RATION SYSTEM IN ANCIENT EGYPT

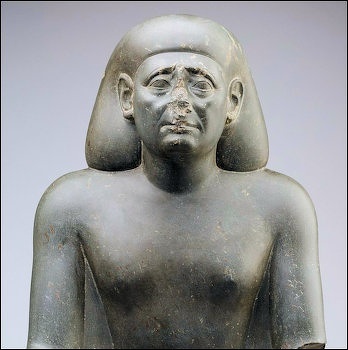

official

Hana Vymazalova, a Czech Egyptologist, wrote: “The distribution of rations can be found in documents from different period of the Egyptian history but the general features of the ration system is not easy to trace. Most of the sources are the more or less fragmentary lists of wages/payments that reflect various conditions, such as status of the recipients, period to which the payment corresponds etc, that are not always known to us. Other documents provide us with categories of allowances ascribed to the workmen and officials who participated on the same project. A few traces of a systematic approach can be recognized in the evidence, for instance value-units and day’s work units, but many details remain unclear. Bread, beer and grain represented the basic components of the rations in all periods. Bread and beer was often allocated daily while the grain was at some periods used as a monthly payment. On the other hand meat was considered an extra ration while linen and other valuable products could be distributed in longer periods, for instance once a year. Rations were distributed to the attendants of projects organized by the state but similar payments in the form of commodities occurred in exchange for a hired service in the private sphere. [Source: Hana Vymazalova, a Czech Egyptologist, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Rations (compensation in the form of food or provisions) constituted the basis of the redistribution economy of the ancient Egyptian state and are usually understood as payment given in return for work. The Egyptian evidence shows no clear difference between the rations of laborers and the wages of personnel hired to perform services for projects organized by, or connected to, the state. It has therefore been suggested that rations and wages occasionally merged. Rations were a component of royal projects of all kinds, including, for example, the construction of funerary complexes, the maintenance of the cults of deceased rulers, the perpetuation of the cults of temple deities, military expeditions, expeditions to quarries, and agricultural work. They were also employed in the private sphere as payment for those who worked, for instance, on an estate or on projects organized by non-royal individuals. Rations were applied to both the work force of laborers and to the officials who supervised them.

“The basic rations in all periods included bread and beer, often supplemented by grain (mostly barley [jt ] and wheat [ bdt] ).Additionally, meat, vegetables, cloth, oil, and other commodities were d istributed to the workers on a less frequent basis. Evidence for rations is found in administrative and economic documents from various periods, though rations also figure among the subjects of calculations presented in mathematical texts.

“The major aim of these calculations was to demonstrate methods of solving mathematical problems (for instance, arithmetical progressions), but we can also detect in them some reflections of the principles by which rations were graded. The mathematical texts attest to the practice of bureaucrats of controlling the quality of bread and beer made from a given quantity of grain/flour (psw-problems) and of comparing the value of bread and beer of differing qualities (DbAw-problems)(on the making of bread and beer). The ration or payment lists that have survived tend not to specify the quality of the bread and beer, and this indicates that some sort of standard norm existed in the system. Bread molds and beer jars, abundantly attested in the archaeological r ecord, indicate that each site and period operated with more or less standardized forms and sizes. Such standardization is today a helpful tool in archaeological context dating. “

See Separate Article: MONEY AND BARTER IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Commerce and Economy in Ancient Egypt” by Andras Hudecz (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Economy of Ancient Egypt: State, Administration, Institutions”

by Mahmoud Ezzamel (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian Economy: 3000–30 BCE” by Brian Muhs (2018) Amazon.com;

"Domain of Pharaoh: the Structure and Components of the Economy of Old Kingdom Egypt" by Hratch Papazian Amazon.com;

“Labour Organisation in Middle Kingdom Egypt, Illustrated, by Micòl Di Teodoro (2018) Amazon.com;

“An Outline of the Origins of Money” (Classics in Ethnographic Theory)

by Heinrich Schurtz , Enrique Martino, et al. (1898, 2024) Amazon.com;

“Economics, Anthropology and the Origin of Money as a Bargaining Counter’

by Patrick Spread (2022) Amazon.com;

“The History of Money” (1998) by Jack Weatherford (Author) Amazon.com;

“A Brief History of Money: 4,000 Years of Markets, Currencies, Debt and Crisis”

by David Orrell (2020) Amazon.com;

“Money in Ptolemaic Egypt: From the Macedonian Conquest to the End of the Third Century BC” by Sitta von Reden (2010) Amazon.com;

“Economic Life at the Dawn of History in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt: The Birth of Market Economy in the Third and Early Second Millennia BCE” by Refael (Rafi) Benvenisti and Naftali Greenwood (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy”

by Mario Liverani (2014) Amazon.com;

“Archaic Bookkeeping: Early Writing and Techniques of Economic Administration in the Ancient Near East” by Hans J. Nissen, Peter Damerow, Robert K. Englund (Author), Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

Ration System in Early Ancient Egypt (3100-2150 B.C)

Hana Vymazalova, a Czech Egyptologist, wrote: “The early Egyptian state made use of the ration system to sustain the elite, the numerous officials, and the army in a redistribution-based economy. Written evidence on labels and stone vessels from the Archaic Period indicates that a network of administrative centers existed that controlled the produce of local agricultural estates and distributed products from different parts of the country to the royal residence or the royal tomb. The agricultural domains (njwt) and administrative centers (Hwt), with appointed officials holding the title of HoA-Hwt , constituted the basis of the taxation system and of the conscription of village inhabitants for service on the king’s projects. [Source: Hana Vymazalova, a Czech Egyptologist, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

Wooden ration token from Uronarti Fort (between the 1st and 2nd cataracts in Northern Nubia) inscribed with the number of loaves it represents; Dating to the Middle Kingdom; Boston Museum of Fine Art

“At the royal residence, the title Hrj-wDb was associated with those who were in charge of the distribution of rations. Evidence indicates that from as early as the 2nd Dynasty domains had been established to support the system of direct supplying, and from the early Old Kingdom attestations have survived of agricultural domains established by rulers in order to guarantee economic support for royal projects and the administration. Kings enumerated long lists of funerary domains on the walls of their pyramid complexes; the logistical details of the transmission of agricultural products between the estates, administration, and workers, however, remain unclear.

“The organization required for massive royal projects, such as the construction of pyramid complexes, undoubtedly represented a major challenge for the Egyptian administration and economy in the Old Kingdom. A large number of officials and a huge workforce participated in the se projects, while the royal agricultural domains produced the quantity of rations required to support them. No direct evidence has survived of the system of ration-distribution at the construction sites, but some information can be traced in archaeology. Areas for brewing and bread baking were discovered at the 4 th Dynasty settlement of Heit el-Ghurab at Giza. Fish bones found on the site testify to the regular protein intake of the laborers . Officials supervising the labor would most likely have received more than the basic daily food rations, perhaps receiving grain, meat, and cloth as additional wages in accordance with their status.

“The funerary cults of deceased rulers were supplied from the domains associated with these cults, and the residence of the ruling king controlled the redistribution process. The attendants of the funerary complexes who fulfilled various cultic and bureaucratic tasks were rewarded daily through the process of the reversion of offerings. Records of distributions that survived in the Abusir archives from the late 5 th and early 6 th dynasties show daily rations written down in table-accounts, as we ll as distributions on a less frequent or irregular basis. The accounts comprise the individual rations but do not reflect the patterns according to which the system of distribution worked.

“The evidence suggests that a large part of the population was in one way or another sustained from the surplus collected by the central administration and redistributed by the royal residence together with the provincial administration centers. Though undoubtedly an exaggeration, the 500 loaves of bread, 100 jugs of beer, and half an ox, consumed daily by the magician Djedi according to the Tales of Wonder, reflect the burden that the system was apparently expected to manage. Towards the end of the Old Kingdom, the lists of both royal and private funerary d omains appeared on a larger scale in the tombs of officials and testify to an increasing control over the country’s agricultural produce through private ownership. The private provisioning of families and estates appears to be associated with the First Intermediate Period, when the central administration of a strong economically and politically unified state was no longer in operation.”

Rationed Goods in the Old Kingdom

Hana Vymazalova, a Czech Egyptologist, wrote: “The daily rations of bread and beer were recorded for the period of one month, during which each phyle (work team) served in a ten-month rotation. Half-month tables are also attested. The basic rations of the attendants of funerary temples consisted of two kinds of bread (HTA and pzn ) and ds-jugs of beer. These probably represented food redistributed from the temple’s offerings. The rank of the individuals and/or the level of importance of their service for the funerary temple are reflected in the allotment of rations: the daily rations of persons with higher sta tus could, together with bread and beer, also include meat, birds, and “good things” (xt nfrt ). [Source: Hana Vymazalova, a Czech Egyptologist, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Indications of the quantity of the daily allowances of high-ranking officials associated with these royal cults vary in the preserved documents. Up to 35 loaves of bread and one jug of beer could be allotted to a single man, but this occurred only irregularly on several days in a month . On the other hand, in a regular distribution, a holder of the title jmj-xt Hmw-nTr was allotted only two loaves of bread and one jug of beer per day. Taking into consideration the size of the bread molds and beer jars found on Old Kingdom sites, this amount of food, while seemingly suffic ient for a day’s work, would probably not constitute the entire wage of the official.

“Shorter accounts that were not displayed in the form of tables concern the daily distributions of bread, the monthly sums of the rations, and the monthly income of the funerary temples . The more than 3,000 loaves of bread (and possibly jugs of beer) mentioned in one of these monthly sums would have comfortably sustained the members of the phyles, as well as the additional staff and various officials associated with these royal cults.

“Meat seems not to have been a regular part of the diet of the attendants of the funerary temples, but cattle and poultry were slaughtered during festivals, which were relatively numerous. The accounts of meat distribution show that various butchery cuts (hind , foreleg, ribs, etc.) were given to individuals after an animal was slaughtered.

“Other commodities, such as vegetables, were probably distributed to the attendants of funerary temples on a less frequent basis. A certain quantity of fine linen was allotted to them after having been offered to the deceased king, and different sizes and qualities of cloth were divided among members of temple phyles on the occasion of festivals, either for use in their service or for their own personal use. Some of the cloth allotments were assigned to the temple statues and to the lector priests who performed recitations upon them and supervised rituals associated with them.

“The rations of grain attested in the short accounts from Abusir varied considerably, from ½ to 8 HoAt per person. The differences reflect the rank of the recipients, but absence from work and the type of work may also have been taken into consideration. The frequency of these distributions is not made explicit; monthly or weekly payments seem possible and the allotment of grain that occurs in the archives could constitute wages additional to the daily basic rations of bread and beer.

“Of a slightly earlier date are large and more complete table-accounts of the distribution of grain rations on papyri from Gebelein in Upper Egypt. The tables comprise long lists of the names and rations of those who served on a construction project that was part of the provincial administration. The rations consisted of four kinds of grain: bSA , bSA-nfr , dDw , and dDw-nfr.

“The totals for each of the allotments over a period of 15 days show us that the highest rations of the officials reached up to four sacks and 6 ¼ HoAt , while the ration of an ordinary project attendant was 5 HoAt. In another example, the distribu tion of grain to the selected group of people occurred every other day or every third day during a given period, and consisted of quantities from 1 to 8 HoAt.”

Ration System in the Middle Kingdom (2030–1640 B.C.)

Hana Vymazalova, a Czech Egyptologist, wrote: “Evidence from the Middle Kingdom presents general features similar to those of the Old Kingdom papyrus archives, though luckily some of the documents provide us with more particulars on the ration system. In the literary text The Eloquent Peasant , ten loav es of bread, together with two jugs of beer, were assigned to the “peasant” every day when he presented his complaints, and his wife and children received 3 HoAt of grain daily during that period. Thus we can surmise that these rations represented the quantity of food considered sufficient for a man and his family during the Middle Kingdom. [Source: Hana Vymazalova, a Czech Egyptologist, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Inscriptions left by expedition leaders in the deserts and wadis tend to present a system of equal rations for all, such as, for instance, the dail y ten loaves of bread mentioned in inscription 137 at Serabit el-Khadim. Other documents, above all the wage-list in the inscription of Ameni in the Wad i Hammamat, clearly indicate that rations varied considerably in relation to the status, function, and skills of the recipients, who were arranged in categories. The above-mentioned ten loaves of bread with a certain amount of beer represented the basic wage of an unskilled worker, from which the other salaries were calculated as multiples. The large allowances ascribed to the supervisors—reaching up to 200 loaves —may indicate that salaries were given partly in commodities other than bread and beer, within a given equivalence of compensation, or that perhaps a suit of personal servants accompanied some officials, by whom they were provisioned from the given rations. Meat occurred in the diet of exp edition members, but it seems to have been an irregular addition to the rations, possibly reserved for specific days such as festivals, or perhaps “paid for” from (part of) the bread and beer allowances. Vegetables were also sent to the expeditions but no details about their distribution have survived in the evidence.

“In documents from the early Middle Kingdom, an elaborate system of units was used in calculating rewards for work. A “man-day” and trzzt-portions enabled an easy organi zation of the accounts and also the comparison of the value of different products. The basic ration seems to have been 8 trzzt for one man’s workday, and a single trzzt-portion was estimated to equal slightly over 100 grams. The Reisner papyri record the use of man-days and the trzzt-compensation-units system. It is not quite clear from these documents whether the trzzt payments covered only the basic rations or also included extra salary-allowances, since the remains of an account of cloth and a small account of grain also partly survived on the papyri. A group of soldiers mentioned in the Harhotep documents received large amounts of dates in addition to their regular daily rations of grain (bSA , wheat, barley, and emmer). The rations of priests and officials associated with the funerary complex at el-Lahun included bread and beer calculated in a 2:1 ratio. Less than one loaf was the smallest ration for a temple attendant, while the jmj-r Hwt-nTr was supplied with 16 ⅔ loaves and half that amount of beer in sDA-jugs daily.

_-_TIMEA.jpg)

brick-making

“Late Middle Kingdom documents associated with the administration of a royal household show the daily allowances of the members of the royal family and high officials associated with the court. The rations included bread, beer, and various cakes. Unlike the rest of the Egyptian population, however, these elite individuals also received regular allotments of meat and vegetables. Specific quantities of provisions were given to them each day in proportion to their status. The allotments included five loaves for mid-ranking officials, ten loaves for high-ranking officials and for each of the king’s children, and 20-30 loaves for the king’s wife . In addition, one to two jugs of beer, together with five portions of meat, were allotted to the court attendants. Regular rations from the palace are also mentioned in the narrative of Sinuhe, who was brought food three or four times a day after he returned to Egypt and was pardoned by the king. The smallest ration mentioned in P. Boulaq 18 appears to have been three bakery products daily. According to the Satire of the Trades , a similar quantity of three loaves of bread and two jugs of beer seems to have been insufficient to satisfy the young student-scribe.

“In the private sphere rations were applied in much the same way as they were by the state. Inscriptions in the tombs of officials, and documents such as the papyri of Meketra, refe r to private projects— the construction of tombs, the manufacture of tomb-equipment, and the like —the rations for which appear to have been considered as payment for work —that is, hired-service wages.

“In the Heqanakht papyri we find the term aow used with the meaning “ration” or “allowance” as the payment given to individuals in return for work. This term refers elsewhere to the revenues of institutions. Documents show that the members of Heqanakht’s household and estate received wages in grain probably in addition to their daily food rations. The wages in grain were usually allocated monthly, on the first day of the lunar month (or sometimes mid-month), for the work of the preceding month. Payments in advance were rare. The largest salary mentioned in the documents consisted of 8 HoAt of grain per month, the smallest being 2 HoAt monthly.”

Ration System in New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.)

Hana Vymazalova, a Czech Egyptologist, wrote: “The ration system in the New Kingdom was similar that of the Old and Middle Kingdoms. Officials were supplied from the fields assigned to their particular offices, from the taxes collected from (or offerings given by) their subjects, and from the produce of their own private fields, vineyards, and cattle-herds. The organization of royal projects in the Valley of the Kings is relatively well attested; especially numerous are documents referring to the rations distributed among the workmen’s community of Deir el-Medina. [Source: Hana Vymazalova, a Czech Egyptologist, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Here the rations for the workers were distributed at regular intervals. Every day the workmen received sandals; every week, oils; and once a year, cloth that came from the royal treasury. Monthly payments in the form of grain came from the royal granary. Special payments sometimes occurred as favors from the ruler or from a temple. The grain allotments reflect the status of the recipients: the basic ration for a worker included 4 sacks of emmer and 1 ½ sacks of barley, while an over seer received 5 ½ sacks of emmer and 2 sacks of barley. Vegetables, water, firewood, and fish were allotted regularly, while meat represented an extra commodity . The smaller rations recorded for some of the men probably reflected wage categories or partial payments.

“Summary Although our sources on rations in ancient Egypt are rather fragmentary and reflect varying projects and work conditions, features of the general development of the ration system can be traced . The royal residence played the main role in the Old Kingdom system, which was based on the redistribution of the surplus from agricultural domains associated with royal administration centers and projects. Little can be said about the principles or termi nology of the allocations for this period. The possibility cannot be excluded that units of rations and units of work (the “man-day”), attested in later evidence, were already in use. Tables of the fulfillment of tasks of funerary temple attendants may have served in the calculation of individual ration-allotments in a manner similar to that of the man-days. The relative value of rations was calculated as the psw-quality of bread and beer, and the units of daily bread were expressed in terms of trzzt-bread since at least the early Middle Kingdom. Bread-units were used to express the value of rations, which may in reality have been given in different commodities. In the New Kingdom, private property and fields assigned to offices replaced the centralized system of domains, and the granary and treasury were in charge of the distribution of rations related to state projects.

“Rations were distributed as either daily allowances or wages/salaries; no distinction appears in the terminology in the preserved texts. Br ead and beer were distributed regularly, mostly on a daily basis, often in association with work that required the recipients to spend time away from their homes—for instance, at the royal funerary complexes or during expeditions. Grain may have been consi dered as a wage additional to the bread and beer rations, or as the main commodity. Later evidence attests to the distribution of grain as a regular payment for a month’s work. Individual rations varied between a few HoAt and several sacks of grain.

“The monthly payments at the workmen’s community of Deir el-Medina were apparently sufficient to sustain the workmen’s households. Meat was a regular component of rations only at the highest level of society, fish having been consumed instead as a regular part of the diet of workmen. Attendants of state projects received meat on an irregular basis, probably mainly in association with festivals. They were also provided infrequently with luxurious commodities such as oils and fine linen. The New Kingdom evidence ind icates yearly rations of cloth, while the Old Kingdom texts suggest cloth distributions only on the occasion of festivals.

“The food-energy value of ancient Egyptian rations has been calculated with estimated data , but generalizations can hardly be made on the basis of the preserved evidence. Rations varied in the course of time due to changes in the types of bakery products and their preparation, reflected in the development of jug-and b read-mold shapes and sizes.”

Rations for Workmen in the City of the Dead in Thebes

Workmen in the City of the Dead in Thebes received their rations each day whether they worked or not. Four times in the month they seem to have received from different officials a larger allowance (perhaps 200-300 kilograms) of fish, which appears to have formed their chief food. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Each month they also received a portion of some pulse vegetable, and a number oi jugs, which may have contained oil and beer, also some fuel and some grain. With regard however to the latter there is a story to tell. It is one of the acknowledged characteristics of modern Egypt that payments can never be made without delays, so also in old Egypt the same routine seems to have been followed with respect to the payments in kind.

The letters and the documents of the officials of the New Kingdom are full of complaints, and if geese and bread were only given out to the scribes after many complaints and appeals, we may be sure that still less consideration was shown to the workmen. The supply of grain was due to our company on the 28th of each month; in the month of Phamenoth it was delivered one day late, in Pharmuthi it was not delivered at all, and the workmen therefore went on strike, or, as the Egyptians expressed it, "stayed in their homes. "

On the 28th of Pachons the grain was paid in full, but on the 28th of Payni no grain was forthcoming and only 100 pieces of wood were supplied. The workmen then lost patience, they “set to work," and went in a body to Thebes. On the following day they appeared before “the great princes “and “the chief prophets of Amun," and made their complaint. The result was that on the 30th the great princes ordered the scribe Chaemucse to appear before them, and said to him: “Here is the grain belonging to the government, give out of it the grain-rations to the people of the necropolis. " Thus the evil was remedied, and at the end of the month the journal of the workman's company contains this notice: “We received to-day our grain-rations; we gave two boxes and a writing-tablet to the fan-bcarcr. " It is easy to understand the meaning of the last sentence; the boxes and the writingtablet were given as a present to an attendant of the governor, who persuaded his master to attend to the claims of the workmen.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024