Home | Category: Late Dynasties, Persians, Nubians, Ptolemies, Cleopatra, Greeks and Romans

NUBIANS ESTABLISH THEMSELVES IN MEROE AFTER BEING DRIVEN OUT OF EGYPT

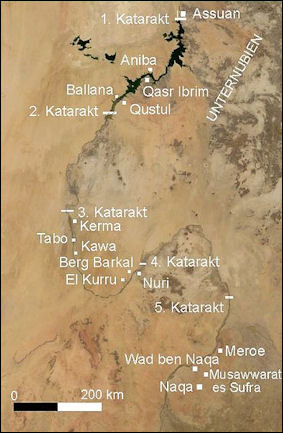

Nubia pyramids Nubia is a loosely defined region of southern Egypt and northern Sudan which used to stretch more or less 800 kilometers from Aswan to the Fourth Cataract on the Nile in Sudan but now extends from south of Luxor to Khartoum, Sudan. In Pharonic times, Nubia was known as the ancient kingdom of Kush. Beginning in the Middle Kingdom the ancient Egyptians obtained gold from Nubia. Gold was called “nub” in ancient Egypt and may be the source of the name Nubia. Ebony, ivory, leopard skins and incenses also came from Nubia or at least were transported through it from sub-Saharan Africa.

After the Assyrians drive them from Egypt, the Nubians retreated to Napata, only to be forced farther south at the beginning of the sixth century B.C., when Pharaoh Psamtek II, part of the 26th dynasty, sacked Napata. Núria Castellano wrote in National Geographic History: The Kushites designated the city of Meroë, which sat farther south along the Nile, as the new capital. This new location was carefully considered. Not only strategically positioned at the crossroads of inland African trade routes and caravan trails from the Red Sea, the land around Meroë was also fertile and blessed with significant natural resources—iron and gold mines that fostered the development of a metals industry, especially goldworking. [Source Núria Castellano, National Geographic History]

Gradually the center of the Nubian kingdom shifted further south to below the Fourth Cataract. Meroe flourished from 270 B.C. to A.D. 350. The Nubians there produced distinctive art and built cities around artificial reservoirs. Efforts by the Persians and Romans to conquer them were unsuccessful.

Through their isolation, the Meriotes lost the use of Egyptian hieroglyphics and developed a quasi-cursive script alphabet now called Meroitic. Thus far 23 letters have been figured out using small fragments of Rossetta-stone-like tablets but the language remains largely undeciphered. It s unrelated languages used by modern Nubians and is unlike an other known languages.

RELATED ARTICLES:

TWENTIETH FIFTH DYNASTY (780 – 656 B.C.): THE KUSHITE (NUBIAN) PERIOD OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT SOURCES ON NUBIA AND ETHIOPIA africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Nubia: African Kingdoms on the Nile” by Marjorie M. Fisher, Peter Lacovara , et al. (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia” by Geoff Emberling and Bruce Williams (2021) Amazon.com;

“Nubia: Lost Civilizations” by Sarah M. Schellinger (2023) Amazon.com;

“New Perspectives on Ancient Nubia” by Aaron Brody, Solange Ashby (2024) Amazon.com;

“Nubian Pharaohs and Meroitic Kings: The Kingdom Of Kush” by Necia Desiree Harkless (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Nubian Pharaohs of Egypt: Their Lives and Afterlives” by Aidan Dodson (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt and Nubia — Fully Explained: A New History of the Nile Valley” by Adam Muksawa 2023) Amazon.com;

“Arts of Ancient Nubia” by Denise Doxey (2018) Amazon.com;

“Jewels of Ancient Nubia” by Yvonne Markowitz, Denise Doxey (2014) Amazon.com;

“Afterglow of Empire: Egypt from the Fall of the New Kingdom to the Saite Renaissance”

by Aidan Dodson (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Late New Kingdom in Egypt (c. 1300–664 BC) A Genealogical and Chronological Investigation (Oxbow Classics in Egyptology) by M. L. Bierbrier (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2017) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of Ancient Egypt” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

List of Rulers of Ancient Sudan

ancient Nubia Napatan Dynasty

Alara (Unites Upper Nubia): (785–760 B.C.)

Kashta (Unites all Nubia): (760–747 B.C.)

Piye (Rules Nubia and Egypt): (747–712 B.C.)

Shabaqo(1): (712–698 B.C.)

Shebitqo(2): (698–690 B.C.)

Taharqo (Loses control of Lower Egypt)(3): (690–664 B.C.)

Tanwetamani (Loses control of Upper Egypt): (664–653 B.C.)

Atlanersa: (653–643 B.C.)

Senkamanisken: (643–623 B.C.)

Anlaman: (623–593 B.C.)

Aspelta: (593–568 B.C.)

Irike–Amanote: (425–400 B.C.)

Harsiyotf: (400–365 B.C.)

Nastasen: (320–310 B.C.)

Meroitic Dynasty

(ca. 275 B.C.–300 A.D.

Arkamani: (275–250 B.C.)

Arnekhamani: (225–175 B.C.)

Adikhalamani

Arkamani II

Kandake (Queen) Shanakdakheto: (170–150 B.C.)

Taneyidamani: (100–75 B.C.)

Teriteqas: (50–1 B.C.)

Kandake Amanitore

Kandake Amanishakheto

Natakamani: (1–50 A.D.

Kandake Amanitore

Shorkaro

[Source: (Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2001, metmuseum.org]

Samir S. Patel wrote in Archaeology magazine: In the ancient city of Meroe in the kingdom of Kush, archaeologists have uncovered a relief of a smiling, carefully adorned woman. Indications of a slight double chin suggest that she carried a bit of extra weight, which is how royal women from Kush were often depicted. She could even be a queen or a princess, according to researchers, but determining that will require more study of the fragile palace where she was found. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2013]

Post 25th-Dynasty Nubia Timeline

8th Century B.C. Construction of the south and west cemeteries begins in Meroë, then the second city of the Kingdom of Kush, whose capital was at Napata. Núria

Queen Mernua Mummy 730 B.C.: the Nubian king, Piye, successfully invaded and conquered Egypt, extending his control to the whole Nile Valley. Piye became the first pharaoh of Egypt’s 25th dynasty (ca 770-656 B.C.), the so-called Black Pharaohs.

3rd Century B.C.: As space in Meroë’s south cemetery runs out, expansion begins in the north cemetery of the city’s growing necropolis.

250 B.C.: King Arakamani relocates the royal necropolis from near Napata to Meroë, which becomes the kingdom’s spiritual and political capital.

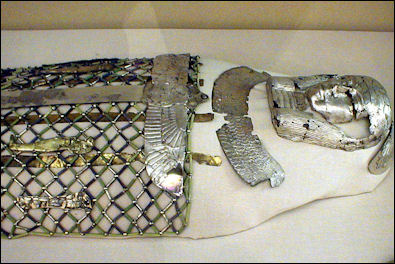

1st Century A.D.: Queen Amanirenas leads her troops against the Romans. Her successor, Amanishakheto, is buried with costly grave goods.

2nd Century A.D.: Building methods change. The Meroë pyramids are faced with brick instead of stone, and then a layer of plaster, which is painted.

A.D. 350: An invasion by the kingdom of Axum brings Meroë's dominance to an end. The city and royal necropolis are eventually abandoned.

25th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt: Nubian Rule of Egypt

During the 25th Dynasty, native princes of Kush (Nubia-modern Sudan) conquered a weak Egypt and established themselves leaders of the region. They restored ancient customs, had old texts recopied, built new temples in Thebes and revived pyramid burials. Much of the art and sculpture produced during this time was an imitation the Old and Middle Kingdom styles, some of it so well executed that even experts can’t tell the difference. The 25th dynasty ended in turmoil when an Assyrian invasion of Egypt caused it to fall from power. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

The 25th Dynasty Nubian kings were: Alara B.C. Kashta B.C. Piye 747-716 B.C. Shabako 716-702 B.C. Shabatka 702-690 B.C. Taharqa 690-664 B.C. Tantarnani 644-656 B.C.

On the 25th Dynasty, Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “ For much of Egyptian history, Nubia had been regarded merely as a source of manpower and minerals for the Egyptian state. Then, around 730 B.C., tables were turned, and the Nubian King Piye invaded and conquered Egypt. The king and his successors were, however, steeped in Egyptian culture, and viewed themselves as the renewers of ancient glories, rather than as foreign incomers. As such, they revived the ancient custom of pyramid building, which had been dropped by the pharaohs some eight centuries before-shown above are the ruins of the pyramid of Taharqa (690-664 B.C.). Despite this history, Taharqa's successor was soon driven out of Egypt by an Assyrian invasion, never to return. [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, Egyptologist, University of Bristol, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

RELATED ARTICLES:

TWENTIETH FIFTH DYNASTY (780 – 656 B.C.): THE KUSHITE (NUBIAN) PERIOD OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Nubians After the 25th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt

Napata was a city of ancient Kush at the fourth cataract of the Nile in Nubia founded by the Egyptian Amun cult for Egyptian pilgrims The Napatan Period (about 700 - 300 B.C.) is named after Napata, where where the kings were buried in small pyramids

Jeremy Pope wrote: The centuries that followed the 25th Dynasty in Nubia witnessed significant changes in the way the kingdom of Kush related to the outside world: an Assyrian invasion had expelled the Kushite kings from the Egyptian throne, and the geographical focus of Kushite royal activity then gradually shifted southward. The surviving texts, art, architecture, and other material culture from this — the Napatan — period are generous sources of information, but each body of evidence shows little connection to the others. In addition, most of the evidence for the period was first discovered in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century CE, when Sudan was under foreign domination, leading some of the earliest modern interpreters to depict the Nubian region as an isolated backwater during antiquity. During the second half of the twentieth century and the first two decades of the twenty-first century, more recent research has offered alternative interpretations of the Napatan period’s foreign relations, domestic statecraft, and chronology. [Source: Jeremy Pope, College of William & Mary, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2020]

Kushite princes and princesses continued to occupy high priestly offices in Upper Egypt even after their royal kinsmen had surrendered Lower Egypt, and indeed the appointment of some Egyptian priests was conducted under the imprimatur of the Kushite king Tanutamani years after his expulsion from the country. So loss of territory should not be equated with the immediate loss of influence or commerce.

Kathryn Howley’s thorough analysis of the shabti figurines buried during the Napatan period at Nuri has noted several features indicative of Egyptian manufacture: the use of distinctly Egyptian materials like serpentine and alabaster, the latter carved most easily soon after its quarry; a particularly fine variety of faience found also on contemporaneous shabtis in Egypt; and the appearance of shabtis with dorsal pillars , bearing only a single hoe , or with text covering only the back side — all characteristics that first emerged in Egypt after the Kushite kings had been driven from Egyptian soil. Likewise, Cara Sargent’s grammatical study of Kushite royal inscriptions has revealed that “there are few, if any, linguistic anomalies in the Classical Egyptian Napatan texts that do not also occur in contemporary Egyptian texts,” so she proposes that throughout the era “Napatans were ‘keeping pace’ linguistically with their northern neighbors”. Kushite use of Egyptian language and manufactures during the Napatan period was not the mere reminiscence of an earlier golden era, but instead the product of ongoing exchange with Egyptian neighbors and contemporaries to the north.

In addition to linguistic and commercial exchange, the Napatan era also witnessed direct military conflict between Egypt and Nubia. During the early sixth century B.C., the Egyptian king Psammetichus II orchestrated an invasion of Nubian territory that is attested in multiple graffiti and royal inscriptions. At the very least, the evidence of material culture indicates that Psammetichus II’s southward march achieved Egyptian control of Lower Nubia’s riverine fortresses for at least the next century.

After the construction of Nastasen’s pyramid, scholars do not agree on the sequence of kings or even the total number of them who ruled, and the uncertainty is exacerbated by the fact that several of the most conspicuous monuments on the Nubian landscape bear no surviving royal names. Foremost among these is the largest tomb (and only surviving pyramid) at (el-)Kurru, which has been dated provisionally to Nastasen’s successor through stylistic analysis of its decorated chapel . The reuse of Kurru after three centuries at Nuri may signal another dynastic struggle between branches of the royal family, but the details remain wholly mysterious, and Kurru seems to have been abandoned once again in the very next generation.

Meroitic and Napatan Periods

Josefine Kuckertz wrote: The Meroitic Period, which lasted from the third century B.C. to around the mid-fourth century CE, comprises the second of two phases of Kushite empire in the territory of what is today Sudan, the first phase comprising the Napatan era (around 655 – 300 B.C.).[Source: Josefine Kuckertz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2021]

While Meroitic culture reflects both Napatan influence and that of periods of Egyptian colonization (during Egypt’s New Kingdom, around 1550 – 1070 B.C.), it is characterized by the emergence of indigenous cultural elements. These include an indigenous script as well as ideological features such as concepts of kingship, burial customs, and the introduction of indigenous deities into the old Egypto-centric pantheon. Meroitic rulers were buried in cemeteries in the regions of Barkal and Meroe.

The shift of burial grounds from the vicinity of Barkal to Meroe has led scholars to designate the period and culture as “Meroitic.” There was, however, no cultural break with former times, but rather a continuation and development of prevailing cultural features with the addition of new elements. Special focus is laid on the border area between Ptolemaic and, later, Roman Egypt and the Meroitic Empire, in which both power structures had interests. The politics of both states in Lower Nubia — today territory held by Egypt and Sudan — were of varied intensity during the around 650 years of the Meroitic Period. Documentation of Meroitic history is hindered by our as yet insufficient understanding of Meroitic texts and thus relies heavily on archaeological data and the factual remains of art and architecture. In general, our knowledge is uneven: some periods are well documented, while for others we have little to no information.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Meroe and Egypt” by Josefine Kuckertz escholarship.org

Meroe: UNESCO World Heritage Site

Featuring royal tombs and steep-side slender pyramids, the wealthy Nile city of Meroë was the capital of the ancient Nubian kingdom of Kush and rival to Egypt. Inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2011, it was the Kush seat of power and lively trade and cultural center that thrived for centuries and now sits in a semi-desert landscape between the Nile and Atbara rivers, According to UNESCO: The Island of Meroe is the heartland of the Kingdom of Kush, a major power in the ancient world from the 8th century B.C. to the A.D. 4th century. Meroe became the principal residence of the rulers, and from the 3rd century B.C. onwards it was the site of most royal burials.

The property consists of three separate site components: 1) Meroe, the capital, which includes the town and cemetery site, and 2) Musawwarat es-Sufra and 3) Naqa, two associated settlements and religious centres. The Meroe cemetery, Musawwarat es-Sufra, and Naqa are located in a semi-desert, set against reddish-brown hills and contrasting with the green bushes that cover them, whilst the Meroe town site is part of a riverine landscape.

These three sites comprise the best preserved relics of the Kingdom of Kush, encompassing a wide range of architectural forms, including pyramids, temples, palaces, and industrial areas that shaped the political, religious, social, artistic and technological scene of the Middle and Northern Nile Valley for more than 1000 years (8th century B.C.-A.D. 4th century). These architectural structures, the applied iconography and evidence of production and trade, including ceramics and iron-works, testify to the wealth and power of the Kushite State. The water reservoirs in addition contribute to the understanding of the palaeoclimate and hydrological regime in the area in the later centuries B.C. and the first A.D. few centuries.

The Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe are important because 1) they reflect the interchange of ideas and contact between Sub-Saharan Africa and the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern worlds, along a major trade corridor over a very long period of time. The interaction of local and foreign influences is demonstrated by the preserved architectural remains and their iconography. 2) The property with its wide range of monument types, well preserved buildings, and potential for future excavation and research, contributes an exceptional testimony to the wealth and power of the former Kushite state and its extensive contacts with African, Mediterranean and Middle Eastern societies. The Kushite civilization was largely expunged by the arrival of Christianity on the Middle Nile in the 6th century CE.

3)The pyramids at Meroe are outstanding examples of Kushite funerary monuments, which illustrate the association with the well preserved remains of the urban centre of the Kushite capital city, Meroe. The architectural remains at the three site components illustrate the juxtaposition of structural and decorative elements from Pharaonic Egypt, Greece, and Rome as well as from Kush itself, and through this represent a significant reference of early exchange and diffusion of styles and technologies. 4) The major centres of human activity far from the Nile at Musawwarat and Naqa raise questions as to their viability in what is today an arid zone devoid of permanent human settlement. They offer the possibility, through a detailed study of the palaeoclimate, flora, and fauna, of understanding the interaction of the Kushites with their desert hinterland.

Changes in Post-25th-Dynasty Nubia

Jeremy Pope wrote: Whatever the cause, the Early Napatan regime buried at Nuri after Aspelta evidently witnessed some change in either its priorities, its fortunes, or both, between the beginning of the sixth century B.C. and the middle of the fifth. When the proverbial fog lifts from Napatan history at that century’s end during the reigns of Amannoterike and his successors, the geographic foci of recorded events have diversified noticeably. In the north, Harsiyotef and Nastasen claim to have waged campaigns against foes in Lower Nubia. In the south, Meroe is explicitly named as a royal residence in both Kushite and Greek texts, while the temples of Kawa (and soon Barkal) have fallen into disrepair, and the resumption of detailed historical reportage now targets a host of enemies from the desert and steppe, without mention of Egypt or the Mediterranean world. [Source: Jeremy Pope, College of William & Mary, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2020]

Following the 25th Dynasty’s loss of Egypt centuries earlier, these subsequent changes across the Napatan period have been characterized as a “Kushite retreat into Africa”. Yet such an interpretation implicitly assumes that an indeterminate Africa south of Napata already belonged to the Kushite kings as their natural inheritance. A 2014 study by the current author has proposed instead that the Keraba and Butana regions may have been zones of active expansion for kings of the Napatan period, “rather than a territorial bequest from their Twenty-Fifth Dynasty forebears”. If this hypothesis withstands further scrutiny, then it would recast the Napatan period as one of territorial growth in at least one direction — the south.

During the reigns of Amannoterike, Harsiyotef, and Nastasen, several military campaigns were narrated against named polities and leaders, including repeated appearances by the Medja , whom scholars have localized partly to the Nubian Desert. Yet most of the other toponyms and persons carefully listed and described by the Late Napatan kings are otherwise unknown to the Egyptologist, Classicist, biblicist, or Assyriologist. Indeed, when “Aithiopian” soldiers do appear in Greek texts of this Late Napatan era , many are described with weaponry and attire uncharacteristic of the Kushite troops. Even for famed episodes like Nectanebo II’s flight to “Aithiopia” in the fourth century B.C., no explicit reference is made in the Kushite royal record, and attempts to identify Nastasen’s foe, Kambasawden, with the Upper Egyptian rebel Khababash are no longer entertained by most scholars. A Greek account of an “Aithiopian” attack on Elephantine likewise finds no echo in the hieroglyphic inscriptions of Kush

Foreign affairs of the Late Napatan period thereby become not ahistorical, mythic, or timeless, but simply incongruent with Greek and Egyptian lore and consequently unfamiliar to modern ears. It can at least be hoped that future research will succeed in correlating more of the obscure toponyms of the written record with the few excavated sites of the central Sudan, bringing the archaeology of the Napatan era closer to its history.

Government of Post-25th-Dynasty Nubia

Jeremy Pope wrote: Across the same span of centuries when Kush’s foreign affairs became progressively more difficult to trace, its domestic affairs were illuminated through the surprising transparency of official record. The Napatan corpus is remarkable among the royal annals of antiquity for its detailed and relatively forthright accounts describing the investiture and legitimation of Kushite rulers — as if political traditions were being deliberately invented and reinforced through inscription. The resulting image of Napatan statecraft sometimes departs noticeably (and perhaps self-consciously) from Egyptian precedent, while yielding possible clues to Kushite traditions that had been limned only briefly in the earlier accounts of the 25th Dynasty.[Source: Jeremy Pope, College of William & Mary, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2020]

A stela erected by Aspelta at Barkal depicts the expected protocol of oracular election, but this stamp of divine approval merely culminates a much longer process in which the army deliberated over the choice of an appropriate successor, decided to bring the matter to the temple priesthood, and then presented to the god a cohort of eligible royal brethren. In its emphasis upon the elevation of the king from among this cohort, Aspelta’s account may echo a tradition recorded briefly by Taharqo in the preceding century.

Other texts show how new kings were then legitimated across the larger Napatan state beyond the town of Napata itself. Royal inscriptions commissioned by Anlamani, Amannoterike, Harsiyotef, and Nastasen depict a process in which the newly crowned king traveled downstream from Napata to Kawa, then to Pnubs, and finally (in the fourth century B.C.) to the enigmatic site of Tare, receiving royal insignia distinctive to each site: the cap-crown and dominion-scepters at Napata, the bow and arrows at Kawa, and the water skin at Pnubs. In each temple, documentation of his initial, Napatan coronation was first read aloud, so that coronation became “not a singular event binding across the realm, but a series of interdependent events each conferring localized authority”. The internal logic of this “ambulatory kingship” was first recognized by Nubiologist László Török (1992a), who further argued that the regional division of the coronation ritual might in turn reflect the regional division of Kushite governance during the Napatan era. The hypothesis is a logical one in view of the Nubian landscape, whose surviving monuments (and presumed population centers) were separated from one another by Nile cataracts, adverse currents, and stretches of intervening desert, Sahel, and steppe.

Nubia in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods

Kush prospered for centuries. Isma’il Kushkush wrote in Archaeology Magazine: During a rebellion against Ptolemaic rule in southern Egypt that lasted from 205 to 186 B.C., Meroitic rulers seized control of Lower Nubia and took possession of Philae’s temple precincts. Once Ptolemaic forces regained control of the region, the Nubians were forced to pay an annual tax to the priests at Philae. This ensured they would be allowed to continue visiting the island to worship their own gods. Prayer inscriptions left on the walls of the temples during this period were made by Greek and Egyptian officials and pilgrims, but none were left by Nubians. [Source: Isma’il Kushkush, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2021]

Núria Castellano wrote in National Geographic History: Cleopatra’s death in 30 B.C. brought change. Egypt became a province of the nascent Roman Empire, straining the fragile truce that the Kushites had brokered with Rome. Tax revolts in Upper Egypt led to Roman incursions into Kushite territory, threatening their lucrative gold mines. Meroite forces attacked Roman troops in Aswan—the most southerly frontier of the Roman world—led by the fearsome Queen Amanirenas of Meroë. In his great work Geography, the Greek scholar Strabo describes her as Queen Candace, “a masculine woman ... who had lost an eye.” This memorable commander was eventually beaten back to Meroë, but from then on, the Meroitic civilization was largely left in peace. [Source Núria Castellano, National Geographic History]

Egyptologist Solange Ashby of the University of California, Los AngelesAshby has identified several inscriptions at Philae dating to between 10 B.C. and A.D. 57 associated with the names of Nubians who were active there. Their titles indicate they were local Nubians who were leaders of cult organizations or village elders. Written in Demotic, the inscriptions were left mainly on the walls of temples dedicated to Nubian gods. They record mandatory donations to singers at temples or to specific temples, including those honoring the Nubian gods Arensnuphis and Thoth Pnubs. During this period, the forecourt of the temple of Isis was expanded, probably to accommodate the numbers of Nubians coming to worship on Philae. While there do not seem to have been Nubian priests at Philae during the early Roman period, Nubians were involved in the temple administration, and were perhaps in a position to monitor how their tithes were being spent.

The Nubians thrived until the king of Aksum destroyed Meroë, their capital around A.D. 350. After that Nubian links to Pharaonic Egypt disappeared. Meroë was abandoned in the A.D. fourth century. Nubia was Christianized in the A.D. 6th century and virtually vanished from the European historical record until the 19th century.

Collapse of the Kushite Kingdom

There are a number of reasons why the Kushite kingdom collapsed, Derek Welsby, a curator at the British Museum in London, told Live Science. One important reason is that the Kushite rulers lost several sources of revenue. A number of trade routes that had kept the Kushite rulers wealthy bypassed the Nile Valley, and instead went through areas that were not part of Kush. As a result, Kush lost out on the economic benefits, and the Kush rulers lost out on revenue opportunities. Additionally, as the economy of the Roman Empire deteriorated, trade between the Kushites and Romans declined, further draining the Kushite rulers of income. . [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, September 16, 2015]

Kush was also weakened and disintegrated from by internal rebellion amid worsening climatic conditions and invasions and conquest of the kingdom of Kush by the Noba people who introduced the Nubian languages and gave their name to Nubia itself. Because the Noba and the Blemmyes were at war with the Kushites the Aksumites took advantage of this, capturing Meroë and looting its gold, marking the end of the kingdom and its dissolution into the three polities of Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia, though the Aksumite presence in Meroe was likely short lived. Sometime after this event, the Kingdom of Alodia would gain control of the southern territory of the former Meroitic empire including parts of Eritrea. [Source Wikipedia]

As the Kushite leaders lost wealth, their ability to rule faded. Gematon was abandoned, and pyramid building throughout Sudan ceased. Wind-blown sands, which had always been a problem for those living at Gematon, covered both the town and its nearby pyramids.

Nubia Archaeology Related to Post-25th Dynasty Nubia

According to Archaeology magazine: Excavations in Sedeinga uncovered one of the largest collections of Meroitic inscriptions ever found. Known as the “city of the dead,” the 60-acre site housed an important necropolis dating to the kingdoms of Napata and Meroe, which flourished from the 7th century B.C. to the 4th century A.D. Although it is only partially understood, the newly found inscriptions are funerary in nature and contain biographical information about the deceased. [Source: Archaeology magazine, July-August 2018]

An archaeological project focused on the city of Dangeil, dating to the Kingdom of Kush, from the 3rd century B.C. to the 4th century a.d., has revealed the results of the excavation of a cemetery. So far, 52 tombs have been excavated with a great variety of grave goods, including large beer jars, a unique set of seven attached bowls, a silver signet ring, and a faience box crafted with udjat eyes, an Egyptian symbol of power and protection. Egyptian, Greco-Roman, and African cultures all influenced Kushite society in the period. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2014]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024