FARMERS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

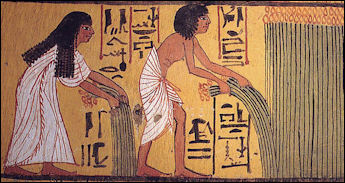

harvest Most Egyptians were tenant farmers. The land they worked was owned by the government. The Egyptians called the Nile Valley flood plain “ kemet” , the black land. The fertile soil was tilled with hoes and wooden plows pulled by oxen and the ember seeds were planted by singing sowers carrying baskets. Water from the hand-dug irrigation canals was collected in heavy jars and carried with a shoulder-mounted yoke to the plants that needed nourishment.

The reason that the small land of Egypt has played as important a part in the history of civilization as many a large empire, is due to the wealth which yearly accrues to the country from the produce of the soil; agriculture is the foundation of Egyptian civilization. The results which the agriculturists of the Nile valley have obtained, they owe however, not to any special skill or cleverness on their part, but to the inexhaustible fertility of the land. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

See Separate Article: IMPORTANT EARLY DEVELOPMENTS IN AGRICULTURE: PLOUGHING, FERTILIZER AND IRRIGATION factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A History of Ancient Egypt: From the First Farmers to the Great Pyramid” by John Romer (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of the First Farmer-Herders in Egypt: New Insights into the Fayum Epipalaeolithic and Neolithic” by N. Shirai (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Ancient Agriculture (Blackwell) by David Hollander and Timothy Howe (2020) Amazon.com;

“Domestic Plants and Animals: The Egyptian Origins” by Douglas J. Brewer, Donald B. Redford, et al. (2024) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

"First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies" by Peter Bellwood (2004) Amazon.com;

“Birth Gods and Origins Agriculture” by Jacques Cauvin (2008) Amazon.com;

“Behavioral Ecology and the Transition to Agriculture” by Douglas J. Kennett and Bruce Winterhalder (2006) Amazon.com;

“Life in Neolithic Farming Communities: Social Organization, Identity, and Differentiation” by Ian Kuijt (2006) Amazon.com;

Crops in Ancient Egypt

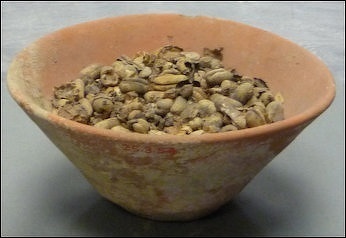

The Egyptians cultivated barley, emmer wheat, beans, chickpeas, flax, and other types of vegetables. They ate a low-fat, high-fiber diet with a lot of grains and consumed a variety of plant oils and fats, bread, milk, lentils, cottage cheese, cakes, onions, meat, dates, melons, milk products, figs, ostrich eggs, almonds, peas, beans, olives, pomegranates, grapes, vegetables, honey, garlic and other foods. The Egyptians ate a variety of grains, including barely and emmer-wheat. Barley was used for making beer. Emmer wheat was used to make bead. Lentils were discovered in an Egyptian tomb dating back to 2000 B.C.).

John Baines of the University of Oxford wrote: “The principal crops were cereals, emmer wheat for bread, and barley for beer. These diet staples were easily stored. Other vital plants were flax, which was used for products from rope to the finest linen cloth and was also exported, and papyrus, a swamp plant that may have been cultivated or gathered wild. Papyrus roots could be eaten, while the stems were used for making anything from boats and mats to the characteristic Egyptian writing material; this too was exported. A range of fruit and vegetables was cultivated. Meat from livestock was a minor part of the diet, but birds were hunted in the marshes and the Nile produced a great deal of fish, which was the main animal protein for most people. [Source: John Baines, BBC, Professor of Egyptology at the University of Oxford, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Bowl of dates from Ancient Egypt

Some monuments depict another cultivated plant that was not wheat or barley. It had a stalk with a small red fruit at the top. This had been recognised with great probability as the black millet, the durra of modern Egypt. Durra was not cut, but pulled up; the earth was then knocked off the roots, after which the Ions: stalks were tied together in sheaves. To get the seed off the stalks a curious instrument something like a comb was used. In a picture an old slave whose duty it was to do the combing was seated in the shade of a sycamore; he pretends that the work was no trouble, and remarks to the peasant, who brings him a fresh bundle of durra to comb: "If thou didst bring me even eleven thousand and nine, I would yet comb them. " The peasant however pays no attention to this foolish boast; “Make haste," he says, “and do not talk so much, thou oldest amongst the field laborers. " [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “One of the most prized products of the Nile and of Egyptian agriculture was oil. Oil was customarily used as a payment to workmen employed by the state, and depending on the type, was highly prized. The most common oil (kiki) was obtained from the castor oil plant. Sesame oil from the New Kingdom was also cultivated and was highly prized during the later Hellenistic Period.” [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

See Separate Article: FOOD IN ANCIENT EGYPT: FRUIT, VEGETABLES, SPICES, EATING CUSTOMS africame.factsanddetails.com

First Crops, Einkorn and Emmer Wheat

The earliest crops were wheat, barley, various legumes, grapes, melons, dates, pistachios and almonds. The world's first wheat, peas, cherries, olives, rye, chickpeas and rye evolved from wild plants found in Turkey and the Middle East. Scientists have found genetic evidence that the world's four major grains — wheat, rice, corn and sorghum — evolved a common ancestor weed that grew 65 million years ago.

The first domesticated crop is believed to have been einkorn wheat, a kind of nourishing grass adapted from a wild species of grass native to the Karacadag mountains near Diyarbakir in southwestern Turkey first cultivated around 11,000 years ago. Scientists deduced this by examining the DNA of modern strains of einkorn wheat and found the were more similar to einkorn wheat grown in the Karacadag mountains than in other places. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, November 20, 1997]

Collecting seeds from wild grass is not an easy matter. If you pick the seeds before they are ripe they are too small and hard to eat. If you wait so long they fall from the stem and you have to pick them up one by one. With some grasses the period in which the seeds are feasible to collect is only a few days a year. If one wants to get a long term food supply it makes sense to collect as much as you can and take it back to your cave and store it.

Emmer wheat, rye and barley were cultivated around the same time, and is difficult to say which was cultivated first. Emmer wheat and another wheat strain from the Caspian Sea are thought to be the first bread wheats. Emmer wheat is a wild grass. It is thought to have been singled out because its seeds stay attached to the stem significantly longer than that of other grasses.

Cereals were being cultivated in what is now Syria. Lebanon, Israel and Palestine around 10,000 years ago in the 8th millenniums B.C. Barley was first grown in the Jordan valley about 10,000 years ago. The earliest levels of excavations at Jericho indicate that the people that lived there collected seeds of cereal grass from rocky crags flanking the valley and planted them in the fertile alluvial soil.

See Separate Articles: FIRST GRAINS AND CROPS: BARLEY, WHEAT, MILLET, SORGHUM, RICE AND CORN factsanddetails.com ; EARLIEST NON-GRAIN CROPS: NUTS, FIGS, BEANS, OLIVES, FRUIT AND POTATOES factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egypt’s Agrarian Society

Sally Katary of Laurentian University wrote: “Since ancient times, Egypt has been blessed by an environment capable of producing large surpluses as a result of the annual renewal of the rich topsoil by the Nile inundation. The extension of a system of basin irrigation during Pharaonic times and canal irrigation in Ptolemaic times allowed Egyptian cultivators to successfully alternate food crops with industrial crops such as flax for both domestic and foreign markets. The proportion of various crops in the domestic and foreign export markets over the millennia is a reflection of the needs and priorities of the underlying system of landholding over time and in different places. [Source: Sally Katary, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“In the context of the broad patterns of settlement and demography, the village is certainly the basic unit in the agricultural regime. The Egyptian landscape underwent dramatic changes over time in settlement patterns, social culture, and hierarchies of settlements, against a backdrop of tremendous regional variation that was dependent upon local traditions and social organization. While this is not the place for discussions of settlement and demography, these are related topics that require exploration in relation to both land tenure and the urban/rural dynamics that characterize the relationship between local power structures and central power structures.”

Heqanakhte: A Farmer in Ancient Egypt

John Ray of Cambridge University wrote for the BBC: “The life of the farmer Heqanakhte is known from a series of short letters, found in the 1920s on the west bank at Luxor, the modern equivalent of ancient Thebes. They are now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The readings here are a series of extracts from a range of his letters. Some were sent to a man called Merisu, written by his father, the same Heqanakhte. Merisu threw the letters into a tomb-shaft, where they were found 4000 years later. They are bad-tempered and judgmental, but reveal a timeless family story. [Source: John Ray, Cambridge University, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Heqanakhte lived at the end of the Eleventh Dynasty. He eked out a living through agriculture, and was a mortuary priest, which would have meant extra income for the family. Most of his sons are grown up, and apparently their mother is no longer alive. However, the father has taken a new wife, causing much resentment. A spoilt younger son, Sneferu, is the favourite. He, the father urges, should be excused unpleasant tasks and should not be accused of idling; indeed, his allowance is to be increased in view of all the criticism he has endured. To the sons, Sneferu is like anyone else, but Heqanakhte will not see this. All this is narrated against a background of whining from the father, labouring on behalf of an ungrateful family. |::|

“The old man also thinks his bride is being ill-treated; he accuses the family of molesting her and spreading malicious rumours. People are at breakpoint-the sons and most of the family on one side, and Heqanakhte, the bride and possibly Heqanakhte's formidable mother on the other. A crisis is at hand. |::|

“The outcome of this fraught situation is unknown, but Egypt at most periods has been the home of blood feuds, which can work their way down over centuries. One person who took a pessimistic view of Heqanakhte's affairs was the crime-writer Agatha Christie, who turned the contents of the letters into a murder mystery, Death Comes As The End (1945). Merisu and his brothers, if they could have predicted this, may have felt it was perfect, if belated, justice.” |::|

Poor, Pitiable Agriculture Laborers of Ancient Egypt

Despite the prestige attached to agricultural work, the occupation of agricultural laborer could quite pitiable. The following sad sketch of the lot of the harvestmen was written by the compiler of a didactic letter, of which many copies were extant, and implies not only a personal opinion but the general view of this matter: “The worm had taken the half of the food, the hippopotamus the other half; there were many mice in the fields, the locusts had come down, and the cattle had eaten, and the sparrows had stolen. Poor miserableagriculturist! What was left on the threshing-floor thieves made away with. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Then the scribe lands on the bank to receive the harvest, his followers carry sticks and the Africans carry palm rods. They say, ' Give up the grain' — there was none there. Then they beat him as he lies stretched out and bound on the ground, they throw him into the canal and he sinks down, head under water. His wife was bound before his eyes and his children were put in fetters. His neighbours run away to escape and to save their grain. "

This is, of course, an exaggerated picture, which was purposely overdrawn by the writer, in order to emphasise the striking contrast that he draws in his eulogy of the profession of scribe; in its main features however it gives us a very true idea, for the lot of the ancient peasant very much resembled that of the modern fellah. The latter labors and toils without enjoying the results of his own work. He earns a scanty subsistence, and, notwithstanding all his industry, he gains no great renown amongst his countrymen of the towns; the best they could say of him is, that he was worthy to be compared with his own cattle.

Dealing with the Nile Inundation

The nourishment that crops need was replenished without any human aid each summer by the inundation of the Nile — which "supplies all men with nourishment and food. " The great river however did not bestow its gifts impartially, it also the caused of misfortune. While a high inundation brings nourishment increase to fields over a vast area, a low Nile brings potential famine. The inundation brings with it, not only the fertile mud, but the needful water for the soil. In this rainless country plants can only grow on those spots that have not been overflowed, but also sufficiently saturated with the water; where this is not the case the hard clay soil is quite bare of vegetation. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

At the same time even the highest inundation does not overflow all the fields, and if these are not to be barren the peasant must undertake an artificial irrigation. The water of the Nile is brougrht as near as possible to his field by a trench, and he then erects a kind of draw-well, now called by the modern term shaduf, though it has retained its old form. It is hard work the whole Hvelong day to raise and empty the pail of the shaduf, in fact nothing is so tiring in the daily work of the Egyptians as this irrigation of the fields. At the present time, when the system of cultivation has been so immensely improved, the fellahin use it most extensively, especially in Upper Egypt; in old times the shaduf was perhaps employed less frequently.

The inundation over, the Nile withdraws, leaving pools of water standing here and there on the fields. This is the busy time of the year for the Egyptian farmer, “the fields are out “and he must “work industriously “so as to make good use of the blessing brought by the Nile. He can do this the better as the sultry heat, which during the summer had oppressed both him and his cattle, has at length given way. “A beautiful day, it is cool, and the oxen draw well; the sky is according to our desire," say the people who till the ground, and they set to work with good will, “for the Nile has been very high," and wise men already foretell that “it is to be a beautiful year, free from want and rich in all herbs," a year in which there will be a good harvest, and in which the calves will “thrive excellently. "

Ploughing in Ancient Egypt

The first duty of the farmer was to plough the land; this work was the more difficult because the plough with which he had to turn over the heavy soil was very clumsy. The Egyptian plough changed but little; from the earliest period it consisted of a long wooden ploughshare,' into which two slightly-bent handles were inserted, while the long pole, which was tied on obliquely to the hinder part of the ploughshare, bore a transverse bar in front, which was fastened to the horns of the oxen. Such was the stereotyped form of plough, which for centuries had scarcely altered at all; for though during the Middle Kingdom another rope was added to bind the pole and ploughshare together, and again during the New Kingdom the handles were put on more perpendicularly and provided with places for the hands, yet these alterations were quite unimportant. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Two men were needed for ploughing — one, the ploughman proper, pressed down the handles of the plough, the other, the ox-driver, was indefatigable in goading on the animals with his stick. The work went on with the inevitable Egyptian cries; the driver encouraged the ploughman with his “Press the plough down, press it down with thy hand! “he calls to the oxen to “pull hard," or he orders them, when they had to turn at the end of the field, to be “round. " There were generally two ploughs, the one behind the other, probably in order that the second might turn up the earth between the furrows made by the other.

If the Egyptians wanted to loosen the upper coating of mud, they employed — at least during the New Kingdom — a lighter plough that was drawn by men. Here we see four boys harnessed to the bar, while an old man was pressing down the handles. This plough also differed somewhat from the usual form; the ploughshare consists of two parts bound together, it had also a long piece added on behind and turned upwards obliquely, by which the ploughman guides the plough.

After ploughing however the great clods of the heavy Egyptian soil had to be broken up again before the ground was ready for the seed. From a public tomb at Thebes we can see that during New Kingdom a roller covered with spikes was drawn over the fields for this purpose; in old times a wooden hoe was use. The latter seems indeed to had been the national agricultural implement. We could had scarcely formed a correct idea of it from the figure in the hieroglyphs and on the reliefs, Fortunately we have some examples of real hoes in our museums. The laborer grasped the handle of this hoe at the lower end and broke up the clods of earth with the blade; by moving the rope he could make it wider or narrower as he pleased. In the pictures of the Old Kingdom, the men hoeing were always represented following the plough; later, they appear to had gone in front as well; during the New Kingdom we meet with them also alone in the fields, as if for some crops the farmers dispensed with the plough and were content with hoeing the soil. In the above-named periods wooden hammers were also employed to break up the clods of earth.

Sowing Seeds and Harvesting in Ancient Egypt

After the land had been properly prepared, the sowing of the seed followed. We see the “scribe of the grain “gravely standing before the heap of seed, watching the men sowing, and noting down how often each filled his little bag with seed. When the seed had been scattered, the work of sowing was not complete — it had next to be pressed into the tough mud. For this purpose sheep were driven over the freshly-sown fields. In all the pictures of this subject one or two shepherds with their flocks were to be seen following the sower. Laborers swinging their whips drive the sheep forward; others no less energetically chase them back. The frightened animals crowd together; a spirited ram appears to be about to offer resistance — he lowers his head in a threatening attitude; most of the creatures, however, run about the field in a frightened way, and help plough it. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

This trampling in of the seed was only represented in the pictures of the Old Kingdom; the custom probably continued later, but became less common. When Herodotus traveled in Egypt, he noticed that pigs were employed in the Delta for this purpose; in Pliny's time this practice was spoken of as a long-forgotten custom of doubtful credibility.

When harvest-time came, the grain was cut by means of a short sickle, with which, contrary to our custom, they cut the stalks high above the ground — sometimes close to the ears'' — as if the straw were useless, and only added to the difficulty of threshing. The work proceeded quickly, as we see from the rapid movements of the men; amongst them however we often find an idle laborer standing with his sickle under his arm; instead of 'working, he preferred to reckon up on his fingers to his comrades how many sheaves he had already cut on that day. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

When the grain had been cut it was bound in sheaves; and as the stalks were too short for one bundle to form a sheaf, two bundles were laid with their ends together, the ears outwards, and then this double sheaf was tied together in the middle with a rope. ' A messenger was sent with a particularly fine specimen to the owner of the property, that he may see how good the crop is;-'' the rest was put up on the field in heaps containing three or four bundles each. The ears that had been dropped were collected in little bags by the gleaning women. '

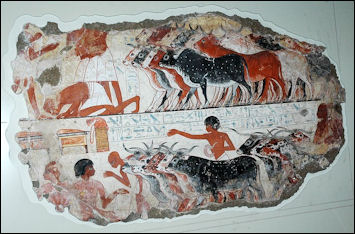

Donkeys and Threshing in Ancient Egypt

After harvesting grain was taken to the threshing-floor, which was probably located near the town. It was carried on the backs of those patient animals — even now the beasts of burden of modern Egypt — the donkeys. We may see quite a number of them being driven in wild career on to the fields,' their drivers behind them calling out to them and brandishing their sticks. On the way they meet the animals returning home with their loads; amongst them was a donkey with her foal. With her head raised she greets the company with a loud bray; but the sticks of the drivers admit of no delay. Soon enough any foolish resistance was over. The donkeys arrive on the harvest-field ready to be laden with the sheaves; one of the animals then kicks up his heels, and refuses to come alongside. One of the drivers pulls him by the ears and leg, another beats him; “run as thou canst," they cry to him, and drag him up to the lading place. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

In the meantime the sheaves had been tied up in a large basket or sack,° or they may had been, as was apparently customary later, packed in panniers/ which were hung over the saddle of the donkey. When the donkeys were laden, one sheaf, for which no room could be found, was put in the basket," and the procession sets off. They went slowly enough, though the men never cease calling out to their beasts to “run," but the donkeys were heavily laden, and one stumbles under his burden. The driver guides him by the tail; his boy, who had to see that the load was rightly balanced, pulls him by the ear.

When they arrive at the grain stack, which had been raised in the threshing-floor, the sheaves were divided, and two workmen busy themselves with throwing up the separate bundles of ears on to the stack. Great skill and strength seem to had been necessary for this work, so that by a powerful throw the stack might be made as firm as possible; a third workman was often to be seen gathering together one by one the ears that had fallen below. The threshing-floor, in the midst of which appears to had been the stack,' is, to judge from the pictures, a flat round area, with the sides some what raised. " The grain was spread out here, and trodden by the hoofs of the animals driven about in it.

During the Old Kingdom the animals used for this purpose were nearly always donkeys,' and oxen were only met with when, as we may say, extra help was wanted; '' after the time of the Middle Kingdom however, the Egyptians seem to had followed a different plan, for we find that in later times oxen were employed alone. As a rule, when donkeys were used, ten animals were employed, but in the case of oxen three were considered sufficient. They were driven round the floor in a circle, and the stick and the voice were of course in great request, for donkeys were particularly self-willed creatures. As we see, one wants to run the other way, another will not went forward at all, so that there was nothing to do but to seize him by the fore leg and drag him over the threshing-floor. We often see an ox or a donkey munching a few ears while threshing, as if to illustrate the Hebrew maxim that “thou shalt not muzzle the ox that treadeth out the grain. "

After Threshing — Tallying by the Grain Officials

After the grain had been threshed, it was collected, together with the chaff, by means of a wooden fork, into a big heap, which was weighted at the top in order to keep it together. The next necessary work was to sift the grain from the chaff and dirt. This work seems always to had been performed by women. They winnow the grain by throwing it up quickly by means of two small bent boards. The grain falls straight down while the chaff was blown forwards. The grain had already been passed through a great rectangular sieve to separate it from the worst impurities. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

A sample of the freshly-threshed grain was then sent to the master to see; the harvest-men also did not forget to thank the gods. They not only dedicated the first-fruits to the god specially revered in the locality,' and celebrated a festival to Min, the god of agriculture,' but also during harvesttime the peasants gave thanks to heaven. In one example, for instance, we find two little altars erected near the threshing-floor between the heaps of grain and in another a little bowl was placed on the heap of grain that a woman had piled up; “both were doubtless offerings to the snake goddess, Renenutet; the altars and chapels that we meet with in the courts of the granaries were also probably erected to her honour.

Finally, at the close of the harvest, two officials belonging to the estate come on the scene, the “scribe of the granary “and the “measurer of the grain. " They measured the heaps of grain ' before they were taken into the granary. These granaries were, at all periods, built essentially on the same plan. In a court surrounded by a wall were placed one or two rows of conical mud buildings about five meters (16 feet) high; they had one little window high up, and another half-way up or near the ground. The lower one, which served for taking away the grain, was generally closed on account of the mice, and the workmen emptied their sacks through the upper window, which was reached by a ladder. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

During the Middle Kingdom we find also a somewhat different form. These granaries had all, as a rule, a flat roof reached by an outside staircase; the roof formed a good vantage ground for the scribe, from which he could keep account of the sacks that were brought up and emptied into the granary. Such a granary was only suitable for a large establishment, for a property, for instance, like that of Pahre of El Kab, who lived at the beginning of the eighteenth dynasty, where we see the harvest brought by great ships to the granary; the workmen who were carrying the heavy sacks of grain on board break out at last into complaints: “Are we then to had no rest from the carrying of the grain and the white spelt? The barns were already so full that the heaps of grain overflow, and the boats were already so full of grain that they burst. And yet we were still driven to make haste. "

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024