Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex) / Culture, Science, Animals and Nature / Economics

HUNTING: THE ROYAL SPORT OF ANCIENT EGYPT

The Egyptians speared hippos and hunted animals such as ibex and antelope in a region they called “ deshret” . Hunting and battle scenes were commonly drawn. Some depict dogs biting antelopes, ostriches squawking in terror and horses, hyenas and hartebeests on the run. In background hieroglyphic images sometimes explain what is going on. The ancient Egyptians used boomerangs. Forth millennium B.C. drawings show hounds hunting with men and driving game into nets. Ducks were hunted with throw sticks by men hiding in the reeds

Hunters made their way through the swamps on boats made of reeds, and hunted there with throwsticks. Their knives, in part at least, as well as the tips of their arrows, were made of flint. The monuments of the Old Kingdom feature images of bird-snarers. Their clothing of rush-mats, and the manner in which they wear their hair and their beard, make them appear different. These dwellers in the swamps may possibly belong to a different people from the native Egyptians. We know that the northwest of the Delta was inhabited by Libyans. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The Egyptians were fond of taking antelopes alive, not in order to stock their parks with them, but to fatten them with their cattle. They seem to have caught the ibex of the hills by hand; in the desert however they employed the lasso, a long rope with a ball at the end, which when thrown at an object wound itself round it. " A skilled sportsman would throw the lasso so that the rope wound round the legs and body of the animal, while the end twisted itself in the horns. A powerful jerk from the huntsman then sufficed to throw the animal helplessly on the ground. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

We might almost surmise that the Egyptians felt that scorn for shooting weapons common to so many nations; at any rate representations of sport with bow and arrow are much rarer than those of hunting. - Even when shooting they employed dogs to start the game, and possibly beaters armed with sticks to drive the animals towards the sportsmen. With the powerful bow and the arrows a yard long it was quite possible to kill even lions.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Arts, Leisure, and Sport in Ancient Egypt” by Don Nardo (2005), Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Food and Festivals” by Stewart Ross (2001) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Famine and Feast in Ancient Egypt” by Ellen Morris (2023) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

“Beni Hassan: Art and Daily Life in an Egyptian Province” by Naguib Kanawati and Alexandra Woods (2011) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

“The Ancient Egyptians and the Natural World: Flora, Fauna, and Science” by Prof. Dr. Salima Ikram, Jessica Kaiser, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt's Wildlife: An AUC Press Nature Foldout”

by Dominique Navarro and Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Wildlife: Past and Present” by Dominique Navarro (2016)

Amazon.com;

“A Guide to Extinct Animals of Ancient Egypt” by Anthony Romilio (2021) Amazon.com;

:A Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Egypt” by Sherif Bahaa El Din (2006) Amazon.com;

“A Field Guide to the Mammals of Egypt” by Richard Hoath (2009) Amazon.com;

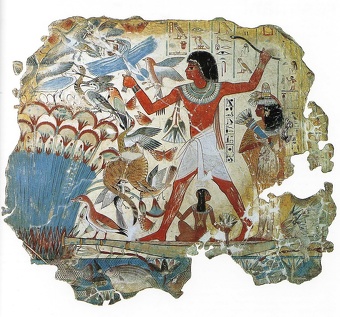

Painting of Hunting in Ancient Egypt

According to a 1955 Sports Illustrated article “Egyptian artists, through the many centuries of great empire under the Pharaohs in the Nile Valley, created indisputable masterpieces, not a few of which depicted sports. Many of them suffered the depredations of time and man and no longer remain to be admired. In time they cover several eras. The little painting, Birds in an Acacia Tree, dates from about 1900 B.C. The painting of the youthful King Tutankhamun was done about 3,300 years ago. [Source: Sports Illustrated, September 26, 1955]

The fine hunting and fishing scenes are of an earlier period. Yet in each, one finds the same magnificent colors, the flawless sense of composition and the decorative richness of stylization. These are paintings of genre type, biographical in nature. They tell of pleasures enjoyed in earthly life, to be continued in life beyond the grave. The animals, birds and fish are among the classic wildlife paintings of all time.

“1) "Tutankhamun Hunting Lions" a decoration from the lid of a box found in the young Pharaoh's tomb, is a scene of magnificence and violence. Papyrus thickets on the banks of the Nile were fine hunting and fishing grounds for elite of Thebes, who made a day of sport into a family outing 2) "Fishing and Fowling in the Marshes" shows the use of throwing stick and spear. At left the hunter holds live birds as decoys while a trained cat flushes the birds. 3) "Hunting Wild Fowl in the Marshes" again illustrates the throwing stick, the live decoys and the trained cat. The sportsman, accompanied by his wife and daughter, has nonchalantly draped lotus flowers over his shoulder, while his little girl keeps him from falling off the reed boat by hanging onto his leg.”

Hunting in the Marshes of the Nile

Many of ancient Egypt’s marshes and tropical forests were transformed into arable land but at the same time old river beds remained; stretches of marsh and half-stagnant water remained. Marshes with papyrus reeds, offered shelter to the hippopotamus, the crocodile, and to numberless water birds. This was the happy hunting-ground of the great lords of ancient Egypt, the oft-mentioned “backwaters," the “bird tanks of pleasure. " The greatest delight perhaps that the Egyptians knew was to row in a light boat between the beautiful waving tufts of the papyrus reeds, to pick the lotus flowers, to start the wild birds and then knock them over with the throw-stick, to spear the great fish of the Nile and even the hippopotamus, with the harpoon. Pictures of all periods exist representing these expeditions, and we have but to glance at them in order to realise how much the Egyptians loved these wild districts, and how much poetry they found in them. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

We see how the great papyrus shrubs lift up their beautiful heads high above the height of man, while “their roots are bathed “as a botanist says, “in the lukewarm water, and their feather tufts wave on their slender stalks. " With the help of other reeds and water plants they form an impenetrable thicket — a floating forest. Above, there swarm, as now in the Delta, a cloud of many thousand marsh-birds. We see in our picture that it is the close of the breeding season; a few birds are still sitting on their nests, which are built on the papyrus reeds and swayed by the wind, while most of the others are flying about seeking food for their young. One bird is chasing the great butterflies which are fluttering round the tops of the papyrus reeds; another with a long pointed beak darts down upon a flower in which he has discovered a cockchafer. In the meantime danger threatens the young ones; small animals of prey, such as the weasel and the ichneumon, have penetrated into the thicket, and are dexterously climbing up the stems of the reeds. The startled parents hasten back, and seek to scare away the thieves with their cries and the flapping of their wings.

Meanwhile in a light boat formed of papyrus reeds bound together the Egyptian sportsman makes his way over the expanse of water in this marsh; he is often accompanied by his wife and children, who gather the lotus flowers and hold the birds he has killed. Noiselessly the bark glides along by the thicket, so close to it that the children can put their hands into it in their play. The sportsman stands upright in the boat and swings his throw-stick in his right hand; with a powerful throw it whizzes through the air, and one of the birds falls into the water, hit on its neck. This throw-stick is a simple but powerful weapon. It is most remarkable that in many of the pictures of the New Kingdom a tame cat accompanies the sportsman and brings him the fallen birds out of the thicket into the boat.

Desert Hunting in Ancient Egypt

The Libyan deserts and the Arabian mountains still offer great opportunities for sport, and in old times this was yet more the case, for many animals which formerly inhabited these regions are only met with now in the Sudan. Flocks of ibex climbed about the mountains, herds of gazelles sported about the sand dunes; there were also antelopes and animals of the cow kind. The hyaena howled and the jackal and fox prowled about the mountains on the edge of the desert; there were also numerous hares and hedgehogs, ichneumons, civet cats, and other small animals. There was big game too for the lovers of an exciting hunt; they could follow the leopard or the lion. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The Egyptians of all ages loved desert hunting. We know that the kings of the Old Kingdom had their own “master of the hunt," who was also district chief of the desert; “and as regards the Pharaohs of the New Kingdom, we often read of their hunting in person. Thutmose IV., accompanied only by two lions, used to hunt in the neighbourhood of Memphis, and we read of his son Amenhotep III., that during the first ten years of his reign he killed with his own hand "10 savage lions. '"

Packs of dogs were usually employed in desert hunting; they were allowed to worry and to kill the game. The hunting dog was the great greyhound with pointed upright ears and curly tail; this dog is still in use for the same purpose on the steppes of the Sudan. It is a favorite subject in Egyptian pictures to show how cleverly they would bury their pointed teeth in the neck or in the back paws of the antelopes. These graceful dogs also ventured to attack the larger beasts of prey. A picture of the time of the Old Kingdom represents a huntsman who, having led an ox to a hilly point in the desert, lies in wait himself in the background with two greyhounds. The ox, finding himself abandoned, bellows in terror; this entices a great lion to the spot, and the huntsman watches in breathless suspense, ready in a moment to slip the leash from the dogs and let them fall on the lion, while the king of animals springs on the head of the terrified ox.

Netting in Ancient Egypt

André J. Veldmeijer of the Netherlands Flemish Institute in Cairo wrote: “The spinning of flax thread for the production of textiles is well known and described in detail by various authors. Vogelsang-Eastwood suggests that first the flax fibers were loosely twisted and then spun into the final thread in a second stage. Usually, flax fibers were wetted before being spun, after which the thread could be plied, used in the manufacture of textiles, or, less commonly, made into a net, most of the flax netting having been made of plied string.” [Source: André J. Veldmeijer, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Egyptian netting was most commonly used in fishing and for carrying/holding objects, such as jars and beakers. Fishing and carrier nettings were usually made with different knots. Fishing nets were exclusively made with mesh knots, whereas carrier nets were made with overhand knots, in addition to mesh knots. The carrier net was one of several included in the intact burial of a woman and child found by Petrie in 1908 at Dra Abu el Naga; these were constructed with half knots and bore strong parallels to the Kerma netting described by Reisner . Knotless netting, a technique used for various objects ranging from carrier nets to sieves, is reported. “Sprang” netting (a particularly flexible form of netting) does not occur in Egypt before the Roman Period.

“Wendrich has described in detail the production of netting made with mesh knots. First, a row of loops was knotted to a border string. A subsequent row of loops was then knotted to the first, and so on, using a netting needle. It should be noted that Wendrich’s description focuses on mesh- knot netting constructed of knots having the same orientation per row, each row alternating in direction. Veldmeijer suggests alternative production processes for netting with non- alternating rows or with variously oriented knots. The knotting of reef-knot netting differed slightly: although the net was constructed from either left to right or right to left, the knots were oriented horizontally rather then vertically as they were in mesh- knot netting. Alternatively, reef-knot nets may also have been manufactured by pulling hitches, which involved a netting needle. Finally, handles, weights, and floaters were tied to the net when appropriate.

“The production of fishing nets was depicted in Egypt as early as the Old Kingdom. Well- known examples include the depictions of net makers in the Middle Kingdom tombs of Beni Hassan. The essential task of fishing-net repair was also depicted in some Old Kingdom tombs. An example from the New Kingdom can be found in the tomb of Paheri.”

Bird Netting in Ancient Egypt

The great numbers of waterbirds required for Egyptian housekeeping were caught in a less delightful but much more effective manner; a large bird-net was used, which we often see represented in the tombs. The net was spread on a small expanse of water surrounded by a low growth of reeds. Judging from the representations, it was often 10 to 12 feet long and about five feet wide. It was made of netted string and had eight corners. " When spread, the sides were drawn well back and hidden under water plants; in order to draw it up, a rope which ran along the net and was fastened behind to a clod of earth, had to be pulled hard. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

How they enticed the birds into the net, whether by bait or by a decoy bird, I can scarcely tell, for the favorite time for representation on our monuments is always the moment when the net is being drawn together. Three or four fellows who have thrown off every useless bit of clothing, hold the long rope, and wait in breathless attention for the command to draw the net together. In the meantime the master has slipped through the bushes close to the net, and has seen and heard that the birds arc caught in the snare. He dares not call out to his men for fear of scaring the birds, so he gives them the signal by waving a strip of linen over his head. The workmen then pull the rope with might and main, they pull till they literally lie on the ground. Their cffcjrts arc rewarded, for the net is full of birds, thirty or forty great water-birds being caught in it; most as we see are geese, but an unfortunate pelican has also wandered in. The latter has little chance of mercy from the bird-catcher, who now gets into the net and seizes the birds one by one by their wings, and hands them to his men; of these the first appears to be breaking the wings, while the others place them in large four-cornered cages, first sorting them, for the Egyptians loved order; “those in the box? “asks one of another meanwhile.

The cages are then carried home on hand-barrows, where the fattest geese are proudly exhibited to the master; one of the species ser, though unusually fat, is far surpassed by another of the species terp. From the marshes on this occasion they also bring lotus flowers for wreaths and for the decoration of the house — a present is also brought in from the net for the young master; a gay hoopoe, which he almost squeezes to death with the cruel love of a child.

As we have already remarked, this manner of bird-catching was not mere sport in the early ages of the 5th and 6th dynasties; at that time there was a special official on many estates, the “chief bird-catcher," and the people also thus obtained their favorite national dish — roast goose. They evidently pursued this sport regularly, and indeed a picture of the time of the New Kingdom shows us how they salted down the remaining birds in large jars.

When however, instead of prosaic geese, they wanted to catch the pretty birds of passage, the “birds of Arabia who flutter over Egypt smelling of myrrh," they used traps baited with worms. " It was a favorite pastime even for ladies “to sit in the fields all day long, waiting for the moment when at last they should hear the “wailing cry of the beautiful bird smelling of myrrh. "

Fishing in Ancient Egypt

fishing The Egyptians ate a lot of fish. They ate all the varieties that were found in the Nile and many from the Mediterranean. Agricultural crops were not the mainstay of the ancient Egyptian diet as the Nile supplied a constant influx of fish which could be caught year around. Archaeologists have found evidence of fish processing operation, where fish were cleaned, salted and smoked. Fish was also made into sauce.

The peaceful wellstocked waters of the Nile invited the inhabitants of the country to this easy sport. The most basic manner of fishing — with the spear, was only pursued later as a sport by the wealthy. For this purpose the Egyptians used a thin spear nearly three yards long, in front of which two long barbed points were fastened. The most skilful speared two fish at once, one with each point. Angling was also considered a delightful recreation for gentlemen; we see them seated on chairs and rugs fishing in the artificial lakes in their gardens. "' [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The common fishermen also did not despise line fishing. As a rule however the latter fished in a more effective manner, with the “bow-net" or with the “drag-net.'' We see how the latter is set upright in the water, quite in the modern style, with corks fastened on the upper edge and weights on the lower. Seven or eight fishermen then drag it through the water to the land. The catch is a good one, about thirty great fish are caught at one haul, and lie struggling on the bank. Many are so heavy that a man can only carry one at a time; a string is put through the gills of the others, and they are carried in a row on a stick to the fish dealers.

These dealers are seated on low stones before a sort of table, cleaning out the inside of the fish and cutting them open so as to dry them better. The fish were then hung upon strings in the sun to dry thoroughly; when the fishermen were far from home, they began this work on board their boats. These dried fish were a great feature in Egyptian housekeeping; no larder was without them, and they formed the chief food of the lower orders. They were the cheapest food of the land; much cheaper than corn, of which the country was also very productive. The heartfelt wish of the poorer folk was that the price of grain might be as low as that of fish. Fish was also a favorite dish with the upper classes; and the epicure knew each variety, and in which water the most dainty were to be caught. '' It was therefore a most foolish invention of later Egyptian theology to declare that fish were unclean to the orthodox and so much to be avoided, that a true believer might have no fellowship with those who ate fish. '

Herodotus on Fish in Ancient Egypt

Fifth Century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: Fish which swim in shoals are not much produced in the rivers, but are bred in the lakes, and they do as follows: — When there comes upon them the desire to breed, they swim out in shoals towards the sea; and the males lead the way shedding forth their milt as they go, while the females, coming after and swallowing it up, from it become impregnated: and when they have become full of young in the sea they swim up back again, each shoal to its own haunts. The same however no longer lead the way as before, but the lead comes now to the females, and they leading the way in shoals do just as the males did, that is to say they shed forth their eggs by a few grains at a time, and the males coming after swallow them up. Now these grains are fish, and from the grains which survive and are not swallowed, the fish grow which afterwards are bred up. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A.D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

Now those of the fish which are caught as they swim out towards the sea are found to be rubbed on the left side of the head, but those which are caught as they swim up again are rubbed on the right side. This happens to them because as they swim down to the sea they keep close to the land on the left side of the river, and again as they swim up they keep to the same side, approaching and touching the bank as much as they can, for fear doubtless of straying from their course by reason of the stream. When the Nile begins to swell, the hollow places of the land and the depressions by the side of the river first begin to fill, as the water soaks through from the river, and so soon as they become full of water, at once they are all filled with little fishes; and whence these are in all likelihood produced, I think that I perceive. In the preceding year, when the Nile goes down, the fish first lay eggs in the mud and then retire with the last of the retreating waters; and when the time comes round again, and the water once more comes over the land, from these eggs forthwith are produced the fishes of which I speak.

Thus it is as regards the fish. And for anointing those of the Egyptians who dwell in the fens use oil from the castor-berry, which oil the Egyptians call kiki, and thus they do: — they sow along the banks of the rivers and pools these plants, which in a wild form grow of themselves in the land of the Greeks; these are sown in Egypt and produce berries in great quantity but of an evil smell; and when they have gathered these some cut them up and press the oil from them, others again roast them first and then boil them down and collect that which runs away from them. The oil is fat and not less suitable for burning than olive-oil, but it gives forth a disagreeable smell. Against the gnats, which are very abundant, they have contrived as follows: — those who dwell above the fen-land are helped by the towers, to which they ascend when they go to rest; for the gnats by reason of the winds are not able to fly up high: but those who dwell in the fenland have contrived another way instead of the towers, and this it is: — every man of them has got a casting net, with which by day he catches fish, but in the night he uses it for this purpose, that is to say he puts the casting-net round about the bed in which he sleeps, and then creeps in under it and goes to sleep: and the gnats, if he sleeps rolled up in a garment or a linen sheet, bite through these, but through the net they do not even attempt to bite.

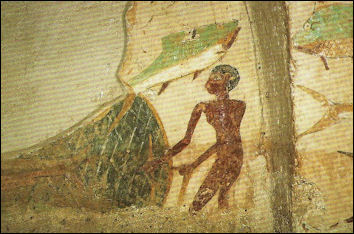

Artwork Depicting Fishing in Ancient Egypt

fishing

Reliefs show fishermen using nets and harpoons to catch fish in shallow water. At the Temple of Hatshepsut there is a scene of birds being captured in nets.

André J. Veldmeijer of the Netherlands Flemish Institute in Cairo wrote: “Pictorial evidence shows that fishing boats were generally small, able to be operated by one to five persons. Vessels might be rafts made of papyrus bundles (e.g., as seen in the papyrus models Y from the Middle Kingdom tomb of Mekhet-Ra) or made of wood (excellent illustration in the Ramesside tomb of Ipy). Many illustrations of fishing from boats show fishermen using various types of nets, sometimes (as in the two Mekhet-Ra papyrus boat models) with two craft working together. Other methods used from boats or rafts were spearing and line-fishing. Depictions of fishing are especially common in the Old Kingdom, but can be found in the Middle and New Kingdoms as well; documentary evidence forcommercial fishing continues on into the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, when there is at least some evidence for women involved in the occupation.[Source: André J. Veldmeijer, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

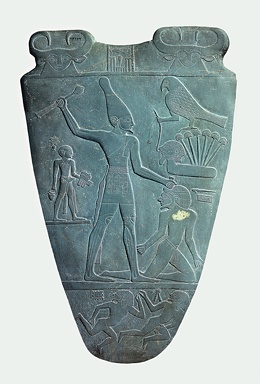

Elisa Castel wrote in National Geographic History: Many species of catfish live in the Nile. The one on the Narmer Palette (See Below) has been identified as belonging to the genus Heterobranchus. Another type of catfish, Malapterurus electricus, the electric catfish, was, very literally, a source of shock and awe to Egyptians: Its maximum charge of 350 volts can stun prey and deter predators, and deliver a nonlethal but painful shock to humans. Its representation on Old Kingdom reliefs of fishermen are the world’s earliest known depictions of these creatures. [Source: Elisa Castel, National Geographic, February 18, 2022]

Ancient Egyptians Loved and Revered Catfish

Elisa Castel wrote in National Geographic History: Cobras, cats, and vultures are among the most popular animals depicted in ancient Egyptian art, but the humble catfish once dominated the iconography of the civilization by the Nile. Common to every continent except Antarctica, catfish are the most diverse group of fish on earth. The 2,000 to 3,000 species have some remarkable characteristics, so it is little wonder they attracted the attention of the Egyptians, one of the most animal-conscious ancient cultures. [Source: Elisa Castel, National Geographic, February 18, 2022]

The ancient Egyptians had intimate knowledge of the several species of catfish that they observed among the rich life of the Nile River. Individual species are often clearly identifiable in Egyptian art and iconography. Egyptians attributed rich symbolic and mythological roles to the catfish. The upside-down catfish (Synodontis batensoda), for example, was imbued with symbolic importance. Its “flipped” orientation allows it to position its mouth close to the water’s surface, from where it appears to be swimming upside down. Belly-up on the surface, it appeared dead but was clearly alive, suggesting powers of regeneration.

Amulets of these creatures have been found throughout Old and Middle Kingdom sites in Egypt. These objects, it was believed, prevented drowning and were worn as necklaces or as hair ornaments. One gold pendant from the early second millennium B.C. is so naturalistic, it can be easily identified as the upside-down catfish.

Most of the animals associated with ancient Egypt were popular in the iconography of the New Kingdom (1539-1075 B.C.). The humble catfish was an icon thousands of years before then, during the Middle and Old Kingdoms and even the Predynastic Period. The catfish’s use as icon can be traced back to one of the oldest Egyptian artifacts, the Narmer Palette. Around 3000 B.C., Narmer is said to have led Upper Egypt in its conquest of Lower Egypt, thereby uniting the land and founding Egypt’s 1st dynasty. The palette depicts Narmer striking down an enemy with a mace; archaeologists know the victorious figure is Narmer because his name appears above him. It consists of two hieroglyphs: n’r (catfish) and mr (chisel).

In their names, pharaohs would attempt to align themselves with the kind of wild animals that would command respect. “The aggressive, controlling power of wild animals is a common theme in elite of the late Predynastic Period,” wrote Egyptologist Toby A. H. Wilkinson. “Within the belief-system of the late Predynastic Period, the catfish was evidently viewed as a symbol of domination and control, an ideal motif with which to associate the king. ”

Catfish were depicted on several significant tomb reliefs from this early period. One of the most well known is the mastaba of Ty, a 5th-dynasty noble whose tomb in Saqqara features several friezes of catfish and fishermen. Another example is the mastaba of Kagemni, vizier to the 6th-dynasty king Teti, at Saqqara. A relief in this tomb depicts a fishing scene in which men in papyrus skiffs appear to be pursuing fish of different types, including whiskery catfish.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024