METALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

King Tut's iron dagger

Bronze tools were widely used and texts refer ro them often. Egyptians made several kinds of bronze. Texts from the New Kingdom refer to “black bronze," and the “bronze in the combi such as a six-fold alloy.” It is impossible to decide at how early a period bronze was employed by artists in the making of statues. A small funerary figure of King Ramses II is one of most ancient example of a bronze statuette. It is cast hollow, and is beautifully chased. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The main resource that Egypt had to trade was gold. An envious Assyrian king wrote: “Gold in your country is dirt: “one simply gathers it up.” The mines that ancient Egyptians used to get gold, emeralds and silver are all depleted now.

Iron was made around 1500 B.C. by the Hitittes. About 1400 B.C., the Chalbyes, a subject tribe of the Hitittes invented the cementation process to make iron stronger. The iron was hammered and heated in contact with charcoal. The carbon absorbed from the charcoal made the iron harder and stronger. The smelting temperature was increased by using more sophisticated bellows. About 1200 BC, scholars suggest, cultures other than the Hittites began to possess iron. The Assyrians began using iron weapons and armor in Mesopotamia around that time with deadly results, but the Egyptians did not utilize the metal until the later pharaohs.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MINING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PRECIOUS METALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: GOLD, SILVER, MINING, SOURCES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

GEM STONES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Egyptian Metalworking and Tools” by Bernd Scheel (1999) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Metallurgy” by H. Garland and C. O. Bannister (2015) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Technology and Innovation” by Ian Shaw (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Copper in Ancient Egypt: Before, During and After the Pyramid Age (C. 4000 – 1600 BC) by Martin Odler (2023) Amazon.com;

“Proceedings of the First Intl. Conf. On Ancient Egypt Mining and Metallurgy”

by Supreme Council of Antiquities (2005) Amazon.com;

“Gold and Gold Mining in Ancient Egypt and Nubia: Geoarchaeology of the Ancient Gold Mining Sites in the Egyptian and Sudanese Eastern Deserts” by Rosemarie Klemm and Dietrich Klemm (2012) Amazon.com;

“Nubian Gold: Ancient Jewelry from Sudan and Egypt” by Peter Lacovara and Yvonne J. Markowitz (2019) Amazon.com

“The Bronze Age: A History from Beginning to End” by Hourly History (2024) Amazon.com;

“Tin in Antiquity: Its Mining and Trade Throughout the Ancient World with Particular Reference to Cornwall” by R.D. Penhallurick (2008) Amazon.com;

“Anatolia and the Bronze Age: The History of the Earliest Kingdoms and Cities that Dominated the Region” by Charles River Editors (2023) Amazon.com;

Ancient Egyptian Metallurgy

Early tools were made from copper and later bronze. Egyptian bronze tended to be around 88 percent copper and 12 percent tin. Iron was introduced by the Hittites in the 13th century but wasn't common until the 6th or 7th century B.C.

A wide variety of copper tools, fish hooks and needles were made. Chisels and knives lost their edge and shape quickly and had be reshaped with some regularity or simply thrown out. In the Old Kingdom (2700 to 2125 B.C.) there was only copper. Copper-making hearths have been found near the pyramids. Reliefs found nearby show Egyptians gathering around a fire smelting copper by blowing into long tubes with bulbous endings.

Knives tended be made from bronze. They were considerably sharper than copper knives. The sharpest knives of all were made of flaked obsidian. A wide variety of stone tools were also used, including pick axes and hammers.

Sculptures made of copper, bronze and other metals were cast using the lost wax method which worked as follows: 1) A form was made of wax molded around a pieces of clay. 2) The form was enclosed in a clay mold with pins used to stabilize the form. 3) The mold was fired in a kiln. The mold hardened into a ceramic and the wax burns and melted leaving behind a cavity in the shape of the original form. 4) Metal was poured into the cavity of the mold. The metal sculpture was removed by breaking the clay when it was sufficiently cool.

Metalworking in Ancient Egypt

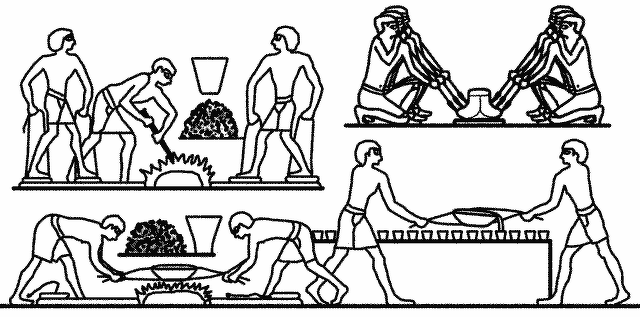

One tomb image that appears to represent the smelting of precious metal shows workmen are sitting before the fire blowing through tubes into the flame; in one case the tube has the same point as is seen in the older pictures. These metal points,' which are evidently intended to concentrate and increase the draught of air, are also to be seen on the tubes of the bellows represented in a tomb of the New Kingdom. ' These bellows consist of two bags, apparently of leather, in each of which a tube is fastened. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

A workman stands with one foot on each bag; if he presses the left one down, he raises the right leg at the same time, and draws up the right-hand bellows with a string. Two pair of these bellows are being used for an open coal fire, and the glow they produce is so strong that the workmen are obliged to use long wire rods in order to take off the little crucible. When a smaller fire only was needed, it might be lighted in a deep clay bowl surrounded by metal plates ' to protect it from draught; this fire could also be fanned by blowing through a tube.

The methods of metalworking, the melting, forging, soldering, and chasing of metal, are unfortunately rarely to be found in any representation. We are confronted here by the same curious fact that the tomb pictures, whilst showing a predilection for treating of much that is unimportant, almost ignore an art which was not only much practised, but also most highly developed. The frequent mention of workers in metal gives us a truer conception of the importance of this industry than the few representations that exist in the tombs. The workers in bronze with their chiefs, but above all the goldsmiths, are often mentioned, and were apparently held in great esteem.

Bronze Tools in Ancient Egypt

bronze knives used in mummification

André Dollinger wrote in his Pharaonic Egypt site: “Bronze implements found at Gurob, 18th-19th dynasty Bronze was a great improvement on copper. The oldest real bronze found in Egypt dates to the 4th dynasty and consists of 90 percent copper and 10 percent additional metals, which is about the best combination. Brittler than pure copper, it was easier to cast and could be hardened by repeated heating and hammering. [Source: André Dollinger, Pharaonic Egypt site]

“The first bronze tools were not the result of a deliberate attempt at improving the metal, but of the natural mix of copper and other metals in the smelted ore, in Egypt mostly arsenic. This poisonous metal was replaced during the second millennium by tin.

“Adding more tin results in a harder alloy which cannot be worked cold, but has to be heated to temperatures of between 600 and 800 °C. Tools and weapons were generally made of this harder bronze, while softer metal was preferred for casting statues and vessels which were subsequently hammered and engraved. Bronze tools found at Gurob: 1) Chisel with tang; 2) Chisels; 3) Adze blade; 4) Hatchet]; 6) Rasp; 7) Hatchet; 8) Nails; 9) Arrow head; 10) Lance head; 11) Knife of unknown use; 12) Switching blade; 13) Barbless fishing hooks,

See Separate Article: TOOLS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: MADE OF STONE, METAL AND METEORIC IRON africame.factsanddetails.com ; BRONZE AGE (3500-1200 B.C.) factsanddetails.com

Sources of Ancient Tin in Afghanistan and Turkey

Tin is needed to make bronze. One of the most enduring mysteries about ancient technology, John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “is where did the metalsmiths of the Middle East get the tin to produce the prized alloy that gave the Bronze Age its name. Digging through ruins and deciphering ancient texts, scholars found many sources of copper ore and evidence of furnaces for copper smelting. But despite their searching, they could never find any sign of ancient tin mining or smelting anywhere closer than Afghanistan. Sumerian texts referred to the tin trade from the east (thought to be Afghanistan). In the 1970s, Russian and French geologists identified several ancient tin mines in Afghanistan, where tin appears to be abundant . For many years that discovery seemed to resolve the issue of Mesopotamia's tin source. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, January 4, 1994]

It seemed incredible though that such an important industry could have been founded and sustained with long-distance trade alone to places like Afghanistan. But where was there any tin closer to home? After systematic explorations in the central Taurus Mountains of Turkey, an archeologist at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago has found a tin mine and ancient mining village 60 miles north of the Mediterranean coastal city of Tarsus. This was the first clear evidence of a local tin industry in the Middle East, archeologists said, and it dates to the early years of the Bronze Age.

The findings changed established thinking about the role of trade and metallurgy in the economic and cultural expansion of the Middle East in the Bronze Age. In an announcement made in January 1994, Dr. Aslihan Yener of the Oriental Institute reported that the mine and village demonstrated that tin mining was a well-developed industry in the region as long ago as 2870 B. C. She analyzed artifacts to re-create the process used to separate tin from ore at relatively low temperatures and in substantial quantities."Already we know that the industry had become just that — a fully developed industry with specialization of work," Dr. Yener told the New York Times, "It had gone beyond the craft stages that characterize production done for local purposes only."

See Separate Article: MINING, BRONZE, GOLD AND TIN IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA factsanddetails.com

Copper in Ancient Egypt

A wide variety of copper tools, fish hooks and needles were made. Chisels and knives lost their edge and shape quickly and had be reshaped with some regularity or simply thrown out. In the Old Kingdom (2700 to 2125 B.C.) there was only copper. Copper-making hearths have been found near the pyramids. Reliefs found nearby show Egyptians gathering around a fire smelting copper by blowing into long tubes with bulbous endings.

André Dollinger wrote in his Pharaonic Egypt site: “Copper may have been the first metal to be worked in Egypt, even before the metallic gold. The ores had a 12 percent copper content and given the scarcity of fuel and the difficulties of transportation one may well marvel at the fact, that they succeeded at extracting copper at all. In the beginning it was probably worked cold. In early Egyptian graves copper ornaments, vessels and weapons have been found as well as needles, saws, scissors, pincers, axes, adzes, harpoon and arrow tips, and knives. [Source: André Dollinger, Pharaonic Egypt site]

Egyptian metal workers

Marks made by a copper saw are visible in a piece of basalt paving found near Khufu’s pyramid on the Giza Plateau. Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Although nowhere to be seen in the finished product, massive amounts of copper were essential to building the monument. Copper picks were used to quarry the stone. Copper saws were used to cut it, and experiments have shown that an inch of metal was lost from blades for every one to four inches of stone cut. While preparing the stone blocks for use in the pyramid, workers smoothed their surfaces with copper chisels the width of an index finger. The immense quantity of copper consumed by the construction project — not to mention the other pyramids and monumental buildings that preceded and followed it — led to an urgent search for sources of the metal. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022]

Some copper was extracted from the Eastern Desert, between the Nile Valley and the Red Sea, but the major copper mines were across the sea in the southern portion of the Sinai Peninsula. The most efficient way to access these mines was by boat. Until just over a decade ago, the earliest known Red Sea harbor was at Ayn Sukhna, which was excavated starting in 2001 by a team led by Egyptologist Pierre Tallet of the University of Paris-Sorbonne. The harbor at Ayn Sukhna appears to have been used intermittently for more than a millennium to access the Sinai, starting during the reign of Khafre (r. ca. 2597–2573 B.C.), Khufu’s son. Then, in 2008, Tallet’s team relocated a previously known but little understood coastal site at Wadi el-Jarf, some 60 miles south of Ayn Sukhna, and found that it had served as a harbor for around 50 to 70 years in the 4th Dynasty (ca. 2675–2545 B.C.), including the reign of Khufu. It is the earliest known harbor in the world.

See Separate Article: COPPER IN ANCIENT EGYPT: USES, SOURCES, MINING africame.factsanddetails.com

Iron Tools in Ancient Egypt

Iron was made around 1500 B.C. by the Hitittes. About 1400 B.C., the Chalbyes, a subject tribe of the Hitittes invented the cementation process to make iron stronger. The iron was hammered and heated in contact with charcoal. The carbon absorbed from the charcoal made the iron harder and stronger. The smelting temperature was increased by using more sophisticated bellows. About 1200 B.C., scholars suggest, cultures other than the Hittites began to possess iron. The Assyrians began using iron weapons and armor in Mesopotamia around that time with deadly results, but the Egyptians did not utilize the metal until the later pharaohs.

André Dollinger wrote in his Pharaonic Egypt site: “Rare meteoritic iron has been found in tombs since the Old Kingdom, but Egypt was late to accept iron on a large scale. It did not exploit any ores of its own and the metal was imported, in which activity the Greeks were heavily involved. Naukratis, an Ionian town in the Delta, became a centre of iron working in the 7th century BCE, as did Dennefeh. [Source: André Dollinger, Pharaonic Egypt site,]

“Iron could not be completely melted in antiquity, as the necessary temperature of more than 1500°C could not be achieved. The porous mass of brittle iron, which was the result of the smelting in the charcoal furnaces, had to be worked by hammering in order to remove the impurities. Carburizing and quenching turned the soft wrought iron into steel.

“Iron implements are generally less well preserved than those made of copper or bronze. But the range of preserved iron tools covers most human activities. The metal parts of the tools were fastened to wooden handles either by fitting them with a tang or a hollow socket. While iron replaced bronze tools completely, bronze continued to be used for statues, cases, boxes, vases and other vessels.”

Oldest Iron in Ancient Egypt from Meteorites

Nine small, cylindrical beads found in two 5,000-year-old grave pits from a cemetery near the Nile in northern Egypt were found to have been made of meteoric iron. Archaeology magazine reported: Scientists examined one of the iron beads, first identified in 1911, and found that it is high in nickel and has a crystal structure called a Widmanstätten pattern — both indicative of extraterrestrial origin. The beads predate ancient Egyptian iron smelting by at least 3,000 years. Iron seems to have been a rare — and therefore high-status — material in pre-Dynastic Egypt. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2013]

The Guardian reported: “Although people have worked with copper, bronze and gold since 4,000 B.C.. The beads described above were found to have been beaten out of meteorite fragments, and also a nickel-iron alloy. “As the only two valuable iron artifacts from ancient Egypt so far accurately analysed are of meteoritic origin,” Italian and Egyptian researchers wrote in the journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science, “we suggest that ancient Egyptians attributed great value to meteoritic iron for the production of fine ornamental or ceremonial objects”. [Source: The Guardian, June 2, 2016]

“The researchers also stood with a hypothesis that ancient Egyptians placed great importance on rocks falling from the sky. They suggested that the finding of a meteorite-made dagger adds meaning to the use of the term “iron” in ancient texts, and noted around the 13th century B.C., a term “literally translated as ‘iron of the sky’ came into use … to describe all types of iron”. “Finally, somebody has managed to confirm what we always reasonably assumed,” Thilo Rehren, an archaeologist with University College London, told the Guardian. “Yes, the Egyptians referred to this stuff as metal from the heaven, which is purely descriptive,” he said. “What I find impressive is that they were capable of creating such delicate and well manufactured objects in a metal of which they didn’t have much experience.” The researchers wrote in the new study: “The introduction of the new composite term suggests that the ancient Egyptians were aware that these rare chunks of iron fell from the sky already in the 13th [century] B.C., anticipating Western culture by more than two millennia.”

See Separate Article: EARLIEST IRON AND STEEL: METEORITES, HITTTIES, AFRICA, SPAIN AND SRI LANKA factsanddetails.com ; EARLY IRON AGE africame.factsanddetails.com

Dagger in Tutankhamun's Tomb: Made from a Meteorite

On the dagger found in the tomb of King Tutankhamun (King Tut) , Jay Bennett wrote in National Geographic: The knife has a gold hilt with stone and glass inlays, a pommel of rock crystal, and a gold sheath with elaborate designs. Found in the wrappings around the mummy’s right thigh, the dagger was “something that he would need in the afterlife to fight against the demons, or whatever dangers the afterlife has, because the afterlife is a dangerous place,” Almansa-Villatoro says. “It’s also a marker of status.” Tut’s dagger is one of the most expertly wrought objects of its kind, but evidence of ancient cultures using meteoritic iron has been found elsewhere in the region and the world. A likely meteoritic iron dagger from a royal tomb at Alacahöyük in Turkey predates Tut’s knife by about a thousand years. [Source: Jay Bennett, National Geographic, May 9, 2023]

In 2016, scientists announced in the in the journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science. that an iron dagger entombed with King was likely made with iron from a meteorite. The iron dagger was buried with Tutankhamun centuries before iron smelting emerged in Egypt. Academics had long debated whether the iron for the blade was smelted elsewhere and imported as a gift, or came from a metallic meteorite. Tutankhamun was buried around 1352 B.C.); the smelting technologies that allowed people to heat iron emerged around 1200 B.C. Using portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry, physicists have determined, based on the blade’s composition, that it was likely made from meteoritic iron, which the Egyptians called bia-n-pt or, literally, “iron from the sky.” [Source: Samir S. Patel Archaeology magazine, November-December 2016]

The Guardian reported: “In 1925, archaeologist Howard Carter found two daggers, one iron and one with a blade of gold, within the wrapping of the teenage king... The iron blade, which had a gold handle, rock crystal pommel and lily and jackal-decorated sheath, has puzzled researchers... ironwork was rare in ancient Egypt, and the dagger’s metal had not rusted. “Italian and Egyptian researchers analysed the metal with an x-ray fluorescence spectrometer to determine its chemical composition, and found its high nickel content, along with its levels of cobalt, “strongly suggests an extraterrestrial origin”. They compared the composition with known meteorites within 2,000km around the Red Sea coast of Egypt, and found similar levels in one meteorite. That meteorite, named Kharga, was found 150 miles (240km) west of Alexandria, at the seaport city of Mersa Matruh, which in the age of Alexander the Great – the fourth century B.C. – was known as Amunia. [Source: The Guardian, June 2, 2016 */]

See Separate Article: TUTANKHAMUN’S TOMB: LAYOUT, CONTENTS, TREASURES, METEORIC IRON africame.factsanddetails.com

Oldest References to Iron in Ancient Egypt

Jay Bennett wrote in National Geographic: Inside a 4,400-year-old royal tomb in Saqqara, about 15 miles south of Cairo, I studied the walls searching for a particular symbol. The symbol I was trying to find looks something like a bowl with a horizontal line just beneath the brim, as if it were filled with water. Egyptologist Victoria Almansa-Villatoro, A scholar of Old Kingdom texts with the Harvard Society of Fellows, scanned the hieroglyphs with two extended fingers. [Source: Jay Bennett, National Geographic, May 9, 2023]

This burial place belonged to Unas, the last ruler of the 5th dynasty from the 24th century B.C. The passages on the walls, called spells by Egyptologists, were intended to guide the deceased king through the perils of the afterlife. They are the oldest such writings, collectively known as the Pyramid Texts. Almansa-Villatoro’s fingers froze over a column of symbols next to the passageway to Unas’s sarcophagus. “There you go,” she whispered excitedly, pointing to the U-shaped marking.

The symbol, Almansa-Villatoro’s research suggests, was used to refer to iron — a remarkable thing for Egyptians to write about at that time. It would be roughly a thousand years before humans learned to reliably smelt iron. But there is another source of the metal: meteorites. In most cases, it isn’t known whether these cultures understood where meteorites came from. In the tomb of Unas, however, the funerary texts tell of metal in the sky, suggesting Egyptians may have not only recognized the phenomenon of falling iron but also incorporated it into their mystical beliefs.

Almansa-Villatoro broke down the semantics of the sentence for me. She pointed out an arched symbol meaning “sky” and a teardrop-shaped glyph indicating “metals. ” Together with the bowl symbol, these hieroglyphs refer to a metal belonging to the sky, she explained. “Unas seizes — grabs — the sky and splits its iron,” she translated.

This line describes the journey of Unas into the divine realm of the sky. The exact meaning is obscure, but Almansa-Villatoro argues the passage reflects a belief that the sky is a great water-filled iron basin from which rain and metal sometimes fall. To reach the afterlife, the Pyramid Texts tell us, the king must sail across this celestial domain.

The texts, which also appear in the tombs of later rulers, include other equally abstruse references. “The iron door in the starry sky is pulled open,” reads one line, according to Almansa-Villatoro’s translations. They also tell of an “egg” of iron, a possible metaphor for the womb of the Egyptian sky goddess Nut. “He will break the iron after he has split the egg,” another line says. “Iron has all these cosmological connotations with creation and, therefore, resurrection,” Almansa-Villatoro says. To split the iron egg of the sky is to return to the womb to be reborn.

Iron — Ancient Egypt's Metal from the Sky

Jay Bennett wrote in National Geographic: At the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, I admired two iron objects found with Tutankhamun’s mummified remains that were recently confirmed as meteoritic. One is a pendant of the Eye of Horus hanging on a gold alloy bracelet, discovered near Tut’s right rib cage in the wrappings. The other is a small charm in the shape of a headrest, like the full-size ones made of wood that the Egyptians used when they slept. It was found in the back of Tut’s funerary mask. These headrest amulets served as symbols of rebirth. The image of a round head on a curved headrest evoked the rising sun, the god Re, who was birthed by the sky goddess Nut each morning and swallowed by her each night. [Source: Jay Bennett, National Geographic, May 9, 2023]

I couldn’t help but wonder if the people who made these talismans knew where the otherworldly material came from. While carefully filing the lines of Horus’s eyebrow, did the artisan think about how the metal had come into his hands from the realm of the gods? When the small bit of iron was bent into the shape of a headrest, did the curved amulet remind the metalworker of the great basin in the sky?

We will never know, but we do know that descriptions of metal in the sky would endure in Egyptian writings for thousands of years. The funerary spells in the Pyramid Texts evolved into the Coffin Texts, painted on caskets inside and out. “I know the Field of Reeds of Re,” reads one line repeated on several coffins, referring to a region in the sky. “The wall that goes around it is of iron. ” By the 13th century B.C., a more direct way of writing “metal of the sky” came into use. Funerary spells then were written on papyrus and today are known as the Book of the Dead. In one spell, a great fishing net is described — a barrier the deceased must navigate in their journey to the afterlife. “Do you know that I know the name of its weights?” the Book of the Dead intones. “It is the iron in the midst of the sky. ”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024