Home | Category: Government, Military and Justice

DUTIES OF THE KINGS OF ANCIENT EGYPT

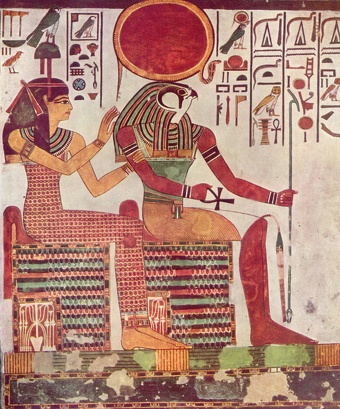

Orisis It is believed that Pharaohs performed many duties and presided over many rituals. Mundane ceremonies are believed to have been performed by his sons. By buildings temples and making offerings the Pharaoh was of continuously renewing the bond the between the people, the Pharaoh and the gods. Officials called “viziers” helped the king govern. The viziers acted as mayors, tax collectors, and judges. Other high officials who served the king included a treasurer and an army commander.

If we may believe what Diodorus tells us of the daily life of the king, we shall find the order of each day most strictly regulated for the Pharaoh. At daybreak the king despatches and answers his letters, he then bathes and robes himself in his state garments and assists at the sacrifice in the temple. There the high priest and the people pray for the god's blessing on the king, and the priest gives him to understand, in a figurative way, what is worthy of praise or blame in his manner of ruling. After this homily the king offers sacrifice, but does not leave the temple until he has listened to the reading from the sacred books on the deeds and the maxims of famous men. His manner of life during the remainder of the day is exactly laid out for him, even as to the times for his walks, or for his frugal meals of goose-flesh, beef, and wine. Everything, Diodorus tells us, is arranged as strictly and reasonably as if “prescribed by a physician." [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The monarch could scarcely fulfil all his religious duties, as well as those of the administration which were expected of him. His cabinet-' formed the center of the government, to which all the chief officials had to “render their account," and to which “truth must ascend. " When reports were concluded, they were laid before the ruler, and special questions were also brought to him for his decision; this was the case, at any rate, in the strained conditions of the time of the New Kingdom.

When thieves were caught, tried, and found guilty, the court was not allowed to pronounce sentence; the report was made to the Pharaoh, who decreed what punishment was to be awarded; when houses were allotted to laborers, the king was importuned about it. In short, there was nothing which might not, under certain circumstances, be brought before the Pharaoh, and if he were not able personally to sift the matter, he was obliged to appoint a delegate '' to take his place. We who know the pleasure the Egyptian scribe took in lawsuits, realise how many reports “the king had daily to read, and how many royal orders he had to give. The monarch had also to journey through the country and examine in person the condition of the buildings, etc. We learn how more than once the king traveled through the desert in order to understand the position of the quarries and of the oases.

The king had of course trustworthy officials to assist him in this work; the chief of these was the T'ate, the “governor," whom we may consider as the leader of the government, and who communicated with the king on state affairs through the “speaker. " “In difficult cases the king summoned his councillors, or (as they were called During the New Kingdom) "his princes, who stand before him," and requested their opinion. The king often appointed his son and heir as co-regent — this was the case under most of the kings of the 12th dynasty. We read that he “appoints him his heir on the throne of the god Qeb; he becomes the great captain of the country of Egypt, and gives orders to the whole country. "

During the New Kingdom, when the army became more powerful, the Pharaohs preferred to be invested with military titles, and were called the generals of their father. They participated at the battles, and were the first to venture up the ladders when a fortress was stormed — at least according to official representations of battles. Those even who devoted themselves to the priestly profession, and who in their old age were high priests, as Meryatum, the pious son of Ramses II, were not excluded in their youth from taking part in the battles. '

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Pharaoh: Art and Power in Ancient Egypt” by Marie Vandenbeusch (2024) Amazon.com;

“Kingship, Power, and Legitimacy in Ancient Egypt: From the Old Kingdom to the Middle Kingdom” by Lisa K. Sabbahy (2004) Amazon.com;

“Judgement of the Pharaoh: Crime and Punishment in Ancient Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesley

Amazon.com;

“The Pharaohs” by Joyce Tyldesley (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt” by Elizabeth Payne (1981) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“The Pharaoh: Life at Court and On Campaign” by Garry J. Shaw (2012) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

”Private Lives of the Pharaohs: Unlocking the Secrets of Egyptian Royalty” by Joyce Tyldesley (2001) Amazon.com;

“Gods Priests & Men” by Alan Lloyd Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Temple Ritual: Performance, Patterns, and Practice” by Katherine Eaton (2013) Amazon.com;

Rituals Performed by the Pharoah

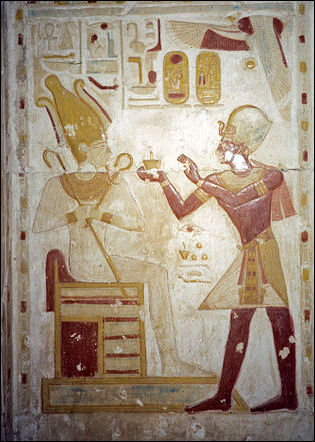

The Egyptian king had always to play a religious part. In the same way as each Egyptian of high standing exercised a kind of priestly office in the temple of his god, so the king was considered the priest of all the gods. Whenever we enter an Egyptian temple, we see the king represented offering his sacrifice to the gods. In most cases this is symbolic of the presents and revenues with which the king endowed the temple, but it is not probable that they would have had these representations if the king had not sometimes ofiiciated there in person. At many festivals {e. g. the above-mentioned festival of the god Min) it is expressly declared in the official style of the inscription, that the chief business of the king is to “give praise to his fathers, the gods of Upper and Lower Egypt, because they give him strength and victory, and a long life of millions of years. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

It was part of the king's work to guide the government and carry on the wars, but in theory his duty towards the gods was still important, Being, in very deed, “the son of Ra, who is enthroned in his heart, whom he loves above all, and who is with him, he is a shining embodiment of the lord of all, created by the gods of Heliopolis. His divine father created him to exalt his glory. Amun himself crowned him on his throne in the Heliopolis of the south, he chose him for the Shepherd of Egypt, and the defender of mankind. " When the gods blessed the country, it was for the sake of the ir son; when after many failures they allowed some undertaking to succeed, it was in answer to the prayers of the ir son. With these ideas what is more natural than that the people should consider the king to be the mediator for his country? He alone with the high priest might enter the Holy of Holies in the temples, he alone might open the doors of the inner sanctuary and “see his father the god. "

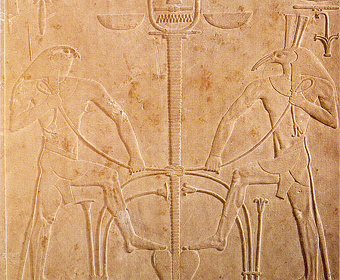

Susan Allen of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The ancient Egyptians regarded their king and the office of kingship as the apex and organizing principle of their society. The king's preeminent task was to preserve the right order of society, also called maat. This included ensuring peace and political stability, performing all necessary religious rituals, seeing to the economic needs of his people, providing justice, and protecting the country from external and internal danger. It has sometimes been said that the ancient Egyptians believed their kings to be divine, but it was the power of kingship, which the king embodied, rather than the individual himself that was divine. The living king was associated with the god Horus and the dead king with the god Osiris, but the ancient Egyptians were well aware that the king was mortal. One of their most ancient rituals was the sed festival, or jubilee, at which the mortal king reaffirmed his fitness to continue as king. [Source: Susan Allen, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

After a pharaoh had been on the throne for 30 years a jubilee was held. From then on another was held every three years. During the celebration, which dates back to original pharaohs, rituals and feasts were held. The king's coronation was re-enacted. To top it all off the pharaoh was supposed to run around a track to demonstrate his fitness. Ramses had 13 jubilees. It is hard to imagine him going for a jog on his last one when he was he was nearly 90.♣

Many of the grandest temples such as Great Temples of Hatshepsut and Temple of Amenhotep III at the Colossi of Memnon were mortuary temples designed as places for people to gather for special religious rites and offerings connected with the cult of the pharaoh it was built for cult to guarantee that he lived on in the afterlife. Rulers often pillaged or remodeled the temples of their successor either to erase his memory or save money on building materials. Smashing statues was a way to disrupt the afterlife of their precursors.

Ritual Smiting and Royal Violence in Ancient Egypt

smiting on the Narmer Palette

Kerry Muhlestein of Brigham Young University wrote: “The language used to describe several sanctioned killings implies that they took place in a ritual context, while other texts are explicit about the ritual nature of the slaying. For example, Senusret I slayed offenders at the temple of Tod, Ramesses III captured and killed Libyans in a ritual context , and Prince Osorkon burned rebels in the temple of Amun at Karnak. In all of these cases ritual language is employed to describe the killings. For example, the text of Osorkon records the punishment of rebels: “Then he struck them down for him, causing them to be carried like goats on the night of the Feast of the Evening Sacrifice in which braziers are lit...like braziers at the going forth of Sothis. Every man was burned with fire at the place of his crime”. [Source: Kerry Muhlestein, Brigham Young University, 2015, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“There is some evidence that the stereotypical smiting scene at times may have been an actual ritual. Undoubtedly Amenhotep II smote captives as part of his coronation ritual. Several late New Kingdom non-royal stelae represent the king smiting prisoners within temple grounds, perhaps indicating that the owner of the stela had witnessed the ritual. Some have disagreed with this interpretati on, such as Ahituv, while others, including myself , have supported Schulman’s claims, showing faults with the arguments of his detractors, such as illustrating that Ahituv was wrong in stating there was no corroborating evid ence for kings actually smiting prisoners, or demonstrating the illogic behind concluding that if Syrian prisoners were spared in the palace, none of them could have been smitten.

“Some texts describing Ramesses III’s dealings with captives can be taken to indicate that he subjected them to ritual smiting, such as when a captive prince and his visiting father engendered distrust in Ramesses and he “came down upon their heads like a mountain of granite”. Moreover, a number of specialized a nd individualized smiting scenes imply that these were based on real events, such as the depiction of a man with a unique physical deformity being struck by the king. While we cannot be sure, it is quite likely that smiting enemies was a royal ritual.”

Pharaohs, the Gods and the Afterlife

The pharaohs were considered to be gods — incarnations of falcon-head Horus, children of the sun god Re. They were descendants of the Amun, regarded as the first Egyptian king, who in turn descended from the sun-god Ra and the falcon god of kingship Horus. Egyptians believed they were given their authority to rule when the world was created.Referred to as the "lord of all the sun disk encircles," the Pharaoh was believed to be one with the universe and the gods and was regarded as an intermediary between the gods and people on earth. Through them the life force was conveyed from the gods to the people. A Pharaoh’s coronation was viewed not as "the making of a god but the revealing of a god." According to the ancient Egyptians, the pharaohs were the link between heaven and the earth and their breath kept the two worlds separate.♣

Each king was of divine birth, for as long as he was acknowledged sovereign, he was considered as the direct descendant of Ra. This belief was not affected by the fact that in course of time the throne passed frequently from one family to another. In early ancient Egypt idea of the divinity of the king was not carried to its final consequences; temples were not erected, nor were sacrifices offered, to the king whilst he dwelt amongst men. These custom appear in the New Kingdom (1570-1069 B.C.)

The Egyptians avoided using the name of the reigning monarch, in the same way as we feel a certain awe at needlessly pronouncing the name of God. They therefore spoke of the king as: “Horus the lord of the palace, the good god, his Majesty, thy Lord," or (usually under the New Kingdom) instead of all these designations, they used the indefinite pronoun one to signify sacred power — “One has commanded thee," “One is now residing at Thebes," would be, in the older style, “The king has commanded thee," or “The king resides at Thebes. "

The Pharaoh was regarded as an incarnation of divinity, to whom shrines were erected, priests ordained, and sacrifices offered. In early times he was, moreover, declared to be the son of the goddess of the city in which he dwelt; it was not until the rise of the fifth historical dynasty that he became the “Son of the Sun-god” of Heliopolis, rather than Horus, the Sun-god, himself. This curious parallelism is one of many facts which point to intercourse between ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt in the prehistoric age; whether the deification of the King originated first on the banks of the Euphrates or of the Nile must be left to the future to decide. The Mesopotamia god Sin was addressed as “the god of Agadê,” or Akkad, the capital of his dynasty, and long lists have been found of the offerings that were made, month by month, to the deified Dungi, King of Ur, and his vassal, Gudea of Lagas. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Ra and the Pharaoh

Ra (Re) was the ancient Egyptian sun god. According to ancient Egyptian creation myth, before the world emerged from the waters of chaos Ra appeared. He was so powerful that all he had to do was say the name of something and it came into being. "I am Khepera at the dawn, and Ra at noon and Tum in the evening," he declared and the first day was created. When he cried "Nut" the goddess of the sky took her place between the horizons. And when he the shouted "Hapi" the sacred river Nile began flowing through Egypt. After filling the world with beautiful things Ra said the words "man" and "women" and thus people were created. Ra then transformed himself into man, thus becoming the first pharaoh. [Source: Roger Lancelyn Green, Tales of Ancient Egypt]

Ra was originally a local god. His cult began to grow from roughly the Second Dynasty, establishing him as a sun-deity. By the Fourth Dynasty, pharaohs were seen as Ra's manifestations on Earth, referred to as "Sons of Ra". Ra was called the first king of Egypt, thus it was believed pharaohs were his descendants and successors. His worship increased massively in the Fifth Dynasty, when Ra became a state-deity and pharaohs had specially aligned pyramids, obelisks, and sun temples built in his honor. The rulers of the Fifth Dynasty told their followers that they were sons of Ra himself and the wife of the high priest of Heliopolis. These pharaohs spent much of Egypt's money on sun-temples. The first Pyramid Texts began to arise, giving Ra more and more significance in the journey of the pharaoh through the Duat (underworld). [Source Wikipedia]

Atum-Ra (or Ra-Atum) was composite deity formed from two completely separate deities. Atum was more closely linked with the Sun, and was also a creator god of the Ennead. Both Ra and Atum were regarded as the father of the deities and pharaohs and were widely worshipped. In older myths, Atum was the creator of Tefnut and Shu, and he was born from the ocean Nun.

The ancient Egyptians believed the sun was a god (Ra) who visited the underworld, a watery realm of the demons of the dead, where he battled with the serpent of chaos, and victoriously returned to the day each morning. They believed the Sun-god Ra rode across the sky from east to west in a “day boat” and changed to a “night boat” for the return trip through the underworld. He rose in the jaws of a lion in the East and set in the jaws of a lion in the West and was guided at night through the waters of chaos. The myths about Ra, it has been argued, made sense to the ancient Egyptians because they did not contradict what they saw with the naked eye.

See Separate Articles: Old Kingdom Solar Temples Under ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TEMPLES: HISTORY, TYPES, LAYOUT africame.factsanddetails.com;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CREATION GODS AND MYTHS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CREATION OF MANKIND AND THE MYTH OF THE HEAVENLY COW africame.factsanddetails.com

Royal Procession of a Pharaoh

It was the custom of the court that the Pharaoh, or rather, according to the poetical language of Egypt, that the sun-god should shine when he rose from the horizon, and showed himself to the people; therefore whenever we see the Pharaoh outside his palace, he is surrounded by the greatest splendour. When according to ancient usage he is carried out in a sedan-chair, he is seated within it in full dress, two lions striding support the chair, the poles of which rest on the shoulders of eight distinguished courtiers. The fan-bearers accompany the king, fanning him with fresh air and waving bouquets of flowers near his head, that the air round the good god may be filled with sweet perfumes. The ordinary fan-bearers walk in front and behind the monarch, but the high official, who accompanies the king "as his fan-bearer on the right" carries a beautiful fan and a small bouquet as the insignia of his rank, and leaves the work to the servants. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

A representation at Tell el Amarna of King Akhenaten visiting his god the Sun-disk, shows us how the royal family set out: The procession moves out of the courts of the royal palace surrounded by the greatest pomp and splendour. Two runners with staves hasten first to clear the way through the inquisitive crowd for the king's chariot. Following close behind them comes His Majesty drawn by fiery richly-caparisoned horses, with which the servants can scarcely keep pace. On either side is the bodyguard on foot, running; Egyptian soldiers and Asiatic mercenaries armed with all kinds of weapons; their badges are borne before them, and behind them the officers follow driving. After the king's chariot come those of his consort and of his daughters, two of the young princesses drive together, the elder holds the reins, while the younger leans tenderly on her sister. Behind them come six carriages with the court ladies, and on either side six more with the lords of the bed-chamber. Runners and servants hasten along on both sides swinging their staves.

A more splendid spectacle can scarcely be imagined than this procession as it passed quickly by the spectators; the gilded chariot, the many-colored plumes of the horses, the splendid harness, the colored fans, the white flowing garments, all lighted up by the glowing sun of Egypt.

Pharaoh's Funeral

Pharaohs were obsessed with afterlife. When a pharaoh died he became the god Osiris. When the Pharaoh died and was buried, or rather as the Egyptians would have said, “when he like the sun-god has set below the horizon, and all the customs of Osiris have been fulfilled for him; when he has passed over the river in the royal bark and gone to rest in his eternal home to the west of Thebes," then the solemn accession of his son takes place. “His father Amun, the lord of the gods, Ra, Atum, and Ptah beautiful of face, the lords of the two countries, crown him in the place of his forefathers; joyfully he succeeds to the dignity of his father; the country rejoices and is at peace and rest; the people are glad because they acknowledge him ruler of the two countries, like Horus, who governs the two countries in the room of Osiris. He is crowned with the Atef crown with the uraeus; to which is added the crown with the double feathers of the god Tatenen; he sits on the throne of Hannachis, and is adorned like the god Atum. " [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The day before a Pharaoh’s funeral the king's mummy was placed in the royal palace to lie in state. On the day of the funeral itself the Pharaoh's widow stood at the mummy's feet reciting formulas of rebirth. Then a procession carried the coffin to a temple for four days of rituals. After this the deceased pharaoh was taken to his tomb. His successor touched his mouth and eyes to open them for eternal life; burial furniture was brought in, and the king's coffin was set upright; and finally the tomb was sealed. Usually the first thing the new pharaoh did when he claimed the throne was erase the name of his predecessor on all the monuments in the empire and replace them with his own.♀

Funerals usually began in the morning with people gathering at the house of the deceased. The gathering included family members, friends, priests, attendants, singers and professional mourners. During the procession a “tekenu” (a stand in for the deceased that served as a scapegoat for evil deeds) was dragged by oxen on a sled. It was followed by a “reserve body” statue of the deceased — usually accompanied by priests and attendants — that was buried with the deceased. Food and objects were carried for a feast and to be buried with the dead.

The first part of the funeral for a Pharaoh or other important person was a procession down to Nile, where they were everyone was loaded into two boats to the cemetery. Professional mourners accompanied by procession and wailed loudly, rubbed dirt and garbage on themselves and pulled their hair and clothes.

The centerpiece of the procession on land was still the boat that carried the coffin. It was mounted on a sled, engraved and covered with embroidery. Near the coffin were two kneeling, living women playing the roles of Isis and Nephthys, two goddesses that helped protect and guide the dead during their afterlife journey. Harold Hays of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “In all periods, the focal point of the procession to the tomb was an overland transport of the deceased on a sledge drawn by cattle and accompanied by citizenry of high and low station and friends. Priests burn incense and libate milk before the sledge, which is attended by the two mourners, and grave goods are carried to the tomb.

See Separate Article: FUNERAL FOR AN EGYPTIAN PHAROAH africame.factsanddetails.com ANCIENT EGYPTIAN FUNERALS: RITUALS, PROCESSION AND MOURNING africame.factsanddetails.com

Valley of the Kings and Queens

Valley of the Kings is the burial ground of the pharaohs of the New Kingdom, which ruled around 1500 B.C. to 1100 B.C. Known to the ancient Egyptians as “The Great and Majestic Necropolis,” the valley is surrounded by barren mountains, with largest being Al-Qurn (the Horn). According to the Theban Mapping Project the earliest confirmed royal tomb in the valley was built by Thutmose I (reign 1504 to 1492 B.C.). His predecessor Amenhotep I (reign 1525 to 1504 B.C.) may also have had his tomb built in the Valley of the Kings, although this is a matter of debate among Egyptologists.

Made at a time when Egypt was at a peak in its wealth and influence, the tombs in the Valley of the Kings are carved deep into the rock faces of the valley walls and composed of several rooms and corridors leading down to the burials chambers. Artists and masons carved and decorated kilometers of underground corridors: not only for kings but also their wives, children and principal ministers. The tombs were once filled with unimaginable wealth, hinted at by the artifacts found in the tomb of King Tutankhamun (King Tut), who was a relatively minor king with a relatively modest tomb. The other tombs were all looted of their treasures millennia ago.

The Valley of the Queens is where most of the wives and children of the important New Kingdom pharaohs were buried. The tombs are similar to the tombs in the Valley of Kings in that they are carved into the rock faces of the valley walls of limestone cliffs and arid, eroded mountains, and are composed of several rooms and corridors leading to the burials chambers. Only five of the more than 70 tombs are open to visitors. The Valley of the Queens is closer to the ticket office than the Valley of the Kings. It is still a considerable distance from Luxor.

See Separate Article: VALLEY OF THE KINGS africame.factsanddetails.com

Herodotus on Pharaohs and Gods

Opening of the Mouth of Tutankhamun (King Tut)

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “Hecataeus59 the historian was once at Thebes , where he made a genealogy for himself that had him descended from a god in the sixteenth generation. But the priests of Zeus did with him as they also did with me (who had not traced my own lineage). They brought me into the great inner court of the temple and showed me wooden figures there which they counted to the total they had already given, for every high priest sets up a statue of himself there during his lifetime; pointing to these and counting, the priests showed me that each succeeded his father; they went through the whole line of figures, back to the earliest from that of the man who had most recently died. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“Thus, when Hecataeus had traced his descent and claimed that his sixteenth forefather was a god, the priests too traced a line of descent according to the method of their counting; for they would not be persuaded by him that a man could be descended from a god; they traced descent through the whole line of three hundred and forty-five figures, not connecting it with any ancestral god or hero, but declaring each figure to be a “Piromis” the son of a “Piromis”; in Greek, one who is in all respects a good man.

“Thus they showed that all those whose statues stood there had been good men, but quite unlike gods. Before these men, they said, the rulers of Egypt were gods, but none had been contemporary with the human priests. Of these gods one or another had in succession been supreme; the last of them to rule the country was Osiris' son Horus, whom the Greeks call Apollo; he deposed Typhon,60 and was the last divine king of Egypt. Osiris is, in the Greek language, Dionysus. So far I have recorded what the Egyptians themselves say. I shall now relate what is recorded alike by Egyptians and foreigners, and shall add something of what I myself have seen.”

Horus Versus Seth and Pharaonic Rule

On the fight between Horus and Seth at the beginning of creation, Lee Huddleston of the University of North Texas wrote in Ancient Near East Page: “Father Geb faced a unique problem. Atum had resigned his rule to his only son, Shu; Shu in turn gave way for his only son, Geb. Geb had two sets of twins from Nut's one pregnancy. When it came time for him to turn over control of earth [EGYPT], he had two sons from which to choose the next ruler. Some stories suggest he may have divided Egypt; others say he gave it all to Osiris and gave the rest of the world to Seth. Whatever the circumstance may have been, Seth was unhappy with his lot. He murdered his brother, Osiris; cut his body into small pieces, and threw them into the NILE. There, Osiris merged with, and became the River. Isis, assisted by her sister, Nepthys, found all the pieces of Osiris except the phallus. Isis hovered over him imploring him to arise and impreg-nate her. Miraculously, Osiris did revive, and did impregnate his wife before passing to the West, the home of Atum, where he became the Spirit in whom the souls of the righteous dead would eventually find salvation. [Source: Lee Huddleston, Ancient Near East Page, January, 2001, Internet Archive, from UNT \=/]

“In term, Isis gave birth to Horus. She hid him from his uncle, Seth, until he was eighteen. Then she presented Horus to the Council of the Gods arguing that, as the only son of Osiris, Horus ought to be given his father's realm [Egypt]. Geb was unable to decide whether the young Horus or the older and stronger Seth should rule. There followed a series of contendings between the ex-ruler's brother and his son to determine which of them was best suited to rule Egypt. In the process, Seth was tricked into admitting that a son's rights of inheritance took precedence over the rights of a brother; and into the appearance of having dishonored himself. As a result of these contendings, the following conventions evolve.

“1) Horus is always P haraoh, and Pharaoh was King of Egypt by Right of Divinity. (In actuality, not all Pharaohs claimed to be Horus; some identified with Seth, especially if they were involved with foreign lands or their capitals lay in Seth's land; others identified with their own preferred gods.) The idea of a Divine King persisted in the Mediterranean basin until the triumph of monotheistic religions more than 3400 years later. 2) Pharaoh, at first possessed sole right to enter Heaven, but by 2200 B.C. the spiritual dynamics of Salvation were understood and the Democratization of Heaven completed.

“3) The Rule of primogeniture was another victor in the struggle between Horus and Seth for the birthright of Osiris. Horus, Isis, and their supporters used the argument that Osiris, the first born son of Geb, rightfully owned Egypt and that his Domain should pass intact to his Son, not to his brother. Horus' victory was, retroactively, a victory for Osiris' contention in his earlier quarrel with Seth. The Institution called Primogeniture has endured for more than five thousand years, but has declined in social acceptance with the decay of the Institution called the Nobility.”

See Separate Article: HORUS, THE FALCON-HEADED PATRON OF KINGS africame.factsanddetails.com

Herodotus Tale of Rhampsinitus (the Fictitious Egyptian King)

In his story of Rhampsinitus, a fictitious Egyptian king, Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “The next to reign after Proteus (they said) was Rhampsinitus. The memorial of his name left by him was the western forecourt of the temple of Hephaestus; he set two statues here forty-one feet high; the northernmost of these the Egyptians call Summer, and the southernmost Winter; the one that they call Summer they worship and treat well, but do the opposite to the statue called Winter. 121A. This king (they told me) had great wealth in silver, so great that none of the succeeding kings could surpass or come near it. To store his treasure safely, he had a stone chamber built, one of its walls abutting on the outer side of his palace. But the builder of it shrewdly provided that one stone be so placed as to be easily removed by two men or even by one. So when the chamber was finished, the king stored his treasure in it, and as time went on, the builder, drawing near the end of his life, summoned his sons (he had two) and told them how he had provided for them, that they have an ample livelihood, by the art with which he had built the king's treasure-house; explaining clearly to them how to remove the stone, he gave the coordinates of it, and told them that if they kept these in mind, they would be the custodians of the king's riches. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“So when he was dead, his sons got to work at once: coming to the palace by night, they readily found and managed the stone in the building, and took away much of the treasure. 121B. When the king opened the building, he was amazed to see the containers lacking their treasure; yet he did not know whom to accuse, seeing that the seals were unbroken and the building shut fast. But when less treasure appeared the second and third times he opened the building (for the thieves did not stop plundering), he had traps made and placed around the containers in which his riches were stored. The thieves came just as before, and one of them crept in; when he came near the container, right away he was caught in the trap. When he saw the trouble he was in, he called to his brother right away and explained to him the problem, and told him to come in quickly and cut off his head, lest he be seen and recognized and destroy him, too. He seemed to have spoken rightly to the other, who did as he was persuaded and then, replacing the stone, went home, carrying his brother's head. 121C. When day came, the king went to the building, and was amazed to see in the trap the thief's body without a head, yet the building intact, with no way in or out. At a loss, he did as follows: he suspended the thief's body from the wall and set guards over it, instructing them to seize and bring to him any whom they saw weeping or making lamentation.

“But the thief's mother, when the body had been hung up, was terribly stricken: she had words with her surviving son, and told him that he was somehow to think of some way to cut loose and bring her his brother's body, and if he did not obey, she threatened to go to the king and denounce him as having the treasure. 121D. So when his mother bitterly reproached the surviving son and for all that he said he could not dissuade her, he devised a plan: he harnessed asses and put skins full of wine on the asses, then set out driving them; and when he was near those who were guarding the hanging body, he pulled at the feet of two or three of the skins and loosed their fastenings; and as the wine ran out, he beat his head and cried aloud like one who did not know to which ass he should turn first, while the guards, when they saw the wine flowing freely, ran out into the road with cups and caught what was pouring out, thinking themselves in luck; feigning anger, the man cursed all; but as the guards addressed him peaceably, he pretended to be soothed and to relent in his anger, and finally drove his asses out of the road and put his harness in order. And after more words passed and one joked with him and got him to laugh, he gave them one of the skins: and they lay down there just as they were, disposed to drink, and included him and told him to stay and drink with them; and he consented and stayed. When they cheerily saluted him in their drinking, he gave them yet another of the skins; and the guards grew very drunk with the abundance of liquor, and lay down right there where they were drinking, overpowered by sleep; but he, when it was late at night, cut down the body of his brother and shaved the right cheek of each of the guards for the indignity, and loading the body on his asses, drove home, fulfilling his mother's commands. 121E.

“When the king learned that the body of the thief had been taken, he was beside himself and, obsessed with finding who it was who had managed this, did as follows—they say, but I do not believe it. He put his own daughter in a brothel, instructing her to accept all alike and, before having intercourse, to make each tell her the shrewdest and most impious thing he had done in his life; whoever told her the story of the thief, she was to seize and not let get out. The girl did as her father told her, and the thief, learning why she was doing this, did as follows, wanting to get the better of the king by craft. He cut the arm off a fresh corpse at the shoulder, and went to the king's daughter, carrying it under his cloak, and when asked the same question as the rest, he said that his most impious act had been when he had cut the head off his brother who was caught in a trap in the king's treasury; and his shrewdest, that after making the guards drunk he had cut down his brother's hanging body. When she heard this, the princess grabbed for him; but in the darkness the thief let her have the arm of the corpse; and clutching it, she held on, believing that she had the arm of the other; but the thief, after giving it to her, was gone in a flash out the door. 121F.

“When this also came to the king's ears, he was astonished at the man's ingenuity and daring, and in the end, he sent a proclamation to every town, promising the thief immunity and a great reward if he would come into the king's presence. The thief trusted the king and came before him;Rhampsinitus was very admiring and gave him his daughter to marry on the grounds that he was the cleverest of men; for as the Egyptians (he said) surpassed all others in craft, so he surpassed the Egyptians.” 122.

Herodotus on Rhampsinitus and the Demeter Story

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “They said that later this king went down alive to what the Greeks call Hades and there played dice with Demeter, and after winning some and losing some, came back with a gift from her of a golden hand towel. From the descent of Rhampsinitus, when he came back, they said that the Egyptians celebrate a festival, which I know that they celebrate to this day, but whether this is why they celebrate, I cannot say. On the day of the festival, the priests weave a cloth and bind it as a headband on the eyes of one of their number, whom they then lead, wearing the cloth, into a road that goes to the temple of Demeter; they themselves go back, but this priest with his eyes bandaged is guided (they say) by two wolves49 to Demeter's temple, a distance of three miles from the city, and led back again from the temple by the wolves to the same place. 123. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“These Egyptian stories are for the benefit of whoever believes such tales: my rule in this history is that I record what is said by all as I have heard it. The Egyptians say that Demeter and Dionysus are the rulers of the lower world.50 The Egyptians were the first who maintained the following doctrine, too, that the human soul is immortal, and at the death of the body enters into some other living thing then coming to birth; and after passing through all creatures of land, sea, and air, it enters once more into a human body at birth, a cycle which it completes in three thousand years. There are Greeks who have used this doctrine, some earlier and some later, as if it were their own; I know their names, but do not record them. 124.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Amarna Palace, the Amarna Project

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024