Home | Category: Late Dynasties, Persians, Nubians, Ptolemies, Cleopatra, Greeks and Romans

NUBIA AND NUBIANS

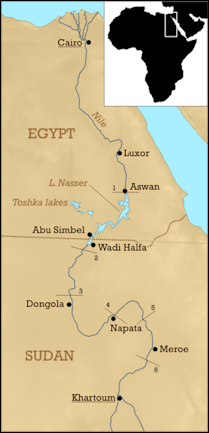

Nubia today Nubia is a loosely defined region of southern Egypt and northern Sudan which used to stretch more or less 800 kilometers from Aswan to the Fourth Cataract on the Nile in Sudan but now extends from south of Luxor to Khartoum, Sudan. In Pharonic times, Nubia was known as the ancient kingdom of Kush. Beginning in the Middle Kingdom the ancient Egyptians obtained gold from Nubia. Gold was called “nub” in ancient Egypt and may be the source of the name Nubia. Ebony, ivory, leopard skins and incenses also came from Nubia or at least were transported through it from sub-Saharan Africa.

Mainly what defines Nubia today are the Nubian people, a black-African people with a history as old as ancient Egypt. The Nubians have their own language, and most of them make a living farming or fishing on the Nile. Others work as captains and crew members on feluccas. In ancient tomb paintings and reliefs they were often depicted as traders and merchants. Generally, Nubians found in Sudan, especially those who live in the desert, are darker skinned than their Egyptian cousins who have intermarried with Arabs.

Nubia variously thrived and survived during the age of Egyptians, Greeks and Romans. Because it lied on the edge of the known world it was regarded as a kind of legendary kingdom shrouded in mystery. The Bible refers to it as Kush. Herodotus described the Nubians as the "tallest and handsomest" people in the world and estimated that they lived to be 120. Roman chroniclers said Nubia was ruled by a dynasty of queens who traveled in chariots pulled by teams of 20 elephants and who lived in houses with translucent walls made from a single stone. They also wrote that Nubian women had considerably larger breasts than women of other races. [Sources: Robert Draper, National Geographic, February 2008; David Roberts, Smithsonian]

Nubia has been shaped by almost every great civilization. During its existence, the New York Times said, conquerors became the conquered; trading partners were reborn as bitter enemies."Five thousand years ago, Egyptian pharaohs left their mark on Nubia, says historian Georg Gerster, "Some two thousand years later, the Egyptian heritage was Africanized by the Nubians. For centuries the Ptolemaic Greeks, and especially the Romans, helped shape Nubia's destinies, only to give way to a Christian culture that gradually came in. The Middle Ages saw the Arabic influence, modern times the Turkish."♂

Summarizing Nubia’s year history, Karen Rosenberg wrote in the New York Times,”Beginning in about 3000 B.C., Southern Nubia developed into a powerful kingdom known as Kush. Egypt, increasingly nervous about this neighbor, conquered a large swath of it in 1500 B.C. Four centuries later the Egyptian empire collapsed; a dark age followed. Then, around 900 B.C., Nubia rose again. By 750 B.C., its Napatan kings had control of Egypt — at least until the Assyrians arrived, in 650 B.C. [Source: Karen Rosenberg, New York Times, March 24, 2011]

RELATED ARTICLES:

TWENTIETH FIFTH DYNASTY (780 – 656 B.C.): THE KUSHITE (NUBIAN) PERIOD OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT SOURCES ON NUBIA AND ETHIOPIA africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Nubia: African Kingdoms on the Nile” by Marjorie M. Fisher, Peter Lacovara , et al. (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Nubian Pharaohs of Egypt: Their Lives and Afterlives” by Aidan Dodson (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia” by Geoff Emberling and Bruce Williams (2021) Amazon.com;

“Nubia: Lost Civilizations” by Sarah M. Schellinger (2023) Amazon.com;

“New Perspectives on Ancient Nubia” by Aaron Brody, Solange Ashby (2024) Amazon.com;

“Nubian Pharaohs and Meroitic Kings: The Kingdom Of Kush” by Necia Desiree Harkless (2006) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt and Nubia — Fully Explained: A New History of the Nile Valley” by Adam Muksawa 2023) Amazon.com;

“Arts of Ancient Nubia” by Denise Doxey (2018) Amazon.com;

“Jewels of Ancient Nubia” by Yvonne Markowitz, Denise Doxey (2014) Amazon.com;

“Afterglow of Empire: Egypt from the Fall of the New Kingdom to the Saite Renaissance”

by Aidan Dodson (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Late New Kingdom in Egypt (c. 1300–664 BC) A Genealogical and Chronological Investigation (Oxbow Classics in Egyptology) by M. L. Bierbrier (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2017) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of Ancient Egypt” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

Kush

ancient Nubia The Kingdom of Kush, also known as the Kushite Empire, or simply Kush, was an ancient kingdom in Nubia, centered along the Nile Valley in what is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt. The Kushite kingdom controlled a vast amount of territory in Sudan between 800 B.C. and the A.D. fourth century. [Source: Wikipedia]

The city-state of Kerma emerged as the dominant political force between 2450 and 1450 B.C. controlling the Nile Valley between the first and fourth cataracts, an area as large as Egypt. The Egyptians were the first to identify Kerma as "Kush" probably from the indigenous ethnonym "Kasu".

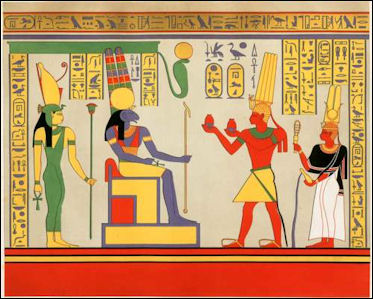

Much of Nubia came under Egyptian rule during the New Kingdom period (1550–1070 B.C.). Following Egypt's disintegration amid the Late Bronze Age collapse, the Kushites reestablished a kingdom in Napata (now modern Karima, Sudan). Though Kush had developed many cultural affinities with Egypt, such as the veneration of Amun, and the royal families of both kingdoms occasionally intermarried, Kushite culture, language and ethnicity was distinct; Egyptian art distinguished the people of Kush by their dress, appearance, and even method of transportation. Pyramid building was popular among the Kushites. They built them long after the Egyptian stopped — until their kingdom collapsed in the A.D. 4th century.

In the 8th century B.C., King Kashta ("the Kushite") peacefully became King of Upper Egypt. His successor Piye invaded Lower Egypt, establishing the Kushite-ruled Twenty-fifth Dynasty. The monarchs of Kush ruled Egypt for over a century until the Assyrian conquest in the mid-seventh century B.C. After this the Kushite imperial capital was located at Meroë, during which time it was known by the Greeks as Aethiopia. From the third century B.C. to the A.D. third century AD, northern Nubia was invaded and annexed by Egypt. Ruled by the Macedonians and Romans for the next 600 years, this territory would be known in the Greco-Roman world as Dodekaschoinos. It was later taken back under control by the fourth Kushite king, Yesebokheamani. The Kingdom of Kush persisted as a major regional power until the A.D. fourth century.

Nubian Civilization

Scholars divide Nubian history into six distinct cultures between 3800 B.C. and A.D. 600. It was a rival of ancient Egypt and lasted considerably longer than ancient Greece or the Roman Empire. Nubia was known as Ta-Seti ("Land of the Bow"), Yam or Wawat to the Egyptians, and Aethiopia to the Greeks and Romans (Ethiopia was called Abyssinia).

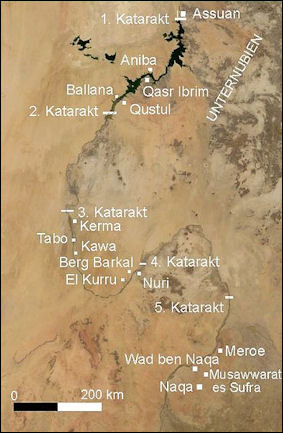

Nubian civilization was located along a 1,000-mile stretch of the Nile in the middle of the one of driest and hottest parts of the world. In much of Nubia rain never falls. There is much less fertile land than in Egypt and the cataracts (canyons with big rapids) on the Nile make navigation for long stretches impossible. As was true with the “Lower” and “Upper” designations of ancient Egypt “Lower” referred to the northern kingdom of Nubia and “Upper” refers to southern kingdom with the Nile being the point of reference. “Lower Nubia” lies on the northern, down-river part of the Nile roughly between Aswan and the Third Cataract of the Nile and “Upper Nubia” lies on the southern upper river part of the Nile roughly between Third Cataract of the Nile and present-day Khartoum.

Nubia was centered around the city-states of Napata, El Kurru and Jebel Barkal, near the Fourth Cataract of the Nile. Other important cities included Aswan at the First Cataract, Karanog and Quustul north of the Second Cataract, Kerma at the Third Cataract, and Meroe and Naga near the Sixth Cataract. (Khartoum is located further south where the White Nile and Blue Nile join to form the Nile.

Ancient Nubia Timeline

The Nubian civilization grew in power just as Egypt’s Middle Kingdom was in decline around 1785 B.C. By 1500 B.C., the Nubian empire roughly stretched from Wadi Halfa south to Meroë. Centered on its original capital at Napata, the Nubian ruling dynasty continued to flourish militarily and economically through the ninth century B.C. [Source Núria Castellano, National Geographic History]

Nubia pyramids 8th Century B.C. Construction of the south and west cemeteries begins in Meroë, then the second city of the Kingdom of Kush, whose capital was at Napata. Núria

730 B.C.: the Nubian king, Piye, successfully invaded and conquered Egypt, extending his control to the whole Nile Valley. Piye became the first pharaoh of Egypt’s 25th dynasty (ca 770-656 B.C.), the so-called Black Pharaohs.

3rd Century B.C.: As space in Meroë’s south cemetery runs out, expansion begins in the north cemetery of the city’s growing necropolis.

250 B.C.: King Arakamani relocates the royal necropolis from near Napata to Meroë, which becomes the kingdom’s spiritual and political capital.

1st Century A.D.: Queen Amanirenas leads her troops against the Romans. Her successor, Amanishakheto, is buried with costly grave goods.

2nd Century A.D.: Building methods change. The Meroë pyramids are faced with brick instead of stone, and then a layer of plaster, which is painted.

A.D. 350: An invasion by the kingdom of Axum brings Meroë's dominance to an end. The city and royal necropolis are eventually abandoned.

Neglect and Prejudice in the Study of Nubian History

One of the reasons why Nubia was given a short shrift in ancient history is partly out prejudice towards its largely black population. A Nubian queen once wrote Alexander the Great, "Do not despise us for the color of our skin. In our souls were are brighter than the whitest of people."

Most of what has been written about the Nubians originated from its enemies: the Egyptians first and foremost but also from Hebrews, Greeks, Romans and Persians. When Nubian achievements were recognized the credit was often is given ot the Egyptians not the Nubians. Even famed early-20th-century Harvard Egyptologist George Resiner — who offered the first archeological evidence that Nubians ruled over ancient Egypt — qualified his own observations by insisting that black Africans could not possibly have constructed monuments as grand as the ones he found in Nubia. He believed Nubian leaders were light-skinned Egypto-Libyans who ruled over primitive Africans.

Taharqa queen The first archaeologists to make significant Nubian finds did so below the Fourth Cataract at the royal cemeteries of El Kurru. The concluded that what they found could not have come from black Nubians but must have by white-skinned Libyans. For decades everything found in Nubian was either categorized as "decadent" and "peripheral" or as derived from Egypt.

Karen Rosenberg wrote in the New York Times, “How little we know about this ancient culture. For one thing, Nubians did not develop their own written language until the second century B.C.; their story has largely been told by the Egyptians, who were prolific scribes. We know, for instance, that an Egyptian official named Harkhuf was sent to Nubia to obtain incense, ebony, oils, panther skins, ivory and a pygmy...When Nubians appear in Egyptian murals and statues, it’s often as primitives or prisoners. More recently, our own Western prejudices — namely the idea that geographic Egypt was not a part of “black” Africa — have contributed to the dearth of knowledge about Nubia....Reisner, for instance, identified large burial mounds at the site of Kerma as the remains of high Egyptian officials instead of those of Nubian kings. [Source: Karen Rosenberg, New York Times, March 24, 2011]

Archaeologist Geoff Emberling, the organizer of an exhibition of Nubian art wrote: “We now recognize that populations of Nubia and Egypt form a continuum rather than clearly distinct groupsand that it is impossible to draw a line between Egypt and Nubia that would indicate where “black” begins.”

While ancient Egypt has been the focus of much and attention and research, ancient Nubia has largely been ignored. Only in the last 40 years or so has it been the subject of any kind of study at all. Nubian archaeology was greatly set back by the construction of the Aswan dam in the 1960s. The presence of an Islamic government and civil war and the submergence of sites by Lake Nasser has made it difficult for archaeologists to work in Sudan. In recent years serious archeological research has been disrupted by the construction of a dam in Sudan, 1000 kilometers upstream from the Aswan High Dam. The huge Merowe Dan was completed in 2009.

Afro-Americans have embraced the Nubians as a kind of chosen people for them. A rap group on New York calls itself Brand Nubian and a Nubian hero "Heru: Son of Ausur" is featured in a new comic book.

Early Nubian History

The first Nubian culture, unglamourously dubbed the A-Group by Harvard archaeologist George Reiner in the 1920s, emerged around 3800 B.C. Little is known about it other than it was a rival of pre-Dynastic Egypt and it produced lovely "eggshell" pottery (named after its thins walls) with red and white geometric patterns that resemble weaving. Around 2800 B.C., reference to the A-Group appear in Egyptian hieroglyphics.Aggression by Egypt in the third millennium forced the A-Group into a remote area above the Second Cataract. Around 2300 B.C. a pair of new cultures sprang up. One of them, centered in lower Nubia and known as the C-Group, produced elaborate tombs, raised cattle, worshiped gods in a cattle cult and flourished during a 400-year-long period of peace with the Egyptians.

Matt Stirn wrote in Archaeology magazine: A Swiss team, now under the direction of University of Neuchatel archaeologist Matthieu Honegger found that beginning around 3100 B.C., driven in part by an increasingly arid climate, people began to settle on the island in the Nile where Kerma would rise. These new arrivals lived in small settlements and used red brushed ceramics of a type that their descendants at Kerma would also use, and placed their huts in a distinctive semicircular pattern. [Source: Matt Stirn, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2020]

“In addition to evidence of ambitious building projects and a growing economy, finds dating to early in the city’s history indicate the arrival of the C-Group identified by Reisner, possibly from Darfur in western Sudan or modern-day South Sudan. Their emergence in Nubia, marked by the sudden appearance of incised black-and-white ceramics and distinctive grave decorations, suggests that they immigrated quickly into the region. Shortly after their arrival, these new people rapidly integrated with the local Nubians and began to assimilate into the city’s culture, while maintaining a number of their own traditions.

Although evidence shows that the C-Group suddenly disappeared from Kerma around 2300 B.C. and moved north toward Egypt, their brief presence helped establish a multicultural foundation that would endure throughout Kerma’s history. Kerma continued to thrive after the departure of the C-Group people. Around 1900 B.C. Egyptian armies built a colossal series of fortresses around the Second Cataract and used them to thrust deep into Nubia, perhaps as part of an effort to get a hold of Nubia's gold mines that were being opened at that time in the Eastern Desert.

Around 1700 B.C., Egypt was racked by internal problems and withdrew from the fortresses. By 1500 B.C. the Nubian empire stretched between the Second and Fifth Cataracts. Hints of greatness from this period have been found. Nubian Queen Kawait, for example, is hewn on her sarcophagus with her hair dressed by a noble woman believed to have been sent from Nubia to make a diplomatic marriage with the 11th-dynasty Egyptian pharaoh Mentuhotpe. After the Egyptians left, a grand kingdom emerged at Kerma with palaces, cemeteries and magnificent royal tombs. One king was buried in a football-field-size tumuluses with 400 concubines and a chamber occupied by gold-covered bust and gold, bronze and ivory treasures).

Gebel Moya — A Very Old Agricultural Site in Southern Sudan

Isabelle Vella Gregory wrote: Gebel Moya is a large agricultural-pastoral site located below the Nile’s Sixth Cataract in Sudan. It lies between the Blue Nile and White Nile. It was first excavated by Henry Wellcome in the early twentieth century and was known as a cemetery until 2017, when fieldwork was renewed by a joint international mission. Current excavations show that, in addition to being a major cemetery, the site bears traces of Mesolithic habitation. Over a period of 5,000 years the area witnessed rapid climate change.[Source Isabelle Vella Gregory, University of Cambridge, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2024 escholarship.org ]

Gebel Moya lies around 240 kilometers south of Khartoum. The name Gebel Moya means, in Arabic, “Mountain of Water” and refers to the nearby village and mountain valley in an area that is now arid. Archaeological remains are present in the valley above the village. Officially, these are known as Site 100, although the locals simply refer to the area as Gebel Moya. The nearest large town is Sennar.

The ongoing work of the current mission, directed by Ahmed Adam, Michael Brass and Isabelle Vella Gregory has confirmed the site to be a major agro-pastoral cemetery stretching over 5,000 years, and with firm traces of Mesolithic habitation. Thus far, the site has yielded evidence of rapid historic climate change and the second oldest domesticated sorghum in the world. Ongoing work is focused on reconstructing the ancient flora and fauna. It is now clear that Site 100, long considered insignificant by scholars, was home to dynamic communities across the millennia.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Gebel Moya (Site 100) by Isabelle Vella Gregory UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology escholarship.org

Kerma

The ancient Nubian city of Kerma sat at the northern end of the Great Bend of the Nile, where the great river forms a magnificent 400-kilometer (250-mile) curve, reminiscent of a giant S, marking the southern boundary of Nubia. Kerma emerged around 1785 B.C. at a major city as Egypt’s Middle Kingdom was declining. Archeologists working there have unearthed large stone statues of Nubian pharaohs and found dense urban centers and evidence of trade in gold, ebony and ivory.

Matt Stirn, wrote in Archaeology magazine: At the center of the modern town rises a five-story mudbrick tower, or deffufa in the Nubian language, which has kept watch there for more than 4,000 years. Consisting of multiple levels, an interior staircase leading to a rooftop platform, and a series of subterranean chambers, the Deffufa once functioned as a temple and the religious center of a Nubian city that was founded there around 2500 B.C. on what was once an island in the middle of the Nile. Also known as Kerma, it was the earliest urban center in Africa outside Egypt. [Source: Matt Stirn, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2020]

Kerma Below the Deffufa, archaeologist Charles Bonnet of the University of Geneva has spent five decades excavating Kerma and its necropolis. Fortifications that had been unearthed by Bonnet’s team showed that around 2500 B.C., the people of Kerma constructed a large fortress, and that a dense urban landscape quickly grew up around it. The city’s residents built circular huts, larger communal wooden structures, bakeries, and markets. Large ceramic vessels throughout Kerma seem to have provided public drinking water, likely for both citizens and visitors. A small chapel was constructed where the Deffufa would later stand, and the entrance to the city was marked by a mudbrick-and-wood gate built in a style still evident in Nubian houses today. [Source: Matt Stirn, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2020]

Firmly established in a fortified capital, around 1750 B.C., the kings of Kerma ordered an even more massive palace to be built. Their royal tombs also became even more lavish. At the southern end of the necropolis, Bonnet and Honegger have unearthed very large tombs, some measuring 200 feet in diameter and each containing more than 100 human sacrifices.

Royal quarters with an elaborate courtyard were constructed near the city center. Around this time, nobles were first entombed in the necropolis to the east of the site. In several ceramic workshops nearby, artisans created a style of ornate dining ware only found in the nobles’ tombs. Bonnet believes these dishes were used during funeral rituals that involved meals held between mourning families and the recently deceased. The discovery of ceramic Egyptian trade seals, faience artifacts, and ivory and jewelry from southern Sudan, shows that Kerma was growing into an important trade center. Farmers contributed to the economy during this time by raising cattle and planting legumes and grain in irrigated ditches surrounding the city walls. Bonnet’s team uncovered well-preserved evidence of this in traces of wooden plowshares, holes dug in the soil for as-yet-unplanted crops, and the footprints of both people and of oxen teams, along with thousands of domesticated cattle prints pressed into the hardened mud as if they had been made only a few weeks before.

Was Kerma an Egyptian Colony or an African Cultural Center?

Matt Stirn wrote in Archaeology magazine: Much of what scholars know of early Nubian history comes from ancient Egyptian sources, and, for a time, some believed Kerma was simply an Egyptian colonial outpost. The pharaoh Thutmose I (r. ca. 1504–1492 B.C.) did indeed invade Nubia, and his successors ruled there for centuries, just as later Nubian kings invaded and held Egypt during the 25th Dynasty (ca. 712–664 B.C.). The ancient history of Egyptians and Nubians is, thus, closely intertwined.

“Bonnet began working at Kerma in 1976, some 50 years after Egyptologist George Reisner, the first archaeologist to dig at the site, closed his excavations. Most artifacts Reisner excavated were distinct from what he had seen in Egypt, which led him to determine that the inhabitants of the site were from a different culture, which he named Kerma after the surrounding modern town. Reisner also recognized that different African cultures had coexisted in the ancient city. One of these he called the C-Group, a somewhat enigmatic culture that would become key to understanding the site’s origins. Despite recognizing that Kerma was populated by ancient Nubians, Reisner did not believe that the Kerma people had been capable of constructing such a magnificent site, and assumed that they had received help from the Egyptians. The Deffufa, he thought, was most likely the palace of Kerma’s Egyptian governor.

Bonnet disagreed. After excavating sites in the Second Cataract area, he told National Geographic, “It was a kingdom completely free of Egypt and original with its own construction and burial customs. After unearthing tombs, buildings, and pottery that predated the 1500 B.C. Egyptian invasion of Nubia, Bonnet realized that Kerma was not merely an Egyptian colony, but had been built and ruled by Nubians. “The country was wrongly believed to have only depended on Egypt,” says Bonnet. “I wanted to reconstruct a more accurate history of Sudan.” In addition to determining that Nubians had founded the city, the team began to identify evidence of other African cultures at Kerma. They discovered round huts, oval temples, and intricate curved-wall bastions that were distinct from both Egyptian and Nubian architecture, and instead mirrored buildings archaeologists have unearthed in southern Sudan and regions in central Africa. “We realized that the tombs, palaces, and temples stood out from Egyptian remains, and that a different tradition characterized the discoveries,” says Bonnet. “We were in another world.”

Bonnet’s excavations have offered a markedly Nubian perspective on the earliest days of Kerma and its role as the capital of a far-reaching kingdom that dominated the Nile south of Egypt. His finds there and at a neighboring ancient settlement known as Dukki Gel suggest that this urban center was an ethnic melting pot, with origins tied to a complex web of cultures native to both the Sahara, and, farther south, parts of central Africa. These discoveries have gradually revealed the complex nature of a powerful African kingdom.

“Some buildings Bonnet has unearthed at Kerma suggest that African influences from outside Nubia endured, and that foreign people continued to live at Kerma even after the C-Group departed. To him, the building styles there represent a conglomeration of cultures, with architecture not only influenced by Egyptian practices, but also inspired by other African traditions. In particular, a courtyard in the southern part of the city surrounded by circular structures and a small fort featuring curved defensive walls allude to African traditions that resemble modern architecture in Darfur, Ethiopia, and South Sudan. Much like the C-Group, however, the precise identity of these later African populations at Kerma remains unknown. Little archaeological research has been conducted in southern Sudan, and there are very few known sites with which to compare Kerma.

Nubians and Egyptians

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: In its 3,000-year history as a state, ancient Egypt had a complicated, constantly changing set of relations with neighboring powers. With the Libyans to the west and the Babylonians, Hittites, Assyrians, and Persians to the northeast, Egypt by turns waged war, forged treaties, and engaged in mutually beneficial trade. But Egypt’s most important and enduring relationship was, arguably, with its neighbor to the south, Nubia. The two cultures were connected by the Nile River, whose annual flooding made civilization possible in an otherwise harsh desert environment. Through their shared history, Egyptians and Nubians also came to worship the same chief god, Amun, who was closely allied with kingship and played an important role as the two civilizations vied for supremacy. During its Middle and New Kingdoms, which spanned the second millennium B.C., Egypt pushed its way into Nubia, ultimately conquering and making it a colonial province. The Egyptians were drawn by the land’s rich store of natural resources, including ebony, ivory, animal skins, and, most importantly, gold. [Source:Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2015]

Nubia was a major source of gold, labor and exotic materials for ancient Egypt. The Egyptians were using gold as early as 2000 B.C. The Egyptian often referred to the Nubians as "vile," "miserable" and "wretched." Pharaohs made images of Nubians on their foot stool so they could crush them with their sandals. Fortresses were built to hold off the Nubians. The Egyptians built garrisons along the Nile and installed Nubia chiefs as administrator. The children of favored Nubians were educated in Thebes.

Nubians embraced Egyptian culture and arguably the first to be consumed by Egyptomania. They became highly assimilated and venerated Egyptian gods, particularly Amun, used the Egyptians language, adopted Egyptians burial styles and later even built pyramids. Timothy Kednall if Northeastern University told National Geographic, the Nubians “had become more catholic than the pope.” Today Sudan has more pyramids than Egypt.

Matt Stirn wrote in Archaeology magazine: An abundance of Egyptian artifacts and the discovery of ceramic trade seals bearing the names of Egyptian pharaohs in Kerma’s necropolis suggest that, despite their military clashes, the two powers maintained close economic connections during this time. According to contemporaneous Egyptian inscriptions, however, this relationship deteriorated for good after a failed invasion of Egypt by Kerma in 1550 B.C. [Source: Matt Stirn, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2020]

Despite this, Nubia never really became an integral part of the Egyptian kingdom, it was usually governed by viceroys, who bore the titles of the “royal son of Ethiopia," and “the superintendent of the southern countries “(or “of the gold countries "). Toby Wilkinson wrote in “The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt”, Whereas Egypt’s relationship with the Near East was, from the start, contradictory and complex, its attitude toward Nubia was far more straightforward . . . and domineering. Before the beginning of the First Dynasty, when the predynastic kingdoms of Tjeni, Nubt, and Nekhen were rising to prominence in Egypt, a similar process was under way in lower (northern) Nubia, centered on the sites of Seyala and Qustul. With a sophisticated culture, kingly burials, and trade with neighboring lands, including Egypt, lower Nubia displayed all the hallmarks of an incipient civilization. Yet it was not to be. The written and archaeological evidence tell the same story, one of Egyptian conquest and subjugation. Egypt’s early rulers, in their determination to acquire control of trade routes and to eliminate all opposition, moved swiftly to snuff out their Nubian rivals before they could pose a real threat. The inscription at Gebel Sheikh Suleiman, discussed in the previous chapter, which shows a giant scorpion holding in its pincers a defeated Nubian chieftain, is a graphic illustration of Egyptian policy toward Nubia. [Excerpt “The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson, Random House, 2011, from the New York Times, March 28, 2011]

Nubian Gold Mines

The Ancient Egyptians got a great deal of their gold from Nubia. We do not know for certain where the Nubian gold mines were located, or to which the route of Redesieh was to lead; the inscription does not allude to the mines of Eshuranib, for, apart from other reasons, the king was endeavoring at the same time to open a way to this latter district also. We learn this from an inscription of Ramses II.

Texts are still extant describing the working of the Nubian goldmines. They picture to us the difficulties of mining in the desert so far from the Nile valley — each journey became a dangerous expedition, owing to want of water and to the robber nomads. When King Senusret I. had subjected Nubia, Ameny, our oft-mentioned nomarch, relates that he began immediately to plunder the gold district. “I went up," he says, “in order to fetch gold for his Majesty, King Senusret I. (may he live always and for ever). I went together with the hereditary prince, the prince, the great legitimate son of the king, Ameny (life, health, and happiness!) and I went with a company of 400 men of the choicest of my soldiers, who by good fortune arrived safely without loss of any of their number. I brought the gold I was commissioned to bring, and was in consequence placed in the royal house, and the king's son thanked me. " The strong escort, which in this case was required mainly for the protection of the gold, shows the insecurity of the road. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

See Separate Article: PRECIOUS METALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: GOLD, SILVER, MINING, SOURCES africame.factsanddetails.com

Egyptian Invasions of Nubia

Nubia was periodically occupied by Egypt beginning in the 3rd millennium. The pharaoh Sneferu recorded a great victory against the Nubians in 2600 B.C. and he bragged 7,000 Nubians and 200,000 domestic animals were captured. In 1550 B.C., Nubia was invaded again by Egypt. The conflicted last about 100 years and when it was over Egypt claimed much of Nubia and controlled it for 350 years, during which time Nubia became throughly Egyptianized as is reflected by Nubian art of that time.

The Old Kingdom Pharaoh Pepi I (2305–2118 B.C. ) and New Kingdom Pharaoh Tuthmosis III ( 1479–1425 B.C.) conquered the Nubians. Rames II (1279–1213 B.C.) lead campaigns in Nubia The Egyptian Pharaohs could be quite cruel. Thutmose I once sailed into Thebes with the naked body of a rebellious Nubian chieftain dangling from the prow of his ship. Many Nubians captured in the fighting were conscripted into the Egyptian army.

Toby Wilkinson wrote in “The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt”, The inscription at Gebel Sheikh Suleiman...which shows a giant scorpion holding in its pincers a defeated Nubian chieftain, is a graphic illustration of Egyptian policy toward Nubia. A second inscription nearby, dating to the threshold of the First Dynasty, completes the story. It shows a scene of devastation, with Nubians lying dead and dying, watched over by the cipher (hieroglyphic marker) of the Egyptian king. The prosperous city- states of the Near East, which were useful trading partners and geographically separate from Egypt, could be allowed to exist, but a rival kingdom immediately upstream was unthinkable. Following Egypt’s decisive early intervention in lower Nubia, this stretch of the Nile Valley — though it would remain a thorn in Egypt’s side — would not rise again as a serious power for nearly a thousand years. [Excerpt “The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson, Random House, 2011, from the New York Times, March 28, 2011]

Impacts of Egyptian Invasions of Nubia

Matt Stirn wrote in Archaeology magazine: Following the failed invasion of Egypt by Kerma in 1550 B.C., the Egyptians responded with a series of invasions under Thutmose I around 1500 B.C., and Thutmose II (r. ca. 1492–1479 B.C.) some 20 years later. These resulted in brief Egyptian occupations of Nubia that were subsequently rebuffed by revolts and counterattacks. In 1450 B.C., Thutmose III (r. ca. 1479–1425 B.C.) launched a final campaign into Nubia. He successfully conquered Kerma and established a firm rule over the region. Scholars had long assumed that after the Egyptians conquered Kerma they moved the capital half a mile north to the site of Dukki Gel, where Bonnet and his team have excavated in recent years. The obvious presence of Egyptian buildings at Dukki Gel from the time of Thutmose I and later had always suggested that the city was founded by Egyptians, and that it functioned as a colonial center in much the same way Reisner once assumed Kerma had. [Source: Matt Stirn, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2020]

“But when Bonnet and his team began digging at the site, they unearthed fresh evidence of African architecture postdating the Egyptian invasion, a find that suggests African traditions continued at Dukki Gel perhaps after Kerma was abandoned. Even more surprising, once the team dug below the Egyptian settlement at Dukki Gel, they uncovered circular African buildings dating to before the Egyptian conquest. These buildings were defended by walls that have no known prototypes in the Nile Valley. Even though ancient cities were rarely built as close together as Kerma and Dukki Gel, for Bonnet the conclusion was inescapable — this was an urban center that dated to the same time that Kerma was at its height.

Karen Rosenberg wrote in the New York Times, “Egypt’s assimilation of Nubia into its empire prompted some political niceties. The name “Kush” remained, but the adjective “vile” was dropped; the Egyptian governor of Nubia was called the “King’s Son of Kush.” The Egyptian cult of Amun was modified to suggest Nubia’s “holy mountain,” Gebel Barkal, as that deity’s birthplace. For its part, Nubia adopted some Egyptian dress styles and burial customs, even after conquering Egypt. One was the use of the pyramid; earlier Nubian rulers had been entombed in giant mounds. Another was the addition of shawabtis, small figures thought to work on behalf of the deceased in the underworld. [Source: Karen Rosenberg, New York Times, March 24, 2011]

Archaeology magazine reported: Two shrines at Gebel el-Silsila on the banks of the Nile River in southern Egypt — thought to have been completely destroyed by an earthquake and erosion — have been discovered largely intact. The shrines, located by a team from Lund University in Sweden led by Maria Nilsson, served as memorials to elite families. One includes statues of a man, his wife, and a son and daughter. Hieroglyphics identify the man as Neferkhewe, the “overseer of foreign lands” under pharaoh Thutmose III (r. 1479–1425 B.C.), and his wife as Ruiuresti. “The mother’s name is foreign and the part that we have of the daughter’s name is also foreign,” says John Ward, the project’s associate director. “So it looks as if we have a Nubian family who have taken on the Egyptian religion and produced this shrine in order to gain immortality.” [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

Around 1080 B.C. internal problems racked Egypt again and Nubia won it autonomy. Little is known about what happened in Nubia until around 850 B.C. Nubia conquered Egypt in 730 B.C. and ruled it for 60 years (from 750-661 B.C.), and survived as an Egyptianized kingdom (Kush: capital Meroe) for 100 years.

25th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt: Nubian Rule of Egypt

During the 25th Dynasty, native princes of Kush (Nubia-modern Sudan) conquered a weak Egypt and established themselves leaders of the region. They restored ancient customs, had old texts recopied, built new temples in Thebes and revived pyramid burials. Much of the art and sculpture produced during this time was an imitation the Old and Middle Kingdom styles, some of it so well executed that even experts can’t tell the difference. The 25th dynasty ended in turmoil when an Assyrian invasion of Egypt caused it to fall from power. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

The 25th Dynasty Nubian kings were: Alara B.C. Kashta B.C. Piye 747-716 B.C. Shabako 716-702 B.C. Shabatka 702-690 B.C. Taharqa 690-664 B.C. Tantarnani 644-656 B.C.

On the 25th Dynasty, Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “ For much of Egyptian history, Nubia had been regarded merely as a source of manpower and minerals for the Egyptian state. Then, around 730 B.C., tables were turned, and the Nubian King Piye invaded and conquered Egypt. The king and his successors were, however, steeped in Egyptian culture, and viewed themselves as the renewers of ancient glories, rather than as foreign incomers. As such, they revived the ancient custom of pyramid building, which had been dropped by the pharaohs some eight centuries before-shown above are the ruins of the pyramid of Taharqa (690-664 B.C.). Despite this history, Taharqa's successor was soon driven out of Egypt by an Assyrian invasion, never to return. [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, Egyptologist, University of Bristol, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

RELATED ARTICLES:

TWENTIETH FIFTH DYNASTY (780 – 656 B.C.): THE KUSHITE (NUBIAN) PERIOD OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Meroe

After Egypt’s New Kingdom collapsed around 1069 B.C., the kingdom of Kush rose in Nubia, with its court based in Napata. After the 25th dynasty Nubian pharaohs lost power, they retreated south from Egypt to Kush. First the Assyrians drove them from Egypt to Napata, only to be forced farther south at the beginning of the sixth century B.C., when Pharaoh Psamtek II, part of the 26th dynasty, sacked Napata.

Núria Castellano wrote in National Geographic History: The Kushites designated the city of Meroë, which sat farther south along the Nile, as the new capital. This new location was carefully considered. Not only strategically positioned at the crossroads of inland African trade routes and caravan trails from the Red Sea, the land around Meroë was also fertile and blessed with significant natural resources—iron and gold mines that fostered the development of a metals industry, especially goldworking. [Source Núria Castellano, National Geographic History]

Gradually the center of the Nubian kingdom shifted further south to below the Fourth Cataract. Meroe and Kush flourished until A.D. 350 in splendid isolation as the rest of Egypt suffered through repeated invasions from Assyrians, Persians, and Greeks. Because of Meroë’s distance, the Kushites were able to retain their independence, developing their own vibrant hybrid of Egyptian culture and religion. The Nubians there produced distinctive art and built cities around artificial reservoirs. Efforts by the Persians and Romans to conquer them were unsuccessful. [Source Núria Castellano, National Geographic History]

Through their isolation, the Meriotes lost the use of Egyptian hieroglyphics and developed a quasi-cursive script alphabet now called Meroitic. Thus far 23 letters have been figured out using small fragments of Rossetta-stone-like tablets but the language remains largely undeciphered. It s unrelated languages used by modern Nubians and is unlike an other known languages.

See Separate Article: NUBIA AFTER THE ANCIENT EGYPTIAN 25TH DYNASTY: MEROE AND THE NAPATA PERIOD africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Nubians at Philae

Philae lies just south of the Nile’s first cataract — one of six rapids along the river — which marked the historical border between ancient Egypt and Nubia, also known as Kush. Isma’il Kushkush wrote in Archaeology Magazine: In this region of Kush, called Lower Nubia, the temple complex at Philae was just one of many that were built on islands in the Nile and along its banks. Throughout the long history of Egypt and Nubia, Lower Nubia was a kind of buffer zone between these two lands and a place where the two cultures heavily influenced one another. “Often official Egyptian texts were demeaning to Nubians,” says Egyptologist Solange Ashby of the University of California, Los Angeles. “But this cultural arrogance doesn’t reflect the lived reality of Egyptians and Nubians being neighbors, intermarrying, sharing cultural and religious practices. These were people who interacted for millennia.” [Source: Isma’il Kushkush, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2021]

The earliest clear evidence of the Nubian connection to Philae dates to the reign of the Kushite kings who invaded Egypt in the eighth century B.C. and ruled it for nearly a century as the 25th Dynasty. One of the dynasty’s mightiest pharaohs, Taharqa (r. 690–664 B.C.), oversaw the construction of new temples and a revival of ancient Egyptian culture in the Nile Valley. This included commissioning a complex at Philae dedicated to Amun, a chief ancient Egyptian and Kushite deity closely associated with kingship. Blocks from this temple inscribed with Taharqa’s name were unearthed in the twentieth century before the island was submerged.

From 300 B.C. to A.D. 300, Nubia was ruled from the capital city of Meroe. The Meroitic kings took a special interest in Philae, where the most important Egyptian temple dedicated to Isis was located. In part this may have been because the island had been significant to the Nubians for centuries. Even its ancient Egyptian name, Pilak, which means “Island of Time” or “Island of Extremity,” may have been of Nubian origin. And while many of the other temples on Philae were built by Egypt’s Ptolemaic kings, Greek rulers who held sway from 304 to 30 B.C., the continued survival of the religious practices there owed much to the Meroitic kings. They, and later other Nubian rulers, funded annual celebrations at Philae and devoted resources to maintaining its temples in the centuries before Christianity finally eclipsed Egypt’s ancient traditions. [Source: Isma’il Kushkush, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2021]

Recent research has highlighted the deep and enduring nature of this connection. Ashby has studied a corpus of ancient inscriptions recorded at Philae in the early twentieth century by British Egyptologist Francis Llewellyn Griffith and, more recently, by the late Egyptologist Eugene Cruz-Uribe of Indiana University East. Among these, she identified at least 98 inscriptions that were written on the walls of the temples at Philae on behalf of Nubians. These are mainly in the form of prayers offered to the gods. These inscriptions were written mostly in Greek and Demotic, a script used for writing ancient Egyptian, though some were also written in the Nubians’ own Meroitic script, which remains largely undeciphered. Ashby expected the inscriptions to have been commissioned by Nubian pilgrims to Philae, but she found that many were left by Nubians who had a much deeper connection to the island. “High-ranking priests, temple financial administrators, and officials were sent to Philae as representatives of the king in Meroe,” says Ashby. “Those Nubians eventually held power in the temple administration.”

Nubia Archaeology and Looting

Núria Castellano wrote in National Geographic History: A.D. Over the centuries, rumors spread of monuments found Sudan and the gold they contained, eventually reaching the Italian tomb robber Giuseppe Ferlini. In 1834 Ferlini arrived in Meroë, where he set about looting the graves. The damage Ferlini caused is still lamented by archaeologists, but the few exquisite artifacts he brought back opened the eyes of European scholars to this mysterious culture that had absorbed the ancient traditions of pharaonic Egypt. [Source Núria Castellano, National Geographic History]

The jewels of Meroë’s first-century B.C. queen Amanishakheto were stolen in 1834 by Guiseppe Ferlini. Today they are on display in the State Museum of Egyptian Art, Munich, and the Egyptian Museum of Berlin.This gold ring is adorned with the head of the god Amun in the form of a ram.

In the late 20th century, Swiss archaeologist Charles Bonnet spent decades excavating the lands surrounding the southern Nile. He found evidence of a Nubian civilization that had grown rich from trade and contained fertile fields and abundant livestock. The kingdom he researched has similarities with ancient Egypt but was distinct and had its own material culture and traditions.

Samir S. Patel wrote in Archaeology magazine: An archaeological project focused on the city of Dangeil, dating to the Kingdom of Kush, from the 3rd century B.C. to the 4th century a.d., has revealed the results of the excavation of a cemetery. So far, 52 tombs have been excavated with a great variety of grave goods, including large beer jars, a unique set of seven attached bowls, a silver signet ring, and a faience box crafted with udjat eyes, an Egyptian symbol of power and protection. Egyptian, Greco-Roman, and African cultures all influenced Kushite society in the period. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2014]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024