Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

INCESTUOUS MARRIAGE IN ANCIENT EGYPT NOT AS COMMON AS CLAIMED

Tutankhamun People in ancient Egypt — both royal and nonroyal — married their relatives, but the details vary according to the time period and class. Ben Gazur wrote in Listverse: The most famous example of a brother-sister marriage in Egyptian mythology is that of Osiris and Isis.When the god Osiris was killed and dismembered by his brother Set, his wife and sister Isis sought to gather up all his body parts. The only one she failed to recover was his penis — which a crocodile ate. Since the Nile had claimed the penis of a god, it became hugely fertile and brought life to the land. In the first mention in recorded history of a blow job, Isis fashioned a new penis out of clay for her brother-husband and blew life into it. [Source Ben Gazur, Listverse, January 7, 2017]

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: Among the general population, brother-sister marriages occurred frequently during the time the Romans controlled Egypt — from 30 B.C. to A.D. 395 — but they were rarer in earlier time periods, according to ancient records. Meanwhile, ancient Egyptian royals sometimes married their siblings — a practice that may have reflected religious beliefs — and pharaohs sometimes married their own daughters. The question of the practice of incest in Ancient Egypt has given rise to much discussion” among scholars Marcelo Campagno, an independent scholar who holds a doctorate in Egyptology, told Live Science. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, August 26, 2023]

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Instances of incest were once thought to be commonplace in ancient Egypt. This has been proven false with the discovery of the semantics of the Egyptian language. When the scholars were first deciphering the hieroglyphs they ran into many references of women and men referring to their spouse as their “brother” or "sister." The terms Brother and Sister reflected the feelings that two people shared, not the hereditary kinship relationship. “My brother torments my heart with his voice, he makes sickness take hold of me; he is neighbor to my mother’s house, and I cannot go to him! Brother, I am promised to you by the Gold of Women! Come to me that I may see your beauty.” [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Jaana Toivari-Viitala wrote: “Marriage between close kin was not taboo in ancient Egypt, but the evidence for such couplings outside the royal family is meager. A possible, and as it would seem, the earliest attested case of a brother- sister marriage is found in the tomb of Hem- Ra/Isi I at Deir el-Gabrawi. From Middle Kingdom sources at least two certain and another three possible marriages between half-siblings have been attested. There are also some attested New Kingdom and Late Period sibling marriages in addition to the above mentioned Deir el-Medina case, but the practice does not seem to have been specifically common until the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods (332 B.C. - 394 CE). Unions between fathers and daughters are occasionally mentioned within the royal family, but they appear not to have occurred among commoners. As sexual intercourse between parent and child is presented as a deterrent in the threat-formulae, such unions were probably considered inappropriate, at least among non-royal persons.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Blood Is Thicker Than Water’ – Non-Royal Consanguineous Marriage in Ancient Egypt: An Exploration of Economic and Biological Outcomes” by Joanne-Marie Robinson (2020) Amazon.com;

“An Incestuous and Close-Kin Marriage in Ancient Egypt and Persia: Examination of the Evidence” by Paul John Frandsen (2009) Amazon.com;

“Ceremonies of Love Wedding Traditions in Ancient Egypt” by Oriental Publishing (2024) Amazon.com;

“In Bed with the Ancient Egyptians” by Charlotte Booth (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Harem Conspiracy: The Murder of Ramessess III” by Susan Redford (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Story of Tutankhamun: An Intimate Life of the Boy who Became King” by Garry J. Shaw (2022) Amazon.com;

“Thutmose III and Hatshepsut, Pharaohs of Egypt: Their Lives and Afterlives” by Aidan Dodson (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt: A Genealogical Sourcebook of the Pharaohs” Amazon.com;

”Private Lives of the Pharaohs: Unlocking the Secrets of Egyptian Royalty” by Joyce Tyldesley (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Harem Conspiracy: The Murder of Ramessess III” by Susan Redford (2002) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Marriage, Incest and Inheritance in Ancient Egypt

Marcelo P Campagno of the University of Buenos Aires wrote: “We have no evidence for the existence of rules of preference in the choice of marriage partners. Marriage between cousins, between uncles and nieces, and between half-siblings is known from various periods in Egyptian history. However, marriage between full brothers and sisters was limited to the royal entourage, except during the Roman Period, when the practice occurred in Greek and mixed households. This pattern of evidence does not suggest that Pharaonic Egypt had no prohibitions against incestuous relationships, as is sometimes proposed. First and foremost, the king was a divine being and was therefore beyond such regulations. [Source: Marcelo P Campagno, University of Buenos Aires, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Moreover, relationships that are considered forbidden are culturally variable; in Egypt, incest taboos may have applied to relations between parents and children, or to relations of the so-called “second type incest,” which implies that two consanguineous kin of the same sex could not share the same sexual partner. Monogamous marriage was predominant, although the possibility that a man could have more than one wife was not excluded, especially among the elite. A marriage could be dissolved by divorce, which—at least, during the first millennium B.C.—was subjected to regulations regarding the return of the dowry; such regulations varied according to the causes of the divorce. Adultery between a man and a married woman was morally condemned and, according to literary texts, both parties seem to have been subjected to severe penalties.

“Inheritance seems to have followed the principle of bilateral descent, wherein men and women were allowed to inherit from both parents. However, the eldest son (sA smsw) seems to have received double the portion of the inheritance that his siblings received, presumably because he was responsible for the burial of his parents. In polygamous marriages, the descendants of the first wife appear to have been privileged in their inheritance. Couples without descendants could decide to adopt individuals who were not linked by close blood ties. Sometimes, a man could adopt his own wife in order to transfer his belongings to her. In addition to the inheritance of rights and possessions, there was a strong tendency for professions to be transferred from father to son (for example, in the priesthood and among craftsmen), as well as some political- administrative positions during various periods (such as the office of nomarch at the end of the Old Kingdom).”

Brother-Sister Marriages in Ancient Egypt

In the royal family of the eighteenth dynasty, we find that Ahmose-Nefertari married her brother, Ahmose; a lady named Ahmose was consort to her brother Thutmose I., and 'Ar'at to her brother, Thutmose IV., and so on." In the inscriptions of all ages we often meet with the words “his beloved sister," where we should expect the words “his beloved wife." It is impossible that all these passages should refer to unmarried ladies keeping house for their bachelor brothers; “thy sister, who is in thine heart, who sits near thee “at the feast, or “thy beloved sister with whom thou dost love to speak," these ladies must stand in a closer relationship to the man. At the same time it is probable that these sisters were not all really married to their brothers, as Lessing's Just very rightly remarks, “there are many kinds of sisters." In the Egyptian lyrics the lover always speaks of “my brother “or “my sister," and in many cases there can be no doubt that the sister signifies his “beloved," his mistress. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: Many royal Egyptians entered into brother-sister royal marriages to emulate the practice of Osiris and Isis, two Egyptian deities who were siblings married to each other. "Osiris was one of the most important gods in Egyptian religion. His consort, Isis, was also his sister according to some ancient Egyptian cosmogonies," Leire Olabarria, a lecturer in Egyptology at the University of Birmingham in the U.K., told Live Science. "Thus, royals engaged in close-kin marriage in order to emulate Osiris and Isis, and perpetuate their images as gods on earth." [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, August 26, 2023]

Campagno agreed that the Osiris-Isis marriage helps explain why brother-sister marriage was practiced by Egyptian royalty. Among nonroyals, brother-sister marriage does not appear to have become widespread until the time of Roman rule, when records indicate there were a sizable number of sibling marriages, experts told Live Science. Olabarria cautioned that it may be difficult to detect brother-sister marriage after the start of the New Kingdom (circa 1550 B.C. to 1070 B.C.) because of changes in how Egyptian words were used. For example, "The term 'snt' is usually translated as 'sister' but in the New Kingdom it started to be used for wife or lover as well," Olabarria said.

Brother-Sister Marriages in Ancient Egypt Particularly High During Roman Rule

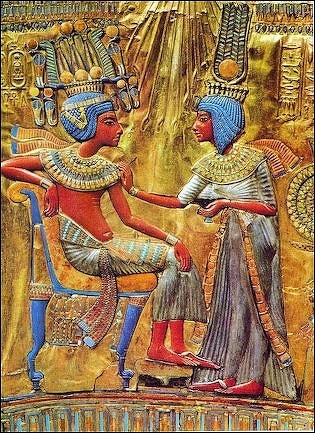

Tutankhamun and his wife

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: Why the number of brother-sister marriages surged during Roman rule is a source of debate. In her book "The Family in Roman Egypt: A Comparative Approach to Intergenerational Solidarity and Conflict" (Cambridge University Press, 2013), Sabine Huebner, a professor of ancient civilizations at the University of Basel in Switzerland, wrote that many of these brother-sister marriages may actually be with a man who was adopted into their wife's family shortly before the marriage. Parents without a son may have wanted this arrangement, as it would have meant that the husband moved into their home rather than their daughter leaving. This would have been important for the financial stability of the parents as they got older, Huebner wrote. This practice of formally adopting a son-in-law occurred in other ancient societies, including Greece. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, August 26, 2023]

The adoption of the son-in-law is the best explanation for why brother-sister marriage is attested so frequently in Roman Egypt, Huebner said. "This seems to me the more obvious case than declaring the society of Roman Egypt the only case in human history where full-sibling marriages were celebrated among the common people at large and on a regular basis," she wrote.

Some scholars are not certain that adoption can explain why brother-sister marriage was frequent in Roman Egypt. "The wording of the Egyptian marriage contracts — 'son and daughter of the same mother and the same father' — pretty well rule out adoption in all of those cases," Brent Shaw, a professor emeritus of classics at Princeton University, told Live Science.

There are other possible explanations for why brother-sister marriages frequently occurred in Roman Egypt. One possibility, Olabarria said, is that parents encouraged it so that property and wealth would not be split up as much when they died. Campagno noted that the practice seems to have occurred largely in parts of the population of Greek descent, and Olabarria said brother-sister marriage may have been used as an identity marker of sorts for Egyptians of Greek descent.

Pharaohs Who Married Their Siblings and Children

Among pharaohs and their queens, brothers and sisters and even fathers and daughters intermarried. Incest was a way of keeping property in the family because women could inherent property. Scholars debate whether these marriages were consummated or simply ceremonial.

Describing the implications of a father-daughter marriage, Reay Tannahill wrote in “Sex in History”: "A resulting son would be a half brother of his mother, his grandmother's stepson, his mother's brothers half brother, and not only his father's child but his grandson as well! Note the problems of identity and exercise of authority: should he act toward his mother as a son or as a half-brother; should the uncle be related as an uncle or as a half-brother”...if a brother and sister were to marry then divorce, could they readily revert to their original relationship?"

Egyptian rulers who were married to their siblings include Senwosret I (reigned circa 1961 B.C. to 1917 B.C.), who was married to his sister Neferu; Amenhotep I (reigned circa 1525 B.C. to 1504 B.C.), who was married to his sister Ahmose-Meritamun; and Cleopatra VII (reigned circa 51 B.C. to 30 B.C.), who was married to her brother Ptolemy XIV before he was killed. There are also examples of pharaohs marrying their daughters: Ramses II (reigned circa 1279 B.C. to1213 B.C.) took Meritamen, one of his daughters, as a wife. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, August 26, 2023]

According to Live Science: Pharaohs in Egypt often had multiple wives and concubines, and incestuous marriages sometimes produced children. Some scholars have suggested that inbreeding contributed to the medical problems of Tutankhamun, a team led by Zahi Hawass, a former Egyptian antiquities minister, and colleagues wrote in a 2010 article published in the journal JAMA.

Royal Incest

The ancient Egyptians were not the only royalty to have close relations among its close relations. David Dobbs wrote in National Geographic, “When New England missionary Hiram Bingham arrived in Hawaii in 1820, he was dismayed to find the natives indulging in idolatry, hula dancing, and, among the ruling family, incest. The Hawaiians themselves did not share Bingham's shock at the royals' behavior. Royal incest, notes historian Joanne Carando, was "not only accepted but even encouraged" in Hawaii as an exclusive royal privilege. [Source: David Dobbs, National Geographic, September 2010]

In fact, while virtually every culture in recorded history has held sibling or parent-child couplings taboo, royalty have been exempted in many societies, including ancient Egypt, Inca Peru, and, at times, Central Africa, Mexico, and Thailand. And while royal families in Europe avoided sibling incest, many, including the Hohenzollerns of Prussia, the Bourbons of France, and the British royal family, often married cousins. The Spanish Habsburgs, who ruled for nearly 200 years, frequently married among close relatives. Their dynasty ended in 1700 with the death of Charles II, a king so riddled with health and development problems that he didn't talk until he was four or walk until he was eight. He also had trouble chewing food and couldn't sire a child.

Amenhotep I

The physical problems faced by Charles and the pharaoh Tutankhamun, the son of siblings, point to one possible explanation for the near-universal incest taboo: Overlapping genes can backfire. Siblings share half their genes on average, as do parents and offspring. First cousins' genomes overlap 12.5 percent. Matings between close relatives can raise the danger that harmful recessive genes, especially if combined repeatedly through generations, will match up in the offspring, leading to elevated chances of health or developmental problems — perhaps Tut's partially cleft palate and congenitally deformed foot or Charles's small stature and impotence.

If the royals knew of these potential downsides, they chose to ignore them. According to Stanford University classics professor Walter Scheidel, one reason is that "incest sets them apart." Royal incest occurs mainly in societies where rulers have tremendous power and no peers, except the gods. Since gods marry each other, so should royals. Incest also protects royal assets. Marrying family members ensures that a king will share riches, privilege, and power only with people already his relatives. In dominant, centralized societies such as ancient Egypt or Inca Peru, this can mean limiting the mating circle to immediate family. In societies with overlapping cultures, as in second-millennium Europe, it can mean marrying extended family members from other regimes to forge alliances while keeping power among kin.

And the hazards, while real, are not absolute. Even the high rates of genetic overlap generated in the offspring of sibling unions, for instance, can create more healthy children than sick ones. And royal wealth can help offset some medical conditions; Charles II lived far better (and probably longer, dying at age 38) than he would have were he a peasant.

A king or a pharaoh can also hedge the risk of his incestuous bets by placing wagers elsewhere. He can mate, as Stanford classicist Josiah Ober notes, "with pretty much anybody he wants to." Inca ruler Huayna Capac (1493-1527), for instance, passed power not only to his son Huáscar, whose mother was Capac's wife and sister, but also to his son Atahualpa, whose mother was apparently a consort. And King Rama V of Thailand (1873-1910) sired more than 70 children — some from marriages to half sisters but most with dozens of consorts and concubines. Such a ruler could opt to funnel wealth, security, education, and even political power to many of his children, regardless of the status of the mother. A geneticist would say he was offering his genes many paths to the future.

It can all seem rather mercenary. Yet affection sometimes drives these bonds. Bingham learned that even after King Kamehameha III of Hawaii accepted Christian rule, he slept for several years with his sister, Princess Nahi'ena'ena — pleasing their elders but disturbing the missionaries. They did it, says historian Carando, because they loved each other.

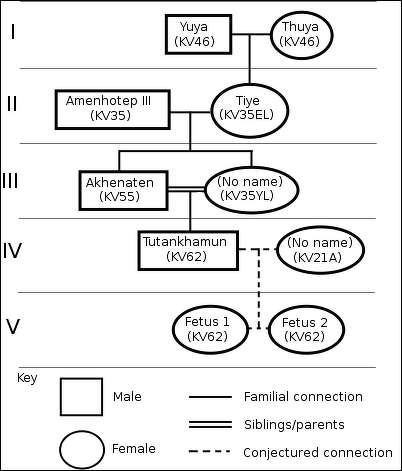

Tutankhamun's (King Tut's) probable gene lineage

King Tutankhamun and Royal Incest

All of these maladies are thought to have been the result of inbreeding between his father and mother — his father’s sister. Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic, “In my view...Tutankhamun's health was compromised from the moment he was conceived. His mother and father were full brother and sister. Pharaonic Egypt was not the only society in history to institutionalize royal incest, which can have political advantages. (See "The Risks and Rewards of Royal Incest.") But there can be a dangerous consequence. Married siblings are more likely to pass on twin copies of harmful genes, leaving their children vulnerable to a variety of genetic defects. Tutankhamun's malformed foot may have been one such flaw. We suspect he also had a partially cleft palate, another congenital defect. Perhaps he struggled against others until a severe bout of malaria or a leg broken in an accident added one strain too many to a body that could no longer carry the load. [Source: Zahi Hawass, National Geographic, September 2010]

There may be one other poignant testimony to the legacy of royal incest buried with Tutankhamun in his tomb. While the data are still incomplete, our study suggests that one of the mummified fetuses found there is the daughter of Tutankhamun himself, and the other fetus is probably his child as well. So far we have been able to obtain only partial data for the two female mummies from KV21. One of them, KV21A, may well be the infants' mother and thus, Tutankhamun's wife, Ankhesenamun. We know from history that she was the daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, and thus likely her husband's half sister. Another consequence of inbreeding can be children whose genetic defects do not allow them to be brought to term.

So perhaps this is where the play ends, at least for now: with a young king and his queen trying, but failing, to conceive a living heir for the throne of Egypt. Among the many splendid artifacts buried with Tutankhamun is a small ivory-paneled box, carved with a scene of the royal couple. Tutankhamun is leaning on his cane while his wife holds out to him a bunch of flowers. In this and other depictions, they appear serenely in love. The failure of that love to bear fruit ended not just a family but also a dynasty.

See Separate Article: KING TUTANKHAMUN'S FAMILY: HIS WIFE, DAUGHTERS AND DETERMINING THE IDENTITY OF HIS FATHER AND MOTHER africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024