Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

MEAT IN ANCIENT EGYPT

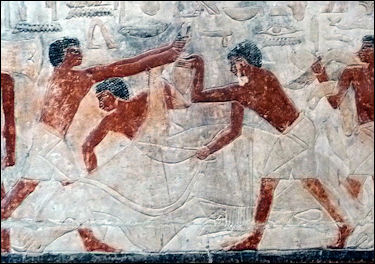

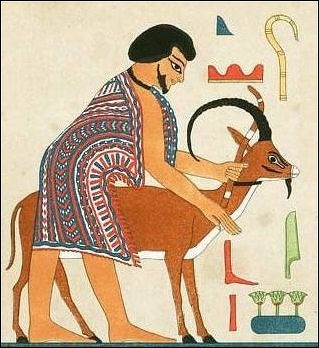

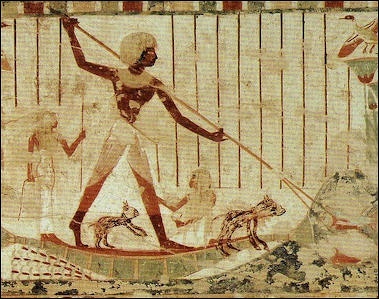

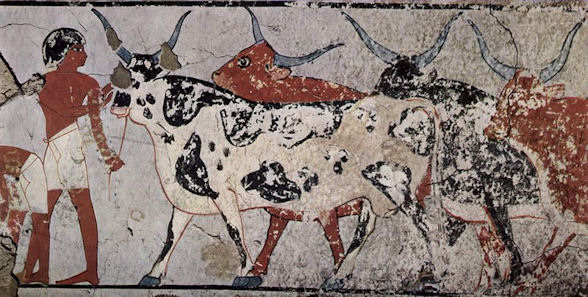

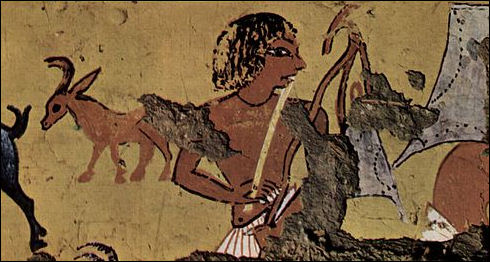

Ancient Egyptians ate the meat of cattle, sheep and goats. Lots of bones from slaughtered animals have been found. Hieroglyphics show ancient Egyptians hunting ducks, antelope and a variety of wild animals and using nets to catch birds as well as fish. There are even hieroglyphics describing slaves making foie gras.

Pigs were eaten for a time but there was a prejudice against pork associated with Seth, god of evil. Pigs are depicted at a New Kingdom (1055-1069 B.C.) temple in El Kab, south of Luxor. As time went on the ancient Egyptians distanced themselves from pigs, regarding them as unclean, and abstained from pork. Herodotus wrote “the pig is regarded among them as an unclean animal so much so that if a man passing accidently touches a pig, he instantly hurries to the river and plunges in with his clothes on.” Herodotus describes swineherds as an inbreed caste forbidden from setting foot in temples.

The Egyptians ate a lot of fish. They ate all the varieties that were found in the Nile and many from the Mediterranean. Archaeologists have found evidence e of fish processing operation, where fish were cleaned, salted and smoked. Fish was also made into sauce.

See Separate Article: LIVESTOCK AND DOMESTICATED ANIMALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Egyptian Food and Drink” by Hilary Wilson (2008) Amazon.com;

“Food Fit for Pharaohs: An Ancient Egyptian Cookbook”

by Michelle Berriedale-Johnson (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Pharaoh's Kitchen: Recipes from Ancient Egypt's Enduring Food Traditions”

by Magda Mehdawy (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptians’ Diet: The History of Eating and Drinking in Egypt by Charles River Editors (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Diet Reconstruction: The Elemental Analysis of Qubbet el Hawa Cemetery Bones” by Ghada Al-Khafif (2016) Amazon.com;

“Famine and Feast in Ancient Egypt” by Ellen Morris (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Food and Festivals” by Stewart Ross (2001) Amazon.com;

Nile Style: Egyptian Cuisine and Culture: Ancient Festivals, Significant Ceremonies, and Modern Celebrations” by Amy Riolo (2009) Amazon.com;

“Wine & Wine Offering In The Religion Of Ancient Egypt” by Mu-chou Poo (2013) Amazon.com;

“Wine in Ancient Egypt: A Cultural and Analytical Survey” by Maria Rose Guasch Jane (2008) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Meat, Status and Soup in Ancient Egypt

The kind of meat that people at was an indicator of their wealth and status. Veal and roast goose were regarded as treats that generally only the upper classes could enjoy. The poor ate goat and muttons if they ate any meat all.

Meat mummies of an afterlife feast displayed at the Egyptian Museum include ducks, pigeons, legs of beef, roast and an oxtail for soup. They were all dried in natron, wrapped in linen and packed in a picnic basket. “Whether or not you got it regularly in life didn’t matter because you got it for eternity,” one archeologist said.

Archaeology magazine reported: Archaeologists from Ancient Egypt Research Associates (AERA) unearthed sealings dating to the reign of the 4th Dynasty pharaoh Khafre (r. ca. 2520–2494 B.C.), along with chunks of painted plaster suggesting the material is from wealthy settlements. They also found a concentration of long, meat-bearing sheep and goat bones, many of whose ends had been snapped off. Two Egyptian archaeologists taking part in a field school at the site immediately recognized that the snapped-off ends were likely used to make gelatin soup, a cheap source of protein enjoyed to this day in Egypt. AERA director Mark Lehner suggests the meat from the bones was likely reserved for the area’s elites, while workers — quite possibly those who built Khafre’s pyramid, the second largest in Giza — were allotted the bone ends to make a protein-rich stew. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2018]

Meat and the Giza Pyramid Builders

cattle cutting Dr. Richard Redding and Brian V. Hunt wrote: “In an area of the world where people have traditionally reserved meat eating mostly for special occasions and feast-days, we have found evidence that the ancient state provisioned the pyramid city with enough cattle, sheep, and goat to feed thousands of people prime cuts of meat for more than a generation—even if they ate it every day. [Source: Dr. Richard Redding, Archaeozoologist, University of Michigan and Brian V. Hunt, Ancient Egypt Research Associates., ancientfoods.com, January 11, 2012 |]

“We have examined and identified over 175,000 bones and bone fragments from the excavations at the Giza pyramid settlement. The bones are from fish, reptiles, birds and mammals. About 10 percent have been identifiable to at least the level of the genus (a group of closely related species). Cattle and sheep dominate the fauna. We have found: 3,356 cattle fragments; 6,897 sheep and goat fragments; 536 pig fragments The ratio of individual sheep and goat to individual cattle is 5 to 1. |

“It might appear that sheep and goats were more common at Giza than cattle, and that sheep and goats were more important. But remember that an 18-month-old bull produces 10 to 12 times as much meat as an 18-month-old ram The ratio of sheep to goats at Giza is biased towards sheep. For the entire settlement site, the ratio of sheep to goat is 3 to 1. There is a low frequency of pig bones. |

“The cattle and sheep consumed at the settlement were young. 30 percent of the cattle died before 8 months, 50 percent before 16 months, and only 20 percent were older than 24 months. 90 percent of the sheep and goats survived 10 months, only 50 percent were older than 16 months, and only 10 percent older than 24 months. The cattle and sheep are predominately male. The ratio of male to female cattle is 6 to 1. The ratio of male to female sheep and goats is 11 to 1.” |

How Was So Much Meat Supplied for Giza Pyramid Builders

Dr. Richard Redding and Brian V. Hunt wrote: “What does this tell us about life at the pyramid settlement? The agrarian society of ancient Egypt was centered on crops and animals. The Egyptians’ colorful tomb paintings depict a rich agricultural life and we find evidence of this life in the archaeological remains of their settlements. The Egyptians could not catch fish, birds, and wild mammals in numbers adequate to support a large settlement like that at Giza. [Source: Dr. Richard Redding, Archaeozoologist, University of Michigan and Brian V. Hunt, Ancient Egypt Research Associates., ancientfoods.com, January 11, 2012 |]

livestock slaughter

“Feeding the pyramid builders required an increased production of domestic mammals: sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs. But there may have been inadequate space near Giza to support large herds of animals to feed the pyramid builders. Where did the supply of meat protein come from? Our models of animal use in the Middle East and Egypt are based on studies of the ecological, reproductive, productive, physiological and behavioral characteristics of domestic cattle, sheep, goats and pigs. These models help us make predictions. |

“The royal administrators had to develop a system that encouraged the production of animals beyond the needs of the villages of the Nile Delta and the Nile valley. They then collected the surplus and moved it along the Nile to Giza. If the Giza settlement was organized and provisioned by a central authority (the royal administration), then we expect certain evidence to emerge from the archaeological data.

“From our data above, we see that the pyramid settlement at Giza was a well-provisioned site, supplied by the central authority; the archaeological pattern is not one of a livestock producing site. A central authority gathered predominately young, male sheep, goats, and cattle and brought them to the site to feed the occupants; the bones of these animals dominate the faunal remains and pigs are in very little evidence. |

“Without a central authority, this surplus creates a labor problem for herders and agriculturists. Do they reduce the herd size or increase meat consumption seasonally? It would therefore have been relatively easy for administrators to encourage villages to increase production. The central authority then becomes a convenient market for the surplus in exchange for goods and services. Imagine a division across the Nile Delta or Valley: cattle and goats in the middle and sheep and goats along the edges. Sheep and goats would go out into the high deserts in the rainy season and returned to the edges of the delta or valley in the dry season.” |

Animals Consumed by the Giza Pyramid Builders

Dr. Richard Redding and Brian V. Hunt wrote: “Pigs would have been unsatisfactory for provisioning a workforce on a large-scale in the ancient world. They cannot be herded and do not travel well over long distances. There are no nomadic pig herders anywhere in the world today. Pigs have a dispersed birthing pattern that is not seasonal; they give birth up to three times a year. Therefore, young pigs are available at almost anytime for consumption. Pigs provided no secondary products (hair, milk, etc.) and were therefore less valuable than cattle, sheep, and goats. Because of the pig’s unsuitability for feeding workers on a large scale, the Egyptian workforce administrators were not interested in them as stock, and pigs were not involved in inter-regional exchange the way other animal stocks like cattle, sheep, and goats were. [Source: Dr. Richard Redding, Archaeozoologist, University of Michigan and Brian V. Hunt, Ancient Egypt Research Associates., ancientfoods.com, January 11, 2012 |]

“Our studies indicate, however, that while the central authority did not consider pigs a valued provisioning resource, Egyptian families reared pigs for protein. Even today, in rural and urban areas around the world, farmers and non-farmers use pigs (where they are not proscribed by religion). |

“We know that the Egyptians recorded regular and detailed counts of animal stocks throughout the Nile Valley. These counts are a clear indication of the value of animals as a commodity to the state. Although they cannot provide the quantity of meat that cattle do, sheep and goats are valuable for similar reasons. They can be herded and provide secondary products. |

“Sheep, goats, and cattle can and do travel long distances. Americans in the 19th century drove cattle to market over vast distances. Nomadic sheep and goat pastoralists today move animals 1,000 miles (1,609 kilometers) by hoof in migration (e.g. Qashghi in Iran). In the 4th Dynasty, it was not possible to rear sheep, goats, and cattle around Giza in the numbers needed for the pyramid builders. We are working on an estimate of the farm area required to rear these animals in sufficient numbers to provide a surplus that would support 8,000-10,000 workers laboring at ancient Giza. Preliminary estimates suggest a required area substantially larger than the Giza environs would allow.

In Egypt, ranchers would have raised cattle in grassy areas with wells and watering holes like the Nile Delta. They would have raised sheep in the drier areas. Goats could have thrived in both places and would have complimented cattle rearing because these animals do not compete for food. The administrators would have organized drives of sheep, goats, and cattle between the Nile Valley and the high desert to move the required animals to Giza. In a foreshadowing of modern manufacturing, the animals would arrive in waves—a “just in time” delivery system. |

“Sheep, cattle, and goats all have secondary products beyond their meat: Sheep’s wool can be woven for cloth. Leather is valuable for clothing and tools. Cattle bones can be used to make tools. The ancient inhabitants may also have consumed milk from cows and goats, but not in such large quantities that it would have been signficant for the diet of the pyramid labor force. Secondary produce makes all of these animals more valuable resources. Sheep and goats have tight birthing seasons (compared to pigs) and produce age classes from which the young male surplus needs to be harvested. As with cattle, female sheep and goats are needed to produce offspring, while only a few males are needed for breeding.” |

Kom el-Hisn: the Meat Supply Center for the Giza Pyramid Builders?

fishing

Dr. Richard Redding and Brian V. Hunt wrote: “The Old Kingdom (5th and 6th Dynasty, 2465-2150 B.C.) Egyptian village, Kom el-Hisn, was excavated by archaeologists in 1985, 1986, and 1988. A contradiction appears in the archaeological record there. There is abundant evidence of cattle dung from the Old Kingdom level at Kom el-Hisn, which means there must have been large herds there. Yet the cattle bones indicate two things: the numbers of cattle slaughtered at Kom el-Hisn are relatively few and the bones that exist are from very old or very young individuals. [Source: Dr. Richard Redding, Archaeozoologist, University of Michigan and Brian V. Hunt, Ancient Egypt Research Associates., ancientfoods.com, January 11, 2012 |]

“Where are the prime, young males, which provide the best cuts of beef? The residents were not consuming the cattle they reared and were consuming few of the sheep. They only used very old animals or animals that were very young and ill. The residents of Kom el-Hisn were dependent on the pig as a source of protein and, unsurprisingly, we find a dominance of pig bone at the site. |

“Kom el-Hisn is just 4 kilometers from the ecotone where the Nile Valley meets the desert. The Egyptians could have reared cattle in the grassy areas around their villages and sent herders out with flocks of sheep and goats to exploit the ecotonal area. The royal cattlemen periodically gathered up herds of young, male cattle and sheep (1 to 2 years) and drove them along the Nile to a central point for redistribution. These young male animals were not consumed locally and so their remains did not enter the archaeological record at Kom el-Hisn. |

“Cattle were raised at Kom el-Hisn but not consumed there. Where were the consumers? We hypothesize that Kom el-Hisn was a regional or provincial center for raising cattle, but that the young males were sent to the core area of the Old Kingdom state—the capital zone and the pyramid zone—for feeding cities. Our systematic excavations and retrieval of animal bone from such core-area settlements, like Giza, allow us to test our hypothesis. In fact, we find the inverse ratios of Kom el-Hisn: lots of cattle, sheep, and goat but very little pig.” |

Meat Preparation in Ancient Egypt

food case, probably containing a preserved pigeon

We know very little unfortunately of how the dishes were prepared. The favorite national dish, the goose, was generally roasted over live embers; the spit is very primitive — a stick stuck through the beak and neck of the bird. They roasted fish in the same way, sticking the spit through the tail. The roast did not, of course, look very appetising after this manner of cooking, and it had to be well brushed by a wisp of straw before being eaten. A low slab of limestone served as a hearth; even the shepherds, living in the swamps with their cattle, took this apparatus about with them. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

In the kitchen of Ymery, superintendent of the domain of King Shepseskaf, the hearth is replaced by a metal brasier with pretty open-work sides. In the same kitchen we see how the meat is cut up on low tables and cooked; the smaller pots have been placed on a brasier, the large ones stand on two supports over the open fire.

It is only when we come to the time of the New Kingdom that we find, in representations of the kitchen of Ramses III., a great metal kettle with feet standing on the fire; the kitchen boy is stirring the contents with an immense two-pronged fork. The floor of the whole of the back part of the kitchen is composed of mud and little stones, and is raised about a foot in order to form the fireplace, above which, under the ceiling, extends a bar on which is hung the stock of meat.

Tale of Horus and the Pig: Why Egyptians Don’t Eat Pork

Coffin Text: The Tale of Horus and the Pig, (c. 1900 B.C.): Why the Egyptians did not eat pork: “O Batit of the evening, you swamp-dwellers, you of Mendes, ye of Buto, you of the shade of Re which knows not praise, you who brew stoppered beer — do you know why Rekhyt [Lower Egypt] was given to Horus? It was Re who gave it to him in recompense for the injury in his eye. It was Re — he said to Horus: "Pray, let me see your eye since this has happened to it" [injured in the fight with Seth]. [Source: A. de Buck, “The Egyptian Coffin Texts,” (Chicago, 1918), p. 326, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt, Fordham University]

Then Re saw it. Re said: "Pray, look at that injury in your eye, while your hand is a covering over the good eye which is there." Then Horus looked at that injury. It assumed the form of a black pig. Thereupon Horus shrieked because of the state of his eye, which was stormy [inflamed]. Horus said: "Behold, my eye is as at that first blow which Seth made against my eye!" Thereupon Horus swallowed his heart before him [lost consciousness].

Then Re said: "Put him upon his bed until he has recovered." It was Seth — he has assumed form against him as a black pig; thereupon he shot a blow into his eye. Then Re said: "The pig is an abomination to Horus." "Would that he might recover," said the gods. That is how the pig became an abomination to the gods, as well as men, for Horus' sake...”

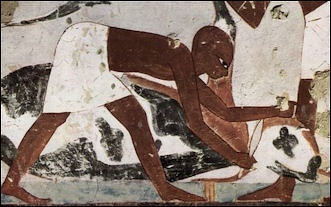

livestock

World’s Oldest Cheese Found in Saqqara, Egypt

In a study published July 25, 2018 in the journal Analytical Chemistry, researchers announced they had discovered the world’s oldest cheese along with a mummy in Saqqara, Egypt, adding the cheese may have been contaminated. Brandon Specktor wrote in Live Science: “The cheese was discovered among a large cache of broken clay jars inside the tomb of Ptahmes, former mayor of Memphis and a high-ranking official during the reigns of pharaohs Seti I and Ramses II. The tomb is thought to have been built in the 13th century B.C. , making it — and the cheese within — about 3,300 years old. [Source: Brandon Specktor, Live Science, August 17, 2018]

“Researchers from the University of Catania in Italy and Cairo University in Egypt stumbled upon the cache during an excavation mission in 2013-14. Inside one of the fragmented jars, they noticed a powdery, “solidified whitish mass.” Nearby, they found a scrap of canvas fabric that was likely used to preserve and cover the ancient blob of food. The texture of this fabric suggested that the food had been solid when it was interred alongside Ptahmes a few millennia ago — in other words, the find probably wasn’t a jar of ancient spoiled milk. ||

“To be sure about this, the researchers cut the cheese and took a small sample back to the chemistry lab for analysis. There, the team dissolved the sample in a special solution to isolate the specific proteins inside. The analysis revealed that the cheese sample contained five separate proteins commonly found in Bovidae milk (milk from cows, sheep, goats or buffalo), two of which were exclusive to cow’s milk. The researchers concluded that the sample was probably a “cheese-like product” made from a mixture of cow’s milk and either goat or sheep milk. “The present sample represents the oldest solid cheese so far discovered,” the researchers wrote in their study. ||

“Of course, this being mummy cheese, there must be a curse attached, right? In this case, that curse might just be a nasty foodborne infection. According to the team’s protein analysis, the cheese also contained a protein associated with Brucella melitensis, a bacterium that causes the highly contagious disease brucellosis. The disease is commonly spread from bovine animals to humans through unpasteurized milk and contaminated meat. Symptoms include severe fever, nausea, vomiting and various other nasty gastrointestinal ailments. “If the cheese is indeed infected with Brucella bacteria, that makes the find the “first biomolecular direct evidence of this disease during the pharaonic period,” the researchers wrote. Further study is required to say for sure whether the protein in question came from a contaminated animal,

In September 2022, archaeologists uncovered a collection of pottery vessels — one containing ancient cheese — at the Saqqara necropolis, Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities said. The pottery had Demotic writing on them, an ancient Egyptian script. Inside were blocks of white cheese. The Miami Herald reported: The cheese dated back to the 26th or 27th Egyptian dynasty, archaeologists said, or about 2,600 years ago. Researchers identified the cheese as halloumi. Halloumi is a type of cheese from Cyprus, known for its characteristic squeak, All Recipes says. The cheese tastes “slightly tangy” and has a “salty flavor with a spongy texture.” [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, September 23, 2022]

shepherd

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024