Home | Category: New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut)

RAMSES II'S FAMILY

Ramses the Great, also known as Ramses II, was perhaps the greatest of all the Egyptian pharaohs. He became Pharaoh in 1279 B.C. when he was in his twenties and the pyramids were already 1,300 years old. He ruled ancient Egypt for 67 years during the golden age of the civilization. He raised more temples, obelisks and colossal monuments that any other Pharaoh and ruled an empire that stretched from present-day Libya and Sudan to Iraq and Turkey. The Bible refers to him simply as "Pharaoh." [Source: Rick Gore, National Geographic, April 1991 [♣]

Maite Mascort wrote in National Geographic History: Ramses’ family came to power as outsiders. They were northerners hailing from the Nile Delta and rose through military service, rather than southerners rising from elite circles in Thebes. [Source: Maite Mascort, National Geographic History, February 16, 2023]

During the 18th Dynasty most rulers believed themselves to be the progeny of a divine union between their mothers and the god Amun-Re, as claimed by Queen Hatshepsut and Pharaoh Amenhotep III, among others. But Ramses II and his successors could not claim such ancestry — because their paternal line did not descend from royalty. Ramses II’s grandfather Paramessu had been a vizier under Horemheb, the last pharaoh of the 18th dynasty.Taking the name Ramses I, Paramessu ruled a few years before his son took the throne as Seti I. Although Ramses I is technically the founder of the 19th dynasty, some consider Seti I — Ramses II’s father — the first real Ramesside king.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

"Ramesses II, Egypt's Ultimate Pharaoh" by Peter Brand Amazon.com;

“Pharaoh Triumphant. The Life and Times of Ramesses II” by Kenneth Kitchen (1990) Amazon.com;

”Pharaoh Seti I: Father of Egyptian Greatness” by Nicky Nielsen (2020) Amazon.com;

“Ramesses: Egypt's Greatest Pharaoh” by Joyce Tyldesley (2001) Amazon.com;

“Ramesses the Great: Egypt's King of Kings” by Toby Wilkinson Amazon.com;

“The Eastern Mediterranean in the Age of Ramesses II” by Marc Van De Mieroop Amazon.com;

“Qadesh 1300 BC: Clash of the Warrior Kings” (1993) by Mark Healy Amazon.com;

“Warfare in New Kingdom Egypt” by Paul Elliott (2017) Amazon.com;

“War in Ancient Egypt: The New Kingdom” by Anthony J. Spalinger (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Mysteries of Abu Simbel: Ramesses II and the Temples of the Rising Sun” by Zahi Hawass (2001) Amazon.com;

“Colossal Statue of Ramesses II” by Anna Garnett (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Temple of Ramesses II in Abydos: Volume 1, Wall Scenes - Part 1, Exterior Walls and Courts & Part 2, Chapels and First Pylon (2 volumes)” by Sameh Iskander and Ogden Goelet (2015) Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom" by Joyce Tyldesley (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume III: From the Hyksos to the Late Second Millennium BC” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

"The New Kingdom" by Wilbur Smith, Novel (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Late New Kingdom in Egypt (c. 1300–664 BC) A Genealogical and Chronological Investigation (Oxbow Classics in Egyptology) by M. L. Bierbrier (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Temples, Tombs, and Hieroglyphs: A Popular History of Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz (1978, 2009) Amazon.com;

Ramses I and Seti I— Ramses II's Grandfather and Father

Ramses I — Ramses II's grandfather — was a commoner named Pramesse and leading bureaucrat when Pharaoh Horemheb died with no heir. He was the first pharaoh of Dynasty XIX, which lasted only 16 months.

John Ray of Cambridge University wrote: Ramses I was "a solid figure, but essentially a provincial bureaucrat who had had greatness thrust upon him. This was not inspirational. When Ramesses II turned his attention to recent history, he would have seen the upheavals of the Amarna period, an episode which needed to be purged from the record. Before this, however, lay the family of the Tuthmosids, a dynasty which was associated with prosperity, elegance, and the growth of empire. [Source: John Ray, Cambridge University, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Seti I, Ramses I's successor and Ramses II's father, was a "vigorous warrior." He expanded the Egyptian empire to include Cyprus and parts of Mesopotamia. Seti I lives on as one of the best-preserved mummies. His face is on display at the Egyptians Museum. The Egyptologist Methew Addams told the New York Times, “people have been influenced by that face in their interpretation of Seti as having been a good, wise king, We are really projecting our own esthetic on him.”

Seti I took his son Ramses II on military campaigns to Libya when he was 14 and later to Syria to battle the Hittites. Seti I's reign saw military success as well as achieving one of the high points of Egyptian art, marked by sensitivity, balance and restraint. These were the hard acts which it was Ramesses' destiny to follow, and one way of doing this would be to upstage the past by ostentation, thereby eclipsing it. Ramesses II was well suited to this kind of role, and the gods gave him a reign of 67 years in which to perfect his act.

In October 2003, the mummy of a pharaoh was returned too Egypt by the Michael Carlos Museum at Atlanta’s Emory University. Much fanfare was made bout the return of the mummy, which some believe in Ramses I based on the way the arms are crossed high over the chest, as was the custom with royal mummies in Ramses time and the resembled of face to faces of Seti I. Ramses II and Ramses VII. The mummy thought to be Ramses I was sold by dealers in the 19th century and ended yo in the Niagra Falls museum where at was displayed next to a two-headed and barrels used by daredevil go over the falls and were handed over to the museum at Emory after the Niagra museum was closed.

Ramses II's Wives

Ramses II had eight wives — including his younger sister and three daughters — and numerous concubines, which included several Hittite princesses. Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen said: “If he got tired of hunting and shooting he could wander through the garden and blow a kiss at one of the ladies." In reliefs Ramses II is often pictured with a big dick and strong erection.

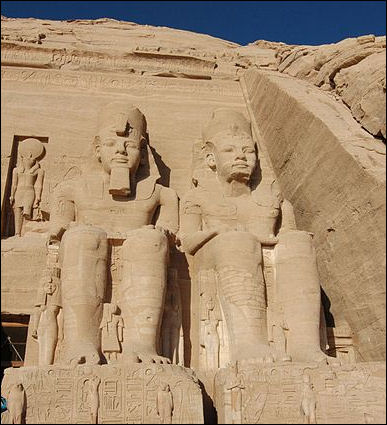

Nefertari and Ramses II at Abu Simbel While Seti was still Pharaoh he selected a harem for his son. Ramses principal wife, the beautiful Nefertari, quickly produced a son. And not long afterwards his second favorite wife, Isntnofret, delivered another. More and more children followed. "Nefertari had the looks," Kitchen told National Geographic, "He was obviously proud of her, showing her off all the time. But I think Istnofert had the brains. It was her offspring that wielded the most power as Ramses aged."♣

Maite Mascort wrote in National Geographic History: One of the most striking aspects of Ramses II’s story is the women who surrounded him: great royal wives and concubines, secondary wives and daughters, whom he sometimes “married,” for political show or perhaps for real. He produced an extraordinary number of sons and daughters: Some records say as many as a hundred. Because of his long reign, many of his children predeceased him. [Source: Maite Mascort, National Geographic History, February 16, 2023]

Out of all of his wives, only two were known to have had prominent roles: Nefertari and Isetnofret, the first two named great royal wives. While the former figures prominently in Egyptian sources and countless representations of her exist, little is known of the latter, almost as if Ramses wanted her hidden. It is only natural to wonder about the reasons for such unequal treatment.

When he became co-regent with his father, Seti I, Ramses II received a palace in Memphis, just south of the Nile Delta, and a large harem, including the first two great royal wives. The origins of Nefertari and Isetnofret are unknown, but that has not prevented the wildest of speculation about them. Everything suggests that Nefertari was Ramses II’s favorite wife. Her beauty is attested to in the statues and paintings in her tomb in the Valley of the Queens.

Nefertari, Ramses II's Principal Queen

Nefertari was Ramses first and favorite wife. He raised many statues to honor her. She often appeared with him at state and religious ceremonies. She may have traveled with Ramses on diplomatic missions and given him important advise. It is Nefertari — of equal size — who sits side by side with Ramses at Abu Simbel and Luxor. A dedication for Nefertari's statue at Abu Simbel reads, "Nefertari, for whose sake her very sun does shine!" In contrast, wives of other pharaohs were usually depicted as diminutive figures at the feet of their husbands.

Little is known about Nefertari's early life. She is believed to have come from southern Egypt and may have been related to Queen Nefertiti. Nefertari bore Ramses five or seven children before she died in 1255 B.C. When Nefertari died during Year 24 of Ramses II’s reign the Pharaoh produced the most beautiful tomb yet discovered in the Valley of the Queens. More or less intact today, the tomb features paintings of Nefertari in a sexy linen gown.

Nefertari took part in official events alongside Ramses. She is shown celebrating his coronation, in festivities of the god Min, and in Nebunenef’s enthronement as High Priest of Amun. Her diplomacy culminated in a peace treaty between Ramses and the Hittites several years after the Battle of Kadesh (1274 B.C.) had resulted in a stalemate between the two powers.

Images and Monuments of Nefertari

Maite Mascort wrote in National Geographic History: Ramses II showed a clear predilection for Nefertari, devotion worthy of a great love story. When he built the great temple of Abu Simbel, he made sure that Nefertari, then deceased, was on the facade, next to Tuya, his mother. In this temple, Nefertari is transformed into Sopdet, the star Sirius, whose appearance presaged the Nile’s annual flooding. Farther north, another smaller temple dug into rock is dedicated to Nefertari herself. There she is identified with the goddess Hathor. Carved into its facade is a tribute, “Nefertari, she for whom the sun shines.” [Source: Maite Mascort, National Geographic History, February 16, 2023]

One painting of Nefertari her shows her with cobras for earnings. In another Ramses callers her the "Possessor of charm, sweetness, and love." Even so, Maite Mascort wrote in National Geographic History: It is uncertain what she actually looked like, since some images raise doubts about who is depicted. For example, in Karnak, a small statue of Nefetari stands at the foot of a colossus representing Ramses II, her husband. The colossus was later usurped by Pharaoh Pinedjem I, who had his name inscribed on it, and the features of both figures may have been modified. Was only the name changed? Is that beautiful face still Nefertari’s? Egyptologists believe so.

John Ray of Cambridge University wrote: “Nefertari is best known for her exquisitely decorated tomb in the Valley of the Queens at Luxor... one of the finest sights in Egypt. Nefertari owed her place in the king's affections partly to her charms, but also to the fact that she was the mother of several princes and princesses, including the eldest son and heir, who was given the snappy name Amenhiwenimmef, 'Amun is on his right hand'. Nefertari seems to have died before the thirtieth year of her husband's reign. [Source: John Ray, Cambridge University, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Tomb of Nefertari

The Tomb of Nefertari (in the Valley of the Queens near Luxor) is the most beautiful tomb in the Valley of the Queens or the Valley of the Kings and one of the most extraordinary works of art in the world. Over 3,200 year old, it is in amazingly good condition for its age and features extraordinary wall murals, painted with vivid colors, great skill and a wonderful sensitivity for detail.

Regarded as a close representation of the "House of Eternity," the tomb of Queen Nefertari is composed of seven chambers—a hall, side chambers and rooms connected by a staircase—and features paintings made on engraved outlines of humans, deities, animals, magic objects, scenes of everyday life and symbols such as ibis heads, scarabs, papyrus, lotuses, vultures and cobras.

On being inside the tomb, Marlise Simons wrote in the New York Times,"The effect is rich like a house hung with jewelry, and it has an intensity that appeals strongly to modern eyes. But what makes these galleries just as moving is the fine detail of the images, their exquisitely carved relief and the gestures of endearment that give the figures life...There is are sweetness and intimacy that makes contact across the centuries seem somehow possible."

See Separate Article: TOMB OF NEFERTARI: CHAMBERS, PAINTINGS, MEANING OF THE ART africame.factsanddetails.com

Isinofre: Ramses II's Other Principal Wife

Maite Mascort wrote in National Geographic History: Was Isetnofret the forgotten one? So it seems. Until Nefertari died, around year 26 of Ramses II’s reign, Isetnofret’s likeness did not appear in the many temples the king built in Nubia, nor in those in Karnak and Luxor, where Nefertari is often portrayed. Isetnofret was finally represented in some temples for her connection with her children. Nefertari’s image may be seen in more places, but it was Isetnofret who bore her husband the two children closest to his heart. [Source: Maite Mascort, National Geographic History, February 16, 2023]

John Ray of Cambridge University wrote: “The second principal wife is Isinofre, who is less well known. The influence of this queen is more detectable in the north of the country. She was a contemporary of her rival, and she could boast that she had borne the king his second son, diplomatically named Ramesses, and a favourite daughter, who was given the Canaanite name Bintanath, 'Daughter of the goddess Anath'. [Source: John Ray, Cambridge University, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Isinofre was also the mother of the fourth in line to the throne,a prince named Khaemwise, who pursued a career in the priesthood of Memphis, and devoted himself to the study of hieroglyphs and antiquities. He also designed the Serapeum, the catacomb for the sacred Apis bulls in the desert at Saqqara. As a result of his interests and activities, Khaemwise has been described as the first Egyptologist in history. |::|

Ramses II's Children

Ramses II fathered more than 100 children, including 52 known sons. According to some accounts he sired 162 children. By one count he had 96 sons and 60 daughters, with 200 or more wives and concubines, some of whom were his relatives. According to another reckoning he had 111 sons and 51 daughters.

Ramses II's father started his harem when he was 10. When he ascended to the throne at 25 he had already fathered ten sons and as many daughters. Kitchen said: "Ramses's house must have resounded with the gurgles, yelps and whimpers of each year's crop or bouncing royal babies." At the age of 20, Ramses took of his sons with him to campaign to quell down a minor revolt and lets them take part in a chariot charge. Ramses outlived 12 of his heirs and when he died his 13th son, Merneptah, took the throne in his sixties. Merneptah was a son of an Istnofret.

Maite Mascort wrote in National Geographic History: Of his recognized children, some would play important roles, but only those born to Nefertari and Isetnofret appear on his monuments. In the Nubian temple of Beit el Wali, a young Ramses, then co-regent with his father, Seti I, is shown suppressing a Nubian uprising. The pharaoh’s royal chariot is flanked by two figures identified as Amenherkhepshef, his eldest child with Nefertari, and Khaemwaset, Isetnofret’s son. [Source: Maite Mascort, National Geographic History, February 16, 2023]

Of all Ramses II’s sons, Khaemwaset is believed to have been his favorite. Instead of taking up arms against his elder brother (also named Ramses), Khaemwaset became Grand Master of the Artisans of Ptah, a title in Memphite doctrine equivalent to High Priest of Amun in Thebes. He also restored a number of pyramids in his father’s name. His work is still evident on the pyramid of Unas, from the 5th dynasty.

Khaemwaset also planned and directed the work of the “minor galleries,” the Serapeum at Saqqara, the collective tomb of the Apis, sacred oxen of Memphis. Auguste Mariette’s 1850 excavation of the Serapeum revealed the mummy of a man named Khaemwaset, wearing a golden mask with several ushabtis. It proved uncertain that it was the mummy of Ramses II’s son, and the location of Khaemwaset’s tomb remains unconfirmed. Much evidence suggests that it is in the necropolis of Saqqara.

Daughters of Ramses II

Maite Mascort wrote in National Geographic History: The daughters of Ramses II’s great royal wives also held key positions in his court. In fact, many became great royal wives themselves after marrying their own father. It had become customary for 18th-dynasty pharaohs to marry their daughters. While his great royal wife Tiye was alive, Amenhotep III married their daughter Sitamun. Later, Akhenaten married at least two of the daughters he had with Queen Nefertiti. No one knows if these marriages were consummated or purely ceremonial.

Ramses II appointed several daughters great royal wives after the deaths of Nefertari and Isetnofret. Bintanah (Isetnofret’s firstborn) was followed by Merytamon and Nebettawy (daughters of Nefertari) and Henutmire. In addition to these daughters, other princesses outside the family also bore the title of Great Royal Wife, such as Maathorneferure, daughter of the Hittite king, and another Hittite princess whose name is unknown.

If Khaemwaset was Ramses II’s favorite son, everything points to Bintanath having been his preferred daughter. She was given the titles of not only Great Royal Wife but also Lady of the Two Lands and Sovereign of Upper and Lower Egypt. Bintanath occupies a privileged place on the facade of the temple of Abu Simbel. She and her sister Nebettawy appear on either side of the colossus. Some historians believe Nebettawy’s mother was Isetnofret, but others consider her Nefertari’s daughter.

Tomb of Ramses Sons

On February 2, 1995, American archaeologist Ken Weeks discovered a huge tomb with at least 108 chambers in the Valley of the Kings near Luxor. Archaeologists considered it the most significant discovery in Egyptology since the discovery of King Tut's tomb.

Known officially as KV5 (the 5th tomb discovered in the Valley of the Kings) and located about 100 feet from the tomb of Ramses the Great, the tomb is believed to have been a burial place for many of Ramses the Great' sons.

KV5 is the largest and most complex Egyptian tomb every discovered and the only multiple tomb for pharaoh's children. Inscriptions on the walls mentions two of Ramses' sons, which is what led archaeologists to believed it may be a tomb for his sons.

Describing the sensation of being in the tomb, Douglas Preston wrote in the New Yorker, "Nothing in twenty years of archaeology has prepared me for this great wrecked corridor chiseled out of the living rock, with rows of shattered doorways opening into darkness, and ending in the faceless mummy of Osiris...As I stare at the walls ghostly figures and faint hieroglyphics; animal-headed gods performing mysterious rites. Through doorways I catch a glimpse of more rooms and doorways beyond."

After being the first person to enter one chamber, "I sit up and look around....There is three feet of space between the top of the debris and the ceiling, just enough for me to crawl around...The room is about nine feet square, the walls finely chiseled from the bedrock...In run my fingers along the ancient chisel marks...Their only source of light would have been the dim illumination from wicks burning in a bowl of oil salted to reduce smoke.

Book: “ The Lost Tomb” by Kent R. Weeks (William Morrow & Co.) is the story of the tomb of the children of Ramses II.

Details about the Tomb of Ramses Sons

KV5 has a T-floor plan and is made up of a series of boxcar-like chambers connected by corridors, and ending with a burial vault. There are a number of descending passageways and side chambers and suites and false doors. One of the largest chambers is sixty square feet. It is supported by four huge pillars arranged in four rows.

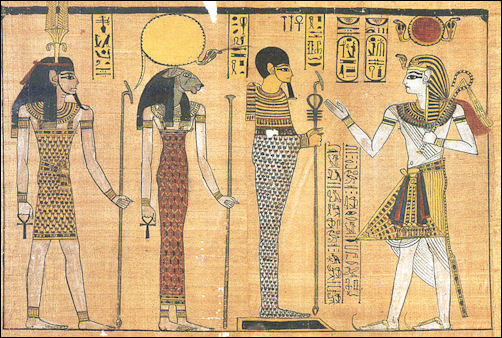

Ramses III and the Memphis gods

There are reliefs that show Ramses presenting various sons to the gods, with the names and tools recorded in hieroglyphics. Objects found include faince jewelry, fragments of furniture, pieces of coffin, humans and animal bones, mummified body parts, chunks of sarcophagi, remains of jars used for mummified organs — all debris left behind by looters.

The purpose of the tomb is a mysterious. Its design is radically different from other ancient Egyptian tombs. The rooms are not believed to have been burial chambers because the doorways are too narrow to admit sarcophagi. Instead they are believed to have been chapels where priest made offerings to the dead sons.

One corridors heads in the direction of the Tomb of Ramses and some scholars speculate that they might be connected. No two tombs are known to be connected. Some scholars believe Ramses's daughters might be buried in the tombs, others say that is unlikely. Archaeologists have found no evidence of Moses or the Exodus.

Merneptah, Ramses II’s Successor, and His Battles Against the Libyans

Merneptah (1213 – 1203 B.C.) was Ramses II’s son and successor. Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “In his last years, Ramses II had allowed the whole of the west side of the Delta to fall into the hands of foreigners, and on the east side the native Egyptians were being rapidly ousted by foreign settlers. His extravagant building projects had damaged the economy of the country and the people were impoverished. Now, through neglect, Egypt was in danger of losing the whole Delta, first to foreign immigrants and then by armed invasion. “This is the situation Ramses’ son, Merneptah, inherited. He spent the first few years of his reign making preparations for the struggle which he knew to be inevitable. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “When Senusret [Ramses II] died, he was succeeded in the kingship (the priests said) by his son Pheros [The King’s list shows no such name. It is probably not a name but a title, Pharaoh]. This king waged no wars, and chanced to become blind, for the following reason: the Nile came down in such a flood as there had never been, rising to a height of thirty feet, and the water that flowed over the fields was roughened by a strong wind; then, it is said, the king was so audacious as to seize a spear and hurl it into the midst of the river eddies. Right after this, he came down with a disease of the eyes, and became blind. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“When he had been blind for ten years, an oracle from the city of Buto declared to him that the term of his punishment was drawing to an end, and that he would regain his sight by washing his eyes with the urine of a woman who had never had intercourse with any man but her own husband. Pheros tried his own wife first; and, as he remained blind, all women, one after another. When he at last recovered his sight, he took all the women whom he had tried, except the one who had made him see again, and gathered them into one town, the one which is now called “Red Clay”; having concentrated them together there, he burnt them and the town; but the woman by whose means he had recovered his sight, he married. Most worthy of mention among the many offerings which he dedicated in all the noteworthy temples for his deliverance from blindness are the two marvellous stone obelisks which he set up in the temple of the Sun. Each of these is made of a single block, and is over one hundred and sixty-six feet high and thirteen feet thick.”

Merneptah’s Battles Against the Libyans

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: For the first time in over 400 years, since the Hyksos invasions that ended the Middle Kingdom, “Egypt was in danger of being overrun. The Libyan chief, Meryawy, had decided to attack and conquer the Delta he was convinced of an easy victory believing the Egyptians to have grown soft. So confident was he that he brought his wife and children and all his possessions with him.The night before the decisive battle Merneptah had a prophetic dream, “His Majesty saw in a dream as if a statue of the god Ptah stood before his Majesty. He said, while holding out a sword to him, ‘Take it and banish fear from thee.” [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

The Merneptah Stele, also known as the Israel Stele or the Victory Stele of Merneptah, is an inscription by Merneptah (reigned 1213–1203 BC); The text is largely an account of Merneptah's victory over the ancient Libyans and their allies, but the last three of the 28 lines deal with a separate campaign in Canaan, then part of Egypt's imperial possessions; It is sometimes referred to as the "Israel Stele" because a majority of scholars translate a set of hieroglyphs in line 27 as "Israel"

“Merneptah had stationed archers in strategic positions, and they poured their arrows into the invading armies. “The bow-men of his Majesty spent six hours of destruction among them, then they were delivered to the sword.” Then when the enemy showed signs of breaking, Merneptah let loose his charioteers among them. He had promised his people that he would bring the enemy “like netted fish on their bellies”, and he fulfilled his promise. His Triumph-Song shows that he regarded the defeat of the Libyans not so much as a great victory but rather as a deliverance. “To Egypt has come great joy. The people speak of the victories which King Merneptah has won against the Tahenu: How beloved is he, our victorious Ruler! How magnified is he among the gods! How fortunate is he, the commanding Lord! Sit down happily and talk, or walk far out on the roads, for now there is no fear in the hearts of the people.”

“The fortresses are abandoned, the wells are reopened; the messengers loiter under the battlements, cool from the sun; the soldiers lie asleep, even the border-scouts go in the fields as they list. The herds of the field need no herdsmen when crossing the fullness of the stream. No more is there the raising of a shout in the night, ‘Stop! Someone is coming! Someone is coming speaking a foreign language!’ Everyone comes and goes with singing, and no longer is heard the sighing lament of men. The towns are settled anew, and the husband man eats of the harvest that he himself sowed. God has turned again towards Egypt, for King Merneptah was born, destined to be her protector.”

The defeat of the Libyans saved Egypt from utter ruin but her economic and political decline continued at a steady pace. The only other record of this time is of a grain shipment to the Hittites to relieve a famine so it seems the treaty between the two peoples continued to hold firm. The rest of the dynasty is torn by political struggles for the throne. These pharaohs were all weaklings and their disputes only served to plunge the country into civil disorder. “The land of Egypt was overthrown. Every man was his own guide, they had no superiors. The land was in chiefships and princedoms, each killed the other among noble and mean.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024