Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

HAREMS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

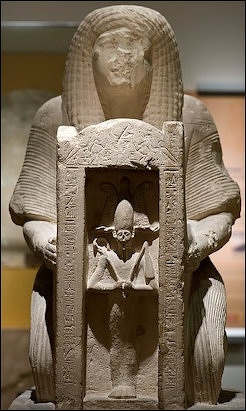

statue of Hormin, director of the harem at Memphis

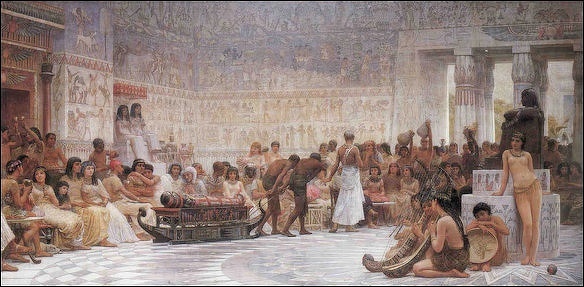

The harem is rarely mentioned in the tombs, yet doubtless at all times it existed as one of the luxuries of the rich. There was a royal house of women. It was the duty of the inmates to cheer Pharaoh by songs, and the ladies of private harems had also to be skilled in similar accomplishments; in the tomb of the courtier T'y, of the fifth dynasty, we see the ladies of the harem dancing and singing before their master." We have also a picture of the harem under the New Kingdom. In a tomb at Tell el Amarna, belonging to the close of the eighteenth dynasty, a distinguished priest called 'Ey has caused his house to be represented. After passing through the servants' offices, the store rooms, the great dining hall, the sleeping room, and the kitchen, at the further end of a piece of ground, the visitor came to two buildings turned back to back and separated by a small garden. These were the women's apartments, 'Ey's harem, inhabited by the women and children. A glance shows us how the inmates were supposed to occupy themselves; they are represented eating, dancing, playing music, or dressing each other's hair; the store rooms behind were evidently full of harps, lutes, mirrors, and boxes for clothes. The possession of such a harem would, of course, be restricted to men of the upper class, for the same reason as it is in the East at the present day — on account of the expense. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Silke Roth of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Germany wrote: “In Egyptological research, the term “harem” (harim) comprises a conglomerate of phenomena, which can be distinguished as: 1) the community of women and children who belonged to the royalhousehold; 2) related institutions, including administrative organizations and personnel; and associated localities and places, like palaces and royal apartments, as well as agricultural land and manufacturing workshops. Key functions of this so-called royal harem can be identified as the residence and stage for the court of the royal women, the place for the upbringing and education of the royal children and favored non-royal children as the future ruling class, the provision of musical performance in courtly life and cult, as well as the supply and provisioning of the royal family. Related Egyptian terms include ipet (from Dynasty 1 onwards), khenere(t) (from the Old Kingdom), and per kheneret (New Kingdom). The compounds ipet nesut and kheneret (en) nesut, commonly “royal harem,” are attested as early as the Old Kingdom. Only a few sources testify to the existence of the royal harem after the 20th Dynasty. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“In ancient Egypt, polygamy was basically restricted to the ruler and his family. Therefore, it is only possible to speak of a “harem” for the royal women and their social circle as well as the related institutions and localities. Given the primary meaning of the harem in the oriental-Islamic cultural spheres and especially the Ottoman example, however, the associated terminology is only limitedly applicable to the so-called harem of the Egyptian king. Nevertheless, both Ottoman and Egyptian harems were centrally involved in raising and educating the future ruler and, more generally, the future inner elite group.

The term “harem” generally describes a cultural phenomenon that is primarily known from oriental-Islamic cultural spheres, where it is still attested. It denotes a very protected part of the house or palace sphere in which the female family members and younger children of a ruler/potentate as well as their servants live separated from the public (Turkish haram from Arabic Harâm, “forbidden,” “inviolable”).

“The imperial harem of the Ottoman sultan (sixteenth to seventeenth century CE), whose everyday life and hierarchical order is known from contemporary descriptions, is the paradigm for the western notion of the harem. The sultan’s mother, who held the highest rank, lived there with up to four of the ruler’s wives; the mother of the oldest son held a special position as principle wife. In addition, the unmarried sisters and daughters of the sultan, his younger sons, concubines, and numerous female servants were members of the harem. Eunuchs acted as intermediaries to the outside world. An important function of the female-dominated imperial harem that resided in secluded rooms of the palace was the education of future female leaders at court. The young men were educated in the male harem, which was constituted in the most inner and inaccessible court of the sultan’s palace around the person of the ruler.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Harem Conspiracy: The Murder of Ramessess III” by Susan Redford (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt: A Genealogical Sourcebook of the Pharaohs” Amazon.com;

”Private Lives of the Pharaohs: Unlocking the Secrets of Egyptian Royalty” by Joyce Tyldesley (2001) Amazon.com;

“Ceremonies of Love Wedding Traditions in Ancient Egypt” by Oriental Publishing (2024) Amazon.com;

“In Bed with the Ancient Egyptians” by Charlotte Booth (2019) Amazon.com;

“24 Hours in Ancient Egypt: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Donald P. Ryan (2018) Amazon.com;

“Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt” by Carolyn Graves-Brown (2010) Amazon.com;

“Daughters of Isis: Women of Ancient Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesley (1994) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Polygamy in Ancient Egypt

Polygamy was quite the exception, we rarely find two wives ruling in a house at the same time; there are, however, a few instances at different periods. Amony, the “great man of the south," who probably died at the beginning of the reign of Amenemhat II., had two wives. One Nebet may have been his niece; she bore him two sons and five daughters; by the other, Hnut, he had certainly three daughters and one son. A curious circumstance shows us that the two wives were friends, for the lady Nebet-sochet-entRe' called her second daughter Hnut, and the lady Hnut carried her courtesy so far as to name all her three daughters Nebet. We meet with the same custom a century later, and indeed, as it appears, in a lower class. One of the thieves of the royal tombs possessed two wives at the same time, the “lady Taruru and the lady Tasuey, his other second wife." [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

In Ancient Egypt, polygamy appears to have existed almost exclusively in royal families and was not practiced by ordinary people if for no other reason few could afford it. i Jaana Toivari-Viitala wrote: “Men could choose for themselves more than one wife, as there exists some evidence that polygamy was practiced from the Old Kingdom onward (if not even before) also outside the royal family, where pharaoh as a rule had a great number of spouses. However, it is not always possible to ascertain with certainty whether one is faced with evidence of polygamy or serial monogamy, where a second wife is taken only after a first one has died. On the whole, it seems that polygamy was not a very common practice outside the royal family. Cases where wives would have several husbands, i.e., polyandry, are unattested.” [Source: Jaana Toivari-Viitala, University of Helsinki, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

Silke Roth of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Germany wrote: “In ancient Egypt, polygamy was basically restricted to the ruler and his family. Therefore, it is only possible to speak of a “harem” for the royal women and their social circle as well as the related institutions and localities. Given the primary meaning of the harem in the oriental-Islamic cultural spheres and especially the Ottoman example, however, the associated terminology is only limitedly applicable to the so-called harem of the Egyptian king. Nevertheless, both Ottoman and Egyptian harems were centrally involved in raising and educating the future ruler and, more generally, the future inner elite group. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“The importance of securing the line of succession and also of marriage policies for maintenance and extension of social and political networks explains why numerous, sometimes concurrent, wives can be assigned to Egyptian kings. However, since there are only few, controversial records documenting multiple marriages of non-royal people, one must assume that polygamy—and thus the harem—was basically restricted to the ruler and his family.”

Ancient Egyptian Royals with Two Wives

Royal double marriages frequently occur. Ramses II is perhaps the most famous case. He two great “royal consorts," Nefertari and Istnofret, and when he concluded his treaty with the Cheta king, he brought the daughter ot that monarch also home to Egypt as his wife. Political reasons doubtless led to this third marriage; the union with the Princess Ra'-ma'-uer-nofru was the seal of the bond of friendship with her father, and the Pharaoh could give no lower place to the daughter of his mighty neighbour than that of his legal wife. Similar motives also probably led to double marriages amongst private individuals; as we have seen above, many daughters of rich men in Egypt possessed valuable rights of inheritance in their father's property. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

See Separate Article: RAMSES II'S FAMILY, QUEENS AND CHILDREN africame.factsanddetails.com

The history of one of the nomarch families of Beni Hasan gives us a case in point. Chnemhotep, son of Neher'e, with whom we had so much to do in the previous chapter, owed the possession of the Nome of the Gazelle to the fortunate marriage of his father with the heiress of the prince of that house. In order to secure the same good fortune for his children, he married Chety, the heiress of the Nome of the Jackal, and, in fact, through this marriage, his son, Nacht, succeeded later to this province. But though Chety was treated with all the respect due to her high rank as his “beloved wife," and as “lady of the house," and though her three sons alone were called the “great legitimate sons of the prince," yet the love of Chnemhotep sterns previously to have been bestowed upon a lady of his household, the “mistress of the treasury, T'atet."

Contrary to former custom, Chnemhotep caused this lady and her two sons, Neher'e and Chnemhotep, the “sons of the prince," to be represented in his tomb, immediately behind his official family. She also accompanies him in his sporting expeditions, though she sits behind Chety, and docs not wear as beautiful a necklet as the legitimate wife. At the funeral festival of the same Chnemhotep, we meet with Chety and T'atet in a covered boat with the “children of the prince and the women," guarded by two old servants of the princely court.-'' There is no doubt that these ivomcii belong to the harem of the prince, to the “house of the secluded," as they were wont to say.

Function and Role of the Royal Harem

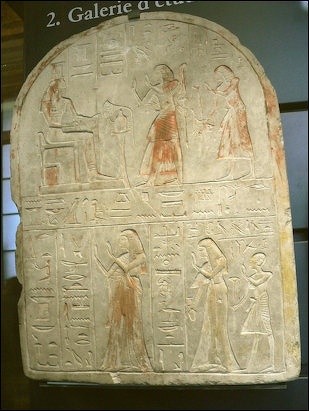

Stela with Ramses II's harem chief Nefertmut

Silke Roth of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz wrote: “The following essential functions can be associated with the social groups, institutions, and localities connected with the harem of the Egyptian king: 1) residence and stage for the court of the royal women, 2) upbringing and education of royal children and favored non- royal children as the future ruling class, 3) musical-artistic accompaniment of courtly life and performance of cult, and 4) supply and provisioning of the royal family. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“Hence, the significance of the royal harem was far beyond the scope of controlling the ruler’s sexual activity and its outcome (cf. Peirce 1993: 3 for the Ottoman harem). Comparable to the royal court, which can be defined as the monarch’s “extended house,” the royal harem played an important role as the “extended family and household” of the ruler as local-factual, social, economic, and ruling institution. A formal affiliation with this extended family allowed individuals the opportunity to support or obstruct political interests and their exponents, and thus offered the possibility of participating in political power.”

A “key function of the harem was the upbringing of royal and elite children. From the Old Kingdom on, a pr mna(t), a “house of education” or “house of the nursery,” is attested as place of learning and from the Middle Kingdom a kAp. The latter can be identified as part of the royal private quarters or the jpt nswt. It is possible that a number of kAp existed, which were assigned to particular royal children. 4bAw nswt, “instructors of the king,” and mna(t) nswt, “tutors” or “wet nurses of the king” were responsible for raising and educating the royal children. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“The sons and daughters of distinguished officials could be raised together with royal children, thus creating a close personal bond between the future ruling class and the successor to the throne. Later in their careers they bore titles such as sbAtj nswt or sDtj(t) nswt, “foster son/daughter of the king”; Xrd(t) n kAp, “child of the kAp”; and sn(t) mna n nb tAwj, “foster brother/sister of the Lord of the Two Lands”.”

“Divine Harems” and “Harems” of the Egyptian King

Silke Roth of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz wrote: “The so-called harem of the Egyptian king does not fulfill the two main criteria of the Ottoman paradigm: neither is there evidence that all women and children were gathered at one location nor that they were cut off from public life. Properly speaking, the harem of the Egyptian king comprised a conglomerate of phenomena, which can be distinguished as follows: 1) the women and children who belonged to the royal household, particularly the queens and “harem women,” princes and princesses, as well as favored non-royal children of both sexes, who were educated at the royal court; 2) related institutions, including administrative organizations and personnel; and 3) associated localities and places, like palaces and royal apartments, as well as agricultural land and manufacturing workshops. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“As more or less comprehensive terms for these groups of people, institutions, and localities, jpt was used from the 1st Dynasty on and—closely related to it—xnr(t) from the Old Kingdom; in the New Kingdom, pr xnrt was also used. These terms are usually translated as “harem” and are evident especially in titles and administrative documents. In the context of administrative texts, it seems that jpt nswt as term for an administrative unit was replaced by (pr) xnrt in the New Kingdom and then is primarily used in titles. The obvious increase in sources for administrative officials, including the range of titles, indicates the expansion of the royal harem from the 18th Dynasty onwards; there are, however, few records after the 20th Dynasty.

In addition to the royal xnr(t), xnr(t)- collectives for male and female gods are attested from the Old Kingdom and are clearly associated with music and dance in the temple cult. These xnr(t) can be identified as the “musical corps” of the respective gods— not as their “harem”—and are therefore not treated in this article (for general comments, see Müller 1977: 815; Naguib 1990: esp. 188 - 207; for the temple of Luxor as jpt rsjt, “southern sanctuary/shrine” of Amun of Karnak—and not his “southern harem”—see, for example, Bell 1998: footnote 2; and Naguib 1990: 193). The prominent role of some royal women in these collectives as “great one of the xnr(t) of (god) NN” is discussed below (see Women in the Harem).”

Royal Women in the Harem of the Egyptian King

Silke Roth of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz wrote:“The importance of securing the line of succession and also of marriage policies for maintenance and extension of social and political networks explains why numerous, sometimes concurrent, wives can be assigned to Egyptian kings. However, since there are only few, controversial records documenting multiple marriages of non-royal people, one must assume that polygamy—and thus the harem—was basically restricted to the ruler and his family. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“Except for their inviolability as an earthly embodiment of goddesses, there is nothing that indicates the female members of the royal family were cut off from wider court and public life. On the contrary, sources reveal that they regularly accompanied the ruler in public appearances, for example, at audiences and festivals. Nevertheless, access to the royal women was without doubt restricted and was controlled by officials and guards. It is also unlikely that all royal wives, daughters, and younger princes lived together in one location. It is more probable that only the principle wife and her children, as well as the king’s mother, resided close to the ruler and accompanied him on some of his travels. The majority of the secondary wives and their entourage seem to have resided in separate palaces in the main residence or in so-called “harem palaces” throughout the country. This situation may apply for most of the numerous daughters of foreign rulers who joined the harem within the framework of the diplomatic marriages and who usually held the rank of subsidiary wives . A clear exception is Maatheru Neferura, a daughter of the Hittite king Hattusili III, who was appointed “great wife of the king” of Ramesses II and was “installed” in the royal palace, “following the sovereign everyday”.

“The current state of research reveals no hierarchies amongst the royal women in the harem except for the differentiation between the principle wife (Hmt nswt wrt, “great wife of the king”) and the king’s secondary wives (“simple” Hmt nswt) that is attested from the 13th Dynasty on. However, interpreting the queen’s title Hnwt Hmwt nbwt, “lady of all women,” as a leading position in the context of the harem could be implied by the single known occurrence of the epithet Hnwt nt Hmwt nswt tmwt, “lady of the royal women altogether” of Meritra Hatshepsut. A hierarchical order can also be proposed for the so-called harem of Mentuhotep II, which fulfilled a purely cultic function. In all probability, there existed a “natural” ranking based on the seniority principle. But this does not seem to have been of major importance since the significance of royal mother and king’s wife varied or changed in any given case or according to the development of the ideology of queenship. For example, royal mothers did not automatically hold the highest rank amongst women at court, as seen in the cases of the young Thutmose III and Siptah, for whom queen dowagers Hatshepsut and Tauseret respectively functioned as regents. The mothers of these kings, attested in sources in marginal positions, can thus be considered subsidiary wives.

“Although the women of the royal family are by definition the most important members of the royal harem, there are relatively few sources that indicate a direct connection between them and the institutions identified as harems, jpt nswt and (pr) xnr(t). An example is the 6th Dynasty biography of Weni that mentions a trial against the royal wife m jpt nswt, which substantiated the identification of jpt nswt as “royal harem”. Other sources reveal that royal women had their own jpt nswt or xnr(t) at their disposal: Sinuhe served in the jpt nswt jrjt-pat wrt Hswt Hmt nswt, the “jpt nswt of the one who belongs to the Pat, great one of favor, and wife of the king” Neferu. A jpt nswt n Hmt nswt wrt is also attested for Tiy and Nefertiti in the 18th Dynasty. The Mittani princess Giluhepa is accompanied on her way to the court of Amenhotep III by the “(female) elite of her xnr(t)-women”. A related phenomenon is the jpt nswt of the god’s wives of the 19th - 21st Dynasties.

“According to the spelling of the collective terms jpt and xnrt with female determinatives, the people associated with these institutions were primarily women. Apparently the queens outranked these “harem women.” The inscription on a stela of Piankhy lists the royal consorts before the jpt nswt, the “women of the royal jpt,” who, for their part, rank higher than the royal daughters and sisters. In the records of the harem conspiracy against Ramesses III, the queen is also named before the “women of the pr xnrt”.”

Harem Women in the Harem of the Egyptian King

Silke Roth wrote: “The xnr(t) nswt, the “xnrt-women of the king,” are attested at the latest in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.). In sources from the New Kingdom that can clearly be associated with the royal (pr) xnr(t), the group of women usually appears as xnrt or, for example, as Hmwt pr xnr(t), “women of the pr xnrt,” in the “harem conspiracy” against Ramesses III. Since xnr(t) is consistently used as collective term for mostly female singers and dancers in cult and ritual performances from the Old Kingdom onwards, the primary meaning of the royal (pr) xnrt and its members can be found in the musical-artistic accompaniment of courtly life and the Staatskult. This assumption is substantiated by other sources: a jmjt-rA xnr n nswt, “(female) overseer of the xnr of the king” Neferesres, who was associated with the jpt nswt, bears the title of “(female) overseer of the dancers” and “(female) overseer of all pleasant enjoyments of the king”. An inscription in the tomb of the overseer of the jpt nswt Iha describes him as “one who conducts the xnr(t) women…who has access to the secret place, who sees the dance in the private quarters”. Reliefs in non-royal tombs at Amarna indicate that a separate wing of the royal palace was inhabited by women who were employed as, for example, musicians. They may be identified as xnrt-women. As the highest- ranking members of this musical-artistic corps, royal women were given a special function in the cult of the gods from the New Kingdom on. This is illustrated in the title wrt xnrt NN, “great one of the xnrt of (god) NN”, and also through representations of the queen, for example, as leader of the “songstresses of Amun” during the Festival of Opet. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“Nevertheless, some scholars still consider xnr(t) as a direct lexical derivation of the root xnr/xnj, “to lock up,” and translate the term in the oriental-Islamic sense of harem, e.g., “the secluded ones,” “house of seclusion.” However, for the Middle Kingdom it is possible to recognize a “separate” locality, xnrt, which was connected with the state- operated production of textiles by women that evidently also took place in the environment of the so-called “harem palace” in Medinet Kom Ghurab (see below).

“The women in the immediate vicinity of the king were also joined by the nfrwt (n aH), “the beautiful ones (of the palace),” next to whom the mrwt nswt, “the beloved ones of the king,” are listed in one text: the “overseer of the precious ointments” Khety is “one who gives veils to the beautiful ones and ornaments to the beloved ones of the king”. The nfrw can be identified as the young girls in the harem, who apparently had the task of entertaining the ruler. In Papyrus Westcar “all of the beautiful ones from the interior of (the) palace,” clad only in nets, rowed king Sneferu across the palace lake. The newly established “women’s house” of the crown prince Ramesses (II) is provided with “jpt nswt-women in the style of the beautiful ones of the palace”.

“In a source from the Middle Kingdom, a group of Xkrwt-women, “ornamented ones,” is mentioned in connection with the royal jpt and the xnrt-women at the royal court: the overseer of the jpt nswt Iha “who brings the xnr(t)-women” is also “one who locks up the ornamented ones”. Are these “ornamented ones” the xnr(t)-women dressed in their valuable robes? This may be suggested by the titles jmj-rA Xkr nswt n Hswt nswt “overseer of the king’s regalia of the royal songstresses” and xntj Xkr n jbAw, “foremost one of the regalia of the dancers”. However, the numerous women with the honorary title Xkrt nswt, “ornamented one of the king,” are not—as once assumed—to be identified as the royal subsidiary wives or concubines, who were “passed on” to distinguished officials once their career in the harem had ended. In fact, they seem to have been court women from every—and also the lower—social class, and only a few were enlisted in the harem or had the rank of a royal wife. By contrast, Lana Troy suggests that the Xkrwt nswt were high ranking court women and “prominent members” of the (pr) xnr(t), who, alongside the nfrwt, “the beautiful ones,” were responsible for music during the performance of the cult. However, Danijela Stefanović doubts any connection between the Xkrwt nswt and the royal court from the late Middle Kingdom onwards.

“A few scenes show the king in intimate contact with his wives or “harem women,” although one must note that it is likely these had a primarily ritual meaning connected with the regeneration and reincarnation of the king. For example, Sahura and Mentuhotep II are depicted embracing their wives in the context of their funerary temples. In a scene inside the High Gate of Medinet Habu, Ramesses III is shown being cared for by young girls and entertained with games. They are captioned once as msw nswt, “royal children,” which suggests that the younger royal daughters also belonged to the “beautiful ones of the palace”.”

an Egyptian feast by Edwin Long

Management of the Harem in Ancient Egypt

Silke Roth wrote: “The institutions connected with the so-called royal harem were mostly autonomous and had their own estates with agriculture, cattle, and manufacturing workshops (especially weaving centers and mills; for general information). They seem to have been entrusted with the production of fine textiles (“royal linen,” mk-fabric) and served the private households of the royal family. The institutions of the harems had their own (tax) income in the form of food supplies, clothing, and fabrics, but were for their part exempted from taxes. When the king was traveling with his entourage, this “traveling harem” was supplied by local institutions. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“A comprehensive staff of officials was entrusted with managing the institutions of the harem. A aA jpt and a wr jpt nswt, “great one of the jpt (nswt),” are attested from the earliest periods. From the Old Kingdom on, the jmj-rA jpt nswt, “overseer of the jpt nswt,” held the highest office . He held a position of exceptional trust, for example, as one “privy to the secret” and “overseer of the sealed goods”. His deputy was the jdnw n jmj-rA jpt nswt or jdnw n pr xnrt (New Kingdom). In the harem administration in the New Kingdom, the rwD n (pr) xnrt, “inspector of the (pr) xnrt,” is well attested. Scribes were engaged in the institutions of the harem and their departments, for example, as sS jpt nswt (from the Middle Kingdom on), sS nswt n pr xnrt, and sS n pr-HD n pr xnrt (New Kingdom). Variations of the titles specified where the officials were located, for example, in the Middle Kingdom at el-Lisht and in the New Kingdom at Kom Medinet Ghurab, Memphis, and Grgt-WAst.” “As the place for raising and educating the heir to the throne and the future ruling class, the harem was repeatedly the origin of political intrigues. These “harem conspiracies,” which are attested for the time of Pepy I, Amenemhat I, and Ramesses III, aimed at murdering the king and usurping the throne. It is quite likely that the harem was involved in arranging national and international diplomatic marriages for the Egyptian court. In the framework of international diplomacy in the New Kingdom, the courts of the foreign royal wives acted as contact points for delegations from their countries and fulfilled the role of permanent diplomatic missions at the Egyptian royal court.”

Places Associated with Harems

Silke Roth wrote: “The only sources prior to the New Kingdom are inscriptions that can be interpreted in relation to architectural structures and locations associated with the royal harem. From Predynastic times the associated hieroglyphs depict a building or the outlines of a building. In the biography of Weni, the jpt nswt is a part of the palace or the royal private quarters in which the queen resided. P. Boulaq 18 from the 13th Dynasty illustrates that the kAp was also located in the private quarters of the royal palace. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“The archaeological evidence, including reliefs, of the New Kingdom illustrates that the buildings of the harem were not only a part of the larger palace complex but were also separate from the royal palace and independent buildings of their own. The so-called “harem palace” of Kom Medinet Ghurab at the entrance to the Fayum formed the center of a city with associated cemeteries (18th - 20th Dynasty Digital Egypt for Universities; the Gurob Harem Palace Project). It comprised two long parallel building complexes within an enclosure wall that can be identified as a residential palace with associated economic area. Magazines and a small temple (19th Dynasty) complete the ensemble. The complex can be identified as the pr xnr Mr-wr or pr xnr S, “pr xnr of Merwer” or “of Shi,” attested in local titles of officials and administrative texts, which was adjoined by an extensive agricultural estate, cattle, and weaving centers. Finds from pits in which furniture and personal effects were burned are reminiscent of a Hittite custom and may indicate that foreign women resided in the harem palace.

“The North Palace of Malqata features a double structure similar to that of the Ghurab ensemble, which can thus be identified as a harem palace that stood in close proximity to the so-called King’s Palace. In fact, a representation in the Theban tomb of Neferhotep shows the palace of the royal principal wife located directly next to the main palace, which thus probably represents the palace complex of Malqata, datable to the reign of Ay. Moreover, a number of suites in the King’s Palace at Malqata can be identified as the living quarters of royal women.

“The women’s quarters depicted in the tombs of the officials at Amarna apparently lay inside the residential palace. However, their identification as the quarters in the Great Palace of Amarna termed the “northern” and “southern harem” is now questionable as a result of the latest research on the fragments of wall paintings found there.

“New research on palace architecture by Kate Spence focuses on aspects of the king’s presentation and access to his physical presence in this context. According to her approach, the palace structures she defines as semi-axial, which feature difficult access routes, are primarily associated with royal women. They usually comprise smaller rooms or suites that are grouped along a hall or a court with throne dais or another manifestation of the king’s presence. According to Spence, these structures establish and express the subordinate and ranked relationship of individuals to the ruler, which can most likely be associated with royal women or close family members. The most obvious example is the King’s Palace at Malqata; other candidates include the North Palace and Great Palace at Amarna. The ritual palaces of the New Kingdom temple complexes, which display the main structures of a residential palace in simplified form, also apparently included rooms in which royal women resided when they accompanied the ruler in performing the cult.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024