Home | Category: Government, Military and Justice

QUEENS OF ANCIENT EGYPT

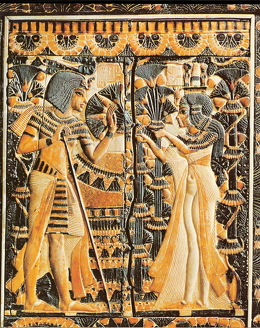

The Pharaoh had only one legal wife — the queen. She was of royal or of high noble birth, and may have been the “daughter of the god" such as of the late king, and therefore the sister of her husband. Her titles testify to her rank at court. Tthe queen of the Old Kingdom was called “She who sees the gods Horus and Seth.. the possessor of both halves of the kingdom, the most pleasant, the highly praised, the friend of Horus, the beloved of him who wears the two diadems.” The queen during the New Kingdom was called “The Consort of the god, the mother of the god, the great consort of the King; “" and her name is enclosed like that of her husband in a cartouche. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The queen appears as a rule to have been of equal birth with her husband; she took her share in all honours. Unfortunately the monuments always treat her as an official personage, and therefore we know scarcely anything of what took place in the “rooms of the royal wife. " The artists of the heretic king Akhenaten in rare fashion emancipate themselves from conventionalities, and give us a scene out of the family life of the Pharaoh. We see him in an arbour decked with wreaths of flowers sitting in an easy chair, he has a flower in his hand, the queen stands before him pouring out wine for him, and his little daughter brings flowers and cakes to her father.

After the death of her husband the queen still played her part at court, and as royal mother had her own property, which was under special management. " Many of the queens had divine honours paid to them even long after their deaths — two especially at the beginning of the New Kingdom, Ahhotep and Ahmose Nefertari, were thus honoured; they were probably considered as the ancestresses of the 18th dynasty.

See Separate Article: QUEENS OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt” by Elizabeth Payne (1981) Amazon.com;

“The Pharaoh: Life at Court and On Campaign” by Garry J. Shaw (2012) Amazon.com;

“Court Officials of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom” by Wolfram Grajetzki (2009)

Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten's Royal Court: The City at Amarna and Its Officials” by David W Pepper (2022) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

”Private Lives of the Pharaohs: Unlocking the Secrets of Egyptian Royalty” by Joyce Tyldesley (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt: A Genealogical Sourcebook of the Pharaohs” Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of The Pharaohs” by Clayton Peter (1994) Amazon.com;

“The First Pharaohs: Their Lives and Afterlives” by Aidan Dodson (2021) Amazon.com;

“Abydos: Egypt's First Pharaohs and the Cult of Osiris” by David O'Connor (2009) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass (2005) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun: The Life and Death of a Pharaoh” by David Hamilton Murdoch Amazon.com;

"Ramesses II, Egypt's Ultimate Pharaoh" by Peter Brand Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of a Pharaoh: The Intimate Life of Amenhotep III” by Joann Fletcher (2000) Amazon.com;

Harem of the Pharaoh

Besides the chief royal consort, and other consorts, the Pharaoh possessed a harem,'' whose members were secluded under the supervision of a matron." They attended to the pleasures of the monarch. High officials, such as the "governor of the royal harem," the scribe of the same,' the “delegate for the harem " looked after its administration, and a number of doorkeepers prevented the ladies from holding useless intercourse with the outer world. These secluded were some of them maidens of good Egyptian family, but many were foreign slaves. King Amenhotep III received as a gift from a certain prince of Naharina, his eldest daughter and 317 maidens, the choicest of the secluded; We see from this statement what a crowd of women must have lodged in the house of the women belonging to the court of Pharaoh. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

We know scarcely anything of the harem life, except that the members had to provide musical entertainments for the monarch. On one occasion only a king allows us a glimpse into his harem; in the building in front of the great temple of Medinet Habu we see representations of Ramses III, with his ladies. They, as well as their master, are dressed mainly in sandals and necklets, they wear the coiffure of royal children, and therefore some scholars have thought them to be the daughters of the king. But why should the daughters of Ramses III be depicted here and not his sons? It is also quite contrary to Egyptian custom to represent the members of the royal family with no names appended. We can therefore conscientiously consider these slender pretty ladies to be those who plotted the great conspiracy against the throne of Ramses III. of which we have spoken above. In these pictures no indication is given of this plot; the ladies play the favorite game of senet peacefully with their master, they bring him flowers, and eat fruit with him.

Under these circumstances it was natural that posterity should not fail the Egyptian kings, though all did not have so many children as Ramses II, of whom we read that he had 200 children; of these 111sons and 59 daughters are known to us. " In the older periods at any rate special revenues were put aside for the maintenance of these princes. During the Old Kingdom they also received government appointments, such as one called the “treasurer of the god '" had to fetch the granite blocks out of the quarries of the desert; others officiated as high priests in the temple of Heliopolis,'' and others again (bearing the title of “prince of the blood" became the “chief judges “or the “scribes of the divine book," and nearly all of them were, in addition, “Chief reciter-priests of their father," and belonged, as “governors of the palace," to his inner circle of courtiers.

See Separate Article: HAREMS AND POLYGAMY IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Pharaohs Who Married Their Siblings and Children

Among pharaohs and their queens, brothers and sisters and even fathers and daughters intermarried. Incest was a way of keeping property in the family because women could inherent property. Scholars debate whether these marriages were consummated or simply ceremonial.

Describing the implications of a father-daughter marriage, Reay Tannahill wrote in “Sex in History”: "A resulting son would be a half brother of his mother, his grandmother's stepson, his mother's brothers half brother, and not only his father's child but his grandson as well! Note the problems of identity and exercise of authority: should he act toward his mother as a son or as a half-brother; should the uncle be related as an uncle or as a half-brother”...if a brother and sister were to marry then divorce, could they readily revert to their original relationship?"

Egyptian rulers who were married to their siblings include Senwosret I (reigned circa 1961 B.C. to 1917 B.C.), who was married to his sister Neferu; Amenhotep I (reigned circa 1525 B.C. to 1504 B.C.), who was married to his sister Ahmose-Meritamun; and Cleopatra VII (reigned circa 51 B.C. to 30 B.C.), who was married to her brother Ptolemy XIV before he was killed. There are also examples of pharaohs marrying their daughters: Ramses II (reigned circa 1279 B.C. to1213 B.C.) took Meritamen, one of his daughters, as a wife. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, August 26, 2023]

According to Live Science: Pharaohs in Egypt often had multiple wives and concubines, and incestuous marriages sometimes produced children. Some scholars have suggested that inbreeding contributed to the medical problems of Tutankhamun, a team led by Zahi Hawass, a former Egyptian antiquities minister, and colleagues wrote in a 2010 article published in the journal JAMA.

See Separate Article: INCEST AND MARRIAGE IN ANCIENT EGYPT: SIBLINGS, CHILDREN, NOT SO COMMON africame.factsanddetails.com

Princes and Royal Relatives in Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egyptian princes, or, as they are called during the New Kingdom, the “divine offspring," can be recognised by their robes. In later times they also retained during their lifetime the side-lock, the old badge of childhood, though not in its original form, for instead of a plaited lock of hair, they wore a fringed band. The princes were brought up in the home of their father, and in a special part of the palace; their tutor, who was one of the highest court officials, was called, strange to say, their nurse. Pahri, the prince of El Kab under Amenhotep I., was nurse to the prince Uadmes; Semnut, the favorite of Queen Chnemtamun, was nurse to the princess Ra'no fru; ' and Heqerneheh, a grandee at the court of Amenhotep II., had the care of the education of the heir-apparent, Thutmose II., and of seven other princes. " [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

In addition to these male nurses, the real female nurse played an important part at court, such as at-the court of the heretic king Akhenaten, the “great nurse who nourished the god and decked the king “was an influential personage. “Decking the king “signifies some duty the nurse performed at the coronation; in the time of the Middle Empire a “keeper of the diadem “boasts that he had “nourished the god and beautified the Horus, the lord of the palace. '"' There was a pretty custom in the time of the Old and Middle Kingdom: the king allowed other boys to be educated at court with his own sons.

Ptahshepses, who later became high priest of Memphis, was brought Ra “amongst the royal children in the great house of the king, in the room and dwelling-place of the king, and was preferred by the king before all the other boRa died, Shepseskaf, who succeeded him, kept him amongst the princes and honoured him before all the other youths. When Ptahshepses became a man, his Majesty gave him “the great royal daughter Ma'tcha' to wife, and his Majesty wished her to live with him rather than with any other man. " It was the same during the Middle Kingdom, for a nomarch of Aysut relates with pride how he had received swimming lessons with the royal children, and a high officer of the palace boasts that as a child “he had sat at the feet of the king, as a pupil of Horus, the lord of the palace. " Another man relates: “His Majesty seated me at his feet in my youth, and preferred me to all my companions. His Majesty was pleased to grant me daily food, and when I walked with him, he praised me each day more than he had the day before, and," he continues, “I became a real relative of the king. " These last words are easy of explanation: the same honour was bestowed upon him as upon Ptahshepses — he received one of the daughters of the king for his wife.

In the time of the Old Kingdom we continually meet with these “royal relatives," holding different dignities and offices. We can rarely discover what their relationship was to the king, and we suspect that those who were only distantly connected with the royal family made use of this title which had formerly been given to their ancestors. Under the 12th dynasty, it is expressly stated when any one was a “real royal relative," and the words “royal relative," when used alone, began to have an ambiguous meaning.

Courtiers of the Pharaoh

Over and over again we meet phrases praising the Pharaoh such as "He knew the place of the royal foot, and followed his benefactor in the way, he followed Horus in his house, he lived under the feet of his master," he was beloved by the king more than all the people of Egypt, he was loved by him as one of his friends, he was his faithful servant, dear to his heart, he was in truth beloved by his lord.'" in the tombs of the great men, and all that they signify is that the deceased belonged to the court circle, or in the Egyptian language the “Chosen of the Guard. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

" These courtiers watched jealously lest one should approach the monarch nearer than another; there were certain laws, the “customs of the palace and the maxims of the court," which were strictly observed by the officials who "allowed the courtiers to ascend to the king. " This presentation of the courtiers in order of precedence was openly considered as a most important business, and those whose duty it was to “range the princes in their places,' to appoint to the friends of the king their approach when standing or sitting," boast how excellently they performed their duty.

We know little more of the ceremonial of the Egyptian court; the fact that King Shepseskaf allowed Ptahshepses, one of his grandees,to kiss his foot instead of kissing the ground before him, shows us how strict etiquette was even during the Old Kingdom. It is noteworthy that the man chosen out for this high honour was not only the high priest of Memphis, but also the son-in-law of His Majesty. During the Old Kingdom these conventionalities were carried farther than in any later time; and the long list of the titles of those officials shows us that the court under the pyramid-builders had many features in common with that of the Byzantines.

High Officials Close to the Pharaoh

Special titles in ancient Egypt served to signify the degree of rank the great men held with respect to the king. In old times the most important were the friend, and the well-beloved friend of the king. These degrees of rank were awarded at the same time as some promotion in office. A high official of the 6th dynasty received the office of “Under-superintendent of the prophets of the royal city of the dead," and at the same time the rank of “friend "; when later he was promoted to be “Chief of the district of the Nubian boundary," he became the wcll-beloved friend. Promotion to a certain rank was not exactly connected with certain offices, it was given rather as a special mark of favor by the king. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The highest government officials were the “great men of the south”. Judges were called the “overseers "the governors of the vestibule,"' or "the governors of the writing business of the vestibule. Amongst the ''' nearest friends" of king Pepi, was one belonging to the lower rank of “Overseer of Scribes "; in this case he was invested with a title of honour usually reserved for higher officials. ' The princes of the royal household were as a matter of course raised to this rank sooner than others, for whilst as a rule no high priest, no "treasurer of the god," bears the title of ' friend I' the sons of the king holding these positions are often called the “nearest friends “of their father. Though these titles were generally given only to the highest officials, yet some of the “great men of the South “are counted as ''friends',' while many chief judges ' are without this rank. It seems that officers in the palace received it when called to be “Privy-Councillors of the honourable house,"" while the high priests appear, as we have said, to be entirely excluded.

The rank of friend was kept up in later times, though it did not play so important a part as before. During the New Kingdom the title of “fan-bearer on the right hand of the king” was given to princes, judges, high-treasurers, generals, and others of the highest rank. They had the privilege of carrying as insignia, a fan and a small battle-axe of the shape represented below. The axe, symbolic of the warlike character of the New Kingdom, shows that this title was originally given to those of high military rank, and in fact we find some of the standard-bearers and fanbearers in the army “carrying this fan. The fan was also given to ladies, and the maids of honour of the queen and the princesses often bear it. That it was certainly considered a great honour, we judge from the fact that the happy possessor was never depicted without it — even when the hands are raised in prayer, the fan or the axe is represented on the band on the shoulder.

Those who were raised to the rank of "fan-bearer” received also the title of “nearest friend',' which during the New Kingdom signified essentially the same dignity. Similar conservative customs in maintaining names and titles may often be observed during the New Kingdom, such as notwithstanding that all the conditions of the state had altered, yet we see that under Thutmose III the royal bark bears the same name, “Star of the two countries," as the bark of King Khufu fifteen hundred years previously. ''

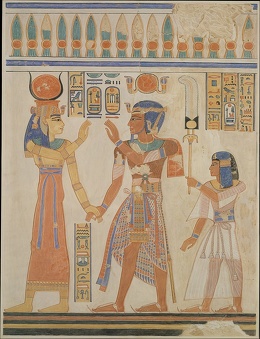

Meeting the Pharaoh

During the Old Kingdom is seems it was customary for people meeting the Pharaoh to kiss his foot or kiss the ground before him. During the New Kingdom this customs appears to have been rather out of fashion, at any rate for the highest officials; the words may occur occasionally in the inscriptions, but in the pictures the princes only bow, either with their arms by their sides or with them raised in prayer before His Majesty. The priests also, when receiving the king ceremoniously at the gates of the temples, only bow respectfully, and even their wives and children do the same as they present the Pharaoh with flowers and food in token of welcome; it is only the servants who throw themselves down before him and kiss the earth at the sight of the monarch.

It seems to have been the custom during the New Kingdom to greet the king with a short psalm when they “spoke in his presence “(it was not etiquette to speak “to him ") — such as when the king had called his councillors together, and had set forth to them how he had resolved to bore a well on one of the desert roads, and had asked them for their opinion on the subject, we might expect them straightway to give him an answer, especially as already on their entrance into the hall they had “raised their arms praising him. "

The princes considered it necessary however to make a preamble as follows: “Thou art like Ra in all that thou doest, everything happens according to the wish of thy heart. We have seen many of thy wondrous deeds, since thou hast been crowned king of the two countries, and we have neither seen nor heard anything equal to thee. The words of thy mouth are like the words of Harmachis, thy tongue is a balance, and thy lips are more exact than the little tongue on the balance of Thoth. What way is there that thou dost not know? who accomplishes all things like thee? Where is the place which thou hast not seen? There is no country through which thou hast not journeyed, and what thou hast not seen thou hast heard. For from thy mother's womb thou hast governed and ruled this country with all the dignity of a child of royal blood. All the affairs of the two countries were brought before thee, even when thou wast a child with the plaited lock of hair. No monument was erected, no business was transacted, without thee. When thou wast at the breast, thou wast the general of the army; in thy tenth year thou didst suggest the plan of all the works, and all affairs passed through thy hands. When thou didst command the water to cover the mountain, the ocean obeyed immediately. In thy limbs is Ra, and Chepre thy creator dwells within thee. Thou art the living image on earth of thy father Atum of Heliopolis. The god of taste is in thy mouth, the god of knowledge in thy heart; thy tongue is enthroned in the temple of truth. God is seated upon thy lips. Thy words are fulfilled daily, and the thoughts of thy heart are carried out like those of Ptah the creator. Thou art immortal, and thy thoughts shall be accomplished and thy words obeyed for ever. "

When the princes had expressed their admiration of the young king in this pretty but in our opinion exaggerated, senseless style, they might then address him directly: “O King, our master," and answer his question.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Amarna Palace, the Amarna Project

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024