MINING IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Flint, stone, copper, feldspar, amesyth, jasper, agate, turquoise, Egyptian alabaster, and malachite were mined and quarried from sites mostly in Eastern Desert, the Sinai and around the Red Sea. Nubia was a major source of gold and exotic materials. Valuable obsidian came from Ethiopia. Egyptians may have used amber in mummification because its is a powerful desiccant (or drying agent).

Elizabeth Bloxam of University College London wrote: “Research into the technologies used to extract semi-precious stone from mines is still an underdeveloped field of study in Egyptology, despite the large-scale use of these materials in antiquity. Ancient quarry and mining sites are the “forgotten” archaeological sites, even though they can comprise material culture such as roads, settlements, epigraphic data, and often spectacular partly finished monumental objects. Moreover, ancient production sites can enhance our understanding of the lives of the non-elite in antiquity, in particular the social organizations of raw material procurement, an aspect that still remains poorly understood. As some of the most endangered archaeological sites in Egypt, ancient production sites are under enormous threat from modern quarrying, urban development, and other mega-projects. Source:Elizabeth Bloxam, University College London, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Ancient mining sites often present extensive cultural landscapes comprising a range of material culture; however, their research potential is still not fully recognized. Current research is re- shaping ideas about these poorly understood activities, for instance, the major use of stone tools and fire in extracting hard stones, transmission of stone-working technologies across often deep time depths, and the role of skilled kin-groups as a social construct rather than large unskilled labor forces. Although questions of chronology of extraction techniques, methods, and development of theoretical approaches to interpretation are still in their early stages, with a continued emphasis on archaeological and geological survey of these sites, the potential exists to further address some of these important questions.”

Gemstones such as amazonite, amethyst, jasper, garnet, turquoise, peridot, emerald, and carnelian were all mined in Egypt during antiquity, largely for jewelry. The main geographical locations of some of the most important gemstone mines are in the Eastern Desert, such as Wadi Sikait (emerald), the Gebels Migif and Hafafit (amazonit), and Wadi el-Hudi (amethyst). Stele Ridge in Lower Nubia in the environs of Gebel el-Asr (“Chephren’s Quarry”) is the only known source of carnelian, and the Sinai has concentrations of turquoise and copper mines, the most well known being at Serabit el-Khadim. All these sources were exploited in antiquity, although the explosion in gemstone mining is most associated with the Middle Kingdom.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

QUARRYING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

METALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: BRONZE, COPPER, METEORIC IRON africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PRECIOUS METALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: GOLD, SILVER, MINING, SOURCES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

GEM STONES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Egyptian Technology and Innovation” by Ian Shaw (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Copper in Ancient Egypt: Before, During and After the Pyramid Age (C. 4000 – 1600 BC) by Martin Odler (2023) Amazon.com;

“Proceedings of the First Intl. Conf. On Ancient Egypt Mining and Metallurgy”

by Supreme Council of Antiquities (2005) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Metallurgy” by H. Garland and C. O. Bannister (2015) Amazon.com;

“Jewels of Ancient Nubia” by Yvonne Markowitz, Denise Doxey (2014) Amazon.com;

“Hidden Treasures of Ancient Egypt: Unearthing the Masterpieces of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo” by Zahi Hawass (National Geographic, 2004) Amazon.com;

“Gold and Gold Mining in Ancient Egypt and Nubia: Geoarchaeology of the Ancient Gold Mining Sites in the Egyptian and Sudanese Eastern Deserts” by Rosemarie Klemm and Dietrich Klemm (2012) Amazon.com;

“Nubian Gold: Ancient Jewelry from Sudan and Egypt” by Peter Lacovara and Yvonne J. Markowitz (2019) Amazon.com

“The Bronze Age: A History from Beginning to End” by Hourly History (2024) Amazon.com;

“Tin in Antiquity: Its Mining and Trade Throughout the Ancient World with Particular Reference to Cornwall” by R.D. Penhallurick (2008) Amazon.com;

“Anatolia and the Bronze Age: The History of the Earliest Kingdoms and Cities that Dominated the Region” by Charles River Editors (2023) Amazon.com;

“Gold, Frankincense, Myrrh, And Spiritual Gifts Of The Magi” by Winston James Head Amazon.com ;

Mining Gemstones in Ancient Egypt

James Harrell of the University of Toledo wrote: “The extraction technologies employed at ancient Egyptian gemstone mines are essentially the same as those at the ornamental stone quarries, but the small crystal masses and thin veins where gemstones are typically found resulted in generally smaller workings. Both hand-held and hafted stone tools known as pounders or mauls were used to hack out pieces of gem-bearing bedrock. Although copper and, later, bronze picks and chisels were available during the Dynastic Period, they were too soft to work the hard igneous and metamorphic rocks in which most gemstones occur, and for these the stone tools were superior. Stone tools were largely replaced by “iron” ones (actually low-grade steel) toward the end of the Late Period. Mine excavations were usually surface pits and trenches, but those for emerald and turquoise also involved underground excavations like those found in the ancient gold workings.[Source: James Harrell, University of Toledo, OH, Environmental Sciences, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“The raw gemstones, always occurring in relatively small pieces, would have been carried from the mines on the backs of men or pack animals (probably donkeys). They were brought to workshops where they were laboriously fashioned into their many forms, with beads being the most common. During the Dynastic Period, the Egyptians had no abrasive material harder than the hardest gemstones they worked, which were the many quartz varieties with a Mohs hardness of 7. It is often claimed that the Egyptians used emery (a granular combination of corundum and iron oxide, Mohs = 8-9) as an abrasive, but there is no credible archaeological evidence for this. What the Egyptians surely did use, and which they had in great abundance, was silica (SiO2) in its many forms, most notably: massive microcrystalline quartz (chert or flint), massive macrocrystalline quartz (silicified sandstone or quartzite), and loose macrocrystalline quartz (sand). Any material can be cut, ground, and polished by the material itself—the process simply takes longer than when a harder abrasive is used. Silica was thus a sufficiently effective abrasive for the Dynastic gemstones. During the late Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, diamond (Mohs = 10) and corundum (Mohs = 9) were almost certainly imported into Egypt from India and used as abrasives, especially for the harder gemstones like emerald (Mohs = 7.5-8) and sapphire (blue corundum). Emery from Mediterranean or Eastern sources may also have been employed as an abrasive at this time.”

Elizabeth Bloxam of University College London wrote: “Gemstone mines in Egypt, similar to quarries, are under pressure from modern mining. Due to almost continuous mining of some key resources, their preservation, in terms of identifying the earliest phases of mining, is largely poor. Moreover, given the large quantities of epigraphic data found in mining contexts, such as standing stelae, votive objects, and a temple to Hathor at Serabit el- Khadim, past research has largely focused on documenting these aspects of the material culture, rather than the mines themselves. Although our knowledge of gemstone extraction techniques in the Pharaonic period is limited, the main corpus of objects remaining in such sites are stone tools, which once again suggests the important role they played in separating gemstones from ore bearing rocks. [Source: Elizabeth Bloxam, University College London, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The carnelian mines at Stele Ridge in the environs of Gebel el-Asr (“Chephren’s Quarry”) in Lower Nubia present one of the few well preserved Pharaonic gemstone mining sites, largely of the Middle Kingdom. The mines are extremely hard to visualize due to them being sub-surface extractions characterized on the surface as circular, oval, and longitudinal subterranean trenches surrounded by spoil heaps. These shallow subterranean extractions, often only a meter in depth, were extensively exploited to access the stone that occurs in cracks between granite outcrops. Stone tools seem to have been the main implements used to separate the gemstone from the ore, given the absence of marks made by metal. Pounders found inside an excavated mine and in surrounding areas suggest that the method of mining was by pounding of the granite to release the gemstone.

“Stone tool assemblages made up of flint scrapers, hand axes, and pounders comprise the largest corpus of mining tools found at the Serabit el-Khadim turquoise and copper mines. Yet it is interesting to note, given that these mines were intensively exploited between the Middle and New Kingdom, that these assemblages show little variation from those found in earlier nearby Chalcolithic sites, implying no demonstrable transformation between Early Dynastic Period and Middle Kingdom mining techniques. Despite the problems in assessing transformations in mining technologies, it is suggested that the Middle Kingdom mines are more represented by horizontal tunneling and mines in the New Kingdom by the creation of large galleries with deep hollows made in the surfaces.”

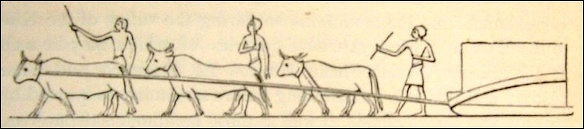

transporting stone blocks

Social Context of Mining in Ancient Egypt

Elizabeth Bloxam of University College London wrote: “Assessing the social context of quarry and mining expeditions in the Pharaonic period in terms of numbers involved and hierarchies has been difficult to determine, given that associated settlement evidence is scant. Even in quarries outside of the Nile valley, such as Gebel el-Asr (“Chephren’s Quarry”), Widan el-Faras, and Umm el-Sawan, only small ephemeral camps characterized by low-level dry-stone walls and the use of natural rock overhangs have provided any evidence of habitation. Ceramics are also minimal in these and other quarry sites; hence, estimating the numbers of people involved in these activities is problematic and why there has been a reliance on textual sources. However, even taking into account poor preservation, recent findings cannot attest to quarry labor forces being over a maximum of 200 individuals, thus largely contradicting the Wadi Hammamat quarry inscriptions, which list expeditions into the tens of thousands. [Source: Elizabeth Bloxam, University College London, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“In terms of provisioning of the labor force in quarries remote from permanent settlements and crucial access to water, evidence from excavation of two small camps and several wells at Gebel el-Asr (“Chephren’s Quarry”) in the Western Desert has given us some decisive insights. Constituting dwellings for no more than 25 people, one-third of each camp was devoted to food production, in particular bread making. In addition to consumption of local fish, birds, and mammals, access to water was relatively easy from shallow wells only up to one meter in depth. The shallowness of the wells has provided important insights into the climatic conditions that prevailed during the Old Kingdom exploitation, indicating seasonally wetter periods far removed from what we see today.

“Grappling with the archaeological problems of fragmentary data, particularly in terms of understanding the social organization of resource exploitation in the Pharaonic era, it has been important to reassess our ideas about the make up of quarry and mining labor forces from concepts in other areas of the social sciences. In particular cross-cultural comparison, anthropology, social archaeology, and landscape archaeology have provided useful models through which production data can be reinterpreted. Developing such methodologies is important if we are to understand the social context behind these activities, away from largely unreliable explanations via just a few written sources. Recent research is now widening the gap between the textual version of practice vis-à-vis the archaeological record.

“It has recently been argued that small groups of specialists, rather than large detachments of unskilled workers, made up quarrying and mining labor forces. These groups, loosely structured around kinship ties, might explain the general observation of undeniably skilled practice and transmission of specific extraction technologies over many generations.”

Diodorus’s Description of Gold Mining in Egypt

Carol Meyer of the University of Chicago wrote:Diodorus is frequently cited as the only ancient account of Egyptian gold mining. He states he tried to check his sources, but he relied on Agatharcides' account from the 2nd century B.C. It is not clear whether either writer ever saw a gold mine; however, Diodorus wrote approximately half a millennium before the Byzantine/Coptic operations at Bir Umm Fawakhir. If nothing else, the political and economic situation had changed. Diodorus' kings and queens of Egypt (the last of whom was Cleopatra) had long been replaced by distant emperors in Rome or Constantinople, and Egypt had been reduced to a province. [Source: Carol Meyer, Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, “Bir Umm Fawakhir: Insights into Ancient Egyptian Mining JOM 9:3 (1997), 64-68, JOM |]

golden cylinder seal of the Pharaoh of Djedkare Isesi

Diodorus wrote: "At the extremity of Egypt and in the contiguous territory of both Arabia and Ethiopia there lies a region which contains many large gold mines, where the gold is secured in great quantities with much suffering and at great expense. For the earth is naturally black and contains seams and veins of a marble which is unusually white and in brilliancy surpasses every- thing else which shines brightly by its nature, and here the overseers of the labour in the mines recover the gold with the aid of a multitude of workers. For the kings of Egypt gather together and condemn to the mining of the gold such as have been found guilty of some crime and captives of war, as well as those who have been accused unjustly and thrown into prison because of their anger, and not only such persons but occasionally all their relatives as well, by this means not only inflicting punishment upon those found guilty but also securing at the same time great revenues from their labours. And those who have been condemned in this way—and they are a great multitude and are all bound in chains—work at their task unceasingly both by day and throughout the entire night, enjoying no respite and being carefully cut off from any means of escape; since guards of foreign soldiers who speak a language different from theirs stand watch over them, so that not a man, either by conversation or by some contact of a friendly nature, is able to corrupt one of his keepers. [Source: Ancient Egyptian Gold Refining: A Reproduction of Early Techniques, J. H. F. Notton, Johnson Matthey & Co Limited, London, 1974]

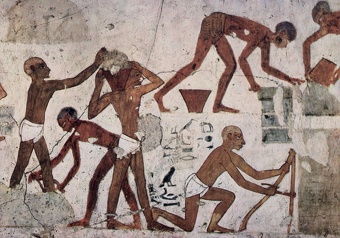

“The gold bearing earth which is hardest they first burn with a hot fire, and when they have crumbled it in this way they continue the working of it by hand;and the soft rock which can yield to moderate effort is crushed with a sledge by myriads of unfortunate wretches. And the entire operations are in charge of a skilled worker who distinguishes the stone and points it out to the labourers; and of those who are assigned to this unfortunate task the physically strongest break the quartz-rock with iron hammers, applying no skill to the task, but only force, and cutting tunnels through the stone, not in a straight line but wherever the seam of gleaming rock may lead. Now these men, working in darkness as they do because of the bending and winding of the passages, carry lamps bound on their foreheads; and since much of the time they change the position of their bodies to follow the particular character of the stone they throw the blocks, as they cut them out, on the ground; and at this task they labour without ceasing beneath the sternness and blows of an overseer.

"The boys there who have not yet come to maturity, entering through the tunnels into the galleries formed by the removal of the rock, laboriously gather up the rock as it is cast down piece by piece and carry it out into the open to the place outside the entrance. Then those who are above thirty years of age take this quarried stone from them and with iron pestles pound a specified amount of it in stone mortars, until they have worked it down to the size of a vetch. Thereupon the women and older men receive from them the rock of this size and cast it into mills of which a number stand there in a row, and taking their places in groups of two or three at the spoke or handle of each mill they grind it until they have worked down the amount given them until it has the consistency of the finest flour.

"In the last steps the skilled workmen receive the stone which has been ground to powder and take it off for its complete and final working; for they rub the marble which has been worked down upon a broad board which is slightly inclined, pouring water over it all the while; whereupon the earthy matter in it, melted away by the action of the water, runs down the in- clined board, while that which contains the gold remains on the wood because of its weight. And repeating this a number of times, they first of all rub it gently with their hands, and then lightly pressing it with sponges of loose texture they remove in this way whatever is porous and earthy, until there remains only the pure gold-dust.

"Then at last other skilled workmen take away what has been recovered and put it by fixed measure and weight into earthen jars, mixing with it a lump of lead proportionate to the mass, lumps of salt and a little tin, and adding thereto barley bran; thereupon they put on it a close- fitting lid, and smearing it over carefully with mud they bake it in a kiln for five successive days and as many nights; and at the end of this period, when they have let the jars cool off, of the other matter they find no remains in the jars, but the gold they recover in pure form, there being but little waste. This working of the gold, as it is carried on at the farthermost borders of Egypt, is effected through all the extensive labours here described; for Nature herself, in my opinion, makes it clear that whereas the production of gold is laborious, the guarding of it is difficult, the zest for it is very great, and that its use is halfway between pleasure and pain.”

Mine Officials in Ancient Egypt

The officials who, under the Old and the Middle Kingdom, directed the works at Hammamat mines and quaries , were (as in the mines) mostly treasurers and ship captains; but at the same time there were in addition royal architects and artists, who also came hither to fetch this precious stone for the coffin or the statue of the Pharaoh. The higher officials — for there were men of the highest rank amongst them, “nearest friends of the king, hereditary princes and chief prophets," and even a “great royal son “— came here probably only as inspectors, whilst the real direction of the quarrying work was placed in the hands of persons of somewhat lower standing. Thus, under the ancient King Pepi, the treasurer 'Ech'e was evidently the actual director of the quarries, and as such he once appears independently. The inscriptions however only mention him as a subordinate, while they give the place of honour to Ptah-mer-'anch-Meryre', “the superintendent of all the works of the king, the nearest friend of the king, and the chief architect in the two departments. " This great man twice paid a visit of inspection to Hammamat, once accompanied by his son, and once, when it was a question of the decoration of a temple, with a "superintendent of the commissions of the sacrificial estates of the two departments. " Moreover, the treasurer 'Ech'e himself also had subordinates, to whom he could occasionally delegate his office; there were five “deputy artists," and one or two architects, who were as a rule subordinate to him, but who are also mentioned in one place as acting independently. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The most ancient “royal mission “mentioned in the Hammamat inscriptions took place under King 'Ess'e of the 5th dynasty. '' In the confusion which ensued after the 6th dynasty, the works seem to have been in abeyance. Under the rule of a King Mentuhotep of the 11th dynasty a new epoch commenced. A miracle took place: “A well was discovered in the midst of the mountains, 10 cubits broad on every side, and full of water up to the brink. " It was situate, if I rightly understand, “out of reach of the gazelles, and hidden from the barbarians. The soldiers of old times and the early kings had passed in and out close by it, but no eye had seen it, no human face had glanced upon it," until through the favor of the god Min, the protector of desert paths, it was granted to King Mentuhotep (or rather to his people) to find it, and thus “to make this country into a sea. " “This discovery was made in the second year of the king's reign, when he had sent his highest official the governor to Hammamat, to direct the quarrying of “the splendid great pure stone which is in that mountain "; that the coffin with the name of “eternal remembrance “might be prepared for the tomb of the monarch as well as monuments for the temples of Upper Egypt.

“Thither resorted Amenemhat, the hereditary prince, the chief of the town, the governor and high judge, the favorite of the king, the superintendent of works — who is great in his office and powerful in his dignity — who occupies the first place in the palace of his lord — who judges mankind and hears their evidence — he to whom the great men come, bowing themselves, and before whom all in the whole country throw themselves on the earth — who is great with the king of Upper Egypt and powerful with him of Lower Egypt, with the white crown and the red crown . . — who judges there without partiality — the chief of all the south country — who makes a report upon all that exists and that does not exist — commander of the lord of the two countries, and of understanding heart of the commission of the king . . . he resorted to this honourable country, accompanied by the choicest soldiers, and the people of the whole country, the mountain folk, the artists, the stone-hewers, the metalworkers, the engravers of writing, . . . the gold-workers, the treasury officials — in short, by all the officials of the Pharaonic treasury and by all the servants of the royal household. " He carried out his commission successfully, and more especially he obtained a sarcophagus 8 cubits long, 4 cubits broad, and 2 cubits high. Calves and gazelles were sacrificed as thank-offerings to Min of Coptos, the protector of this desert, incense was offered up to him, and 3000 men then dragged the great block into Egypt. “Never had such a block been transported into that country since the time of the god. The soldiers also suffered no loss, not a man perished, not one donkey's back was broken, not one artisan was killed. "

Bir Umm Fawakhir Site: an Ancient Egyptian Gold-Mining Site

Bir Umm Fawakhir

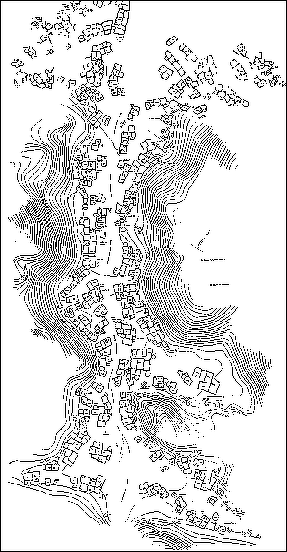

Carol Meyer of the University of Chicago wrote: “Archaeological surveys at the site of Bir Umm Fawakhir in the central Eastern Desert of Egypt have clarified its role as a 5th-6th century gold-mining town. To date, 152 out of an estimated 216 buildings in the main settlement have been mapped in detail, eight outlying clusters of ruins have been identified, and four ancient mines have been inspected. In conjunction with Diodorus Siculus' first century B.C. account of Egyptian gold mining, the recent archaeological discoveries permit new insights into ancient Egyptian mining towns and techniques. Some evidence of activity at Bir Umm Fawakhir in earlier Roman, Ptolemaic, and pharaonic times has also been found.[Source: Carol Meyer, Oriental Institute, University of Chicago,“Bir Umm Fawakhir: Insights into Ancient Egyptian Mining JOM 9:3 (1997), 64-68, JOM |]

“Although many sources of gold have been suggested in the Byzantine era when Bir Umm Fawakhir was at its peak (confiscation from pagan temples; deposits in Turkey; or imports from East Africa, the Sudan, sub-Saharan Africa, or the Caucasus), Egypt has never been mentioned. This is a little surprising as Egypt was famous throughout antiquity as a gold source. |

“The Bir Umm Fawakhir site, surveyed by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago in 1992, 1993, and 1996, is the first entire ancient Egyptian gold-mining community to be studied archaeologically. Located in the central Eastern Desert of Egypt, Bir Umm Fawakhir was long believed to be a Roman caravan station serving traffic traveling from the Nile to Red Sea but was actually a 5th-6th century Byzantine/Coptic gold-mining town. The sprawling settlement is estimated to have housed slightly more than 1,000 people who worked the mines riddling the mountainsides and reduced and washed the ore. Although direct textual evidence is lacking, it seems probable that in light of the compelling need for gold, the imperial governors of the Thebaid (Upper Egypt) and their bureaucracies were concerned with the mines at Bir Umm Fawakhir, their product, and their support. Also, it is difficult to see who, apart from the government, could have recruited and routinely supplied so many workers in so remote a region. |

“The site can offer a great deal of information about ancient mining. First, it is an opportunity to study an entire mining community without excavation. Second, it is a remarkably complete community, even without such features as central administrative buildings or churches. Not only houses and outbuildings survive, but also streets, paths, roads, cemeteries, wells, guardposts, and mines and quarries. It is the first time an ancient Egyptian gold-mining site has been archaeologically studied.” |

Bir Umm Fawakhir Site

Bir Umm Fawakhir location

Carol Meyer of the University of Chicago wrote: “Bir Umm Fawakhir lies in the rugged Precambrian mountains of the central Eastern Desert and is almost exactly halfway between the Nile and the Red Sea. The site is approximately 65 kilometers (two and a half to three days by camel) from Quft (ancient Coptos). This route, which is the shortest from the Nile to the Red Sea, has been in use for at least 5,000 years and follows a series of wadis (dry canyons) cutting through the mountains. The most famous ancient site enroute is the Wadi Hammamat, which was the source of a fine-grained dark graywacke that was highly prized in pharaonic times for statues, sarcophagi, and the like. [Source: Carol Meyer, Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, “Bir Umm Fawakhir: Insights into Ancient Egyptian Mining JOM 9:3 (1997), 64-68, JOM |]

“Bir Umm Fawakhir, about 5 kilometers northeast, lies in a different geological zone. The Fawakhir granite is a stock intruded into the older Precambrian rocks. As no agriculture has ever succeeded in this hyperarid desert, the only resources are mineral, namely, gold, granite, and water. The granite was quarried to no great extent in the Roman period, but it also acts as an aquifer, carrying water in tiny cracks until it is stopped by the dense ultramafic rocks to the west.3 Wells have always been dug there. Most importantly, however, the quartz veins injected into the granite are auriferous, particularly towards the edge of the stock. (Many other minerals occur as well, including pyrite, chalcopyrite, and hematite, which stains the quartz reddish.) |

“Estimates of the gold yield vary widely.4,5 What is consistent among these analyses, however, is the conclusion that the yield at Bir Umm Fawakhir is very low compared to the older mines about 4 kilometers southeast in the Wadi el-Sid. The latter were probably worked out well before the Coptic/Byzantine period. The combination of the paucity of rich ore sources as well as the urgent need for gold in the 5th and 6th centuries probably explains why the low-yield mines at Bir Umm Fawakhir were worked and why virtually nothing has happened at the site since.” |

Bir Umm Fawakhir Settlement

Carol Meyer of the University of Chicago wrote: “The main settlement at Bir Umm Fawakhir is not visible from the road, but after turning the spur of a hill, a visitor can walk the length of the Coptic/Byzantine town for about half a kilometer . The ruins lie in a long, narrow wadi, the steep sides of which enclose the town like a wall, while the sandy bottom serves as the main street.[Source: Carol Meyer, Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, “Bir Umm Fawakhir: Insights into Ancient Egyptian Mining JOM 9:3 (1997), 64-68, JOM |]

Bir Umm Fawakhir Settlement

“Researchers have mapped, in detail, 152 out of an estimated 216 buildings so far. Individual houses are laid out on both sides of the street, and many are still a meter or more in height. Doors, stone benches, and wall niches for storage are also preserved in many cases. The basic pattern is a two-or three-room house, but several houses are often joined into larger agglomerated units. The largest building mapped so far is Building 106, which has 22 rooms. |

At Bir Umm Fawakhir's main settlement, the plaza area is surrounded by buildings 92, 100, 101, 102, 99, 97, and part of 93. Granite Quarry 2 lies at the foot of the hill on the left. The main street runs northwest toward the modern road and settlement. The Roman watch tower is on the mountain top at the far upper right. Scattered around the houses are a number of one-room outbuildings: a smaller, rounded type and a larger, rectangular kind. Without excavation, it cannot be determined whether the outbuildings were used for kitchens, workshops, animals, storage, latrines, or something else. |

“Several cemetery areas have also been identified on the ridges around the town. The graves are simple cists built of granite slabs or natural clefts in the granite with cairns piled on top. All of the graves found so far are small and thoroughly looted, but the pottery scattered around them indicates that they are of the same period as the main settlement. |

“Apart from the sherds, which are thick on the ground and used as the primary dating evidence,2,3,6 surface finds are sparse. In particular, no written evidence has yet been recovered from the site aside from the dipinti, which are dockets painted in red on the shoulders of wine jars. Written in a cursive Greek hand and highly fragmentary, the dipinti have so far yielded little information beyond showing the presence of an imported luxury (i.e., wine) at a remote site. |

“With the potential exception of two possible community bake ovens, all of the buildings mapped so far appear to be domestic. Crosses and other Coptic symbols indicate that the population was Christian, but no church has been located. Likewise, no administrative buildings, storehouses, or workshops have been found, although there is some reason to believe they existed closer to the modern road, where the wadi wash is heaviest. |

“Particularly striking is the lack of any formal defenses, which is surprising for a gold-producing site in a desert where security was often a concern. Only a couple of guardposts have been found on high ridges overlooking the site. The more prominent guardpost lacks any formal structures beyond a few rough walls for shade or windbreaks. It is marked by ancient graffiti scratched on granite boulders and commands a view of all three roads leading to the wells, many of the mines, and much of the settlement.” |

“In addition to the detailed mapping of the main settlement, the researchers have also begun a walking survey of the immediate vicinity. Eight outlying clusters of ruins of the same date as the main settlement have been identified, and more may exist. The outlying sites range in size from a few huts to more than 60 buildings in one site (Outlier 6). Outlier 2, on the Roman road between the wells and granite quarry 1, is particularly well preserved. One house may still stand to its original height of about 2 m, and two houses have silos associated with them. The silos, built of cobbles and thick mud plaster, are of particular interest because such features have not been detected elsewhere on the site and because their association with individual houses does not suggest central control of grain rations.” |

Earliest Activity at Bir Umm Fawakhir Site

Carol Meyer of the University of Chicago wrote: “Exploitation of the Eastern Desert extends far back into prehistory, but at Bir Umm Fawakhir, good evidence goes back only to the late New Kingdom period (ca. 1307-1070 B.C.). Middle Kingdom, Old Kingdom, and Predynastic (roughly 3200-ca. 1783 B.C.) inscriptions are present in the Wadi Hammamat, but not at Bir Umm Fawakhir or in the Wadi el-Sid. [Source: Carol Meyer, Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, “Bir Umm Fawakhir: Insights into Ancient Egyptian Mining JOM 9:3 (1997), 64-68, JOM |]

Mine opening at Bir Umm Fawakhir

“Roman activity is attested, though it is less extensive than when the entire site of Bir Umm Fawakhir was considered 1st-2nd century A.D. The small granite quarries were probably Roman undertakings, although possibly only exploratory. There is a small amount of Roman pottery in Quarry 2 with quarrying marks identical to those at a known major granite quarry at Mons Claudianus. A couple of partly quarried blocks have been incorporated in 5th-6th century houses, and the Romans had an unexcelled passion for handsome and exotic stones. The Roman period ostraca (letters and messages written on potsherds) reported as coming from Bir Umm Fawakhir pertain to military activity10 and probably came from the vicinity of the modern mines in the Wadi el-Sid. |

“The modern mines, operated in the 1940s and 1950s, were probably the focus of most of the ancient efforts as well. Tailings there yielded a handful of sherds of Roman, possibly Ptolemaic (334-64 B.C.), and Late Period (26th Dynasty, 664-535 B.C.) dates. |

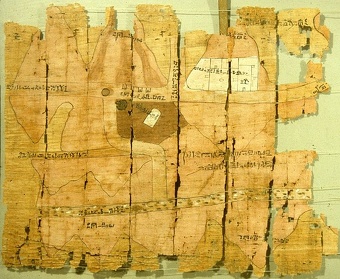

“The 1996 survey located the remains of late New Kingdom activity near the Wadi el-Sid mines. The Turin Papyrus, dateable to the reign of Ramses IV of the 20th Dynasty (ca. 1163-1156 B.C.), can reasonably be read as a map to the stone quarries in the Wadi Hammamat. The papyrus also shows a well with "a Mountain of Gold" and a "Mountain of Silver" just beyond.11 |

“Thus, while the map indicates that pharaonic mines ought to exist in the vicinity of Bir Umm Fawakhir, the survey has only recently been able to document them. Some very large (ca. 8 meters square) and heavy slabs with shallow depressions on the top, unlike the smaller and deeper Bir Umm Fawakhir grinding stones, may represent pharaonic or Ptolemaic ore reduction activities, but all stones found so far have been pushed out of any sort of context by modern road building. "In the last steps the skilled workmen receive the stone which has been ground to powder;...they rub [it] upon a broad board which is slightly inclined, pouring water over it all the while; whereupon the earthy matter in it, melted away by the action of the water, runs down the board, while that which contains the gold remains on the wood because of its weight. And repeating this a number of times, they first of all rub it gently with their hands, and then lightly pressing it with sponges of loose texture they remove...whatever is porous and earthy, until there remains only the pure gold-dust." The accounts of 19th century travelers do mention gold-washing tables at Bir Umm Fawakhir, but they have probably been destroyed by modern mining activity. It is unlikely that final refining was carried out on site. It seems more reasonable that the washed gold dust was then transported to the valley, where fuel was more abundant.” |

Mines and Mining at Bir Umm Fawakhir Site

Carol Meyer of the University of Chicago wrote: “The largest mine at Bir Umm Fawakhir inspected in 1996 runs about 100 meters horizontally into the mountain and is roughly two meters high. It has two short side galleries, an air shaft, and oblong holes pounded in the rock at the working faces. It shows no signs of fire-setting; there is neither charcoal nor ash, and none of the splintered-out niches characteristic of fire-setting. The granite is jointed, fissured, and rotten in places. This is especially true of the third and fourth mines inspected. The workings are primarily an open-cast trench running diagonally up a granite hill. In two places, however, they dive underground to follow the quartz veinlets. Here, the granite crumbles underfoot. Thus, there seems to have been no need for fire-setting; the quartz is tough, but the surrounding rock can be splintered away. [Source: Carol Meyer, Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, “Bir Umm Fawakhir: Insights into Ancient Egyptian Mining JOM 9:3 (1997), 64-68, JOM |] “The ancient miners used two techniques: open-cast trenches following the quartz veins from the surface and shafts sunk horizontally or diagonally into the mountainsides. A number of the shafts had stone walls reinforcing the entrances or platforms at the edge, presumably to aid in raising and lowering men, boys, baskets, tools, and ore. In January 1996, the researchers inspected four of the mine shafts in order to determine the mining techniques used and to check the evidence from Bir Umm Fawakhir against the 1st century B.C. account of Diodorus Siculus.

“The first stage of mining that Diodorus describes is fire-setting, which is used to shatter the rock. "The gold-bearing earth which is hardest they first burn with a hot fire, and when they have crumbled it...they continue the working of it by hand; and the soft rock which can yield to moderate effort is crushed with a sledge by myriads of unfortunate wretches. And the entire operations are in charge of a skilled worker who distinguishes the stone and points it out to the labourers;...the physically strongest break the quartz-rock with iron hammers, applying no skill to the task, but only force." |

“Diodorus also discusses how the stone is quarried. "The boys there who have not yet come to maturity, entering through the tunnels into the galleries formed by the removal of the rock, laboriously gather up the rock...piece by piece and carry it out into the open to the place outside the entrance. Then those who are above thirty years of age take this quarried stone from them and with iron pestles pound a specified amount of it in stone mortars, until they have worked it down to the size of a vetch." |

“Iron tools, or metal of any sort, have not yet been found at Bir Umm Fawakhir. However, metal and wood are so precious in the desert that they would have been the first things removed. Mortars, in the sense of deep basins for pounding, are also not common at Bir Umm Fawakhir. Those that have been recovered are limestone, which is unsuitable for crushing quartz. On the other hand, hundreds of crushing stones have been found on the site. They are made of rough blocks of basalt, granite, or porphyritic granite with smooth upper surfaces that measure about 20 centimeters x 20 centimeters square, with a depression pecked in the middle. Almost all of the crushing stones were found in secondary context or loose on the surface, but one is still in situ at the mouth of the fourth mine inspected, with fist-sized and smaller chunks of quartz scattered around it. It seems then, that the ore, mined in virtual darkness, was immediately reduced at the mouth of the mine, and the pieces worth the considerable effort of further reduction were picked out. |

“Diodorus continues with the next stage of ore working. "Thereupon the women and older men receive from them the rock of this size and cast it into mills of which a number stand there in a row, and taking their places in groups of two or three at the spoke or handle of each mill they grind it until they have worked [it] down...to the consistency of the finest flour."|

“The evidence compiled from the Bir Umm Fawakhir survey supports Diodorus' account. Both the upper and lower stones of numerous rotary querns or millstones have been found on site . Rotary mills are considered to have been a late Ptolemaic or Roman introduction; the earlier millstones were flat or concave.8,9 Not yet explained, however, are the saddle querns, which are grinding stones of granite or porphyritic granite that measure about 80 centimeters long and have a shallow dished-out depression. These were presumably worked with oblong upper handstones. It is unknown, however, whether the grinding stones were used at an intermediate stage of grinding (e.g., coarse versus fine), used for something else (e.g., wheat flour), or were earlier in date.” |

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Bir Umm Fawakhir images, Carol Meyer, Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago.

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024