Home | Category: Late Dynasties, Persians, Nubians, Ptolemies, Cleopatra, Greeks and Romans

TWENTIETH FIFTH DYNASTY OF ANCIENT EGYPT (780–656 B.C.)

Nubia Today

During the 25th Dynasty, native princes of Kush (Nubia-modern Sudan) conquered a weak Egypt and established themselves leaders of the region. They restored ancient customs, had old texts recopied, built new temples in Thebes and revived pyramid burials. Much of the art and sculpture produced during this time was an imitation the Old and Middle Kingdom styles, some of it so well executed that even experts can’t tell the difference. The 25th dynasty ended in turmoil when an Assyrian invasion of Egypt caused it to fall from power. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

The 25th Dynasty Nubian kings were:

Alara B.C.

Kashta B.C.

Piye 747-716 B.C.

Shabako 716-702 B.C.

Shabatka 702-690 B.C.

Taharqa 690-664 B.C.

Tantarnani 644-656 B.C.

On the 25th Dynasty, Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “ For much of Egyptian history, Nubia had been regarded merely as a source of manpower and minerals for the Egyptian state. Then, around 730 B.C., tables were turned, and the Nubian King Piye invaded and conquered Egypt. The king and his successors were, however, steeped in Egyptian culture, and viewed themselves as the renewers of ancient glories, rather than as foreign incomers. As such, they revived the ancient custom of pyramid building, which had been dropped by the pharaohs some eight centuries before-shown above are the ruins of the pyramid of Taharqa (690-664 B.C.). Despite this history, Taharqa's successor was soon driven out of Egypt by an Assyrian invasion, never to return. [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, Egyptologist, University of Bristol, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

James Allen and Marsha Hill of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “From ca. 728 to 656 B.C., the Nubian kings of Dynasty 25 dominated Egypt. Like the Libyans before them, they governed as Egyptian pharaohs. Their control was strongest in the south. In the north, Tefnakht's successor, Bakenrenef, ruled for four years (ca. 717–713 B.C.) at Sais until Piankhy's successor, Shabaqo (ca. 712–698 B.C.), overthrew him and established Nubian control over the entire country. The accession of Shabaqo can be considered the end of the Third Intermediate Period and the beginning of the Late Period in Egypt. [Source: James Allen and Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Nubian rule, which viewed itself as restoring the true traditions of Egypt, benefited Egypt economically and was accompanied by a revival in temple building and the arts that continued throughout the Late Period. At the same time, however, the country faced a growing threat from the Assyrian empire to its east. After forty years of relative security, Nubian control—and Egypt's peace—were broken by an Assyrian invasion in ca. 671 B.C. The current pharaoh, Taharqo (ca. 690–664 B.C.), retreated south and the Assyrians established a number of local vassals to rule in their stead in the Delta. One of them, Necho I of Sais (ca. 672–664 B.C.), is recognized as the founder of the separate Dynasty 26. For the next eight years, Egypt was the battleground between Nubia and Assyria. A brutal Assyrian invasion in 663 B.C. finally ended Nubian control of the country. The last pharaoh of Dynasty 25, Tanutamani (664–653 B.C.), retreated to Napata. There, in relative isolation, he and his descendants continued to rule Nubia, eventually becoming the Meroitic civilization, which flourished in Nubia until the fourth century A.D.” \^/

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT NUBIA AND NUBIANS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT SOURCES ON NUBIA AND ETHIOPIA africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Nubian Pharaohs of Egypt: Their Lives and Afterlives” by Aidan Dodson (2023) Amazon.com;

“Nubian Pharaohs and Meroitic Kings: The Kingdom Of Kush” by Necia Desiree Harkless (2006) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt and Nubia — Fully Explained: A New History of the Nile Valley” by Adam Muksawa 2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Nubia: African Kingdoms on the Nile” by Marjorie M. Fisher, Peter Lacovara , et al. (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia” by Geoff Emberling and Bruce Williams (2021) Amazon.com;

“Nubia: Lost Civilizations” by Sarah M. Schellinger (2023) Amazon.com;

“New Perspectives on Ancient Nubia” by Aaron Brody, Solange Ashby (2024) Amazon.com;

“Arts of Ancient Nubia” by Denise Doxey (2018) Amazon.com;

“Jewels of Ancient Nubia” by Yvonne Markowitz, Denise Doxey (2014) Amazon.com;

“Afterglow of Empire: Egypt from the Fall of the New Kingdom to the Saite Renaissance”

by Aidan Dodson (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Late New Kingdom in Egypt (c. 1300–664 BC) A Genealogical and Chronological Investigation (Oxbow Classics in Egyptology) by M. L. Bierbrier (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2017) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of Ancient Egypt” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

Late Period of Ancient Egypt (712–332 B.C.)

The Late Period (712 to 332 B.C.) includes the 25th, 26th, 27th, 28th, 29th and 30th Dynasties, with one period of Nubia rule and one period of Persian rule (a second period of Persian rule occurred later). The 25th dynasty was Nubian. This marked the beginning of the Late Period. The 27th and 31st dynasties were Persian. After the 27th dynasty the Persians were expelled but returned once again. After experiencing a brief period of autonomy after the Persians were expelled the first time, Egypt was conquered again by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C.

After 1085 B.C. Egypt was divided and ruled by priests. Egyptian culture went into a period of decline. Treasuries shrunk as a result of expensive monument building and military campaigns. There were food riots and strikes. In 525 B.C., Egypt was conquered the Persians The New Kingdom was followed by the Third Intermediate Period (1075 to 715 B.C.), the Late Period (715 to 332B.C.) and the Greco-Roman Period (332 B.C. to A.D. 395).

The Late Period includes the last periods during which ancient Egypt functioned as an independent political entity. During these years, Egyptian culture was under pressure from major civilizations of the eastern Mediterranean and the Near East. The socioeconomic system, however, had a vigor, efficiency, and flexibility that ensured the success of the nation during these years of triumph and disaster. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

See Separate Article: EARLY LATE PERIOD OF ANCIENT EGYPT (712– 525 B.C.): NUBIANS, SAITE KINGS AND GREEKS africame.factsanddetails.com

List of Rulers from the 25th Dynasty and Napatan Dynasties

Late Period ca. 712–332 B.C.

Dynasty 25 (Nubian), ca. 712–664 B.C.

Shebitqo: ca. 698–690 B.C.

Taharqa (Loses control of Lower Egypt) ca.690–664 B.C.

Tanutamani (Loses control of Upper Egypt): ca. 664–653 B.C.

[Source: Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002]

Napatan Dynasty

Alara (Unites Upper Nubia) (785–760 B.C.)

Kashta (Unites all Nubia) (760–747 B.C.)

Piye (Rules Nubia and Egypt) (747–712 B.C.)

Shabaqo(1) (712–698 B.C.)

Shebitqo(2) (698–690 B.C.)

Taharqa (Loses control of Lower Egypt)(3) (690–664 B.C.)

Tanwetamani (Loses control of Upper Egypt) (664–653 B.C.)

Atlanersa (653–643 B.C.)

Senkamanisken (643–623 B.C.)

Anlaman (623–593 B.C.)

Aspelta (593–568 B.C.)

Irike–Amanote (425–400 B.C.)

Harsiyotf (400–365 B.C.)

Nastasen (320–310 B.C.)

[Source (Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2001, metmuseum.org]

Nubia and Ethiopia

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: Nubia was a region south of Egypt, which was divided by the Nile nearest the 2nd Cataract. The products of Nubia and Kush added greatly to the wealth of Egypt, particularly by providing gold, ivory, ebony, cattle, gums and semi-precious stones. Cattle were one of the major contributions made by Nubia suggesting that grasslands were more extensive in the time of the Old Kingdom. In addition, the Nile Delta below Memphis has always been one of great fertility, flanked on its eastern and western borders by wide meadowlands where goats, sheep and cattle were raised. The fertility of Nubia and it's products enriched both Egyptian and Nubian cultures which lived along the Nile. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

In some ancient texts Ethiopians are described as living south or Egypt rather than Nubians. It seems likely that the authors meant Nubians or were reporting on Nubians and Ethiopians are generally describing black Africans that lived south of Egypt. During the 25th Dynasty, Egypt was led by three Nubian list three Ethiopian kings form the twenty-fifth dynasty, Sabacon, Sebichos, and Taracos (the Tirhaka of the Old Testament).

The main accounts of Ancient Nubia and Ethiopia from classical sources are a text on the Aspalta as King of Kush, c. 600 B.C.; Herodotus, The Histories, c. 430 B.C., Book III; Strabo: Geography, A.D. 22, XVI.iv.4-17; XVII.i.53-54, ii.1-3, iii.1-11; Acts of the Apostles 8:26-39; Dio Cassius: History of Rome, c. A.D. 220, CE, Book LIV.v.4-6; Inscription of Ezana, King of Axum, c. A.D. 32; Procopius of Caesarea: History of the Wars, c. A.D. 550, Book I.xix.1, 17-22, 27-37, xx.1-13. There are also accounts by Pliny the Elder, Claudius Ptolemaeus, and the Periplus but they used the same source that Strabo did. There is also an account by Diodorus Siculus but is virtually the same as Strabo’s. [Source: Paul Halsall, Forham University]

Nubian Conquest of Egypt by King Piye

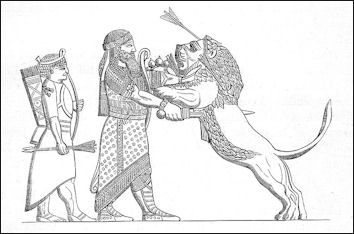

Prince Arikankharer Slaying His Enemies In the eighth century B.C., the new powerful kingdom of Napata emerged in Nubia just below the Fourth Cataract. A nearby holy mountain was believed to be the home of the ram-headed supreme god of Amun and an oracle that attracted people from all over Africa and the Middle East was established there. At this time Egypt was weak. [Sources: Robert Draper, National Geographic, February 2008; David Roberts, Smithsonian]

While a power vacuum existed in Egypt, Nubia governed itself independently as the kingdom of Kush under a line of rulers based at Napata near the fourth Cataract. Around 750 B.C., Napatan kings began expanding their territory northwards. Around 730 B.C. Napata-based King Piye (750–715 B.C.) swept through Egypt with his great army, meeting little resistance, conquering all of Egypt and Nubia from present-day Khartoum to present-day Alexandra and then withdrew to Napata.

Piye wrote, “I shall let Lower Egypt taste the taste of my fingers." After capturing one city after another along the Nile in 730 B.C., the army of King Piye stormed the great walled capital of Memphis with flaming arrows. When the city was taken Piye did an extraordinary thing he packed up his army and booty and returned to Nubia never to set foot in Egypt again, as if the whole military campaign was simply to make some kind of point; namely that he was more Egyptian than the Egyptians themselves, which by that time had grown weak and corrupt.

Egyptians described Nubians as experts with bow and arrow and Nubia itself was sometimes called Ta-Seti ("Land of the Bow"). Although Egyptian stelae refer to to Nubian leaders as "raging panthers" who attacked their enemies "like a cloudburst," they were regarded by historians as benevolent horse people who patronized the arts and were buried with their chariots. Piye reported that he chose the horses from a conquered lands rather than its women. He was buried with four of his favorite horses.

Ethnic Libyan kings reigned briefly as Dynasty 24, but after 715 B.C. the Kushites returned to Egypt under Piye's successor, Shabaqo. Shabaqo established Dynasty 25, made up of Kushite kings who ruled both their native land and all of Egypt. The Nubian dominance was short-lived. By 667 B.C. the Nubians had moved out of Egypt and were replaced by the war-loving Assyrians, whose leaders boasted "I tore up the root of Kush and not one therein escaped to submit to me." [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003]

Herodotus on the Nubian Invasion of Egypt

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “After him reigned a blind man called Anysis, of the town of that name. In his reign Egypt was invaded by Sabacos king of Ethiopia [Shabaka, the 3rd Nubian king of Egypt’s 25th Dynasty] and a great army of Ethiopians [[robably referring to Kushites or Nubians). The blind man fled to the marshes, and the Ethiopian ruled Egypt for fifty years, during which he distinguished himself for the following: he would never put to death any Egyptian wrongdoer but sentenced all, according to the severity of their offenses, to raise embankments in their native towns. Thus the towns came to stand yet higher than before; for after first being built on embankments made by the excavators of the canals in the reign of Senusret, they were yet further raised in the reign of the Ethiopian. Of the towns in Egypt that were raised, in my opinion, Bubastis is especially prominent, where there is also a temple of Bubastis, a building most worthy of note. Other temples are greater and more costly, but none more pleasing to the eye than this. Bubastis is, in the Greek language, Artemis. 138. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

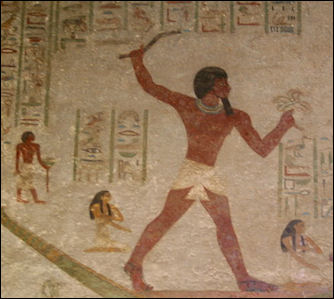

Ramses II fighting Nubians

“Her temple is of this description: except for the entrance, it stands on an island; for two channels approach it from the Nile without mixing with one another, running as far as the entryway of the temple, the one and the other flowing around it, each a hundred feet wide and shaded by trees. The outer court is sixty feet high, adorned with notable figures ten feet high. The whole circumference of the city commands a view down into the temple in its midst; for the city's level has been raised, but that of the temple has been left as it was from the first, so that it can be seen into from above. A stone wall, cut with figures, runs around it; within is a grove of very tall trees growing around a great shrine where the image of the goddess is; the temple is a square, each side measuring an eighth of a mile. A road, paved with stone, about three eighths of a mile long leads to the entrance, running eastward through the marketplace, towards the temple of Hermes; this road is about four hundred feet wide, and bordered by trees reaching to heaven. Such is this temple. 139.

“Now the departure of the Ethiopian (they said) came about in this way. After seeing in a dream one who stood over him and urged him to gather together all the Priests in Egypt and cut them in half, he fled from the country. Seeing this vision, he said, he supposed it to be a manifestation sent to him by the gods, so that he might commit sacrilege and so be punished by gods or men; he would not (he said) do so, but otherwise, for the time foretold for his rule over Egypt was now fulfilled, after which he was to depart: for when he was still in Ethiopia, the oracles that are consulted by the people of that country told him that he was fated to reign fifty years over Egypt. Seeing that this time was now completed and that he was troubled by what he saw in his dream, Sabacos departed from Egypt of his own volition. 140.

“When the Ethiopian left Egypt, the blind man (it is said) was king once more, returning from the marshes where he had lived for fifty years on an island that he built of ashes and earth; for the Egyptians who were to bring him food without the Ethiopian's knowledge were instructed by the king to bring ashes whenever they came, to add to their gift. This island was never discovered before the time of Amyrtaeus; all the kings before him sought it in vain for more than seven hundred years. The name of it is Elbo, and it is over a mile long and of an equal breadth. 141.

Black Pharaohs of Egypt

Nubian pharoahs

Piye's victories united all Egypt under the Nubian rule for three-quarters of a century. Piye and his successors became the black pharaohs of the 25th Dynasty (ca 770-656 B.C.) and the capital of Nubia was moved from Napata to Memphis. Under Nubian rule, Egyptian culture was revived.

Piye modeled himself after powerful pharaohs such as Ramses II, and claimed to be th rightful heir of Egypt. Naming himself Thutmose III, after a famous, Egyptians pharaoh, he had his soldiers purify themselves by bathing in the Nile before battle, dress in fine lines and sprinkle their bodies with water from the temple of Karnak, a site regarded as the dwelling place of the Egyptian god Amun, which Piye had selected as his own personal; deity.

When Piye died in 715 B.C. and his 35-year reign ended he was buried in an Egyptian-style pyramid. Although he had returned to Nubia after conquering Egypt, he wished to be buried in the Egyptian style. His request was honored. He was the first pharaoh in Egypt to be entombed in a pyramid in more than 500 years.

Piye was succeeded by his brother Shabaka, who embraced Egyptians ways as vigorously as Piye. He adopted the name Pepi, the name of a famous Egyptians Old Kingdom pharaoh and took up residence in the Egyptian capital of Memphis. He made grand additions to the temple in Thebes, erecting a pink granite statute of himself with a Kushite crown at Karnak, one of ancient Egypt's most sacred sites.

Dena Connors-Millard wrote: “Shabaka, also spelled Sabaka or Shebaka, was from Nubia. He was born c. 760 B.C. and died c.695 B.C. He became the first Ethiopian-born Pharaoh and began the 25th Dynasty of Egypt about 2710 years ago. Shabaka is known for his building projects such as restoring the gate at Karnak. He also promoted a return to ancient religious customs like pyramid burials. Shabaka is probably best known for the. Shabaka Stone. This is a stone with the information of Memphite beliefs carved on it. The stone was commissioned by Shabaka when it was found that the only information left of the Memphite beliefs was on a deteriorating piece of papyrus. The idea of the stone was to preserve the Memphite belief system forever. Unfortunately,the stone was later used as a mill stone and parts of the text are illegible.” [Source: Dena Connors-Millard, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

Powerful Nubian Queens

Nubian queens were thought to have great power. Because kings often married their sisters, some scholars say that power descended through the female line. Great treasures have been found in the tomb of an unidentified queen of the Napatan king Piye, who had at least five wives.

The most famous Nubian queen made here presence known in the Roman period. Núria Castellano wrote in National Geographic History: One of the most remarkable features of Meroitic civilization was its strong queens. In his Geography, Greek historian Strabo wrote of a queen called “Candace” who signed a peace treaty with the emperor Augustus. Candace, in fact, means “sister,” and was the title given to Kushite queens. There were many queens in Meroë, such as Amanirenas—the “Candace” Strabo was referring to—and her successor, Amanishakheto, whose treasure was looted in 1834. Archaeologists have recently been studying the funerary chamber of another queen, Khennuwa, whose tomb was excavated by George Reisner in 1922. [Source Núria Castellano, National Geographic History]

Yasmin Moll wrote in The Conversation: Growing up in Cairo’s Nubian community, we children didn’t hear about Cleopatra, but about Amanirenas: a warrior queen who ruled the Kingdom of Kush during the first century B.C. Queens in that ancient kingdom, encompassing what is now southern Egypt and northern Sudan, were referred to as “kandake” – the root of the English name “Candace.” Like Cleopatra, Amanirenas knew Roman generals up close. But while Cleopatra romanced them – strategically – Amanirenas fought them. She led an army up the Nile about 25 B.C. to wage battle against Roman conquerors encroaching on her kingdom. [Source: Yasmin Moll, Assistant Professor of Anthropology, University of Michigan, The Conversation, June 9, 2023]

My own favorite part of this story of Indigenous struggle against foreign imperialism involves what can only be characterized as a power move. After beating back the invading Romans, Queen Amanirenas brought back the bronze head of a statue of the emperor Augustus and had it buried under a temple doorway. Each time they entered the temple, her people could literally walk over a symbol of Roman power. That colorful tidbit illustrates those queens’ determination to defend their autonomy and territory. Amanirenas personally engaged in combat and earned the moniker “the one-eyed queen,” according to an ancient chronicler of the Roman Empire named Strabo. The kandakes were also spiritual leaders and patrons of the arts, and they supported the construction of grand monuments and temples, including pyramids.

Taharqa

sphinx of Taharqa

Piye's son Taharqa succeeded Shabaka and ruled Egypt-Nubia for 26 years. Nubian Egypt reached its pinnacle under his rule. He built monuments with images and cartouches all over Egypt and Nubia and presided over huge harvests helped by record rains and the swelling of the Nile. At Jebel Barkal, Taharqa created a temple dedicated to the goddess Mut, the consort of Amun. He also added an entrance to the Great Temple of Amun at Karnak. Perhaps the most telling evidence of his influence was an eradication campaign that was launched to wipe out all images of him in Egypt after his death.

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Taharqa was a particularly ambitious leader in this regard who presided over a kingdom that extended as far north as Palestine. He renovated and built temples throughout Egypt and Nubia, perhaps even the possible temple to Amun in Dangeil. Dangeil is the farthest south a colossal statue of Taharqa has been discovered, suggesting that it may well mark the southern extent of his kingdom. Over time, Kushite control extended even farther south, and, by the third century B.C., the capital is thought to have moved from Napata to Meroe, south of Dangeil. “We don’t know exactly when the south began to have greater influence, but it looks as if it starts to happen during the seventh century B.C.,” says Julie Anderson of the British Museum, a codirector of the dig at Dangeil. “With the statues in Dangeil and the presence of this early building, it looks as if the royalty at Napata have direct control over that area during this period.” [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2015]

Taharqa ((biblical Tharaca, Tirhaka 2 Kgs 19:9) needed lots of cedar and juniper from Lebanon to realize his building campaign. When the Assyrian ruler King Esarhaddon tried to shut down the trade, Taharqa sent troops to the southern Levant to support a revolt against the Assyrians. See BelowAn Assyrian invasion under Esarhaddon forced Taharqa to retreat. When Esarhaddon withdrew from Egypt, Taharka returned from his sanctuary in Upper Egypt and massacred all the Assyrians he could get his hands on. He controlled Egypt until he was defeated by Esarhaddon’s son, Ashurbanipal, after which he fled south to Nubia where he later died.

In 669 B.C. Esarhaddon had died on route to Egypt but his successor Ashurbanipal quickly mounted an assault on Egypt. Taharqa knew he was outnumbered this time and fled to Napata never to return to Egypt again. How Taharqa spent his final years is unknown but he was allowed to remain in power in Nubia. Like his father Piye he was buried in a pyramid.

Nubians Versus Assyrians in Egypt

The Assyrian Empire was a threat to Kushite rule. The Assyrian kings Sennacherib and Asarhaddon both attacked Egypt. In 701 B.C. , the Nubians battled the Assyrians in Eltekeh in present-day Israel and prevented the Assyrians from taking over Egypt. After the Assyrians moved on Jerusalem, where according to the Bible they looked assured of victory but, as if by miracle, suddenly retreated. Some historian have suggested they fled because they heard the Nubians were advancing towards Jerusalem. The historian Henry Aubin has argued this was a key moment in history, allowing Judaism to strengthen enough to survive the attempt by Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar to annihilate them, paving the way for Judaism to survive and Christian and Islam to develop.

Assyrians Taharqa sent troops to the southern Levant to support a revolt against the Assyrians. Esarhaddon stopped the effort and launched an attack into Egypt which Taharqa’s army pushed back in 674 B.C. Robert Draper wrote in National Geographic, “The victory clearly went to the Nubian’s head, Rebel states along the Mediterranean shared his giddiness and entered into an alliance against Esarhaddon. In 671 B.C., the Assyrians marched with their camels into the Sinai desert to quell the rebellion, Success was instant: now it was Esarhaddon who brimmed with bloodlust. He directed his troops towards the Nile Delta.”

Esarhaddon avenged Taharqa support for Palestine’s revolt and defeated Taharka’s army. Memphis was captured, along with its royal harem. In 671 B.C. The Assyrians sacked Memphis, “Taharqa and his army squared off against the Assyrians. For 15 days they fought pitched battles—“very bloody” — by Esarhaddon’s own admission. But the Nubians were pushed back all the way to Memphis. Wounded five times Taharqa escaped with his life and abandoned Memphis. In typical Assyrian fashion, Esarhaddon slaughtered the villagers and “erected piles of theirs heads.”

The Assyrians later wrote: “His queen, his harem, Ushankhuru his heir, and the rest of his sons and daughters, his property and his goods, his horses, his cattle, his sheep, in countless numbers I carried off to Assyria. The root of Kush I tore up out of Egypt.” To commemorate the event a stelae was raised that showed Taharqa’s son Ushankhuru, kneeling before the Assyrian king with a rope around his neck.

Taharqa 's successor, Tanutamun, re-entered Egypt but was immediately defeated by another Assyrian onslaught, during which Ashurbanipal, with the help of Egyptian vassals, subdued all of Egypt once again. The victors struck the names of the 25th dynasty from monuments across Egypt, destroying their statues and stelae to erase their names from history.

Aspalta, King of Kush, c. 600 B.C.

Aspelta was a ruler of the kingdom of Kush (c. 600 – c. 580 B.C.) who used titles based on those of the Egyptian Pharaohs. A text called Aspalta as King of Kush (c. 600 B.C.) reads: “Now the entire army of his majesty was in the town named Napata, in which Dedwen, Who presides over Wawat, is God — he is also the god of Kush — after the death of the Falcon [Inle-Amon] upon his throne. Now then, the trusted commanders from the midst of the army of His Majesty were six men, while the trusted commanders and overseers of fortresses were six men.... Then they said to the entire army, "Come, let us cause our lord to appear, for we are like a herd which has no herdsman!" Thereupon this army was very greatly concerned, saying, "Our lord is here with us, but we do not know him! Would that we might know him, that we might enter in under him and work for him, as It-Tjwy work for Horus, the son of Isis, after he sits upon the throne of his father Osiris! Let us give praise to his two crowns." Then the army of His Majesty all said with one voice, "Still there is this god Amon-Re, Lord of the Thrones of It-Tjwy, Resident in Napata. He is also a god of Kush. Come, let us go to him. We cannot do a thing without him, but a good fortune comes from the god. He is the god of the kings of Kush since the time of Re. It is he who will guide us. In his hands is the kingship of Kush, which he has given to the son whom he loves.... [Source: Schäfer, “A History of Ancient Aethiopian Kingship” (London, 1905), pp. 81-100]

KhnoumhotepII “So the commanders of His Majesty and the officials of the palace went to the Temple of Amon. They found the prophets and the major priests waiting outside the temple. They said to them, "Pray, may this god, Amon-Re, Resident in Napata, come, to permit that he give us our lord, to revive us, to build the temples of all the gods and goddesses of Kemet, and to present their divine offerings! We cannot do a thing without this god. It is he who guides us. Then the prophets and the major priests entered into the temple, that they might perform every rite of his purification and his censing. Then the commanders of His Majesty and the officials of the palace entered into the temple and put themselves upon their bellies before this god. They said, "We have come to you, O Amon-Re, Lord of the Thrones of It-Tjwy, Resident in Napata, that you might give to us a lord, to revive us, to build the temples of the gods of Kemet and Rekhyt, and to present divine offerings. That beneficent office is in your hands — may you give it to your son whom you love!"

“Then they offered the king's brothers before this god, but he did not take one of them. For a second time there was offered the king's brother, son of Amon, and child of Mut, Lady of Heaven, the Son of Re, Aspalta, living forever. Then this god, Amon-Re, Lord of the Thrones of It-Tjwy, said, "He is your king. It is he who will revive you. It is he who will build every temple of Kemet and Rekhyt. It is he who will present their divine offerings. His father was my son, the Son of Re, Inle-Amon, the triumphant. His mother is the king's sister, king's mother, Kandake of Kush, and Daughter of Re, Nensela, living forever, He is your lord."

Temples in the 25th Dynasty

Christiane Zivie-Coche wrote: The Kushite kings exercised their power primarily at Thebes, although Memphis was also the object of their attention, as indicated by the “Shabaqo Stone”, a copy of an ancient mythological text, the cosmological part probably Ramesside. A further indication of the importance of the northern city was a restoration decree, on a stele of Taharqa, for the Memphite temple of “Amun at the head of the gods”. Previously, Piankhy had recorded his offerings in all the temples of the conquered land on his victory stele, found at Gebel Barkal. [Source: Christiane Zivie-Coche, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris Sorbonne, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“In the temple of Karnak, Taharqa built a western colonnade in the temple court west of the second pylon, of which only one column is extant today, while of the other columns only the lower parts and remains of the “screen” walls that once connected the columns have been preserved. Three additional colonnades at each of the other cardinal points completed the design. A similar construction was built in front of the temple of Montu in north Karnak and at the entrance of the 18th-Dynasty temple at Medinet Habu. The most original monument is the Edifice of Taharqa, built near the sacred lake of Karnak. At present only the subterranean part of the structure is extant, the superstructure having been for the most part destroyed. There is no building that parallels this unique structure; we therefore have no comparison on which to base a reconstruction of the upper part. The underground rooms are dedicated to Amun- Ra, narrowly associated with Osiris. The walls are decorated with the “Litany of Ra”, a hymn to the ten “bas” of Amun, and the first known representation of the Mount of “Djeme”, which was thought to cover the cenotaph of Osiris on the west bank of the Nile at Thebes. The fundamental aspects of the theology of Amun that become manifest during the Late Period are found for the first time on the walls of the Edifice of Taharqa. A restoration text of Montuemhat, governor of Thebes, inscribed in one of the small rooms of the Mut temple, relates a temple inventory that took place during the reign of Taharqa as part of a program of repairs executed at that time.

“The rulers of the 25th Dynasty also constructed several temples in southern Egypt and northern Sudan, at Tabo, Kawa, and Sanam. These were mostly dedicated to Amun and built on the classical Egyptian model, with the exception of particular details that might reflect relationships with local cults. At the foot of the sacred mountain at Gebel Barkal the cult spaces were transformed or rebuilt. The style of sculpture and relief is characterized by the search for a certain classicism, of which the paradigms hark back to the Old Kingdom (Memphis) and Middle Kingdom (Thebes). This taste for archaism continued in the succeeding dynasty.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions”edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024