Home | Category: Economics / Art and Architecture

GOLD IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Egyptian alchemists thought that gold was a seed and the silver and copper were food that caused more gold to grow. One ancient Egyptian recipe for "diplosis" of gold called for two parts gold, one part copper and one part silver to be heated and mixed together. The result is twice as much gold (12 carat gold, when mixed the reddish tint of copper and the greenish tint of the silver doesn't change the color of the gold).

Gold was valued by Egyptian pharaohs The Egyptians obtained gold from the Eastern Desert from an early period and from Nubia in the Middle Kingdom. Gold was called “ nub” in ancient Egypt and may be the source of the name Nubia.

Ancient gold miners crushed ore into powder in mortars and crushers made of gray stone. The powdered ore and water was added to pans from which gold was panned out.

Pharaoh Gold Mines, an Egyptian-Australian joint venture, has invested millions of dollars prospecting for gold near Sukkari (500 miles southeast of Cairo) in a southeastern desert of Red Sea using treasure map — a copy of an ancient cutaway papyrus drawing of mine tunnels now residing in an Italian museum — that date back to the reign of Seti I, who ruled from 1290 to 1279 B.C.

The mines were mined by Romans, Britons and Russians. The results from Pharaoh Gold Mines' test drillings have been good. The company is waiting for gold prices to rise and hopes to make a large profit with an open mine.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MINING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

METALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: BRONZE, COPPER, METEORIC IRON africame.factsanddetails.com ;

GEM STONES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Gold and Gold Mining in Ancient Egypt and Nubia: Geoarchaeology of the Ancient Gold Mining Sites in the Egyptian and Sudanese Eastern Deserts” by Rosemarie Klemm and Dietrich Klemm (2012) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Metallurgy” by H. Garland and C. O. Bannister (2015) Amazon.com;

“Nubian Gold: Ancient Jewelry from Sudan and Egypt” by Peter Lacovara and Yvonne J. Markowitz (2019) Amazon.com

“Gold, Frankincense, Myrrh, And Spiritual Gifts Of The Magi” by Winston James Head Amazon.com ;

“Ancient Egyptian Technology and Innovation” by Ian Shaw (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Proceedings of the First Intl. Conf. On Ancient Egypt Mining and Metallurgy”

by Supreme Council of Antiquities (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Bronze Age: A History from Beginning to End” by Hourly History (2024) Amazon.com;

Silver in Ancient Egypt

The Egyptians refereed to silver as "white gold." In ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome silver was used to fight infections. In the 7th century B.C., the world's first coins were minted with a silver and gold alloy called electrum. Traces of platinum have been found in inlays from ancient Egypt, where the metal was probably mistaken for silver.

The Egyptians regarded silver as the most valuable of all precious metals; it stands before gold in all the old inscriptions, and in fact, in the tombs silver objects are much rarer than gold ones. This curious circumstance admits of a very simple explanation: no silver was to be found in Egypt. The “white," as silver was called, was probably imported from Cilicia; the Phoenicians and Syrians carried on this trade in the time of the 18th dynasty. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Either the brisker trade in this metal, or the discovery of new mines, led to a fall in the value of silver during the New Kingdom, for later texts usually mention gold first in the same way that we do. In addition to gold and silver another precious metal, the electron, the mixture of gold and silver. Though this amalgam was in no way beautiful, it was much used for personal adornment and for ornamental vases. The proportion of the gold to the silver was apparently that of two to three.

See Separate Article: MONEY, BARTER AND RATIONING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Goldsmiths in Ancient Egypt

Nubian gold Goldsmiths were held in very high esteem, owing to the fact that they had to provide the temples with figures of the gods. Under the 12th dynasty a "superintendent of the goldsmiths," whose father held like office, was “rewarded by the king (even) in his childhood," and in later life was “placed before others in his office. " Another “superintendent of the goldsmiths of the king," During the New Kingdom, is also called the “superintendent of the artists in Upper and Lower Egypt "; he relates that he knows “the secrets of the houses of gold," by which we may perhaps understand the preparation of the figures of the gods that were guarded with such secrecy. " In addition there were the “goldsmiths," the “chief goldsmiths," and the “superintendents of the goldsmiths "; '' as a rule fathers and brothers carried on the same craft; the goldsmiths' art therefore, like that of the painters and sculptors, was transmitted traditionally from father to son.

The great skill of the Egyptian goldsmiths is proved in the most conclusive manner by the wonderful jewels found on the body of Queen Ahhotep, one of the ancestresses of the New Kingdom; these jewels are now amongst the treasures at Giza. '' The fineness of the gold work, and the splendid coloring of the enamels, are as admirable as the tasteful forms and the certainty of the technique. Amongst them there is a dagger, on the dark bronze blade of which are symbolical representations of war, a lion rushing along, and some locusts, all inlaid in gold; in the wooden handle are inserted three-cornered pieces of precious metal; three female heads in gold form the top of the handle, whilst a bull's head of the same precious metal conceals the place where handle and blade unite. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The sheath is of gold. One beautiful axe has a gilded bronze blade, the central space being covered with the deepest blue enamel, on which King Ahmose is represented stabbing an enemy; above him a griffin, the emblem of swiftness, hastens past. The handle of the axe is of cedar wood plated with gold, and upon it the names of the king are inlaid in colored precious stones. Gold wire is used instead of the straps which in ordinary axes bind the handle and blade together. Perhaps the most beautiful of all these precious things however is the golden breastplate in the form of a little Egyptian temple; King Ahmose is standing in it, Amun and Ra pour water over him and bless him. The contours of the figures are formed with fine strips of gold, and the spaces between them are filled in with paste and colored stones. This technique, now called cloisonne, the same which has been carried to such perfection by the Chinese, was often employed by the Egyptians with great taste. The illustration heading this chapter gives a good idea of the character of the work, but it is impossible to represent the brilliance of the enamel, and the beauty of the threads of gold that divide the partitions.

Every one however was not able, like the fortunate Queen Ahhotep, to employ gold for each and every thing; the art of gilding therefore was early developed. The Berlin Museum possesses a specimen of gilding belonging to the early period between the Old and the New Kingdom, in this specimen the fineness of the reddish gold leaf is remarkable; in later times gilding was much used, but I believe that this industry is represented in a tomb picture as early as the time of the Middle Kingdom.

In 2017, Egyptian archaeologists announced they had discovered a tomb of a prominent goldsmith who lived more than 3,000 years ago, unearthing statues, mummies and jewelry near the Nile city of Luxor. Egypt’s Minister of Antiquities Khaled Al-Anani said on Saturday the tomb dated back to Egypt’s 18th dynasty New Kingdom era — around 15th century B.C. The site includes a courtyard and niche where a statue of the goldsmith Amenemhat and his wife and one of his sons, as well as two burial shafts, the ministry said in a statement. [Source: Reuters, September 9, 2017]

Egyptian Red Gold

Ankh mirror from Tutankhamun'sTomb Tony Frantz and Deborah Schorsch of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote in: “Egyptologists have long noted that the surfaces of many ancient Egyptian objects made of gold bear a distinctive coloration that ranges from a pale reddish hue to a dark purple. This effect is observed on solid cast figures as well as on hammered sheet metal and gold leaf, such that its origin would seem to be independent of the technology used for fabrication. A typical example is the gilded face mask on the mummy of Ukhhotpe. While the effect has been recognized for more than a century, its cause remained a subject of speculation until recently. Over the years, numerous hypotheses have been advanced to explain the phenomenon, including tarnishing of a debased gold alloy, remanent colloidal gold following selective corrosion and removal of alloying elements such as silver and copper, deposition of organic films, and adventitious or deliberate addition of iron-bearing minerals such as hematite or pyrite to the gold alloy. Notably, Alfred Lucas, one of the foremost early researchers in the study of ancient Egyptian technology, correctly surmised that the vast majority of such colorations resulted from fortuitous tarnishing of silver-bearing gold and also recognized correctly that a smaller group of objects bearing a distinctly different red coloration represented another phenomenon altogether. Tony Frantz, Department of Scientific Research, Deborah Schorsch, Sherman Fairchild Center for Objects Conservation, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, March 2007, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Alfred Lucas, one of the foremost early researchers in the study of ancient Egyptian technology, correctly surmised that the vast majority of such colorations resulted from fortuitous tarnishing of silver-bearing gold and also recognized correctly that a smaller group of objects bearing a distinctly different red coloration represented another phenomenon altogether. The idea that this coloration derives from a corrosion process and not a deliberate patination is prompted partly by the fact that nearly all native gold occurs as an alloy of gold and silver known as electrum, and partly by occurrences of the coloration in what are sometimes observed to be seemingly irregular distributions on the surfaces of objects. The most notable examples of this kind are the gold-leaf decorations on the wood sarcophagus enclosures from the tomb of Tutankhamun, where areas of bright gold leaf are seen juxtaposed against areas of a dark purple coloration along irregular borders that would seem to have no relationship to an intended design. \^/

“Early attempts to analyze the red colorations often were confounded by the extremely small thicknesses of the layers, such that samples obtained by scraping-no matter how judiciously performed-were usually overwhelmed by contamination from the substrate alloy. However, analysis in situ by x-ray diffractometry and x-ray fluorescence spectrometry has provided a rapid and straightforward way of characterizing the films and has shown them typically to be composed of one or more silver-gold sulfides. The species responsible for the predominant reddish purple coloration is most often indicated to be AgAuS, a compound sometimes found in nature as the mineral petrovskaite. In addition, synthetic gold-silver alloys having a silver content between approximately 8 and 11 weight percent silver have been observed to develop red-purple tarnish films identical in appearance and composition to those found on ancient Egyptian silver-gold objects when exposed to sulfide ion for extended periods at elevated temperatures. With increasing silver content and prolonged exposure to sulfide ion, both historical gold-silver objects and modern synthetic gold-silver surfaces develop black tarnishes that include another phase, Ag3AuS2, which also occurs in nature as the mineral uytenbogaardtite. Taken together, the evidence suggests that the red colorations derive largely-as Lucas first conjectured-from fortuitous tarnishing of native electrum having silver-gold compositions appropriate for the formation of the AgAuS phase. \^/

“Red sulfide tarnishes have been identified on historical gold-silver objects from other cultural contexts, including goldwork from the Royal Cemetery at Ur and nineteenth-century European jewelry. That these tarnishes occur predominantly on ancient Egyptian objects likely reflects the high sulfide ion activity associated with the typical contexts of sealed burial chambers as well as the unparted gold-silver alloys used in antiquity. \^/

“As a footnote to the discussion, it should be added that not all red-purple colorations on historical gold objects belong to the sulfide-tarnish group described here. Indeed, as Lucas also observed, a small number of gold pieces from the tomb of Tutankhamun bear a bright, translucent red coloration on their surfaces distinctly different in appearance from the darker and more opaque examples. The origin of the color on these unusual objects has not been determined, but may well reside in the deliberate or accidental addition of iron-bearing compounds to the gold, as synthetic samples of such composition have yielded similar appearing surfaces. There also occur archaeological gold objects that bear reddish accretions of hydrated iron oxides, such as lepidocrocite, presumably deposited as residues from groundwater during burial, as well as the gold masks and other objects from Pre-Columbian South America that exhibit deliberately applied coatings of the red mercuric sulfide mineral cinnabar. Finally, we should mention that the addition of copper to gold in several types of Egyptian objects during the reign of Akhenaten appears to have been done for its rutilizing effect, and that during the Third Intermediate Period copper-rich gold inlays were used with precious-metal inlays of other compositions and hues for the embellishment of large figural bronzes.” \^/

Rewards of Gold and Jewels in Ancient Egypt

“Visible tokens of recognition” were not wanting in Ancient Egypt. As early as during the Middle Kingdom a high officer boasts that “the gold had been given to him as a reward," and this decoration became quite usual under the military government of the 18th dynasty. The biographers of the generals of these warrior kings never forget to relate how many times the deceased received from his lord “the reward of the gold. " Ahmose, son of Abana the Admiral, was seven times “decorated with the gold "; the first time he received the “gold of valour “was as a youth in the fight against the Hyksos, the last time as an old man in the Syrian campaigns of Thutmose I His contemporary, namesake, and fellow-countryman, the general Ahmose, was decorated with the gold by each of the kings under whom he fought, while Amenemheb, the general under Thutmose III, won it six times under this monarch. Each time it was "for valour"; he brought his captives from beyond the Euphrates, he captured Syrian chiefs, or at the head of the most daring he stormed a breach in the wall of a town. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

What was this decoration, the possession of which was so coveted by the distinguished men of all times? It was not one simple decoration like our modern orders, or the "chains of honour" of the 16th century, but it consisted of valuable pieces of jewelry of different kinds. Tiius the gold which was “bestowed in the sight of all men," upon Amenemheb before Kadesh, consisted of a lion, three necklets, two bees, and four bracelets — all worked in the finest gold. Amenhotep I bestowed the “gold “upon the general Ahmose in the form of four bracelets, one vessel for ointment, six bees, a lion, and two hatchets; Thutmose I was still more generous, he gave him four golden bracelets, six golden necklets, three ointment vases of lapislazuli, and two silver clasps for the arms. We see that the value of the metal alone in such a present was very great, and yet the “reward of the gold “was valued more for its symbolic signification than for its intrinsic worth. The richest and the highest in the land vied with each other in order to be rewarded in solemn fashion by the king “before all the people, in the sight of the whole country. " We do not know how the investiture was carried out in the camp, or on the battlefields of those warlike kings, but the remarkable tomb-pictures describing the court life of the heretic king Akhenaten show us how the ceremony was conducted at home in time of peace.

The “divine father Ay “played a prominent part at court in Akhenaten’s new city of Amarna. He had not held high rank under the old hierarchy, but he had risen to be the confidant of the above king, perhaps owing to the active part he had taken in the royal efforts at reformation. He does not seem to have held high religious rank; at court he bore the title of “fan-bearer on the right side of the king," and of “royal truly loved scribe; “he had the care of all the king's horses, but in the hierarchy he never rose higher than the rank of “divine father," which he had held at the beginning of the reformation. His consort Tey helped him much in his advancement at court; she had been the nurse and instructress of the king.

When Ay received the gold for the second time, he was the husband of Tey, and we see, by the manner in which it was awarded him this time, that he was nearly connected with the royal house by his marriage. It was now with royal pomp that the carriages of the distinguished bride and bridegroom were conducted to the palace; companies of runners and fan-bearers escorted them, Syrian and Nubian soldiers formed their bodyguard, and Ay even brought ten scribes with him, to write down the racious words with which his lord would honour him.

Now when Ay and Tey came below the royal balcony, they received an honour far beyond their expectation: the king — Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten — did not call upon his treasurer to adorn them, but he himself and his Great Royal Wife Nefertiti, and his children, wished as a personal favor to bestow the gold decoration upon these faithful servants of his house. Leaning on the colored cushions of the balustrade of the balcony, the monarch threw necklets down to them; the queen, with the youngest princess Ankhesenamun in her arms, threw down chains of gold, and the two older princesses Meritaten and Meketaten, shared in the game and scattered bracelets. Showers of jewels were poured out over Ay and Tey; they were not able to carry them, still less to wear them all. Ay wore seven thick necklets and nine heavy bracelets; the servants had to carry the rest to his home. The crowd broke out into shouts of praise when they saw the graciousness of the monarch, and the boys who had followed Ay danced and jumped for joy. Proudly the happy pair returned home, and the rejoicing which arose there when they came in sight was indeed great. Their servants came joyfully to meet them; they kissed Ay's feet with rapture, and threw themselves in the dust before the gifts of the king. So loud were the shouts of joy that they were heard e\en by the old porters, who were squatting before the back buildings far away from the door. They asked each other in surprise: “What mean these shouts of joy? "

Sources of Gold in Ancient Egypt

Gold was procured from the so-called Arabian desert, the desolate mountainous country between the Nile and the Red Sea. The veins of quartz in these mountains contain gold, and wherever these veins come to the surface, we find, as Wilkinson has already related, that they have been worked in ancient times by the mountain folk, on account of the probability of their containing gold. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

mining map

In two places especially, the quest of these gold-seekers was very successful. The first, which was probably the most ancient source of Egyptian gold, lay in the neighbourhood of Coptos (Qift), and therefore presumably on the great mountain route leading from the sea and from the granite quarries to that point in the valley of the Nile where Coptos was situate. In the Wadi Foachir on this route, old forsaken gold workings have, in fact, been found; these must once have been of considerable importance, for there are still the remains of no less than 1320 workmen's huts. Even if we agree with Wilkinson's judgment as an expert, that these are as late as the Ptolemaic period, yet we may reasonably conclude that the same place was worked in earlier times as well.

The greatest amount of gold, however, came from another place, from the mountains lying much further to the south, mountains belonging geographically to Nubia. Linant and Bonomi discovered one of the mines of this district. Seventeen days' journey from the southern boundary of Egypt, through a waterless, burning, mountainous desert, is a place now called Eshuranib, where the plan of the workings is still plainly to be seen. Deep shafts lead into the mountain, two cisterns collect the water of the winter's rain, and sloping stone tables stand by them to serve for the goldwashing. In the valley are perhaps three hundred stone huts, in each of which is a sort of granite hand-mill, where formerly the quartz dust was crushed. Few places on earth have witnessed such scenes of misery as this spot, now so lonely and deserted that no distant echo reaches our ears of the curses with which the air resounded in those bygone days.

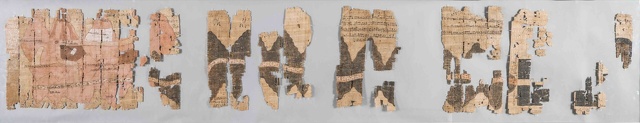

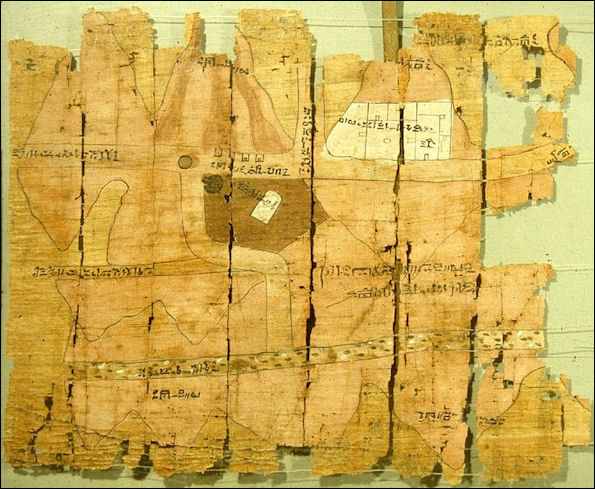

World’s Oldest Geological Map

John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “A 3,100-year-old papyrus scroll, depicting gold mines in ancient Egypt, is probably the oldest surviving geological map and earliest evidence of geological thought, two American researchers have concluded. The scroll, known as the Turin Papyrus and kept at the Egizio Museum in Turin, Italy, is familiar to Egyptologists and historians of cartography as one of the earliest maps from the ancient world. It portrayed roads, quarries, gold mines, a well and some houses. Pink, brown, black and white were used to illustrate mountains and other features. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, November 29, 1988 ==]

"The two geologists — James A. Harrell and V. Max Brown from the University of Toledo in Ohio — examined the map and went into the field to compare it with the site. The area mapped is a wadi, or ravine, in the mountains of Egypt's eastern desert between Qift on the Nile, down from Thebes, and Quseir on the Red Sea. The geologists recognized topographical features from the map, a roadway still in use and the mountains on both sides, shown as cones. Harrell and Brown also noted that the colors were apparently not added for esthetic reasons. In a report at the recent annual meeting of the Geological Society of America in Denver, they said the colors ''correspond with the actual appearance of the rocks making up the mountains.'' ==

Sedimentary rocks in one region, which range in color from purplish to dark gray and dark green, are mapped in black. Pink granitic rocks correspond with the pink- and brown-streaked mountain on the scroll. The scroll notes the locations of the mine and quarry, the gold and silver content of surrounding mountains and the destinations of the roadways. ''The streaks may thus represent the iron-stained, gold-bearing quartz veins that the ancient Egyptians were mining, or they may depict mine tailings,'' Dr. Harrell, who is chairman of the geology department at the University of Toledo, told the New York Times. ==

Dr. Harrell and Dr. Brown made their discovery while conducting research for an atlas of the stones used in ancient Egyptian sculptures. Dr. Harrell told the New York Times: ''In order for it to be a geological map, it must show distribution of different rock types. Secondarily, it should indicate the location of geological features like mountains and valleys. In both regards, the scroll qualifies, and reminds us of modern geologic mapping.'' The scroll map was apparently prepared around 1150 B.C. in the reign of Ramses IV. William Smith, an English surveyor, is generally credited with initiating modern geologic mapmaking in 1815. ==

Goldmine Papyrus

The World’s Oldest Geological Map is part of the Goldmine Papyrus, which dates to 1151–1145 B.C. and measures 2.7 meters (9 feet) by 0.4 meters (1.3 feet). Found at Deir el-Medina, home of the New Kingdom craftsmen who worked in the Valley of the Kings, and created by Amennakhte, the chief scribe of the royal necropolis, the papyrus depicts a dry riverbed called the Wadi Hammamat in Egypt’s eastern desert. The wadi had been used for quarrying and mining for centuries, and as a route connecting the Nile Valley to the Red Sea for millennia. [Source:Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2019]

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: No map would have been needed for general travel, according to Egyptologist Andreas Dorn of Uppsala University and linguist Stéphane Polis of the University of Liège. Instead, the papyrus was created as a commemorative record of a pharaonic expedition, perhaps during the reign of Ramses IV (r. ca. 1153–1147 B.C.), to a bekhen-stone quarry. Bekhen-stone, or greywacke, was prized for use in high-quality sculptures. To distinguish types of stone, Amennakhte employed dark brown to represent bekhen-stone, pink for deposits of granite and gold, and spots for alluvial deposits.

“The scribe also included quarried bekhen-stone blocks with their measurements, as well as roads and directions in hieroglyphs, such as “road leading to the sea. ” Amennakhte also drew natural and built landmarks including small trees, bushes, and a well, along with a monument to Seti I (r. ca. 1294–1279 B.C.) and a temple to the god Amun, both illustrated in white at the far left. “Amennakhte definitely had experience visualizing complex structures, as he was also responsible for drawing tombs. He was able to represent topographical information by flattening out such things as roads and the natural environment,” says Polis. “This unique document mixes geographical and geological information in a way that anticipates many of our modern mapmaking practices. ”

Precious Metals from Tell Basta

Tell Basta

Diana Craig Patch of The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “In 1906, workmen constructing a railway across the Egyptian delta uncovered two hoards of metal objects, including vessels, jewelry and silver ingots, buried at Tell Basta (near modern Zagazig). The caches had been hidden close to the ancient temple dedicated to the feline goddess Bastet. Several vessels in bear the cartouches of Queen Tawosret, the last ruler of Dynasty 19, and those inscriptions, along with the granulated decoration on the boss, suggest most pieces were manufactured between 1295 and 1186 B.C. The lion handle on one jug and the mixture of Near Eastern motifs with traditional Egyptian scenes on the bowl, however, indicate a slightly later date for some pieces, and the Third Intermediate Period (ca. 1070–713 B.C.) must be considered. [Source: Diana Craig Patch, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The hoards contain a mixture of vessel forms covering a period of time with decorative motifs common to the circum-Mediterranean region, that is, widely found in many cultures along the Mediterranean coast. Some pieces seem not to be Egyptian, such as Canaanite-style earrings now in Cairo. This mixture of styles and motifs suggests that the objects may have been discarded temple equipment that had been collected for reuse. The partially recycled nature of some pieces—bits and pieces are missing—along with the hoards' location near a temple argue that a temple workshop owned the material. We know that craftsmen were using old or looted pieces to create new objects some time after 1000 B.C.\^/

“Vessels made from precious metals were created for use in only a few settings, the temple or the tables of royal and noble households, where money and status permitted more opulent materials to replace the customary ceramic or bronze. Gold was the easier of the two precious metals for Egyptians to acquire, since nearby Nubia had significant deposits. Silver had to be imported, most likely from Greece or Anatolia, and as a result was an uncommon material in Egypt, although increasingly larger amounts were available to craftsmen by the late New Kingdom (ca. 1250 B.C.). Few gold and silver containers survive into modern times. Rare in antiquity, most were melted in the past to reuse the metal for new projects after the original item no longer had a relevant social or ideological value. Thus, the Tell Basta hoards were exceptional finds. \^/

“The long open form called a situla was a drinking vessel, while jars, jugs, and bowls were used to serve food and drink. The hoards had several strainers designed to make the thick beer and wine more palatable. Vessels bearing representations of deities most certainly were dedicatory items to the temple's cult.” \^/

Nubian Gold Mines

We do not know for certain where the Nubian gold mines were located, or to which the route of Redesieh was to lead; the inscription does not allude to the mines of Eshuranib, for, apart from other reasons, the king was endeavoring at the same time to open a way to this latter district also. We learn this from an inscription of Ramses II. This king, "at whose name the gold comes forth from the mountain," was at one time at Memphis, and while thinking of the countries “from which gold was brought, he meditated plans as to how wells might be bored on the roads which were in need of water. For he had heard there was indeed much gold in the country of 'Ekayta, but the way thereto was wholly without water. When any of the gold-washers went thither, there were only the half of them who arrived there; they died of thirst on the way, together with the donkeys, which they drove before them, and they found nothing to drink, neither in going up nor in coming down, no water to fill the skins. Therefore no gold was brought from this country, because of the scarcity of water.

“Then spake his Majesty to the lord high treasurer, who stood near him: ' Call then the princes of the court, that his Majesty may take counsel with them about this country,' and immediately the princes were conducted into the presence of this good god, they raised their arms rejoicing, and praised him and kissed the earth before his beautiful countenance. Then it was recounted to them how the matter stood with this country, and their counsel was asked as to how a well should be bored on the road leading thither. "

Two wonderful papyri, famous as the oldest maps in the world, relate to the gold mines of the two last-named kings. " One papyrus, which is only partially preserved, represents the gold district of the mountains where such as the mines situate to the east of Coptos, and belongs to the time of Ramses II. I cannot say what place is represented in the other, which may be seen in the accompanying illustration. It represents, as we see, two valleys running parallel to each other between the mountains, one of these valleys, like many of the larger wadis of the desert, seems to be covered with underwood and blocks of stone; a winding crossway valley unites the two. The pointed mountains (the drawing of which strikes us as particularly primitive) contain the mines; that marked B bears the superscription “gold mine," whilst by the one marked A may be read “these are the mountains where the gold is washed; they are also of this red color “(they were represented red on the papyrus). The valley M and the pass N are “routes leading to the sea," the name of the place, which is reached through the large valley marked O, or the adjoining one marked D, is unfortunately illegible. The mountain C, on which there are great buildings, bears the name of the “pure mountain "; on it was a sanctuary to Amon; the small houses marked II belonged, if I read aright, to the gold miners. Finally the water tank K, with the dark cultivated ground surrounding it, represents "the well of King Seti I. ": the same king who erected the great stele J, probably in remembrance of the boring of this well.

A certain poetic halo surrounded gold-digging in the mountains — we read indeed in an inscription in a mine: “gold is the body of the gods, and Ra said, when he began to speak: ' my skin is of pure electron. ' “This was not the case however with the prosaic copper mines, though they were of course of more national importance; in the inscriptions relating to them there was no boasting about their daily yield. This is also the reason that the inscriptions in those mines, which were presumably copper mines, scarcely ever mention the copper; ' but speaknrather of what is really a mere by-product of the same, the precious stone, V\ ¥ v\, mfaket such as malachite, as the yield of the mine.

Journey from the Nubian Gold Mines

Texts are still extant describing the working of the Nubian goldmines. They picture to us the difficulties of mining in the desert so far from the Nile valley — each journey became a dangerous expedition, owing to want of water and to the robber nomads. When King Senusret I. had subjected Nubia, Ameny, our oft-mentioned nomarch, relates that he began immediately to plunder the gold district. “I went up," he says, “in order to fetch gold for his Majesty, King Senusret I. (may he live always and for ever). I went together with the hereditary prince, the prince, the great legitimate son of the king, Ameny (life, health, and happiness!) and I went with a company of 400 men of the choicest of my soldiers, who by good fortune arrived safely without loss of any of their number. I brought the gold I was commissioned to bring, and was in consequence placed in the royal house, and the king's son thanked me. " The strong escort, which in this case was required mainly for the protection of the gold, shows the insecurity of the road. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Later, During the New Kingdom, when Nubia was an Egyptian province, the road seems to have been safer, at any rate the inscriptions of the 19th dynasty emphasise only the other difficulty, the want of water. Thus an inscription in the desert temple of Redesieh, dated the 9th year, the 20th Epiphi, relates that King Seti I. “desired to see the gold mines from which the gold was brought. When his Majesty had now ascended . . . he stood still in the way, in order to consider a plan in his own mind. He said: ' How bad is this waterless way! What becomes of those who travel along it? . . . Wherewith do they cool their throats? Wherewith do they quench their thirst } . . . I will care for them and give them this necessary of life, that they may be grateful to my name all the years that shall come. ' . . . When his Majesty had spoken these words in his heart, he traveled through the mountains, and sought a fitting place. . . . The god moreover guided him in order to fulfil his request. Then were stone-masons commissioned to dig a well on the mountain, so that the weary might be comforted, and those scorched by the summer heat refreshed. Behold, this place was then erected to the great name of King Sety, and the water ov-erflowed in such abundance as if it came from the hollow of the two cave-springs of Elephantine. "

When thus the well was finished, his Majesty resolved to establish a station there also, “a town with a temple. " The “controller of the royal works," with his stone masons, carried out this commission of the monarch, the temple was erected and consecrated to the gods; Ra was to be worshipped in the holy of holies, Ptah and Osiris in the great hall, whilst Horus, Isis, and the king himself, formed the “divine cycle “of the temple. “And when this monument was now finished, when it had been decorated and the paintings were completed, his Majesty himself came thither to worship his fathers the gods. "

Gold in Miners in Nubia

The people who here dug out the “gold of Nubia “for the Egyptian kings, who endured for a shorter or longer period the frightful heat of these valleys, were captives; the Wadi Eshuranib was the Egyptian Siberia. Chained, with no clothes, guarded by barbarian soldiers speaking a language unknown to them, these unfortunate wretches had to work day and night without hope of deliverance. No one cared what became of them; the stick of the pitiless overseer drove even the sick, the women, and the old men to work, till, exhausted by labor, want, and heat, death at last brought them their longed-for release. Thus it was in Greek times, and as there is no reason to believe that the Pharaohs were more humane than the Ptolemies, we may accept the terrible picture Diodorus draws '" as applying also to the times with which we are concerned — so much the more as we cannot conceive any way in which these mines could be worked without this reckless expenditure of life. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Diodorus also describes to us the procedure followed in the working of these mines, and his account is corroborated by modern discoveries. The shafts follow the veins of quartz, for this reason winding their way deeply into the heart of the mountain. The hard stone was first made brittle by the action of fire, then hoed out with iron picks. The men who did this hard work toiled by the light of little lamps, and were accompanied by children, who carried away the bits of stone as they were hewn out. This quartz was then crushed in stone mortars into pieces about the size of lentils; women and old men then pounded it to dust in mills. This dust was next washed on sloping tables, until the water had carried off all the lighter particles of stone; the fine sparkling particles of gold were then collected, and together with a certain amount of lead, salt, and other matters, kept in closed clay smelting-pots for five whole days. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Thus far Diodorus relates; the procedure of more ancient times was probably the same. Formerly however the gold was not always smelted on the spot, but was brought in bags to Egypt as at the present day. For commercial purposes gold was as a rule formed into rings, which, judging from the representations, seem to have been of very variable thickness, with a uniform diameter of about five inches. Naturally these rings were not taken on trust, and whenever they were paid over, we see the master-weigher and the scribes busy weighing them and entering the ascertained weight in their books. " We hear of enormous sums changing hands in this way. Under Thutmose III. an official receives a "great heap “of electron, which, if w-e may believe the inscription, weighed 36,392 uten such as 331 I kilos 672 grammes, which would amount to about 66 cwt. This quantity of gold would now be worth about;5 00,000; therefore in electron, which as we have seen consisted of an amalgam of two-fifths gold and three-fifths silver, this mass would be worth at least 200,000. Moreover, During the New Kingdom, various kinds of gold were distinguished in commerce, such as the "mountain gold," and the "good gold," the “gold of twice," and the “gold of thrice," the “gold of the weight," and the "good gold of Katm such as the nriD of Semitic countries.

Has the Source of Nubian Gold Been Discovered

In 2007, archaeologists announced the discovery of an ancient gold-processing and panning camp along the Nile River in the northern Sudan that they described as the first physical evidence of where Egypt obtained its gold stashes from Nubia. The riverside camp about 1,300 kilometers (800 miles) south of Cairo, was first investigated but “mentioned only in passing” during the 1960s. The archaeologists think non-Egyptians called Kushites, who ruled the region, gathered gold at the site from about 2000 B.C. to 1500 B.C. and used it to trade with Egypt. “Based on what we’ve found, the kingdom of Kush was significantly larger and more powerful than anyone thought,” said Geoff Emberling, an archaeologist at the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute and co-leader of the expedition. Emberling explained most other clues of the Kushite’s reach have been inferred from written Egyptian records. [Source Dave Mosher, Live Science, June 19, 2007]

Bruce Williams, also an archaeologist at the Oriental Institute and expedition co-leader, agreed. “If Kushites were processing gold way out here, more than 200 miles from their capital city Kerma, there had to have been good logistics and discipline,” he said of the site at Hosh el-Guruf. “You can only imagine the chaos of an unattended gold mining operation.”

Dave Mosher wrote in Live Science: To the untrained eye, the gold-processing center is a field of rocks about 150 feet from the Nile’s banks. But closer inspection revealed 55 two-foot grindstones used to crush gold ore, the team said. Once macerated into dust and gold flakes, camp workers may have sifted out the bounty using the Nile’s waters. Emberling thinks powerful leaders in Kerma, located 225 miles downstream, demanded the rural gold product in a customary but unequal exchange for trinkets and supplies. “The process probably went like this: ‘We send you the trinkets, you send us the bags of gold and we give you more status,’” Emberling said.

The archaeologists think the Kushite rulers in Kerma ultimately used the gold as leverage against the powerful Egyptians, who eventually took over the weakened Nubian kingdom with military might by 1500 B.C.“The kingdom of Kush and the Egyptians were close trading buddies, but Egypt had three classic enemies: the Asiatics, the Libyans and the Kushites,” Emberling said. “Their cultures clashed, and the Kushites had more resources available to them, which the Egyptians wanted.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024