Home | Category: Religion and Gods

MAGIC IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Magic pervaded many aspects of life in ancient Egypt. It was invoked for everyday healing, in ceremonies for the dead and for court intrigues like the assassination attempt of Pharaoh Ramesses III. Artifacts with links to magic include an ivory wand in the British Museum showing 'fearsome' deities being commanded by a magician; a headrest of a scribe with protective deities including the god Bes, who warded off evil demons as its user slept; and magical cippus stelae showing the infant god Horus overcoming dangerous animals and reptiles.

According to the Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology: To people throughout history, Egypt has seemed the very birthplace of magic. In Egypt the peoples of the ancient world found a magical system more sophisticated than any other that was known. The emphasis on death and the care of the human corpse, central to Egyptian religion, seemed to other cultures to be suggestive of magic practice. As with all other systems, the Egyptians' magic consisted of two different kinds: that which was supposed to benefit either the living or the dead; and, that which has been known throughout the ages as black magic or necromancy. [Source: Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, The Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“The contents of the Westcar Papyrus show that as early as the fourth dynasty the working of magic was a recognineolithic times. Egyptians used magic for numerous purposes, including exorcizing storms and protecting themselves and their loved ones against wild beasts, poison, disease, wounds, and the ghosts of the dead. Throughout the centuries, the practice varied considerably evan as the principal means of operation remained the same: amulets; spells; magic books, pictures, and formulas; magical names and ceremonies; and the general apparatus of the occult sciences. The use of amulets was one of the most potent methods of guarding against any misfortune.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TEMPLE WORKERS, WEALTH AND PROPERTY africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PRIESTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

WORSHIP AND RITUALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SACRIFICES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: PIGS, BULLS AND POSSIBLY HUMANS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PERSONAL RELIGION IN ANCIENT EGYPT: VOTIVE OFFERINGS AND DOMESTIC RELIGIOUS PRACTICES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CULTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ASTROLOGY, SUPERSTITIONS, CURSES AND AMULETS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Heka: The Practices of Ancient Egyptian Ritual and Magic” by David Rankine (2006) Amazon.com;

“Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Geraldine Pinch, a professor of Egyptology at Cambridge University (1994) Amazon.com;

“Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Sacred Magic of Ancient Egypt: The Spiritual Practice Restored”

by Rosemary Clark (2021) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Egyptian Magical Formularies: Text and Translation, Vol. 1"

by Christopher A. Faraone and Sofía Torallas Tovar (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Magic: A Hands-On Guide” by Christina Riggs (2020) Amazon.com;

“Amulets of Ancient Egypt” by Carol Andrews (1994) Amazon.com;

“Through a Glass Darkly: Magic, Dreams and Prophecy in Ancient Egypt” (2023)

by Kasia Szpakowska (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Magic” by Eleanor L. Harris and Normandi Ellis (2016) Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Temple Ritual: Performance, Patterns, and Practice” by Katherine Eaton (2013) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths,and Personal Practice” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

“Gods Priests & Men” by Alan Lloyd Amazon.com;

“The Priests of Ancient Egypt” by Serge Sauneron, David Lorton, Jean-Pierre Corteggiani (2000) Autho Amazon.com;

Heka

Dr Geraldine Pinch of Oxford University wrote for the BBC: “In Egyptian myth, magic (heka) was one of the forces used by the creator to make the world. Through heka, symbolic actions could have practical effects. All deities and people were thought to possess this force in some degree, but there were rules about why and how it could be used. [Source: Dr Geraldine Pinch, BBC, February 17, 2011. Dr Pinch taught Egyptology at Cambridge University and is now a member of the Oriental Institute, Oxford University. Her books include Votive Offerings to Hathor (Griffith Institute) and Handbook of Egyptian Mythology (ABC-Clio) |::|]

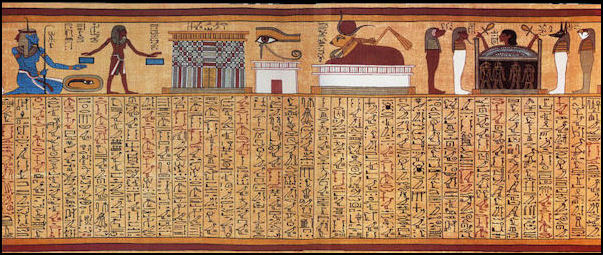

“All Egyptians expected to need heka to preserve their bodies and souls in the afterlife, and curses threatening to send dangerous animals to hunt down tomb-robbers were sometimes inscribed on tomb walls. The mummified body itself was protected by amulets, hidden beneath its wrappings. Collections of funerary spells-such as the Coffin Texts and the Book of the Dead-were included in elite burials, to provide esoteric magical knowledge. |::|

“The dead person's soul, usually shown as a bird with a human head and arms, made a dangerous journey through the underworld. The soul had to overcome the demons it would encounter by using magic words and gestures. There were even spells to help the deceased when their past life was being assessed by the Forty-Two Judges of the Underworld. Once a dead person was declared innocent they became an akh, a 'transfigured' spirit. This gave them akhw power, a superior kind of magic, which could be used on behalf of their living relatives.” |::|

Magicians in Ancient Egypt

Dr Geraldine Pinch of Oxford University wrote for the BBC: Priests were the main practitioners of magic in pharaonic Egypt, where they were seen as guardians of a secret knowledge given by the gods to humanity to 'ward off the blows of fate'. The most respected users of magic were the lector priests, who could read the ancient books of magic kept in temple and palace libraries. In popular stories such men were credited with the power to bring wax animals to life, or roll back the waters of a lake. [Source: Dr Geraldine Pinch, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Real lector priests performed magical rituals to protect their king, and to help the dead to rebirth. By the first millennium B.C., their role seems to have been taken over by magicians (hekau). Healing magic was a speciality of the priests who served Sekhmet, the fearsome goddess of plague. |::|

“Lower in status were the scorpion-charmers, who used magic to rid an area of poisonous reptiles and insects. Midwives and nurses also included magic among their skills, and wise women might be consulted about which ghost or deity was causing a person trouble. |::|

“Amulets were another source of magic power, obtainable from 'protection-makers', who could be male or female. None of these uses of magic was disapproved of-either by the state or the priesthood. Only foreigners were regularly accused of using evil magic. It is not until the Roman period that there is much evidence of individual magicians practising harmful magic for financial reward.” |::|

Magical Techniques in Ancient Egypt

Voodoo-doll like Wax figures were used to represent the bodies of persons to be cursed or harmed. Models of all kinds indicated the belief that the physical force directed against them might injure the person or animal they represented. Ancient Egyptians believed that it was possible to transmit to the image of any person or animal the soul of the being that it represented. According to the Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsycholog: The Westcar Papyrus related how a soldier who had fallen in love with a governor's wife was swallowed by a crocodile when bathing, the saurian being a magical replica of a waxen one made by the lady's husband. In the official account of a conspiracy against Rameses III (1200B.C.E.) the conspirators obtained access to a magical papyrus in the royal library and employed its instructions against the king with disastrous effects to themselves. Others made waxen figures of gods and of the king for the purpose of slaying the latter. [Source: Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, The Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Dr Geraldine Pinch of Oxford University wrote for the BBC: “Dawn was the most propitious time to perform magic, and the magician had to be in a state of ritual purity. This might involve abstaining from sex before the rite, and avoiding contact with people who were deemed to be polluted, such as embalmers or menstruating women. Ideally, the magician would bathe and then dress in new or clean clothes before beginning a spell. |::|

“Metal wands representing the snake goddess Great of Magic were carried by some practitioners of magic. Semi-circular ivory wands-decorated with fearsome deities-were used in the second millennium B.C. The wands were symbols of the authority of the magician to summon powerful beings, and to make them obey him or her. |::|

“Only a small percentage of Egyptians were fully literate, so written magic was the most prestigious kind of all. Private collections of spells were treasured possessions, handed down within families. Protective or healing spells written on papyrus were sometimes folded up and worn on the body. |::|

Spells in Ancient Egypt

According to the Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology: ““Many books of magic in Egypt contained spells and other formulas for exorcism and necromantic practice. The priestly caste who compiled those necromantic works was known as Kerheb, or "scribes of the divine writings" Even the sons of pharaohs did not disdain to enter their ranks. People believed that all supernatural beings, good and evil, possessed a hidden name. If a person knew the name he could compel that being to do his will. The name was as much a part of the man as his body or soul. The traveler through Amenti not only had to tell the divine gods their names. They also had to prove that he knew the names of a number of the supposedly inanimate objects in the dreary underworld. [Source: Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, The Gale Group Inc., 2001]

The simplest type of magic spell used in Egypt was that in which the exorcist threatened the evil principle, or assured it that he could injure it. In general, the magician requested the assistance of the gods, or pretended that he was a god. Invocations, when written, were usually accompanied by a note to the effect that the formula had once been employed successfully by a god—perhaps by a deified priest.

“An incomprehensible and mysterious jargon was employed that was supposed to conceal the name of a certain deity. This deity was thus compelled to do the will of the sorcerer. These gods were usually the gods of foreign nations. The invocations themselves appear to be attempts at various foreign idioms, likely employed because they sounded more mysterious than the native speech. Great stress was laid upon the proper pronunciation of these names. Misprounciation was accountable for failure in all cases. The Book of the Dead contains many such "words of power." These were intended to assist the dead in their journey in the underworld of Amenti.

Dr Geraldine Pinch of Oxford University wrote for the BBC: “A spell usually consisted of two parts: the words to be spoken and a description of the actions to be taken. To be effective all the words, especially the secret names of deities, had to be pronounced correctly. The words might be spoken to activate the power of an amulet, a figurine, or a potion. These potions might contain bizarre ingredients such as the blood of a black dog, or the milk of a woman who had born a male child. Music and dance, and gestures such as pointing and stamping, could also form part of a spell.” |::| . |::|

See Separate Article: HYMNS, RITUALS AND SPELLS FROM THE BOOK OF THE DEAD AND OTHER EGYPTIAN RELIGIOUS TEXTS africame.factsanddetails.com

Ideas Behind Ancient Egyptian Magic Spells

The magical spells used by the Egyptians were founded chiefly on the idea that a magician could resurrect some incident in the history of the gods, which had brought good luck to one of the heavenly beings. In order to reproduce the same good luck he would imagine that he himself represented that god, and he would therefore repeat the words the god had spoken in that incident; words which had formerly been so effective would, he felt sure, be again of good service. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

For instance, if he desired to cool or heal a burn, after using as a remedy “the milk of a woman who had borne a son," he would say over it the following formula: “My son Horus, it burns on the mountain, no water is there, I am not there, fetch water from the bank of the river to put out the fire. " These words were evidently spoken by Isis in a divine legend. A fire had broken out, and the goddess called anxiously to her son Horus to fetch water. As this cry for help had formerly produced the means whereby the fire on the mountain was extinguished, it was to be hoped that the same words in the mouth of the magician would stop the burning of the wound.

It was the same with the following exorcism, which was spoken over the smell-seeds and over the inevitable “milk of a woman who has borne a son," in order to make these medicines effective against a cold. “Depart cold, son of a cold, thou who breakest the bones, destroyest the skull, partest company with fat, makest ill the seven openings in the head! The servants of Re beseech Thoth — ' Behold I bring thy recipe to thee, thy remedy to thee: the milk of a woman who has borne a son and the smell-seeds. Let that drive thee away, let that heal thee; let that heal thee, let that drive thee away. Go out on the floor, stink, stink! stink, stink! ' “This catarrh incantation is taken from a myth concerning the old age and the illnesses of the sun-god. Ra is suffering from a cold, which confuses his head; his attendants beseech the god of learning for a remedy; the god brings it immediately and announces to the illness that it must yield to it. In these magical formulae the magician repeated the words of the god, and through them he exercised the magic power of the god; in other cases it would suffice for him to designate himself as that god, whose power he wished to possess.

The magic formulae were naturally most effective when they were said aloud, but they were of use also even when they were written; this accounts for the zeal with which the magic formulae for the deceased were written everywhere in the tomb, and on the tomb furniture —-the greater the number of times they were written, the more certainly they took effect.

Magic as a Form of Protection in Ancient Egypt

Dr Geraldine Pinch of Oxford University wrote for the BBC: “Angry deities, jealous ghosts, and foreign demons and sorcerers were thought to cause misfortunes such as illness, accidents, poverty and infertility. Magic provided a defence system against these ills for individuals throughout their lives. [Source: Dr Geraldine Pinch, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

magic wands

“Stamping, shouting, and making a loud noise with rattles, drums and tambourines were all thought to drive hostile forces away from vulnerable women, such as those who were pregnant or about to give birth, and from children-also a group at risk, liable to die from childhood diseases. |::|

“Some of the ivory wands may have been used to draw a protective circle around the area where a woman was to give birth, or to nurse her child. The wands were engraved with the dangerous beings invoked by the magician to fight on behalf of the mother and child. They are shown stabbing, strangling or biting evil forces, which are represented by snakes and foreigners. |::|

“Supernatural 'fighters, such as the lion-dwarf Bes and the hippopotamus goddess Taweret, were represented on furniture and household items. Their job was to protect the home, especially at night when the forces of chaos were felt to be at their most powerful. |::|

“Bes and Taweret also feature in amuletic jewellery. Egyptians of all classes wore protective amulets, which could take the form of powerful deities or animals, or use royal names and symbols. Other amulets were designed to magically endow the wearer with desirable qualities, such as long life, prosperity and good health.” |::|

Ancient Egyptian Spells to Ward Off Snakes

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Archaeologists have unearthed the unusual tomb of an Egyptian dignitary who was interred in the necropolis at Abusir around 2,500 years ago. The ornately decorated burial chamber, which was found at the bottom of a 45-foot-deep shaft, belonged to a man named Djehutyemhat, who served as a royal scribe. Although the grave’s artifacts were looted, the room’s rich decoration was preserved. The walls are covered with depictions of gods and textual passages intended to aid the deceased’s transition to the afterlife, and the ceiling has a carved scene of the sun god’s journey across the sky. An image of Imentet, goddess of the West, who served as Djehutyemhat’s guide and symbolic mother, was carved inside his sarcophagus. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, March/April 2024]

The scribe also had another layer of protection. A set of magical spells meant to ward off serpents and snakebites was inscribed on the chamber’s entrance wall. “Snakes were one of several ubiquitous dangers characterizing the ancient Egyptian landscape,” says archaeologist Miroslav Bárta of Charles University. “Egyptians conceptualized their afterlife as similar, if not identical, to their earthly existence, so dangers in this world were supposed to occur in the afterlife as well. Precautions in the form of protective spells had to be taken.”

Analysis of Djehutyemhat’s skeletal remains suggests that the scribe was around 25 years old when he died, and that his profession had taken a toll on his body, as his vertebrae showed signs of severe wear. “Being appointed as an official in state offices took decades off your life,” Bárta says. “The sitting pose of a professional scribe was with legs crossed and torso bent forward to read and write. This led to chronic problems with the cervical vertebrae, hips, knees, ankles, and wrists, and quite often very painful arthrosis.”

Spells to Ward Off Crocodiles

It was said that if the following words were said over the water crocodiles to be as terrified as if the the gods themselves had passed by that way.

Thou art not above me I am Amun.

I am Hathor, the beautiful slayer.

I am the prince, the of the sword.

Raise not thyself — I am Mont, etc.

It was of course especially effective if instead of using the usual name of the god, the magician could name his real name, that special name possessed by each god and each genius in which his power resided. He who knew this name, possessed the power of him who bore it. There is a story about how the goddess Isis, the great enchantress, persuaded the sun-god to reveal to her his secret name, and thus became as powerful as he was himself

It was said that the following incantation, which refers to this name, would work even better against the crocodiles than the one quoted above:

“I am the chosen one of million, who proceeds from the kingdom of light, Whose name no one knows. If his name be spoken over the stream It is obliterated.

If his name be spoken over the land It causes fire to arise. I am Shu, the image of Ra, Who sits in his eye.

If any one who is in the water (such as a crocodile) open his mouth. If he strike (?) his arms,

Then will I cause the earth to fall into the stream And the South to become the North And the earth to turn round. "

As we see, the magician guards himself from actually pronouncing the real name of Shu; he only threatens to name it, and therewith to unhinge the world. Incidentally indeed he even threatens the god himself with the mention of his secret name, to whom the revelation would be fatal. Further, he who in terror of the monsters of the water should repeat the following incantation four times:

“Come to me, come to me, thou image of the eternity of eternities! Thou Khnum, son of the One! Conceived yesterday, born to-day. Whose name I know,"

the divine being whom he called, who “has seventy-seven eyes and seventyseven ears," “would certainly come to his help.

There was another way of perpetuating the power of the magic formulae; they were recited over objects of a certain kind, which were thus invested with a lasting magical virtue. Thus the above crocodile incantations might be recited over an egg made of clay; if then the pilot of the boat carried this egg in his hand, all the terrible animals that had emerged from the stream would again sink immediately into the water. In the same way it was possible to endow figures of paper or of wax with magical efficacy; if such were brought secretly into the house of an enemy, they would spread sickness and weakness there. ''

Procuring Dreams in Ancient Egypt

Interpreting dreams was an art practiced by magicians in Egypt. The Egyptian magician procured dreams for his clients by drawing magic pictures and reciting magic words. The following formulas for producing a dream are taken from British Museum Papyrus, no. 122, lines 64ff and 359ff: [Source: Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, The Gale Group Inc., 2001]

"To obtain a vision from the god Bes: Make a drawing of Bes, as shewn below, on your left hand, and envelope your hand in a strip of black cloth that has been consecrated to Isis and lie down to sleep without speaking a word, even in answer to a question. Wind the remainder of the cloth round your neck. The ink with which you write must be composed of the blood of a cow, the blood of a white dove, fresh frankincense, myrrh, black writing ink, cinnabar, mulberry juice, rain-water, and the juice of wormwood and vetch. With this write your petition before the setting sun, saying, 'Send the truthful seer out of the holy shrine, I beseech thee Lampsuer, Sumarta, Baribas, Dardalam, Iorlex: O Lord send the sacred deity Anuth, Anuth, Salbana, Chambré, Breith, now, now, quickly, quickly. Come in this very night.'

“"To procure dreams: Take a clean linen bag and write upon it the names given below. Fold it up and make it into a lamp-wick, and set it alight, pouring pure oil over it. The word to be written is this: "Armiuth, Lailamchouch, Arsenophrephren, Phtha, Archentechtha." Then in the evening, when you are going to bed, which you must do without touching food (or, pure from all defilement), do thus: Approach the lamp and repeat seven times the formula given below: then extinguish it and lie down to sleep. The formula is this: "Sachmu…epaema Ligotereench: the Aeon, the Thunderer, Thou that hast swallowed the snake and dost exhaust the moon, and dost raise up the orb of the sun in his season, Chthetho is the name; I require, O lords of the gods, Seth, Chreps, give me the information that I desire."

Magic Used for Healing in Ancient Egypt

Dr Geraldine Pinch of Oxford University wrote for the BBC: “Magic was not so much an alternative to medical treatment as a complementary therapy. Surviving medical-magical papyri contain spells for the use of doctors, Sekhmet priests and scorpion-charmers. The spells were often targeted at the supernatural beings that were believed to be the ultimate cause of diseases. Knowing the names of these beings gave the magician power to act against them. [Source: Dr Geraldine Pinch, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Since demons were thought to be attracted by foul things, attempts were sometimes made to lure them out of the patient's body with dung; at other times a sweet substance such as honey was used, to repel them. Another technique was for the doctor to draw images of deities on the patient's skin. The patient then licked these off, to absorb their healing power. |::|

“Many spells included speeches, which the doctor or the patient recited in order to identify themselves with characters in Egyptian myth. The doctor may have proclaimed that he was Thoth, the god of magical knowledge who healed the wounded eye of the god Horus. Acting out the myth would ensure that the patient would be cured, like Horus. Collections of healing and protective spells were sometimes inscribed on statues and stone slabs (stelae) for public use. A statue of King Ramesses III (c.1184-1153 B.C.), set up in the desert, provided spells to banish snakes and cure snakebites. |::|

“Some have inscriptions describing how Horus was poisoned by his enemies, and how Isis, his mother, pleaded for her son's life, until the sun god Ra sent Thoth to cure him. The story ends with the promise that anyone who is suffering will be healed, as Horus was healed. The power in these words and images could be accessed by pouring water over the cippus. The magic water was then drunk by the patient, or used to wash their wound.” |::|

Magic Wands in Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egyptian “magic wands” looked sort of like boomerangs and often contained images of demons. Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Some 230 of these curved objects, usually made of highly polished hippopotamus ivory and resembling the shape of tusks, are known. Though many are worn from use, it’s clear that most were incised with depictions of demons wielding knives. Some Egyptologists believe the ancient Egyptians imagined the wands themselves as magic knives. High-status Egyptians who could afford them wielded these powerful instruments against supernatural forces by calling upon the power of the demons to ward off evil. It’s possible the Egyptians of the Middle Kingdom developed these wands as a response to the period of religious and ideological uncertainty that followed the collapse of the Old Kingdom (ca. 2649–2150 B.C.). With the memory that traditional centers of power and religion had been in disarray, perhaps these wands gave some high-ranking Egyptians the confidence to tap into the power of demons and keep the forces of chaos at bay. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2022]

“The so-called palettes, originally thought to be used for the mixing of paint, are now known to have been amulets inscribed with words of power and placed on the breasts of the dead in neolithic times. The menat was worn, or held, with the sistrum (a musical instrument) by gods, kings, and priests and was supposed to bring joy and health to the wearer. It represented the vigor of the two sexes. [Source: Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, The Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Magic Bricks in Ancient Egypt

Virginia L. Emery of the University of Chicago wrote: “For the ancient Egyptians, bricks not only were construction material—the building blocks of physical structures—but also were objects that could be imbued with symbolic significance. During the New Kingdom, four magic mud-bricks, one for each cardinal direction, came to be included in tombs as an element of funerary equipment and were recovered from the royal tombs of Thutmose IV, Amenhotep III, Tutankhamen, Ay, Horemheb, Ramesses I, Sety I, and Ramesses II, as well as from the tombs of queens Sitra, Nefertari, and Bentanti; they could also be included in private tombs. [Source: Virginia L. Emery, University of Chicago, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“These magic bricks were inscribed in hieratic with Spell 151 from the Book of the Dead and were usually installed in niches carved in the walls of the burial chamber. Each brick was provided with a hole in it to fit an amulet, usually a Dd-amulet of blue faience and gold on the western brick, a recumbent Anubis of unbaked clay on the eastern brick, a small wooden shabti-like statuette on the northern brick, and a reed with a wick in it, probably a torch or flame of some kind, on the southern brick. The bricks and amulets were provided as an apotropaic feature of the funerary equipment, acting as the protectors of the Osiris residing in the tomb.

“As well as occurring in funerary contexts, bricks with magically protective qualities were also employed during birthings. Long known from textual and representational sources, a single example of a decorated birth brick was discovered during the course of excavations at South Abydos in the Middle Kingdom town adjacent to (and probably attached to/dependent on) the memorial complex of Senusret III. The brick is decorated with a polychrome scene on the base depicting a mother holding her baby and attended by two females; the entire scene is flanked by Hathor-headed divine standards. Anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures, which are usually shown protecting the sun god Ra during his daily rebirth on the eastern horizon, decorate the preserved sides of the brick, creating explicitly magical scenes of a type known from Middle Kingdom “magical knives,” but also linking to beliefs concerning funerary practices and the afterlife.”

Egyptian Spells with Christian Overtones

In 2014, after decades to trying, researchers deciphered an Egyptian codex that turned out to be a book of spells — with some pertaining to love, success in business, cures for diseases such a black jaundice and exorcisms — along with instructions on how to do them. Among the spells were one for befriending an enemy and ones for destroying him. [Source: Jana Louise Smit, Listverse, May 15, 2016, Live Science November 24, 2014]

The 1,300-year-old. beautifully-illustrated book is written in Coptic, an Egyptian language and is made of bound pages of parchment — a type of book known as a codex. Named the “Handbook of Ritual Power” by researchers, it contains references to Jesus as well as an unknown godlike figure called “Bakthiotha.” Some invocations are linked to the extinct Sethian religious movement, which describes Seth (third son of Adam and Eve) as “the living Christ.” Researchers believe the document shows some of the last gasps of Pharaonic religion transitioning Coptic Christianity.” The owner of the book and where it originated is a mystery. The Coptic writing style points to the ancient Roman-Egyptian city of Hermopolis as a possible candidate.

“It is a complete 20-page parchment codex, containing the handbook of a ritual practitioner,” Malcolm Choat and Iain Gardner, professors at Macquarie University and the University of Sydney, respectively, wrote. The ancient book “starts with a lengthy series of invocations that culminate with drawings and words of power... “These are followed by a number of prescriptions or spells to cure possession by spirits and various ailments, or to bring success in love and business.”

Book of the Dead spell

To to subjugate someone, the codex says, you have to say a magical formula over two nails and then “drive them into his doorpost, one on the right side (and) one on the left.” The opening of the codex, which refers to Baktiotha, reads: “I give thanks to you and I call upon you, the Baktiotha: The great one, who is very trustworthy; the one who is lord over the forty and the nine kinds of serpents,” according to the translation. “The Baktiotha is an ambivalent figure,” Choat and Gardner said at a conference before their book on the codex was published. “He is a great power and a ruler of forces in the material realm.” Historical records indicate that church leaders regarded the Sethians as heretics, and by the 7th century, the Sethians were either extinct or dying out.

A large A.D. 5th century papyrus sheet, written in Coptic, was discovered in 1934 at the pyramid of Senusret I at Lisht in Lower Egypt by a team sponsored by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and translated in the 2010s by Michael Zellmann-Rohrer of the University of Oxford. It consists of a prayer, some of which would have been inscribed on a physical object to make what is known as a textual amulet. This is a well-known practice in the Egyptian tradition, but somewhat more unusual in a Christian context. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2018]

According to Archaeology magazine:“The text quotes at length from a prayer by Seth, a son of Adam and Eve, which is believed to have caused a theophany, or an appearance of God. “The user wants, if not a theophany, then at least the full attention of the divinity,” says Zellmann-Rohrer, “so the best way to achieve that will be to repeat the prayer that Seth is supposed to have used.” Another notable feature of the text is that it refers to an angelic power several times as “the one who presides over the Mountain of the Murderer.” Zellmann-Rohrer says this is likely to be a reference to an alternate version of the story of Abraham and Isaac from the Book of Genesis in which Abraham goes ahead with the sacrifice of his son rather than being stopped by God at the last minute.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024