Home | Category: Death and Mummies

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN FUNERALS AND WILLS

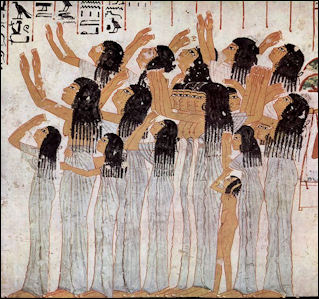

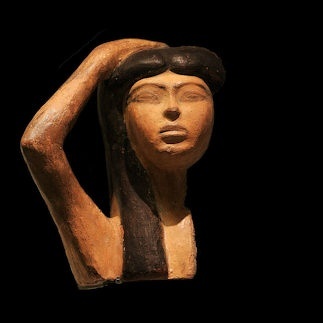

Wailing women at a funeral Funerals for commoners are believed to have been relatively simple affairs in which friends and family gathered and the deceased was buried while prayers were read. Funerals for royals, aristocrats and high officials and priests were more public and elaborate affairs that included a funeral procession, magic rites and climaxed with a funerary feast and the sealing of the tomb.

Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote for the BBC:“For ancient Egyptians, it was of key importance that when someone died their physical body should continue to exist on earth, so they could progress properly through the afterlife. Consequently, providing proper eternal accommodation for their body after they had died was very important to them. The afterlife they wanted to attain was thought of as a bigger and better version of the earthly Egypt-and in it they were to live close to their family and friends. [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, BBC, February 17, 2011]

“There was one exception to this rather homely vision of the next world. This was for the king, already a divine being on earth, who would complete his apotheosis on death. According to the earliest set of texts dealing with the next world, the Pyramid Texts, which were inscribed inside the royal tombs of 2500-2300 B.C., the king would dwell with his fellow gods in the entourage of the sun-god, Re. He would spend eternity traversing the sky and underworld: one might be tempted to regard the fate of his subjects as more desirable.” |::|

According to the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago: “The funerary customs and beliefs of the ancient Egyptians called for the preservation of the body and ample provisions for the after-life. This was envisaged as a continuation of the existence before death. An ancient Egyptian would provide for the life in the Next World as best as his economic abilities would allow. For us today, this means that a huge amount of information about daily life in ancient Egypt can be found in the tombs. Detailed and colourful scenes on the walls provide information on a wide range of topics including dress, agriculture, architecture, as well as crafts and food production, and the goods included in the tomb along with the corpse add to this information resource....The tomb owner would also need his body to be as well preserved as possible, as it was a constituent part of the deceased's being and the dwelling place of the ba... Examination of mummies provides information on health, diet and life-expectancy.[Source: ABZU, University of Chicago Oriental Institute, oi-archive.uchicago.edu ]

In the world's oldest known will, Nek'ure, the son of an Egyptian Pharaoh who died in 2601 B.C., provided for the disposition of 14 towns and estates, which were distributed among his wife, three children and an unknown woman. Hieroglyphic on the wall of his tomb read the young Egyptian royal would make decisions "while living upon his two feet and not ailing in any respect."

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Death and Burial in Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2015) Amazon.com

”Burial Customs in Ancient Egypt: Life in Death for Rich and Poor”, Illustrated,

by Wolfram Grajetzki (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Egyptian Book of the Dead (Penguin Classics) by Wallace Budge and John Romer (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day” The Complete Papyrus of Ani Featuring Integrated Text and Full-Color Images, Illustrated, by Dr. Raymond Faulkner (Translator), Ogden Goelet (Translator), Carol Andrews (Preface) (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the Egyptian Book of the Dead” by Rita Lucarelli and Martin Andreas Stadler (2023) Amazon.com;

“Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection, (Volume 1), Illustrated, by Sir Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge (1857-1934) Amazon.com;

“Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt” by Jan Assmann (2005) Amazon.com;

“Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt” by John H Taylor (2001) Amazon.com;

“Living with the Dead: Ancestor Worship and Mortuary Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Nicola Harrington (2012) Amazon.com;

“Recycling for Death: Coffin Reuse in Ancient Egypt and the Theban Royal Caches” by Kara Cooney (2024) Amazon.com;

Funerary Rituals in Ancient Egypt

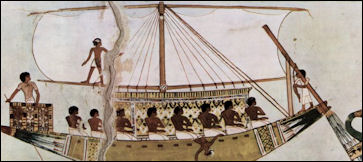

funerary boat Harold Hays of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “Upon death, the Egyptian was the object of a series of ceremonies performed by priestly officiants. The stages of the procedure largely correspond to the practical steps taken following death. These were: taking the corpse to a place of embalming, the embalming itself, taking the corpse to the tomb, and interment. The words and actions of the rituals superimposed upon these practical matters had a clear metaphysical purpose: funerary rituals were intended to elevate the mortal to the superhuman. Where best preserved and represented, the rituals make him out to be a god, specifically Osiris, and also to be an akh (an exalted spirit), and one “true of voice” (mAa xrw)....Though details vary between different chronological periods, seven major complexes of funerary rituals may be discerned (see below). The following discussion gives a general account of the sorts of rituals performed for the dead, from death through interment and afterwards. It takes scenes from the first part of the 18th Dynasty as a point of reference, in particular those from the tomb of Rekhmire.”

[Source: Harold Hays, Universiteit Leiden, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“As to the social differentiation of funerary rituals, it is commonplace in Egyptological literature to mention a “democratization of the afterlife.” This is a historical model which supposes that in the earliest times, the Egyptians believed that a beatified afterlife was accessible exclusively to royalty, and only in later periods to non-royal persons. But the premise of this model rests merely in an absence of Pyramid Texts in the tombs of elites in the Old Kingdom. Recent research has put forth evidence showing the model to be deeply flawed. Since the Old Kingdom, the elite aspired to ascend to the great god after death and had the knowledge to get himself there; moreover, throughout the Pharaonic period and beyond, both elite and king used the same stereotyped scenes in

Since death was one of the most powerful generators of Egyptian culture, there is a wide variety of evidence related to Egyptian funerary rituals: textual, pictorial material, and architectonic. “Painted and inscribed pictorial scenes of rites from funerary rituals appear in all periods of Pharaonic Egypt, from the Old through New Kingdoms. They occur principally in the cultic areas of tombs prepared for non-royal elite males, and such scenes usually cluster around cultic foci, above all, the false door. They do appear elsewhere, notably in certain vignettes in Books of the Dead beginning in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.). Also, there are scenes showing women as the principal object of precisely the same rites as for men. As one might expect, the data from a timespan of about a millennium and a half is not homogeneous: the activities represented differ in smaller and greater degrees over time, with such differences presumably reflecting changes in practice. Also, since transport was involved, local topography must necessarily have had influence. Running counter to the impulse to show contemporaneous and local practice were impulses of tradition and idealization. Many texts giving information about funerary rituals are directly associated with the pictorial scenes. In the New Kingdom Theban tomb of Rekhmire and elsewhere, the longer hieroglyphic recitations embedded within the scenes and abutting them are often verbatim parallels of texts that were already ancient.

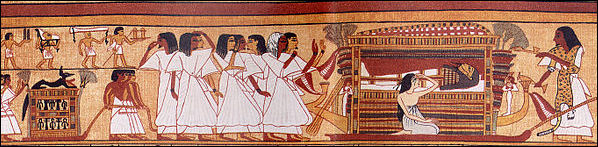

Funeral Procession on the Nile for a Pharaoh

Funerals usually began in the morning with people gathering at the house of the deceased. The gathering included family members, friends, priests, attendants, singers and professional mourners. During the procession a “tekenu” (a stand in for the deceased that served as a scapegoat for evil deeds) was dragged by oxen on a sled. It was followed by a “reserve body” statue of the deceased — usually accompanied by priests and attendants — that was buried with the deceased. Food and objects were carried for a feast and to be buried with the dead.

Offering bearers The first part of the funeral for a Pharaoh or other important person was a procession down to Nile, where they were everyone was loaded into two boats to the cemetery. Professional mourners accompanied by procession and wailed loudly, rubbed dirt and garbage on themselves and pulled their hair and clothes.

Squatting near the body are the women relations of the deceased with their breasts bare, lamenting him; the funerary priest makes offerings and burns incense before the mummy. His official recitation, “an incense offering to thee, O Harmachis-Khepri, who art in the bark of Nun, the father of the gods, in that Neshmet bark, which conducts thither the god and Isis and Nephthys and this Horus, the son of Osiris," contrasts strangely with the lamentations of the women who, while they grieve that their husband and father has forsaken them, have no understanding of the subtle mysticism of these ceremonies. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The boat in front of the funerary bark also contains women, who sit on the deck and make their lamentations towards the mummy; a near relation of the deceased stands in the bows of this boat and calls out to the helmsman: “Steer to the west, to the land of the justified. The women of the boat weep much, very much. In peace, in peace to the west, thou praised one, come in peace. . . . When time has become eternity then shall we see thee again, for behold, thou goest away) to that country in which all are equal."

In a third boat are the male relations, whilst the fourth is occupied by the colleagues and friends of the deceased, who carry the insignia of their office, and are come to render the last honurs to him who is gone, and to lay in his tomb their presents, which arc borne before them by their servants. The words of these prophets, princes and priests are of course less impassioned; they admire the crowd of followers: “Oh how beautiful is that which befalls him. . . . because of the great love he bore to Khons of Thebes he is allowed to attain to the West followed by tribe after tribe of his servants." When these boats and the little barks containing the servants with bouquets of flowers, offerings of food, and boxes of all kinds, have all arrived at the western shore, the real funeral procession begins. '

Funeral Procession on the Land for a Pharaoh

The centerpiece of the procession on land was still the boat that carried the coffin. It was mounted on a sled, engraved and covered with embroidery. Near the coffin were two kneeling, living women playing the roles of Isis and Nephthys, two goddesses that helped protect and guide the dead during their afterlife journey. Harold Hays of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “In all periods, the focal point of the procession to the tomb was an overland transport of the deceased on a sledge drawn by cattle and accompanied by citizenry of high and low station and friends. Priests burn incense and libate milk before the sledge, which is attended by the two mourners, and grave goods are carried to the tomb. According to the caption of a depiction of the event, its goal is “to proceed in peace up to the horizon, to the Field of Rushes, to the netherworld, in order to lead him to the place where the great god is”: even as he is transported in this world to the tomb, the deceased is also transported to the world beyond, where he will be reborn with the sun. The procession culminates at a tomb represented as the personified western desert (zmjt jmntjt). This goddess is said to call out to the dead “that I embrace you with my arms, that I lead life to you, that I indeed be the protection of your body”. [Source: Harold Hays, Universiteit Leiden, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Martin Stadler of Wuerzburg University wrote: A funeral procession can be considered a “rite of passage” through which the deceased was prepared for his or her transition into the hereafter and which actually constituted the first steps of that transition. The funeral procession is depicted in the vignette of the Book of the Dead, spell 1, a depiction that evolved from a representation of a mere coffin in the early 18th Dynasty to more elaborate scenes showing the tomb as the destination of the procession, the rites performed for the deceased by the sem-priest and the lector priest, the wailing women mourners, and the deceased’s tomb equipment being carried along. The vignette also appears in private tombs of the elite. A comparison of scenes in the tomb of 18th- Dynasty king Tutankhamen with those in private (i.e., non-royal) tombs has revealed that royal burial customs were pictorially represented—that is, copied—in private tombs; we therefore do not have depictions of private funerals. This conclusion may be further supported by the fact that, in private tombs, crowns and regalia are among the grave goods depicted—items that certainly would not have been included in non-royal burials. Thus representations of funeral processions were idealized, showing us more of the state to which the deceased aspired than of his or her reality. [Source: Martin Stadler, Wuerzburg University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

Funeral procession

Processions to the Necropolis and Embalming Place

Harold Hays of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “Upon death, the corpse was transported from the dwelling to the necropolis. The most important leg of the ceremonial transport was waterborne, corresponding to a transfer across the Nile from the east, the land of the living, to the west, the land of the dead. Usually the crafts are depicted as papyrus rafts, a traditional form, with the deceased riding shielded from view within a sarcophagus, or a vertical chest is shown, representing an enclosure for the deceased’s statue. The weight of significance is placed upon the arrival at the west bank, where the gods of the netherworld are informed that the deceased has arrived xpr m nTr, “transformed into a god”. [Source: Harold Hays, Universiteit Leiden, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

The especially detailed scenes in the tomb of Rekhmire give the craft the same form as the Neshmet boat of the god Osiris, the boat which bears that god at his mysteries celebrated at the city Abydos. Actual crafts of this form, which is the same as that depicted for the sun-god Ra as he passes through the netherworld, were sometimes buried within mortuary complexes. Along with the landing, extensive royal offerings (hetep di nesut) are consecrated to the ka of the deceased, consisting of offerings from important gods. The sacerdotal recitations accompanying the actions already name the deceased as the god Osiris.

“Priestly roles were gender specific in this and all of the rituals to follow. Two of the most important were a pair of women identified as mourners (Drtj), filling the roles of the goddesses Isis and Nephthys as they attend their dead brother, Osiris. Notably, one of these mourners participates in the sacrifice of a bull at the mooring, with such sacrifices occurring at effectively each following stage of the funeral. The god embodied in the bull was undoubtedly Seth , slayer of Osiris. Among other officiants in these and subsequent rites were priests representing the gods Horus and Thoth, called the sem-priest and lector priest respectively.

“Having arrived at the necropolis and taken command of the denizens of the necropolis, “the ones whose places are hidden”, the deceased was borne toward the “god’s booth” (zH-nTr), a structure intimately associated with Anubis, god of embalming. A censing priest leads overland, followed by the two mourners and nine pallbearers called “friends” (smrw). The friends are said to be the (four) Children of Horus, while the number nine is an allusion to the full plurality of the divine pantheon. Here, the friends carry the corpse in a chest and say, “Let his son Horus give him (sc. his enemy, Seth) to him; let his Wereret-crown be presented to him before the gods”, with the crown being emblematic of success at the judgment of the dead. Grave goods contained in boxes are hoisted on shoulders and carried in free hands, and great armfuls of divine offerings from the estates of gods and royal mortuary temples are marched to the god’s booth. In the scenes in the tomb of Rekhmire, the arrival is called “a landing to be purified (lit. released) at the stair of libation.” The arrival is announced by numerous recitations from a chorus of friends and other officiants.”

funeral procession

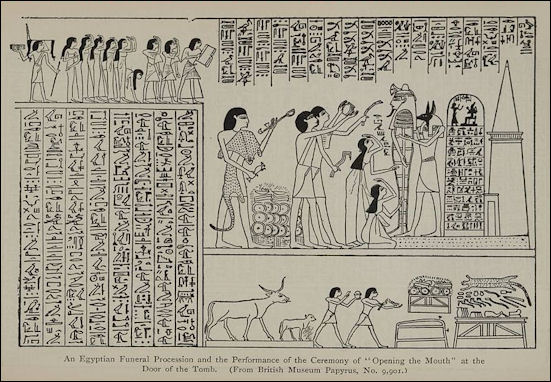

Opening the Mouth Ceremony

The most important ceremony at the funeral was the “opening of the mouth ceremony,” performed by a priest who played the role of Horus. After the deceased was taken from the boat important spells and prayers were chanted, while the priest touched the deceased’s face and face of the reserve body with a sacred flint stone. This symbolically opened the eyes and mouth of the deceased for the afterlife.

With mouth of the deceased open and able to eat, the feast could commence. The tekenu was ritually “killed” and the oxen that dragged it were sacrificed. The right foreleg, symbolizing virility, of one of the slaughtered animals was presented to the deceased. During the final goodbye to the dead, prayers were chanted that ensured safe the passage for the dead to the afterlife. Incense were burned. Libations were poured. And the body was placed in the tomb. If the deceased was poor he was placed in a hole. If he was rich he was placed in a sarcophagus within the tomb along with numerous objects for the journey. Some grave objects were “killed,” broken, so they could be used immediately by the deceased. Finals prayers were said as the tomb was filled with rocks and resealed with mortar by a mason. While the mason was doing his job, people sat down by the tomb and feasted in honor of the dead.

Harold Hays of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “With the mummy now arrived at the tomb, it was placed outside with its face to the south,and the Opening of the Mouth ritual was performed. Although this ritual is named in sources since the beginning of the 4th Dynasty, full pictorial and textual representations do not occur until the 18th Dynasty, when it is seen to consist of a few lengthy sections. First, the mummy was treated as if it were a statue of the deceased undergoing fabrication. Its design and creation was enacted, and twice a sacrifice was performed and the statue’s mouth symbolically opened by means of presenting adze-shaped instruments to the face. The purpose of the mouth opening is explicitly to permit the deceased to speak to the Great Ennead in the House of the Noble which is in Heliopolis, that he take the Wereret-crown thereby”: it gives him the ability to verbally defend himself at the judgment of the dead and attain vindication. Second, a preliminary offering ritual is performed, the numerous rites of which are called “glorifications,” or, literally, “that which makes one into an akh” (sAxw). The mummy is then put into the burial chamber, with this act described as “making the god enter his temple”. Following the interment, the last portion of the Opening of the Mouth involves further offerings to the gods and a declaration of the ritual’s completion. [Source: Harold Hays, Universiteit Leiden, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“By virtue of the physical transport involved, the rituals prior to the Opening of the Mouth imply transitional periods between former states of being (in the human experience: living, dying, corpse) and desired ones (god, akh, justified dead) even though, by virtue of the symbology of their recitations, the earlier rituals express these desired states as having already been accomplished. Since, in contrast, the Opening of the Mouth centers upon the exposed and motionless deceased, the achievement of the desired states is stressed.”

Opening the Mouth

Mortuary Service of an Ancient Egyptian Funeral

Harold Hays of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “After interment, sacerdotal service was regularly performed at the above-ground cult place. Stereotyped scenes, showing rites performed before the deceased while he is seated at an offering table, appear in royal and elite tombs since the Old Kingdom and continue through the New Kingdom. Usually, these scenes are displayed at the very focus of the cult place, and usually a tabular offering list is embedded within them. These offering lists represent a series of rites ideally performed every day at that spot by priests. [Source: Harold Hays, Universiteit Leiden, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Chief of these was the sem-priest, who was, in theory, the son of the deceased, and therefore the god Horus to the god Osiris. Since the god Horus was involved, this priest was archetypically the king himself. In practice, the royal role was filled by delegates – familial or otherwise – to whom income could be bequeathed in recompense for this service. The rites of the oldest and most classical offering list are given in full in the Pyramid Texts. They integrate speech, actions, and objects, and, as with the Opening of the Mouth’s offering ritual, the rites are designated “glorifications” (sAxw). These “glorifications” consist mainly of the presentation of food items, but other activities such as censing and the application of oils are involved as well.

“Beginning in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.), scenes of daily mortuary service are sometimes displayed together with passages of Pyramid Texts involving purely oral rites. Daily performances at the tomb cult place, and at statues of the deceased emplaced in temples, were supplemented by calendrical events such as the Sokar Festival throughout Egypt and the Valley Festival at Thebes. Some of these calendrical events may have sometimes involved temporary access to the sealed, subterranean burial places. Occasional rites, such as the presentation and recitation of Letters to the Dead, would also have taken place in the vicinity of the tomb.”

Ritual Objects Used During an Ancient Egyptian Funeral

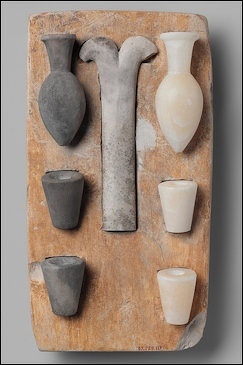

model of Opening the Mouth tools

Dorothea Arnold of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The process of mummification and the deposition of a mummy into the tomb were accompanied by elaborate rituals. Some objects from KV 54 were presumably used during these rites. [Source: Dorothea Arnold, Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2010, metmuseum.org\^/]

“1) Purification and Libation: a) Flasks with ovoid bodies and tall narrow necks were part of a hand-washing set during the Middle and New Kingdom: a person stretched his/her hands over a basin while a servant poured water over them from a flask. This mundane activity became a ritual when connected to an offering ceremony. B) Beakers and jars with wide necks were commonly used as containers of liquids and people also drank from them. Representations of purification rituals, however, also show them in use for pouring water over the heads of persons and mummies during purification rites. Between forty and fifty miniature basins were found in KV 54. They are shaped like the tubs in which priests washed before entering a temple or tomb for service. Their small size (around 5 1/2 to 6 inches [14–15.2 cm]) and friable material (unfired clay) made them purely symbolical objects. \^/

“Offerings: Since the dead were believed to need food and drink in the afterlife, offerings of liquids such as water, beer, or wine, and food such as bread, meat, fruits, and vegetables were an important part of all funeral rites in ancient Egypt. Among the objects from KV 54 were remains of meat offerings, plates, and dishes as well as a beautifully painted bowl that might well have served to present food, and some of the jars—if not used for purification—might have also contained liquid offerings or fragrant oils and ointments. \^/

“Floral Adornment: Among the most remarkable objects found in KV 54 are three astonishingly well preserved collars of plant leaves, berries, and flowers (09.184.214–.216). The color scheme was most prominently derived from alternating rows of olive leaves with the silvery undersides showing and olive leaves with the dark green upper sides showing, orange-red berries of Withania somnifera, blue cornflowers, and tiny blue faience beads, as well as yellow flowers of oxtongue (Picris asplenoides). The papyrus background was white and on two of the collars the edges along the neck was lined with red linen.” \^/

Ancient Egyptian Mourning Period and Burials

The death of a pharaoh was followed by a 70 day period of mourning in which normal life came to an abrupt halt. During that period no one was allowed to drink wine, eat meat, bath, conduct sacrifices or have sex. People were expected to weep openly in the streets to express their sorrow. Professional mourners covered their heads with mud and sang dirges. Husbands and wives sometimes mourned their deceased spouses by limiting their intake of food and water for several months and going celibate for several years.

Egyptian dead were always buried, never cremated. Up until Islamic times, the dead in Egypt were buried facing the rising sun in the East with the head pointing to the north. Cemeteries were always on the western side of the Nile because the sun set in the west. Often they were close enough to the river so that funeral processions coming down the Nile could easily reach the graves.

Ancient Egyptians who died around 3500 B.C. were often laid to rest lying on a mat on their left side in the fetal position, facing the west and the setting sun. In some cases the bodies were decapitated after death and placed back on the body in the tomb, which appears to indicate ritual dismemberment and reassemblage.

Most mummies wee anonymous. The likenesses on the coffins often looked nothing like the mummy inside but were idealized representations. Royal mummies were placed in a series of coffins, which went inside a sarcophagus which went into a series of shrines. The inner coffins and the tombs were inscribed with hieroglyphic texts of protective spells. Some coffins were made of basalt. Some sarcophagus were made of red granite. the lid of a large sarcophagus could weigh 2.7 tons and be covered with hieroglyphics on one side and the goddess Nut in a transparent gown on the other. There were also reusable coffins.

The outer coffin for King Tutankhamun was adorned with garlands of willow and olive leaves, wild celery, lotus pedals and cornflowers which suggests he was buried in the spring. See King Tutankhamun (King Tut).

Human sacrifices may have been practiced by the earliest pharaohs (See History). Real people were not sacrificed and buried with the dead as was the case sometimes with the Mesopotamians and other cultures. This practice may have been practiced in the early days, which possibly is how the custom of burying substitutes and shabti figures began.

Ancient Egyptian Funerary and Festival Rites That Live On in Coptic Christianity

Saphinaz-Amal Naguib of the University of Oslo wrote: “Coptic funerary rituals in today’s Egypt show many analogies to well-documented ancient Egyptian religious practices. Animal sacrifice, for example, is performed at the doorstep of the main entrance of the house when the coffin is taken out, on the same day at the cemetery, at the end of the mourning period, and periodically before the visits to the dead. The meat is distributed to the poor. However, due to various factors, these rituals have almost disappeared from large towns and cities. Visits to the dead, offerings of food and flowers, and libations at the cemetery are other reminders of Pharaonic Egypt. [Source: Saphinaz-Amal Naguib, University of Oslo, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Copts go to the cemetery on fixed dates—specifically, the third day after death, after the rituals of “taking away the mattings” and “delivering the soul of the dead” have been carried out, then on the seventh, fifteenth, and fortieth day after death. Other periodic visits to the dead take place on the Coptic New Year (cayd el-nayruuz), on Nativity (cayd el-miilaad), on the Day of Immersion (yawm el-ghitaas), on Palm Sunday (‘ahad el-sacaf), during Pentecost (el-khamsiin or cayd el-cansara), and during pilgrimages and mulids. It is especially women who carry out these visits, or tuluuc (more commonly known as talca). Their attitudes resonate with those attributed to the goddesses Isis and Nephthys. Like them, they cry for the dead, lament over the corpse, bring offerings of food and flowers, and make libations of water.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024