COPPER TOOLS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

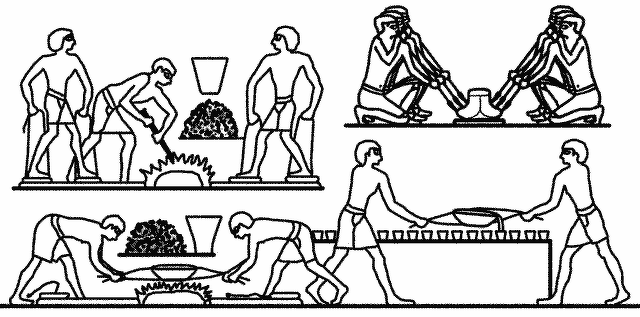

A wide variety of copper tools, fish hooks and needles were made. Chisels and knives lost their edge and shape quickly and had be reshaped with some regularity or simply thrown out. In the Old Kingdom (2700 to 2125 B.C.) there was only copper. Copper-making hearths have been found near the pyramids. Reliefs found nearby show Egyptians gathering around a fire smelting copper by blowing into long tubes with bulbous endings.

André Dollinger wrote in his Pharaonic Egypt site: “Copper may have been the first metal to be worked in Egypt, even before the metallic gold. The ores had a 12 percent copper content and given the scarcity of fuel and the difficulties of transportation one may well marvel at the fact, that they succeeded at extracting copper at all. In the beginning it was probably worked cold. In early Egyptian graves copper ornaments, vessels and weapons have been found as well as needles, saws, scissors, pincers, axes, adzes, harpoon and arrow tips, and knives. [Source: André Dollinger, Pharaonic Egypt site]

“This wide array of tools made of a metal difficult to cast and even with tempering too soft to be of use with any but the softest stone and wood shows the urgent need people felt for tools more flexible than what could be made of wood and stone.” Much of the copper used in Egypt was mined in the Sinai.

“Pure copper (like silver or gold) has a hardness factor of 2.5 to 3 on the Moh scale which is just about the same as limestone's. Naturally occurring copper is somewhat harder due to metallic impurities. Thanks to tempering, copper chisels and saws could be used to work freshly quarried limestone from the 4th dynasty onwards, but annealing with fire and hammering also rendered the tools more brittle. Because of the metal's softness, copper tools lost their edge quickly and had to be resharpened frequently. When cutting and drilling grit was probably used, which lodged itself in the edges of the soft copper bits and performed the abrasive action.

“At first copper and bronze tools were similar to their stone equivalents, but soon the properties of the metal, among them malleability, began to influence their design. Fishing hooks were given barbs. Knives grew longer. Sowing needles were fashioned less than 1½ mm thick. Copper tools found at Kahun: 1) Piercer or bradawl with wooden handle; 2) Barbed fishing hooks; 3) Needle; 4) Pin; 5) Netting bobbin; 6) Hatchet; 7) Knives; 8) Chisel.

See Separate Article: TOOLS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: MADE OF STONE, METAL AND METEORIC IRON africame.factsanddetails.com ; COPPER (CHALCOLITHIC) AGE (4,500 to 3,500 B.C.) factsanddetails.com; CYPRUS — ANCIENT ISLAND OF COPPER factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Copper in Ancient Egypt: Before, During and After the Pyramid Age (C. 4000 – 1600 BC) by Martin Odler (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Metallurgy” by H. Garland and C. O. Bannister (2015) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Technology and Innovation” by Ian Shaw (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Proceedings of the First Intl. Conf. On Ancient Egypt Mining and Metallurgy”

by Supreme Council of Antiquities (2005) Amazon.com;

“Gold and Gold Mining in Ancient Egypt and Nubia: Geoarchaeology of the Ancient Gold Mining Sites in the Egyptian and Sudanese Eastern Deserts” by Rosemarie Klemm and Dietrich Klemm (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Bronze Age: A History from Beginning to End” by Hourly History (2024) Amazon.com;

“Tin in Antiquity: Its Mining and Trade Throughout the Ancient World with Particular Reference to Cornwall” by R.D. Penhallurick (2008) Amazon.com;

“Anatolia and the Bronze Age: The History of the Earliest Kingdoms and Cities that Dominated the Region” by Charles River Editors (2023) Amazon.com;

Copper — A Very Valuable Material in Ancient Egypt

Marks made by a copper saw are visible in a piece of basalt paving found near Khufu’s pyramid on the Giza Plateau. Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Although nowhere to be seen in the finished product, massive amounts of copper were essential to building the monument. Copper picks were used to quarry the stone. Copper saws were used to cut it, and experiments have shown that an inch of metal was lost from blades for every one to four inches of stone cut. While preparing the stone blocks for use in the pyramid, workers smoothed their surfaces with copper chisels the width of an index finger. The immense quantity of copper consumed by the construction project — not to mention the other pyramids and monumental buildings that preceded and followed it — led to an urgent search for sources of the metal. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022]

Some copper was extracted from the Eastern Desert, between the Nile Valley and the Red Sea, but the major copper mines were across the sea in the southern portion of the Sinai Peninsula. The most efficient way to access these mines was by boat. Until just over a decade ago, the earliest known Red Sea harbor was at Ayn Sukhna, which was excavated starting in 2001 by a team led by Egyptologist Pierre Tallet of the University of Paris-Sorbonne. The harbor at Ayn Sukhna appears to have been used intermittently for more than a millennium to access the Sinai, starting during the reign of Khafre (r. ca. 2597–2573 B.C.), Khufu’s son. Then, in 2008, Tallet’s team relocated a previously known but little understood coastal site at Wadi el-Jarf, some 60 miles south of Ayn Sukhna, and found that it had served as a harbor for around 50 to 70 years in the 4th Dynasty (ca. 2675–2545 B.C.), including the reign of Khufu. It is the earliest known harbor in the world.

In ongoing excavations that began in 2011, a joint expedition from the University of Paris-Sorbonne, the French Institute of Archaeology in Cairo, and Assiut University has discovered that the harbor at Wadi el-Jarf was a sprawling enterprise where hundreds of workers supported mining operations in the Sinai. The team has uncovered evidence of how these laborers were organized into groups to ensure that the site functioned smoothly. And, in a wholly unexpected and unprecedented find, they have unearthed a cache of inscribed papyri containing records of the day-to-day activities of one such group of workers — the boatmen overseen by Inspector Merer. In addition to transporting stone blocks used to build the Great Pyramid complex on the Giza Plateau, these men took part in operations elsewhere in the country, including helping to run the harbor at Wadi el-Jarf.

Ancient Egyptian Copper Mines in the Sinai

Copper mines in Ancient Egyptian territory lay in the mountains on the west side of the Sinai peninsula, chiefly indeed in the Wadi Nasb, the Wadi Maghara, and in the mountain Sarbut elchadim; with the exception of the first, where copper ore is still obtained from one shaft, they were all worked out in old times. The shafts by which they were worked are bored horizontally into the mountain, and are in the form of corridors, the roof being supported by pillars. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The most important of these mines were those of the Wadi Maghara, which were begun by King Snefru and called after him the “mines of Snefru. " On a hill in the midst of distant Thales there still stand the stone huts of the workmen as well as a small castle, built to protect the Egyptians stationed there from the attacks of the Sinai Bedouin. For though these mountain peoples may have been just as insignificant as they are now, yet they might be dangerous to the miners cut off from all intercourse with their home. King Snefru and his successors, therefore, carried on a petty warfare with these nomads, which is perpetuated in triumphal reliefs on the rocks of Thales, as the “annihilation of the mountain folk." On the other hand these mountains were exempt from the other danger which generally threatened the ancient miners of the desert; there was a well not far from these mines, and the cisterns on the fortress were filled sufficiently with the rain which fell here every year. There was provision made also for the religious needs of the workmen and soldiers; amongst other divinities revered here was a “Hathor, the lady of the malachite country," she was considered the patron saint of all the mines of Sinai. Though we cannot now find a temple to this goddess in the Wadi Maghara, yet divine worship seems to have been carried on here with all due ceremony, for Ra'enuser, a king of the 5th dynasty (if I understand the representation rightly), gave to one of the gods there a great vase to be used for his libations.

The mines of the Wadi Maghara were actively worked all through the period of the Old Kingdom, and from the time of Snefru to that of Pepi II. the kings sent their officials thither with a "royal commission. " These delegates were some of them treasury officials, and some ship captains (two offices which, During the Old Kingdom, had duties in common, for instance, both had to fetch the same precious things for the treasury); some were also officers of the army with their troops. After a long suspension of the work, the later rulers of the 12th dynasty, especially Amenemhat III., seem to have taken it up again energetically. Thus, e. g., in the second year of his reign the latter sent one of his treasurers ,Chentkhetyhotep, the treasurer of the god, the great superintendent of the cabinet of the house of silver," with 734 soldiers to the Wadi Maghara to pursue mining operations there. During the New Kingdom also, many of the Pharaohs carried on the work of these mines, the last of these kings who we know did so being Ramses III; he relates that he sent his prince-vassals thither, to present offerings to the Hathor, and to fetch many bags of malachite.

The mines called Serabit el-Khadim (Servant Mountain) were worked as early as the time of King Snefru, for he is represented there in a relief standing between two gods. " A certain Amenemhat also relates to us later that he, the “treasurer of the god, the superintendent of the cabinet, the leader of the young men, and the friend of the Pharaoh," rendered such great services there as “had not been known since the time of King Snefru. " The work was, however, first taken up in earnest by the kings of the 12th dynasty, under whom Sarbut elchadim seems to have become the center of the whole mining district. Amenemhat III. built a small temple here to the Hathor; it stood on a high rocky terrace which dominates the valley in an imposing manner. This temple was afterwards enlarged by the kings of the New Kingdom, especially by Thutmose III. Round about this sanctuary were erected numberless stelae, on which the names of many of the distinguished directors of the mines there have been passed down to posterity. These mines, like those of the Wadi Maghara, seem to have been exhausted During the New Kingdom, for none of the inscriptions there are later than the 20th dynasty. '' Finally, there were also great “copper mines “in the mountain 'At'eka, which could be reached both by sea and land; Ramses III. carried on mining operations here with great success. ''

Wadi el-Jarf — Ancient Egypt’s Copper Port

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: For Tallet, the first clue that Wadi el-Jarf had been a port was the presence of storage galleries carved into limestone foothills some three miles from the coastline. He had found similar galleries at Ayn Sukhna, which were used to safeguard boats and other materials when the port was not in use. As the team began investigating Wadi el-Jarf, additional evidence quickly emerged. A natural opening in the reefs offshore would have allowed for easy passage of boats, while an L-shaped jetty, each leg of which measures around 200 meters (650 feet) long, created a five-hectare (12-acre) zone of calm water directly in front of this opening. Near the shore, the archaeologists excavated a pair of structures that appear to have been used for lodging, food production, and processing goods. Between the structures, they found more than 100 stone anchors, some with ropes still attached. Around a mile and a half inland they unearthed a building divided into 13 parallel rooms that measures some 60 meters (200 feet) by 40 meters (130 feet), making it the largest known ancient building on the Red Sea coast. Researchers believe it likely housed around 500 workers. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022]

More than 100 stone anchors, some with ropes still attached, were found between a pair of structures near the shore at Wadi el-Jarf. When the team first arrived at the site, they found that the entrances to the 31 storage galleries had been sealed with large limestone blocks. Inside almost all the galleries they have explored, which range in length from 50 to 100 feet, the archaeologists have uncovered large quantities of cedar, pine, and rope fragments, indicating that, as at Ayn Sukhna, the galleries were used to store boats during those parts of the year when dangerous weather conditions made the Red Sea unnavigable.

Many of the galleries were also filled with ceramic storage jars, which have been key to helping Tallet’s team understand how the port worked. Given that the closest source of fresh water is a spring around six miles inland from the galleries, the researchers believe the eight-gallon jars were used to store water for harbor workers, as well as to transport goods to and from the Sinai. A number of broken jars have been found in the water near the shore. Still more have been discovered at a fortress known as el-Markha some 30 miles across the Red Sea from Wadi el-Jarf, evidence that it was the destination for expeditions from the harbor and likely served as a base for Sinai mining operations.

Copper Mines Near Wadi el-Jarf

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Pinpointing which Sinai copper mining and processing sites were being used in Khufu’s time can be difficult, but a complex of furnaces discovered in 2009 by Tallet at Seh Nasb, 10 miles north of el-Markha, gives a sense of the enterprise’s gargantuan scale. The furnaces — at least 3,000 in total — were used in an early stage of processing copper ore and were arranged in large batteries that spread out over more than half a mile. “The size of the installation makes me think this was probably from the Fourth Dynasty, when the Egyptians had a very dramatic need for copper,” says Tallet. “It’s absolutely huge. ” [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022]

The harbor at Wadi el-Jarf must have been a hive of carefully coordinated activity. Boats would have been carried around 100 miles across the desert from the Nile Valley in parts and assembled at the site. Mine workers, along with others delivering food and supplies such as wood to fuel the copperprocessing furnaces, would also have made the trek. Trains of donkeys would have constantly filed back and forth from the harbor to fetch water from the inland spring. And boats would have shuttled to and fro across the Red Sea, sending workers and supplies and returning with copper. Overlooking the site was a pair of hilltop camps situated above the storage galleries. These camps have yet to be excavated, but the researchers believe they were a control point where overseers monitored the harbor and could observe anyone approaching on desert trails. “Managing the site was an incredible logistical operation,” says Gregory Marouard, an archaeologist at Yale University who is part of Tallet’s team. “It took at least seven days to cross the desert from the Nile Valley, and they had to bring everything with them. There were also probably several different groups of workers involved, doing different jobs. And it was a seasonal operation, so when they organized a new expedition, people had to come to reopen the galleries, rebuild the boats, and so on. ”

Copper from Cyprus

Ancient Egypt also obtained copper from Cyprus. Colette and Seán Hemingway of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Cypriots first worked copper in the fourth millennium B.C., fashioning tools from native deposits of pure copper, which at that time could still be found in places on the surface of the earth. The discovery of rich copper-bearing ores on the north slope of the Troodos Mountains led to the mining of Cyprus' rich mineral resources in the Bronze Age at sites such as Ambelikou-Aletri. Tin, which is mixed together with copper to make bronze, typically at a ratio of 1:10, had to be imported. [Source: Colette Hemingway and Seán Hemingway, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“True tin bronzes appear to have been made on Cyprus as early as the beginning of the second millennium B.C. In the nineteenth century B.C., the island is mentioned for the first time in Near Eastern records as a copper-producing country, under the name "Alasia," and it continued to be an important source of copper for the Near East and Egypt throughout most of the second millennium B.C. Scholars, however, are in disagreement as to the exact meaning of "Alasia": whether it refers to a specific site on Cyprus, such Enkomi or Alassa, or to the island itself, or, less probably, to another geographic location. \^/

“Cypriot copper and bronze working was relatively modest in the Early and Middle Bronze Ages, and metalsmiths manufactured a limited range of types, including tools, weapons, and personal objects such as pins and razors. Excavations have revealed increasing metallurgical activity at settlement sites in the Late Bronze Age. Nearly all of the major centers, including Enkomi, Kition, Hala Sultan Tekke, Palaeopaphos, and Maroni, provide evidence of copper smelting, as do smaller settlements, including Alassa and Kalavasos-Ayios Dhimitrios. \^/

See Separate Article: CYPRUS — ANCIENT ISLAND OF COPPER europe.factsanddetails.com

Egyptian metal workers

King Solomon’s Mine Exploited by the Ancient Egyptians?

In 1969, an Egyptian temple dedicated to the goddess Hathor was discovered in Timna Valley in present-day Jordan Archaeologists at the time took this as evidence that mining in the area was controlled by Egypt’s New Kingdom during the Bronze Age, a few centuries earlier than the supposed reign of King Solomon.

Megan Gannon wrote in Live Science: a team lead by Erez Ben-Yosef, an archaeologist from Tel Aviv University, revisited the site, they took carbon dates at Slaves’ Hill, and found that most artifacts date to the 10th century B.C., when the Bible says King Solomon ruled. Still, there is no evidence linking Solomon or his kingdom to the mines (and little evidence outside of the Bible for Solomon as a historical figure). One theory is that the mines were controlled by the Edomites, a semi-nomadic tribal confederacy that battled constantly with Israel. |~| [Source: Megan Gannon, Live Science, November 25, 2014 |~|]

In 1969, Beno Rothenberg and his crew began to excavate near a towering rock formation known as Solomon’s Pillars — ironic, because the structure they uncovered ended up destroying the site’s ostensible connection to the biblical king. Here they found an Egyptian temple, complete with hieroglyphic inscriptions, a text from the Book of the Dead, cat figurines and a carved face of Hathor, the Egyptian goddess, with dark-rimmed eyes and a mysterious half-smile. Not only did the temple have nothing to do with King Solomon or Israelites, it predated Solomon’s kingdom by centuries — assuming such a kingdom ever existed. “There is no factual and, as a matter of fact, no ancient written literary evidence of the existence of ‘King Solomon’s Mines,’” Rothenberg wrote

See Separate Article: KING SOLOMON'S MINES: PULP FICTION AND ARCHAEOLOGY africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024