial site in Israel. Jennifer Viegas wrote in Discovery News: “The discovery additionally provides the earliest known compelling evidence for a shaman burial, the apparent reason for the feasting. A shaman is an individual who performs rituals and engages in other practices for healing or divination. In this case, the shaman was a woman. "I wasn't surprised that the shaman was a woman, because women have often taken on shamanistic roles as healers, magicians and spiritual leaders in societies across the globe," lead author Natalie Munro told Discovery News. [Source: Discovery News, Jennifer Viegas, August 30, 2010 ||~||]

“Munro, a University of Connecticut anthropologist, and colleague Leore Grosman of Hebrew University in Jerusalem excavated and studied the shaman's skeleton and associated feasting remains. These were found at the burial site, Hilazon Tachtit cave, located about nine miles west of the Sea of Galilee in Israel. According to the study, published in the latest Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the grave consisted of an oval-shaped basin that was intentionally cut into the cave's floor. "After the oval was excavated, the sides and bottom of the floor were lined with stone slabs lined and plastered with clay brought into the cave from outside," said Munro. ||~||

“The 71 tortoise shells, previously butchered for meat removal, were found situated under, around and on top of the remains of the woman. The woman's skeleton indicates she suffered from deformities that would have possibly made her limp and "given her an unnatural, asymmetrical appearance." A large triangular stone slab was placed over the grave to seal it. Bones from at least three butchered aurochs -- large ancestors of today's domestic cattle -- were unearthed in a nearby hollow. An auroch's tail, a wild boar forearm, a leopard pelvis and two marten skulls were also found. ||~||

“The total amount of meat could have fed 35 people, but it is possible that many more attended the event. "These remains attest to the unique position of this individual within her community and to her special relationship with the animal world," Munro said. Before this discovery, other anthropologists had correctly predicted that early feasting might have occurred just prior to the dawn of agriculture. ||~||

Harvard's Ofer Bar-Yosef, for example, found that fig trees were being domesticated in the Near East about 11,400 years ago, making them the first known domesticated crop. Staples such as wheat, barley and legumes were domesticated in the region roughly a thousand years later. Full-scale agriculture occurred later, about 10,000 years ago. As agriculture began, however, "there was a critical switch in the human mind: from exploiting the earth as it is to actively changing the environment to suit our needs," Bar-Yosef said. Munro agrees and thinks the change could help to explain the advent of communal feasting. "People were coming into contact with each other a lot, and that can create friction," she said. "Before, they could get up and leave when they had problems with the neighbors. Now, these public events served as community-building opportunities, which helped to relieve tensions and solidify social relationships."” ||~||

Desert Kites

Neolithic hunters used “desert kites” to herd, trap and then kill prey. Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Desert kites consist of pairs of rock walls that extend across the landscape, often over several miles, and converge on an enclosure where prey such as gazelles could be herded and then easily dispatched. Ones in Jordan date to the Neolithic period (12,000 to 7,000 years ago). [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, January/February 2023]

Desert kites are dry stone wall structures found in mainly in Southwest Asia (Middle East) but also in North Africa, Central Asia and Arabia. They were first discovered from the air during the 1920s. There are over 6,000 known ones, ranging in size from less than a hundred meters to several kilometres. They typically have a kite shape formed by two convergent "antennae" that run towards an enclosure, all formed by walls of dry stone less than one metre high, but variations exist. Research published in 2022 has shown that pits several metres deep often lie at the margins of enclosures, which have been interpreted as traps and killing pits.[Source: Wikipedia]

Similar structures have been in northern areas, notably under Lake Huron, and were used during the glacial peak of the last Ice Age to hunt reindeer. Recently one was found in the Baltic Sea. They have also been found in Greenland. Dating kites is difficult;various dating methods like radiocarbon dating and optically stimulated luminescence have yielded a wide range of dates. There are a handful of description in old travel reports. Some kites have later archaeological structures bult over them so if that structure can be dated we know at least the desert kite is at least older than the structure, and calculating erosion rates can provide a better date.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ARABIA AND MIDEAST FROM THE AIR: MUSTALIS, DESERT KITES AND FUNERARY AVENUES factsanddetails.com

Çatalhöyük Diet and Food, 10,000 Years Ago

Çatalhöyük (668 kilometers 415 miles southeast of Istanbul) is widely accepted as being the world's oldest village or town. Established around 7500 B.C. , it covered 32 acres and was home to between 3000 to 8000 people. Because of the way of the houses are packed so closely together it is hard to dispute it as being anything other than a village or town. [Sources: Ian Hodder, Natural History magazine, June 2006; Michael Batler, Smithsonian magazine, May 2005; Orrin Shane and Mine Kucuk, Archaeology magazine, March/April 1998]

Analysis of proteins preserved in bowls, pottery and jars at Çatalhöyük has revealed what the people there ate. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, the Freie Universität Berlin and the University of York using this method have provided glimpses of the diet of people living at the site in astonishing scope and detail, determining that vessels from this early farming site contained cereals, legumes, dairy products and meat, in some cases narrowing food items down to specific species. [Source: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, October 3, 2018]

According to the Max Planck Institute: For this study, the researchers analyzed vessel sherds from the West Mound of Çatalhöyük, dating to a narrow timeframe of 5900-5800 B.C. towards the end of the site's occupation. The vessel sherds analyzed came from open bowls and jars, as shown by reconstructions and had calcified residues on the inside surfaces. In this region today, limescale residue on the inside of cooking pots is very common. The researchers used state-of-the-art protein analyses on samples taken from various parts of the ceramics, including the residue deposits, to determine what the vessels held.

In April 2014, archaeologists announced that they had discover what may be oldest known piece of bread at Çatalhöyük — dating back to around 6,600 B.C. The Independent reported: In a new excavation at the site, researchers have uncovered the remains of a building with what appears to be an ancient oven surrounded by wheat, barley, and pea seeds. Archaeologists also found a “spongy” organic residue near the oven with the mark of a finger pressed at its center. The earliest known evidence of fermented bread before this discovery was from ancient Egypt around 1,500 B.C..[Source: Vishwam Sankaran, The Independent, April 17, 2024]

RELATED ARTICLES:

LIFE AND CULTURE AT CATALHOYUK, WORLD'S OLDEST TOWN factsanddetails.com

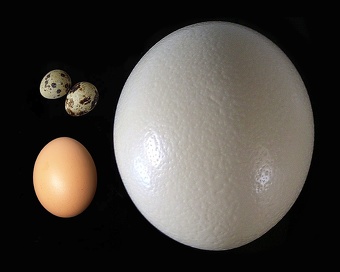

People Enjoyed Ostrich Eggs in Israel 4,000 Years Ago

Eight ostrich eggs believed to more than 4,000 years old were found next to an ancient fire pit at a prehistoric camp site underneath the Nitzana sand-dunes in the Beer Milka area of Israel's Negev desert. One ostrich egg has the same nutritional value as about 25 chicken eggs, Additionally, ostrich eggs were not only consumed as food they also served as funerary vessels, luxury items, material for bears and water carriers in prehistoric times. Some were decorated with engravings or paintings. Excavation director Lauren Davis said archaeologists also unearthed stone tools and pottery shards, but that the eggs were "the truly special find". [Source: BBC, January 12, 2023]

The BBC reported: Wild ostriches were common in the area until the 19th Century. The large flightless birds' eggs have been found in archaeological sites from several periods. The eggs were well preserved because the camp site was covered over by sand-dunes for so long "It is interesting, that whilst ostrich eggs are not uncommon in excavations, the bones of the large bird are not found," said Amir Gorzalczany of the Israel Antiquities Authority. "This may indicate that in the ancient world, people avoided tackling the ostrich and were content with collecting their eggs."

The proximity of the eggs to the fire pit discovered indicated that they were intentionally collected and used as food.The eggs were crushed but well preserved because the camp site was covered over by sand for so long and also because of the dry climate of the area. "These camp sites were quickly covered over by the dunes and were re-exposed with the sand movement over hundreds and thousands of years," Lauren Davis said. "This fact explains the exceptional preservation of the eggs, allowing us a glimpse into the lives of the nomads who roamed the desert in ancient times.

3,000-Year-Old Bakery Found in Armenia

In May 2023, Polish scientists digging at the Metsamor archaeological site in Armenia announced they had found a large building they believe was a bakery. As they dug into the brown dirt around the building they uncovered a layer of some dusty, white substance. Initially, archaeologists thought the material was just that: ashes, Science in Poland said in a May 12, 2023 news release, but testing revealed the material was preserved ancient flour. The excavation’s lead archaeologist Krzysztof Jakubiak told Science in Poland. Flour is rarely found at archaeological sites, but several sacks worth of flour were unearthed at the ruins, he said, and his team concluded the ruined structure was a 3,000-year-old large-scale bakery. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, May 13, 2023]

Aspen Pflughoeft wrote in the Miami Herald: The massive structure was used from the end of the 11th century B.C. until the beginning of the 9th century B.C., archaeologists said. Initially, it functioned as a public building. Later, furnaces were added, and the building took on an economic role as a place where people likely used wheat flour to bake bread. Eventually, the structure collapsed due to a fire, the release said.

When archaeologists began excavations of the structure, they identified it as a public building, according to a 2022 news release from the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology at the University of Warsaw. Still, the entire building has not yet been excavated and may hold more secrets for archaeologists to uncover, the release said. Excavations of Metsamor began in 1965 and are ongoing. The joint Polish-Armenian excavations began in 2013.

The structure is in a portion of the Metsamor archaeological site known as the lower city, experts said. The lower city is outside the site’s main fortification network. Metsamor is about 20 miles southwest of Yerevan, the capital of Armenia, and near the border with Turkey. The city was continuously inhabited from the 4th millennium B.C. until the 17th century, the release said.

The site’s ancient inhabitants remain a mysterious group of people. Archaeologists don’t know much about them except that they had no written language. Excavations of the oldest part of Metsamor — a walled settlement with a necropolis or cemetery — uncovered about 100 burials. Many of these tombs were empty, having been looted at some point, but one couple’s untouched tomb contained several gold pendants and about 100 jewelry beads. Metsamor expanded into a larger fortress surrounded by seven temple sanctuaries between the 11th and 9th centuries B.C. — about the same period as when the bakery was used, the release said. The city emerged as an economic, cultural and political center for the region. Eventually, the city was conquered in the 8th century B.C. and became part of the Urartu kingdom, archaeologists said.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Live Science, Wikipedia, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024