Home | Category: Economic, Agriculture and Trade

MONEY IN MESOPOTAMIA

Among the Sumerians economic units of measure were the 1) gur, a unit of volume roughly equal to 26 bushels; 2) kug or ku, silver or money; and 3) gin or gig, a small axe head used as money roughly equal to a shekel. John Alan Halloran wrote in sumerian.org: “From the Ur III period we have tablets from different places and times that give the silver equivalents of different quantities of different commodities.During the Ur III period, the state was the main creditor. The state supplied so much land or so many animals to the individual, who then had to pay the state back. [Source: John Alan Halloran, sumerian.org]

Silver rings were used in Mesopotamia and Egypt as currency about 2000 years before the first coins were struck. Some archaeologists suggest that money was used by wealthy citizens of Mesopotamia as early as 2,500 B.C., or perhaps a few hundred years earlier. Historian Marvin Powell of Northern Illinois in De Kalb told Discover, "Silver in Mesopotamia functions like our money today. It’s a means of exchange. People use it for storage of wealth, and the use it for defining value."[Source: Heather Pringle, Discover, October 1998]

According to the Austrian Archaeological Institute, the earliest known coins were produced in about the seventh century B.C. in the kingdom of Lydia, in present-day Turkey, and in the ancient Greek cities of the nearby Ionian coast. The first coins were made of electrum, a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver. Pure silver became standard in later centuries. The difference between the silver rings used in Mesopotamia and earliest coins first produced in Lydia in the 7th century B.C. was that the Lydian coins had the stamp of the Lydian king and thus were guaranteed by an authoritative source to have a fixed value. Without the stamp of the king, people were reluctant to take the money at face value from a stranger.

Archaeologists have had a difficult time sorting out information on ancient money because, unlike pottery or utensils, found in abundant supply at archeological sites, they didn't thrown them out.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“An Outline of the Origins of Money” (Classics in Ethnographic Theory)

by Heinrich Schurtz , Enrique Martino, et al. (1898, 2024) Amazon.com;

“Economics, Anthropology and the Origin of Money as a Bargaining Counter’

by Patrick Spread (2022) Amazon.com;

“The History of Money” (1998) by Jack Weatherford (Author) Amazon.com;

“A Brief History of Money: 4,000 Years of Markets, Currencies, Debt and Crisis”

by David Orrell (2020) Amazon.com;

“Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History” by Nicholas Postgate (1994) Amazon.com;

“Economy and Society of Ancient” Mesopotamia (Studies in Ancient Near Eastern Records) by Steven Garfinkle and Gonzalo Rubio (2025) Amazon.com;

“Economic Life at the Dawn of History in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt: The Birth of Market Economy in the Third and Early Second Millennia BCE” by Refael (Rafi) Benvenisti and Naftali Greenwood (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian Woe; a Study of the Origin of Certain Banking Practices and of Their Effect on the Events of Ancient History Written in the Light of the Present Day” by David Astle | (1975) Amazon.com;

“Ledgers and Prices: Early Mesopotamian Merchant Accounts” by Daniel C. Snell (1982) Amazon.com;

“Selected Business Documents On the Neo-Babylonian Period” by Ungnad Arthur (2022) Amazon.com;

“Neo-Babylonian Letters and Contracts from the Eanna Archive” (Yale Oriental Series: Cuneiform Texts) by Eckart Frahm and Michael Jursa (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Rental Houses in the Neo-Babylonian Period (VI-V Centuries BC)” by Stefan Zawadzki (2018) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City“ by Gwendolyn Leick (2001) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

Development of Proto Money

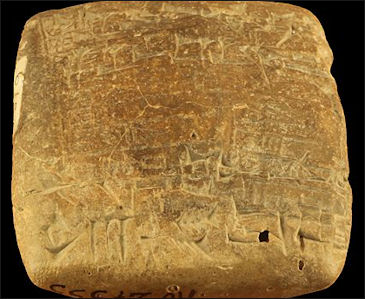

Clay accounting tokens The earliest form of trade was barter. The earliest known proto-money are clay token excavated from the floors of villages houses and city temples in the Near East. The tokens served as counters and perhaps as promissory notes used before writing was developed. The tokens came in different sizes and shapes.

Early Mesopotamians who lived in the Fertile Crescent before the rise of the first cities employed five token types that represented different amounts of the three main traded goods: grain, human labor and livestock such as goats and sheep.

Clay tokens, described by some scholars as the world's first money, found in Susa, Iran have been dated to 3300 B.C. One was equivalent to one sheep. Others represented a jar of oil, a measure of metal, a measure of honey, and different garments.

In the Mesopotamian cities, there were 16 main types of tokens and dozens of sub categories for things like honey, trussed duck, sheep's milk, rope, garments, bread, textiles, furniture, mats, beds, perfume and metals.

Development of Money and the Idea Behind it

Thomas Wyrick, an economist at Southwestern Missouri State University told Discover, "If there were a thousand different goods being traded up and down the street, people could set the price in a thousand different ways because in a barter economy each good is priced in terms of other goods. So one pair of sandals equals ten dates, equals one quart of wheat, equals two quarts of bitumen, and so on."

"Which is the best price? It's so complex that people don't know if they are getting a good deal. For the first time in history, we've got a large number of goods. And for the first time, we have so many prices that it overwhelms the human mind. People needed some standard way of stating value."

In Mesopotamia, silver became the standard of value sometime between 3100 B.C. and 2500 B.C. along with barley. Silver was used because it was a prized decorative material, it was portable and the supply of it was relatively constant and predictable from year to year.

Sometime before 2500 B.C. a shekel of silver became the standard currency. Tablets listed the price of timber and grains in shekels of silver. A shekel was equal to about one third of an ounce, or little more than three pennies in terms of weight. One month of labor was worth 1 shekel. A liter of barely sold for 3/100ths of shekel. A slave sold for between 10 and 20 shekels.

No long after shekels appeared as a means of exchange, kings began levying fines in shekels as a punishment. Around 2000 B.C., in the city of Eshnunna, a man who bit another man's nose was fined 60 shekels. A man who slapped another man in the face had to pay up 20 shekels.

Value and Forms of Money on Ancient Mesopotamia

A memorandum signed by “Basia, the son of Rikhi,” furnishes us with the relative value of gold and silver in the age of Nebuchadnezzar. “Two shekels and a quarter of gold for twenty-five shekels and three-quarters of silver, one shekel worn and deficient in weight for seven shekels of silver, two and a quarter shekels, also worn, for twenty-two and threequarters shekels of silver; in all five and a half shekels of gold for fiftyfive and a half shekels of silver.” Gold, therefore, at this time would have been worth about eleven times more than silver. A few years later, however, in the eleventh year of Nabonidos, the proportion had risen and was twelve to one. We learn this from a statement that the goldsmith Nebo-edhernapisti had received in that year, on the 10th day of Ab, 1 shekel of gold, in 5-shekel pieces, for 12 shekels of silver. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The coinage, if we may use such a term, was the same in both metals, the talent being divided into 60 manehs and the maneh into 60 shekels. There seems also to have been a bronze coinage, at all events in the later age of Assyria and Babylonia, but the references to it are very scanty, and silver was the ordinary medium of exchange. One of the contract-tablets, however, which have come from Assyria and is dated in the year 676 B.C., relates to the loan of 2 talents of bronze from the treasury of Ishtar at Arbela, which were to be repaid two months afterward. Failing this, interest was to be charged upon them at the rate of thirty-three and a third per cent., and it is implied that the payment was to be in bronze.

In connection with that “goodly Babylonish garment” which was carried away by Achan from among the spoils of Jericho. It is probable that the shekels and manehs of Babylonia were originally cast in the same tongue-like form. In Egypt they were in the shape of rings and spirals, but there is no evidence that the use of the latter extended beyond the valley of the Nile. In Western Asia it was rather bars of metal that were employed. At first the value of the bar had to be determined by its being weighed each time that it changed hands. But it soon came to be stamped with an official indication of its weight and value.

Ring Money in Mesopotamia

Receipt for clothes In the early days of shekels, people carried pieces of metal in bags and amounts were measured out on scales with stones as countermeasures on the other side. Between 2800 B.C. and 2500 B.C., pieces of silver were caste a standard weight, usually in the form of rings or coils called “har” on tablets. These rings, worth between 1 and 60 shekels, were used primarily by the rich to make big purchases. They came in a number of different forms: large ones with triangular ridges, thin coils.

A 3,700-year-old tablet from the Euphrates River town of Sippar recorded a bill of sale of a woman who bought some land with a silver ring, worth the equivalent of 60 months wages for an ordinary worker, that she received from her parents.

To pay their bills ordinary people used less valuable money made of tin, copper or bronze. Barley was also used as currency. The advantage with it was that small weighing errors made little difference and it was difficult to cheat someone.

The use of money made trade easier between city-states and kingdoms and well as between Mesopotamia, Egypt and Palestine.

Problems with Money

The main problem with silver is that it was so valuable that weighing errors or impure silver should translate to a large amount of lost value. Some people tried to purposely cheat others by adding other metals into gold or silver or even substituting look-a-like metals.

Fraud and cheating were so prevalent in the ancient world that there are eight passages in the Old Testament that forbid tampering with scales or substituting lighter for heavier stones.

People often fell into debt — a conclusion based on numerous tablet letters describing people in various kinds of trouble for falling into debt. Many debtors became slaves. The situation got so out of hand in Babylon that King Hammurabi decreed that no one could be enslaved for more than three years for debt. Other cities, with residents racked by debt, issued moratoriums on all outstanding bills.

Talents, Maneh and Shekels

The talent, maneh, and shekel were originally weights, and had been adopted by the Semites from their Sumerian predecessors. They form part of that sexagesimal system of numeration which lay at the root of Babylonian mathematics and was as old as the invention of writing. So thoroughly was sixty regarded as the unit of calculation that it was denoted by the same single wedge or upright line as that which stood for “one.” Wherever the sexagesimal system of notation prevailed we may see an evidence of the influence of Babylonian culture. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

It was the maneh, however, and not the talent, which was adopted as the standard. The talent, in fact, was too heavy for such a purpose; it implied too considerable an amount of precious metal and was too seldom employed in the daily business of life. The Babylonian, accordingly, counted up from the maneh to the talent and down to the shekel. The standard weight of the maneh, which continued in use up to the latest days of Babylonian history, had been fixed by Dungi, of the dynasty of Ur, about 2700 B.C.

An inscription on a large cone of darkgreen stone, now in the British Museum, tells us that the cone represents “one maneh standard weight, the property of Marduk-sar-ilani, and a duplicate of the weight which Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, the son of Nabopolassar, king of Babylon, had made in exact imitation of the standard weight established by the deified Dungi, an earlier king.” The stone now weighs 978.309 grammes, which, making the requisite deductions for the wear and tear of time, would give 980 grammes, or rather more than 2 pounds 2 ounces avoirdupois. The Babylonian maneh, as fixed by Dungi and Nebuchadnezzar, thus agrees in weight rather with the Hebrew maneh of gold than with the “royal” maneh, which was equivalent to 2 pounds 7½ ounces. It was not, however, the only maneh in use in Babylonia. Besides the “heavy” or “royal” maneh there was also a “light” maneh, like the Hebrew silver maneh of 1 pound 11 ounces, while the Assyrian contract-tablets make mention of “the maneh of Carchemish,” which was introduced into Assyria after the conquest of the Hittite capital in 717 B.C. Mr. Barclay V. Head has pointed out that this latter maneh was known in Asia Minor as far as the shores of the Ægean, and that the “tongues” or bars of silver found by Dr. Schliemann on the site of Troy are shekels made in accordance with it.

A Cappadocian tablet found near Kaisariyeh, which is at least as early as the age of the Exodus and may go back to that of Abraham, speaks of “three shekels of sealed” or “stamped silver.” In that distant colony of Babylonian civilization, therefore, an official seal was already put upon some of the money in circulation. In the time of Nebuchadnezzar the coinage was still more advanced. There were “single shekel” pieces, pieces of “five shekels” and the like, all implying that coins were issued representing different fractions of the maneh. The maneh itself was divided into pieces of fivesixths, two-thirds, one-third, one-half, one-quarter, and three-quarters. It is often specified whether a sum of money is to be paid in single shekel pieces or in 5-shekel pieces, and the word “stamped” is sometimes added. The invention of a regular coinage is generally ascribed to the Lydians; but it was more probably due to the Babylonians, from whom both Lydians and Greeks derived their system of weights as well as the term mina or maneh.

Examining Mesopotamian Money Envelopes

Samir S. Patel wrote in Archaeology magazine: It was surely hard to keep accurate accounts before writing was developed, but Mesopotamian merchants found a way in the form of clay balls that researchers call “envelopes,” filled with tokens and impressed with seals. Dozens of these envelopes have been found, but deciphering their meaning is problematic — broken ones are difficult to reconstruct accurately and, until recently, intact ones could not be studied without first breaking them. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2014]

“Sumerologist Christopher Woods and his team from the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago are now using CT scans to peer inside 18 intact envelopes that date to more than 5,000 years ago, excavated from Choga Mish in Iran in the 1960s and 1970s. The team observed that the tokens come in a variety of shapes and sizes, and sometimes have surface incisions, all of which could represent different commodities or amounts.

“If the contents [of a transaction] were contested,” Woods writes, “the envelope could be broken open and the tokens verified.” The balls also have seal impressions around the middle and on each end, which might represent the identities of buyers, sellers, or witnesses to a transaction. More scans will help researchers build a corpus of envelopes that can be deciphered. “We are now at a point in terms of technology where we can collect more and better data using nondestructive methods than we could if we physically opened the balls,” according to Woods.

Did Modern Banking Began in Ancient Babylonian Temples?

In ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia gold, silver and other valuables were deposited in temples for safe-keeping. The history of banks can be traced to ancient Babylonian temples in the early 2nd millennium B.C.. In Babylon at the time of Hammurabi, there are records of loans made by the priests of the temple. Temples took in donations and tax revenue and amassed great wealth. Then, they redistributed these goods to people in need such as widows, orphans, and the poor. [Source: MessageTo Eagle March 7, 2016 Ancient History Facts]

After a thousand years, the priests who ran the temples had so much money that the concept of banking came up as an idea. Around the time of Hammurabi, in the 18th century B.C., the priests allowed people to take loans. Old Babylonian temples made numerous loans to poor and entrepreneurs in need. Among many other things, the Code of Hammurabi recorded interest-bearing loans.”

The text on a cuneiform tablet detailing a loan of silver, c. 1800 B.C., reads: “3 1/3 silver sigloi, at interest of 1/6 sigloi and 6 grains per sigloi, has Amurritum, servant of Ikun-pi-Istar, received on loan from Ilum-nasir. In the third month she shall pay the silver.” 1 sigloi=8.3 grams.

The loans were made at reduced below-market interest rates, lower than those offered on loans given by private individuals, and sometimes arrangements were made for the creditor to make food donations to the temple instead of repaying interest. Cuneiform records of the house of Egibi of Babylonia describe the families financial activities dated as having occurred sometime after 1000 B.C. and ending sometime during the reign of Darius I, show a “lending house” a family engaging in “professional banking.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024