LACK OF MONEY IN ANCIENT EGYPT

There were no coins or paper money in pharaonic Egypt. Workers tended to be paid in food, drink, oil, dried and other goods and services rather than money. Egyptians used animals, particularly sheep like money. Gold pieces have been found that are shaped like sheep. These could be considered to be an early form of money. Coins were imported and produced in the Late Period, but a system close to a monetary economy is attested only from the Ptolemaic Period onward.

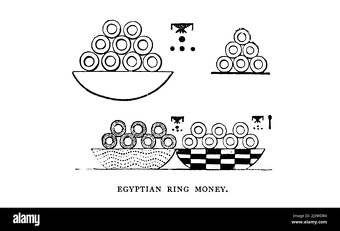

Silver rings were used in Mesopotamia and Egypt as currency hundreds of years before the first coins were struck. A wall painting from Thebes from 1,300 B.C. shows a man weighing donut-size gold rings on a balance. The use of money made trade easier between Mesopotamia, Egypt and Palestine. Archaeologists have also found a crock with bits of gold and silver, including several rod-shaped ingots of gold and silver. Egyptians also paid for things with pieces of gold and silver carried in sacks and jars and measured in deben (a traditional Egyptian measurement equal to three ounces). One deben was equal to a sack of wheat. Four or five could buy a tunic, 50, a cow.

According to the British Museum: Before coins started to circulate in ancient Egypt around 500 BC, there was a system of values based on weights of gold, silver and copper. Metal measured in units of weight known as deben (around 90 g) could be used to settle bills and to trade. Records from the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550-1295 BC) show that often the actual metal did not change hands; instead it was used to value goods for exchange. Egypt had no easily accessible source of silver, but the Egyptian word for silver, hedj, came to mean something close to 'money'. The complete ingots from el-Amarna pictured to the right weigh around 3 deben (265-286 g) and the rings seem to be fractions of the deben.

See Separate Article: RATIONING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Commerce and Economy in Ancient Egypt” by Andras Hudecz (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Economy of Ancient Egypt: State, Administration, Institutions”

by Mahmoud Ezzamel (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian Economy: 3000–30 BCE” by Brian Muhs (2018) Amazon.com;

"Domain of Pharaoh: the Structure and Components of the Economy of Old Kingdom Egypt" by Hratch Papazian Amazon.com;

“Labour Organisation in Middle Kingdom Egypt, Illustrated, by Micòl Di Teodoro (2018) Amazon.com;

“An Outline of the Origins of Money” (Classics in Ethnographic Theory)

by Heinrich Schurtz , Enrique Martino, et al. (1898, 2024) Amazon.com;

“Economics, Anthropology and the Origin of Money as a Bargaining Counter’

by Patrick Spread (2022) Amazon.com;

“The History of Money” (1998) by Jack Weatherford (Author) Amazon.com;

“A Brief History of Money: 4,000 Years of Markets, Currencies, Debt and Crisis”

by David Orrell (2020) Amazon.com;

“Money in Ptolemaic Egypt: From the Macedonian Conquest to the End of the Third Century BC” by Sitta von Reden (2010) Amazon.com;

“Economic Life at the Dawn of History in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt: The Birth of Market Economy in the Third and Early Second Millennia BCE” by Refael (Rafi) Benvenisti and Naftali Greenwood (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy”

by Mario Liverani (2014) Amazon.com;

“Archaic Bookkeeping: Early Writing and Techniques of Economic Administration in the Ancient Near East” by Hans J. Nissen, Peter Damerow, Robert K. Englund (Author), Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

Silver — Close to Money in Ancient Egypt

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: Long before coins were invented, probably in the kingdom of Lydia in western Asia Minor about the seventh century B.C., silver was widely used as a currency throughout the ancient Mediterranean. Originally, the precious metal was valued by its weight, either of cut scraps of silver and broken jewelry for small amounts or of entire ingots for larger amounts. Gold, too, was used as a means of exchange, but at least later on it was much rarer and more expensive in most regions, whereas silver was less expensive and much more common. Broken silver jewelry, scraps of silver, and silver ingots were widely used throughout the eastern Mediterranean as a form of currency many centuries before the invention of coins.[Source Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, December 12, 2020]

Egypt had no silver ores of its own, and the precious metal had to be imported. Initially it was more valuable than gold. But the silver trade appears to have quickly come to an end when the nearby kingdoms started collapsing between about 1200 and 1150 B.C. during the Late Bronze Age collapse. The ancient practice of cutting into silver ingots also appears at around the same time, and it may have been a way to check if the ingots were silver all the way through and not copper at their cores, she said. Almost three centuries later, as new powers like the Neo-Assyrians, Persians and Greek colonies started to take control of the region, the raw silver used as currency regained its purity, according to the study. From the mid-10th century B.C., "the silver was pure … signaling a previously unrecognized large-scale import of silver," the researchers wrote.

Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “Although “money” in the modern sense of the word did not exist in ancient Egypt, some of its definitive characteristics—such as standard of value and means of payment— were present.. An Egyptian word closely approaching our word “money” (and indeed often translated as such) is “silver” (HD). In the New Kingdom and later, the word was used to refer to payment, even if the payment was not actually in silver. This practice may have been a consequence of the increasing amounts of silver circulating in Egypt after foreign conquests. Until the Third Intermediate Period, however, there are no indications of a bank or government guaranteeing the value of the means of payment, or a fixed shape of that means (such as coins or bills), let alone fiduciary (as opposed to intrinsic) value. [Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

In documents from the 21st Dynasty onward, the silver used in payments is said to have come from “the Treasury of Harsaphes” (presumably in Heracleopolis); in the Saite Period a Theban treasury is referred to; and after the Persian conquest, the “treasury of Ptah” in Memphis. Müller-Wollermann has suggested that these temple treasuries acted as guarantors. Egyptian coins or other fixed forms of silver objects used for payment are not attested in these periods. However, hoards of Greek silver coins of the Late Period have been found in Egypt and there are indications of the circulation and even imitation of Greek coins at this time. Coins inspired by the Greek ones but with Egyptian inscriptions date from the 30th Dynasty and the Second Persian Period. The Ptolemies conducted their own massive production of coins and the Ptolemaic Egyptian economy came to resemble a monetary system (including banks), although payment in kind remained common practice.

Fixed-Unit Barter in Ancient Egypt

Trade was essentially barter with reference to fixed units of textile, grain, copper, silver, and gold as measures of value. During the New Kingdom a copper piece of one deben (91 grams) was in use as a measure of value. This copper piece was in the form of a spiral wire, and the weight was so firmly established that a wire of this kind served in writing as a sign for the deben. On bills of goods copper weight was used in the reckoning of payments. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Another example shows how an account was settled in buying an ox. In the latter case 119 deben of copper were to be paid up in all — 111 I deben for the animal itself, the remainder in presents and similar expenses — but of these 119 deben not one metal deben really changed hands. A stick (?) with inlaid work was substituted for 25 deben, and another of less elaborate design for 12 deben, 11 jars of honey for 11 deben, and so on. We may observe that a few of these legal tenders recur in various reckonings, for instance certain sorts of sticks, and certain kinds of paper also.

In yet Mesopotamia example, in the text quoted above, whilst an ox is said to be worth 111 deben, with additional expenses bringing it up altogether to 119 deben, an ostracon at Berlin'"' gives the value of a donkey as 40 deben. The relative value therefore of an ox and a donkey was as three to one.

Value in Ancient Egypt's Money-Barter System

Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “The exchange of commodities in Pharaonic Egypt can best be characterized as money-barter—that is, barter with reference to fixed units of value. Prices, whether formed by tradition or by demand and supply, seem to have been more stable than those in modern markets. They could be expressed, basically, in any commodity, but by far the most common were units of grain, copper, and silver (also popular was linen). The price of any given object, piece of real estate, animal, and slave could be expressed in these commodities. [Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“The value of grain fluctuated in the course of the agrarian year from low (when the harvests were brought in) to high (in the period preceding the harvests). Long-term fluctuations (such as the dramatic rise in grain prices from the reign of Ramesses III onward) may be due to failures in the government’s economic policy, or to repeated ecological stress (low Nile floods). Loans of grain between individuals could take advantage of short- and long-term fluctuations, besides requiring the payment of considerable interest (often 100 percent or more). The basic units of grain were the “sack” (XAr) and its subdivisions, the hekat (HoAt) and the oipe (ipt). In the New Kingdom, the sack was a unit of almost 80 liters, subdivided into four oipe, each of which in its turn was made up of four hekat. A further subdivision, the hin (hnw) (1/10 of the hekat, approximately 1/2 of a ter), was used for fluids, but not for grain. From the Late Period onward, grain was measured in artabe (rtb), a smaller unit than the sack, and often of uncertain capacity (estimates range between 32 and 40 liters).

“The ratio of silver to copper was stable during much of the New Kingdom (1 unit of silver against 100 units of copper), but changed towards the end of the 20th Dynasty (1 unit of silver against 60 of copper). One unit of gold equaled two of silver. It is assumed that before the late Middle Kingdom silver was more valuable than gold, because whenever earlier texts mention both metals, silver is mentioned first (it having been the custom in economic texts to start with the most expensive commodities). The reduction in the value of silver is explained by its influx from the north, which increased through Egypt’s domination in the Levant, especially after the conquests of the early New Kingdom. Egypt itself has few natural deposits of silver, as opposed to gold, a major Egyptian mineral resource.

“Gold mining areas were located in the Eastern Desert, but it was the incorporation of Nubia into the Egyptian empire that gave the pharaohs access to vast gold resources. It is even possible that the value of gold decreased slightly in the middle of the 18th Dynasty due to its massive influx. Gold was especially important to Egypt’s foreign policy as a means of financing wars and of gift- giving among the political powers of the time. Copper was abundantly available in Egypt (mainly in the Eastern Desert and Sinai) and was the prime material for tools before iron became common in the first millennium B.C..

“The units of weight used for metals were the deben (dbn: approximately 90 grams in the Ramesside Period and later; considerably less in earlier periods; cf. Graefe 1999) and its tenth part, the kite (odt). A special unit for silver was the seniu or sh(en)ati (Snatj), possibly 7.5 grams. Otherwise the kite was the unit preferred for precious metals, although gold rarely made its appearance in everyday economic traffic.

Money and the Development of Proto Money in Mesopotamia

Clay accounting tokens from Mesopotamia

Some archaeologists suggest that money was used by wealthy citizens of Mesopotamia as early as 2,500 B.C., or perhaps a few hundred years earlier. Historian Marvin Powell of Northern Illinois in De Kalb told Discover, "Silver in Mesopotamia functions like our money today. It’s a means of exchange. People use it for storage of wealth, and the use it for defining value." [Source: Heather Pringle, Discover, October 1998]

The difference between the silver rings used in Mesopotamia and earliest coins first produced in Lydia in Anatolia in the 7th century B.C. was that the Lydian coins had the stamp of the Lydian king and thus were guaranteed by an authoritative source to have a fixed value. Without the stamp of the king, people were reluctant to take the money at face value from a stranger.

Archaeologists have had a difficult time sorting out information on ancient money because, unlike pottery or utensils, found in abundant supply at archeological sites, they didn't thrown them out.

The earliest form of trade was barter. The earliest known proto-money are clay token excavated from the floors of villages houses and city temples in the Near East. The tokens served as counters and perhaps as promissory notes used before writing was developed. The tokens came in different sizes and shapes.

See Separate Article: MONEY IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA: VALUE, FORMS, DEVELOPMENT africame.factsanddetails.com

3200-Year-Old “Counterfeit” Silver Found Egypt-Controlled Canaan

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: A shortage of silver caused by the collapse of leading Bronze Age civilizations around the eastern Mediterranean about 1200 B.C. resulted in the original "dirty money" — several hundreds of years before coins had been invented. The ancient counterfeiting was revealed by archaeologist Tzilla Eshel, then a doctoral student at the University of Haifa, who studied the chemical composition of 35 buried hoards of Bronze Age silver found at archaeological sites around Israel. [Source Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, December 12, 2020]

In eight of the hoards — dating from the time of the "Late Bronze Age collapse," when the region's most powerful kingdoms suffered often-violent demises — had been deliberately debased, with cheaper alloys of copper substituted for much of the silver and an outer surface that looked like pure silver. Because the hoards date back to the when the region, then known as Canaan, was ruled by ancient Egypt, the researchers think this deception originated with the Egyptian rulers, possibly to disguise the fact that their supplies of the precious silver widely used as currency were failing. Eshel told Live Science. “continued after the Egyptians left Canaan, but they were probably the ones who initiated it."

The research by Eshel and her colleagues was be published in the January 2021 issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science. The scientists identified two of the earliest debased silver hoards: one from Beit Shean in northern Israel and another from Megiddo. Both hoards dated from the 12th century B.C., Eshel said, when Egypt's New Kingdom had ruled Canaan by right of conquest for about 300 years. The Beit Shean hoard of silver, which weighs about 5.5 ounces (157 grams), contained ingots of only 40 percent silver, which had been alloyed with copper and other cheap metals. The ingots had an enriched silver surface but a copper-rich core that may have been achieved by slowly cooling the ingot after it was melted and poured out. The Megiddo hoard, which weighed 3.4 ounces (98 grams) had an even lower amount of silver — around 20 percent. But the debasement had been disguised by the addition of the elemental metal arsenic, which gives a silvery shine to copper.

Both methods of silver debasement would have taken a considerable amount of work and knowledge to achieve, Eshel said. "They are both quite sophisticated methods, but it could have been that the arsenic [method] was easier."

Eshel suspects that the practice of debasing silver used as currency became accepted and then widespread as the shortage of silver continued in Canaan. "I think it may have started as a forgery or counterfeiting, and then maybe it became a convention over time," she said. "I don't think you can produce silver-copper-arsenic ores for over 250 years and that no one would notice, because it corrodes [by turning green] over time."

The reasons for the Late Bronze Age collapse about 3,200 years ago in the eastern Mediterranean are hotly debated. Economic disruptions, droughts, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and piracy have all been blamed for the sudden end of many powerful kingdoms in the region, including the collapse of the Hittite Empire in Anatolia, the end of the ancient Egyptian period of the New Kingdom, and the fall of the Mycenaean culture in Greece.

Payments in Ancient Egypt’s Barter- and Ration-Based, Mixed Economy

Documentation from the New Kingdom, mainly in form of government records and administrative texts indicates that ancient Egypt enjoyed had a barter- and ration-based, “mixed economy.” Sally Katary of Laurentian University in Ontario wrote: “The economic system fostered a complex system of economic interdependency wherein market forces played a complementary role: thus it was a “mixed” rather than a redistributive economy.” [Source: Sally Katary, Laurentian University of Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“The Egyptians engaged in barter or “money-barter,” the latter representing “an intermediate stage in the progress from a barter economy to a money economy…a stage in a theoretically evolutionary development”. While there is some evidence that taxes might have been paid in gold and silver (among other commodities) by towns and villages and gold occurs in official texts most often in association with officials at the southern frontier, this was not the case with ordinary individuals. Taxes in “money” were unknown until the Third Intermediate Period.”

Private exchange could probably take place everywhere and at any time. Sales or rentals of expensive items, however, would be effected with witnesses present, and might involve the taking of an oath on the part of the seller or renter promising that there were no claims by third parties on the item transferred. These were oral conventions (reflected in the unique textual documentation from Ramesside Deir el-Medina) until after the New Kingdom, when they became fixed parts of written contracts. [

José Miguel Parra wrote in National Geographic: The boat captain Merer, who based on the Red Sea 4,600 years ago, “carefully kept track of how his crew was paid. Since there was no currency in pharaonic Egypt, salary payments were made generally in measures of grain. There was a basic unit, the “ration,” and the worker received more or less according to their category on the administrative ladder. According to the papyri, the workers’ basic diet was hedj (leavened bread), pesem (flat bread), various meats, dates, honey, and legumes, all washed down with beer. [Source: José Miguel Parra, National Geographic, February 23, 2024]

According to Live Science: A tomb dating back over 3,200 years was built for an official named Ptah-M-Wia. He was a senior official during the reign of pharaoh Ramses II. Ptah-M-Wia was head of the treasury centuries before the invention of minted coins; at that time people made payments with goods, rations or precious metals. Ptah-M-Wia was in charge of making "divine offerings" at one of the temples built by Ramses II at Thebes In the remains of Ptah-M-Wia's tomb, archaeologists found a series of wall paintings showing people leading cattle and other animals to be slaughtered. This scene could be related to Ptah-M-Wia's position as livestock supervisor. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, November 2, 2021]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024