DOMESTICATED ANIMALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

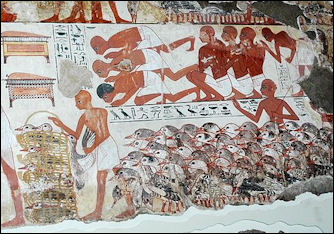

Cow calving

Cattle was raised on estates, primarily in the delta, in ancient Egypt to supply royalty with meat. Reliefs show men milking cows and slaughtering cattle on a large scale at a royal processing center. Egyptians used animals, particularly sheep, for money. Gold pieces have been that are shaped like sheep. These are believed to have been early money. Egyptian farmers tried to domesticate other animals such as hyenas, gazelles and cranes but gave up after the Old Kingdom.

Cattle were part of the staple diet of the Egyptians, suggesting that grazing land was available for the Egyptians during the times when the Nile receded. However, during the inundation, cattle were brought to the higher levels of the flood plain area and were often fed the grains harvested from the previous year.” [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

See Separate Articles: LIVESTOCK IN ANCIENT EGYPT factsanddetails.com ; HUNTING, NETTING AND FISHING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Domestic Plants and Animals: The Egyptian Origins” by Douglas J. Brewer, Donald B. Redford, et al. (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of the First Farmer-Herders in Egypt: New Insights into the Fayum Epipalaeolithic and Neolithic” by N. Shirai (2010) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Neolithic Revolution in the Near East: Transforming the Human Landscape”

by Alan H. Simmons and Dr. Ofer Bar-Yosef (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Process of Animal Domestication” by Marcelo Sánchez-Villagra (2022) Amazon.com;

“Cows, Pigs, Wars, and Witches: The Riddles of Culture” by Marvin Harris (1989) Amazon.com;

“Domesticated: Evolution in a Man-Made World” by Richard C. Francis Amazon.com;

“Evolution of Domesticated Animals” by I. L. Mason | Jan 1, 1984 Amazon.com;

“Archaeology and Biology of the Aurochs by Gerd-C. Weniger (1999) Amazon.com;

“Aurochs and Auks: Essays on Mortality and Extinction”

by John Burnside (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Cow: A Natural and Cultural History” by Professor Catrin Rutland (2021) Amazon.com;

Early Domesticated Animals

The domestication of plants and animals took place around the same time. Hunter-gatherers and village horticulturists kept pets so they knew how to take care of animals. The domestication of animals took place when animals were raised as a source of food and labor. Grains were raised with the intent of feeding people and animals.

Some animals were domesticated so long ago that they have evolved as separate species. The process, some theorize, was as much accidental as intentional. With cats, for example, the anthropologist Richard Bullet suggests, the ancestors of cats were attracted to human settlements because they kept stores of grain that attracted mice they could fed on. Humans in turn tolerated the cats because they ate mice that fed on their grain and otherwise were not threatening.

Bullet as also theorized that horses, cattle and sheep were initially not domesticated for food but were domesticated for religious sacrifices. He argues it was more easy to hunt these animals than herd them and humans would have not gone through the trouble of keeping them unless they served some other purpose. He speculated that perhaps that unruly animals were sacrificed first to avoid trouble leaving more docile animals to mate and their offspring became increasingly tame.

See Separate Articles: EARLY DOMESTICATED ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

Donkeys in Ancient Egypt

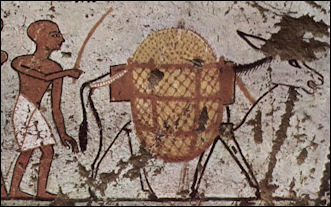

Donkeys appeared in Egypt in the third millennium before Christ and are pictured on old Kingdom engravings dated to 2700 B.C., carrying people and loads in villages and urban areas. Donkeys were among the first members of the horse family to be domesticated. They are believed to have been domesticated from wild asses, or onagers, from Arabia and North Africa about 6,000 years ago.

Donkeys were widely used as beasts of burden and a means of travel. The donkey was well suited for the particular conditions found in Egypt; it is an indefatigable and, in good examples, also a swift animal, and is able to go everywhere. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Yet it seems to have been considered scarcely proper to use it for riding; there are few representations of people riding on a donkey, though there is an unmistakable donkey-saddle in the Berlin Museum, which vouches for this practice, at any rate during the New Kingdom. Nevertheless there was no impropriety in a man of rank traveling in the country in a kind of seat fastened to the backs of two donkeys, as we see by a pleasing representation of the time of the Old Kingdom. In an image called “Journey in a Donkey Sedan-chair” two runners accompany their master, one in front to clear the way for him, the other to fan him and to drive the donkey. In a letter from the New Kingdom there is the mention of the shoeing of a donkey with bronze.

See Separate Article: DONKEYS: THEIR HISTORY, USES AND BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com ONAGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com ; Also See Donkeys and Threshing Under FARMERS, CROPS AND FARM WORK IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Sheep and Goats in Ancient Egypt

Robert Partridge of the BBC wrote: “Sheep were kept for their meat, milk, skins and wool, and flocks of sheep were used to trample newly sown seed into the ground. Rams, seen as a symbol of fertility, were identified with various gods, notably Khnum, a creator god, and Amun, the great god of the city of Thebes. Ram-headed sphinxes flank the entrance to the temple of Amun at Thebes. The bodies of some rams were mummified and equipped with gilded masks and even jewellery. [Source: Robert Partridge, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Famous reference to wool and sheep from the ancient world include Jason's quest for the Golden Fleece, Ulysses escaping from the Cyclops by clinging onto the underbelly of a ram, and Penelope's nightly unraveling of her weaving to keep suitors away until Ulysses returned. Salome's veils may have been wool and Cleopatra most likely used a wool carpet to smuggle herself in to see Caesar.╤

Famous reference to wool and sheep from the ancient world include Jason's quest for the Golden Fleece, Ulysses escaping from the Cyclops by clinging onto the underbelly of a ram, and Penelope's nightly unraveling of her weaving to keep suitors away until Ulysses returned. Salome's veils may have been wool and Cleopatra most likely used a wool carpet to smuggle herself in to see Caesar.╤

Goats have been around a long time. Mesopotamians wrote poems about goats, depicted them in golden sculptures, worshiped them as gods and made the goat-god Capricorn into a Zodiac sign. Goats have been taken all over the world to trade as sources of meat, wool and milk. Goats are mentioned in the Bible as well as in Buddhist, Confucian and Zoroastrian texts. In Greek myths, the gods were nursed on goats milk.

Fifth Century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: Now the reason why those of the Egyptians whom I have mentioned do not sacrifice goats, female or male, is this: — the Mendesians count Pan to be one of the eight gods (now these eight gods they say came into being before the twelve gods), and the painters and image-makers represent in painting and in sculpture the figure of Pan, just as the Hellenes do, with goat's face and legs, not supposing him to be really like this but to resemble the other gods; the cause however why they represent him in this form I prefer not to say. The Mendesians then reverence all goats and the males more than the females (and the goatherds too have greater honour than other herdsmen), but of the goats one especially is reverenced, and when he dies there is great mourning in all the Mendesian district: and both the goat and Pan are called in the Egyptian tongue Mendes. Moreover in my lifetime there happened in that district this marvel, that is to say a he-goat had intercourse with a woman publicly, and this was so done that all men might have evidence of it. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A.D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

See Separate Articles: SHEEP: THEIR HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS AND DOLLY factsanddetails.com ; GOATS: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, MILK AND MEAT factsanddetails.com ; WOOL: HISTORY, TYPES, PROCESSING AND TRADE factsanddetails.com

Pigs in Ancient Egypt

The Egyptians kept pigs but not for food. They were used as scavengers and to root through soil to prepare it for planting. Swineherds were a distinct class. According to Herodotus they were the most reviled class in Egypt. They were forbidden from entering temples.

Pigs are believed to have been domesticated from boars 10,000 years ago in Turkey, a Muslim country that ironically frowns upon pork eating today. At a 10,000-year-old Turkish archeological site known as Hallan Cemi, scientists looking for evidence of early agriculture stumbled across of large cache of pig bones instead. The archaeologists reasoned the bones came from domesticated pigs, not wild ones, because most of the bones belonged to males over a year old. The females, they believe, were saved so they could produce more pigs.

Pigs were originally tuber-eating forest and swamp creatures. They had difficulty living in the deserts of the Middle East because they don't sweat and therefore can't cool themselves. When pigs were first domesticated there were vast forest areas in what is now Turkey and the Middle East. There was enough water and shade to support small number of pigs, but as population in the Middle East grew, deforestation degraded the environments best suited for the animals.

In the fifth and fourth millennia B.C. in Mesopotamia, 30 percent of bones excavated in Tell Asmar (2800-2700 BC) belonged to pigs. Pork was eaten in Ur in pre-Dynastic times. After 2400 B.C. it had become taboo. In Egypt, pigs were eaten, but there was prejudice against pork associated with Seth, the God of Evil.

See Separate Articles: PIGS: CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, PRODUCERS AND PORK-EATING CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com See Myth of Horus Under MEAT AND CHEESE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

See Separate Article: SACRIFICES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: PIGS, BULLS AND POSSIBLY HUMANS africame.factsanddetails.com

Birds, Chickens and Pigeons in Ancient Egypt

ducksChickens were raised in Egypt and China for meat and eggs by 1400 B.C. The Egyptians hatched eggs by placing them in ovens. Pigeons were domesticated by the Egyptians and Romans, many were kept as sources source of meat that were available throughout the year. Their ancestors, rock pigeon, lived on cliffs and in caves on the coast. Domesticated pigeons were provided with tall towers with ledges for them to roost that simulated their coastal homes.

The Egyptians mainly provided themselves with birds from the wild. The bird-catchers caught geese and other birds in the marshes in their large nets and traps, they were then reared and fattened. The Egyptians, at any rate in the early period, had no tame birds. Why should they take the trouble to breed them when the bird-catcher could get them with so little trouble? [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

An immense number of European birds of passage “inundate Egypt with their cloud-like swarms," and winter every year in the marshes with the numberless indigenous water-birds. For this reason the birds of an ancient Egyptian property present a more brilliant appearance than would be possible were the domestic birds represented alone. We find, in the first place, flocks of geese and ducks of various kinds, each of which bears its own special name. In addition, there were all manner of swans, doves, and cranes; the Egyptians evidently took a special delight in representing the different species of the latter; these birds also seem to be always fighting with each other, thus forming a contrast to the peaceful geese and ducks.

As I had already remarked, the birds were fattened in the same way as the cattle; the fattening bolus was pushed down the throat of the goose in spite of its struggles. '' This fattening diet was given in addition to the ordinary feeding; we could scarcely believe, for instance (as in fact it was represented), that “the geese and doves hasten to the feeding," on the herdsman clapping his hands, if he had nothing to offer them but those uncomfortable fattening balls of paste. A picture of the time of the Old Kingdom shows us also that care was taken in “giving drink to the cranes. "

Cattle in Ancient Egypt

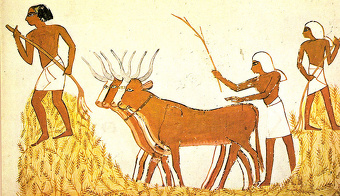

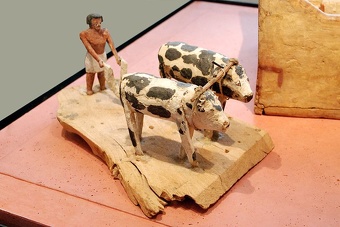

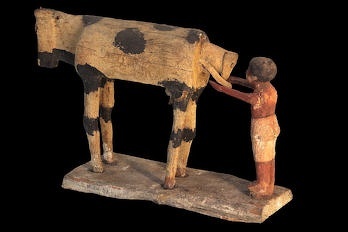

Cattle-breeding was widely practiced in Ancient Egypt. There are many pictures of cattle, especially from of the Old Kingdom. Egyptians talked to their cattle as we talk to our dogs; they gave them names and decked out the finest with colored cloths and pretty fringes; they represented their cattle in all positions with an observation both true and affectionate, showing plainly how dearly they valued them. Bulls were treated with reverence by Egyptians (black bulls in particular were given harems and palaces because they were believed to be related to the bull-god Apis).

Robert Partridge of the BBC wrote: “Cattle were reared in great numbers in Egypt, and they were also imported, often as spoils of war. They were a prized possession, providing meat, milk, leather and horn. Their dung was burnt as fuel. Their leather was used to make thongs, sandals, chair seats and shields. Tomb scenes and tomb models often show the tomb owners inspecting their herds of cattle, and individual beasts were sometimes given pet names.” [Source: Robert Partridge, BBC, February 17, 2011]

The ancient Egyptians took care that the food for the cattle was plentiful, though perhaps not quite in the way described in the Story of the New Kingdom: “His cattle said to him: ' There and there the herbs were good,' and he heard what they said and drove them to the place of good herbs, and the cattle which he kept throve excellently and calved very often. " As a matter of fact, they had a much more prosaic method of fattening their cattle, namely, with the dough of bread. Judging from the pictures in the tombs, this method must had been in common use during the Old Kingdom. We continually see the herdsmen “beating the dough," and making it into rolls; they then squat down before the ruminating cattle and push the dough from the side into their mouths, admonishing them to “eat then. " A good herdsman had also to see after the drink of his cattle; he sets a great earthen vessel before them, patting them in a friendly way to encourage them to drink. He had, of course, to go more sternly to work when he wanted to milk the “mothers of the calves," or as we should say, the milch cows. He had to tie their feet together, or to make one of his comrades hold their front legs firmh'; the calves who disturbed his work had also to be tied up to pegs.'' [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

See Separate Articles: SACRIFICES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: PIGS, BULLS AND POSSIBLY HUMANS africame.factsanddetails.com ; FIRST CATTLE AND COW DOMESTICATION factsanddetails.com ; CATTLE: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND MEAT factsanddetails.com

Types of Cattle in Ancient Egypt

According to the pictures and the skulls that we possess, the species of cattle which the ancient Egyptians kept were most similar to present-day they cattle. These animals had a “forehead very receding, the little projection of the edge of the socket of the eye, the flatness and straightness of the whole profile strongly marked. " The hump on ancient Egyptian cattle was less pronounced than those found on modern zebus. This was also often the case with zebu-like cattle found in Africa. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The Egyptians developed several species and varieties from the zebu by breeding; these differed not only in appearance, but their flesh also varied in goodness. The most important species during the Old Kingdom was the long-horned; They animals had unusually long horns, which as a rule were bent in the lyre form, more rarely in that of the crescent. Further, they possessed “a dignified neck like the bison . . . a somewhat high frame, massive muzzle, and a fold of skin on the belly." They were generally pure white, or white with large red or black spots, or they might be light yellow or brown; in one of the pictures we see a rather uncanny-looking animal of a deep black color, with red belly and ankles. The connoisseur recognised several varieties of this long-horned people; the common 'ena was distinguished from the rarer ncgt though to our uninitiated eyes there was no recognisable difference between the representations of the two varieties.

In the pictures of the Old Kingdom, animals with short horns were represented more rarely than the long-horned, though the former appear frequently in later times. Whether they were rarer in the earlier period, or whether in their reliefs the Egyptians preferred to represent the longhorned species, because they looked more picturesque and imposing, we cannot decide.

In the Old Kingdom reliefs there were also representations of animals which apparently remained hornless all through the different stages of their life. These may be regarded as a third species. " They seem to had been valued as fancy cattle, for we never find them employed in ploughing or threshing; the peasants liked to deck them out in bright cloths and bring them as a present to their master. At the same time they cannot had been very rare, for on the property of KhafRaonch there were said to be 835 long-horned animals, and no less than 220 of the hornless species.

In addition to the principal breed of cows — the old long-horned people which still exists in the Nile valley, there appears to had been another variety, represented in illustrations, which seems to had come to the fore for a time during the New Kingdom. These animals, as we see, had rather short horns which grow widely apart, and had lost their old lyre shape; in some instances the hump was strongly developed, and the color of the skin was often speckled. It may be that this species originated from foreign parts, for when Egypt ruled over Nubia, and for a time over Syria also, cattle were often brought into the Nile valley either as tribute or as spoil from these countries. Thus the Theban Amun received from Thutmose III. a milch-cow from Palestine, and three cows from Nubia;" and under Ramses III., amongst the charges on his Syrian property, there were included seventeen cattle. ' Bulls from the land of the Hittites and cows from 'Ersa were valued especially, highly, as well as bullocks “from the West “and certain calves “from the South." There was one representation of Nubian cattle, and amongst them two remarkable short-horned animals which, according to the barbarian custom, were drawing the carriage of an Ethiopian princess.

Cattle Breeding in Ancient Egypt

The care with which the different breeds were kept apart in the pictures shows that, even during the Old Kingdom, the Egyptians had already emerged from the primitive stage of cattle-breeding. They were no longer content to lead the animals to their pasture and in other respects to leave them to themselves; on the contrary, they watched over every phase of their life. Special bulls were kept for breeding purposes, and the herdsmen understood how to assist the cows when calving. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The Egyptians were not content with the different varieties of the original breed, which were due to their skill in breeding; they adopted also an artificial method in order to give the animals a peculiar appearance. They had a method of bending one horn of the bull downwards, and this gave the animal a most fantastic appearance. ' This result was probably obtained by the same process which was still employed in the east of the Sudan; the horn substance was shaved off as far as the root on the side to which the horn was to bend; as it healed, the horn would bend towards the side intended, and finally the bending was further assisted b\hot irons.

The description of cattle-breeding, which I had sketched out above, is founded on the reliefs of the Old and the Middle Kingdom, where this theme was treated with evident predilection. What we know of the subject of later date was comparatively little; other matters seem to had been more interesting to the great men of the New Kingdom. Cattle-breeding seems however to had forfeited none of its old importance in the country, for we still hear of enormous numbers of cattle. The Egyptian temples alone, during the space of thirty-one years, were said to had received 514,968 head of cattle and 680,714 geese; this denotes, as far as I could judge, that live-stock were kept in far greater numbers than at the present day.

Horses in Ancient Egypt

Robert Partridge of the BBC wrote: “The horse, along with the chariot, was introduced into Egypt relatively late in its history, around 1500 B.C. Chariots were pulled by two horses, and were used not only in battle, but also for ceremonial occasions and for hunting. Horses were bred in Egypt, and initially their rarity and novelty meant that they were a status symbol, owned only by wealthy and influential people. They were well looked after, and were given individual names, splendid stables and the best fodder. [Source: Robert Partridge, BBC, February 17, 2011]

As a rule stallions were used rather than mares; the color of the animals was generally brown — in a few instances however we meet with a team of fine white horses. As far as I know geldings were not in use at this period. Those who required quiet animals preferred to employ mules; in a pretty Theban tomb-picture we see the latter animals drawing the carriage of a gentleman who is inspecting his fields; they are so easy to manage that a boy is acting as coachman. ' [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The horse was also used for riding in Egypt, but as with other nations of antiquity, riding was quite a secondary matter. We have no representations of Egyptians on horseback, and were it not for a few literary allusions, we should not know that the subjects of the Pharaoh understood at all how to ride. Thus in one place we hear of the “officers (?) who are on horseback “pursuing the vanquished enemies, and one of the didactic letters speaks of “every one who mounts horses. " “In one story we read that the queen accompanied the Pharaoh on horseback, and the satirical writer mentioned above says that he received the letter from his opponent when “seated on horseback. " At the same time we must repeat that the use of horses for riding was quite a secondary matter: the chief purpose for which they were used was driving.

See Separate Articles: HORSES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND BREEDS factsanddetails.com ; PREHISTORIC HORSES AND HORSE EVOLUTION factsanddetails.com EARLY HORSE DOMESTICATION: BOTAI CULTURE, EVIDENCE AND DOUBTS factsanddetails.com

Camels in Ancient Egypt

Dromedary camels — one-humped camels as seen in the Middle East today — were first domesticated in Arabia about 5,500 years ago but disn’t show up in Ancient Egypt until well after that. The camel does not appear in any inscription or picture before the Greek period,"' and even under Ramses III. the donkey is still expressly mentioned as the beast of burden of the desert' [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

According to University College London: They are sporadically attested in the Early Dynastic Period, but it was not regularly used until much later. Foreign conquerors (Assyrians, Persians, Alexander the Great) brought the camel on a greater scale to Egypt. Certainly in the Ptolemaic Period, and perhaps already under the Persians (525-343 BC), the camel (also the two-humped camel, camelus bactrianus) was used as main transport animal for the desert.

Camels were not native to Egypt. They likely began to appear in the region in the context of trade and transport across deserts. By the time of the Ptolemaic period (332-30 BC), camels were used in Egypt for various purposes, including transport and trade, particularly in the desert regions. However, their primary use in Egypt became more prominent in later periods, especially during the Roman Empire and beyond, when they were integral to long-distance trade routes.

See Separate Articles: CAMELS: TYPES, HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, HUMPS, WATER, FEEDING factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024