Home | Category: Religion and Gods

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN SUPERSTITIONS

The superstition that spilling salt is bad luck and the custom of throwing salt could cancel bad luck was practiced by the ancient Sumerians, Egyptians, Assyrians and later the Romans and Greeks. It is believed to have been practiced since 3500 B.C.

Walking under a ladder is superstition that has been dated to 3000 B.C. in Egypt. Ladders were considered good luck but a leaning ladder formed a pyramid-like triangle that was considered to be the sacred realm of the gods and was sacrilegious for commoners to enter. Fear of the "evil eye" is a superstition found in many cultures and is quite common in the Mediterranean. Egyptians wore kohl, the world's first mascara, in a circle or oval around their eyes, in part to ward off the evil eye.

The act of writing was believed to have magical powers and hieroglyphic were thought to possess the power of the object that they represented. Positive images were thought to bring positive rewards. Negative images such as scorpions were often intentionally left unfinished in tombs so their negative power would not affect the dead in their journey to the afterlife.

Fifth Century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: Their divination is ordered thus: — the art is assigned not to any man but to certain of the gods, for there are in their land Oracles of Heracles, of Apollo, of Athene, of Artemis, or Ares, and of Zeus, and moreover that which they hold most in honour of all, namely the Oracle of Leto which is in the city of Buto. The manner of divination however is not established among them according to the same fashion everywhere, but is different in different places. The art of medicine among them is distributed thus: — each physician is a physician of one disease and of no more; and the whole country is full of physicians, for some profess themselves to be physicians of the eyes, others of the head, others of the teeth, others of the affections of the stomach, and others of the more obscure ailments. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A.D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

In 1972 a 3,300 year old ancient Egyptian outpost was discovered on the Gaza Strip. The Bedouin, who helped archaeologists locate it used a long screw driver like a divining rob to find it. When the archaeologists asked the man to explain how he performed his magic, the man said enigmatically, "Some days it's honey, some days onions." But surprising on a day he predicted beforehand would be honey the site was discovered. [Source: Trude Dothan, National Geographic , December 1982]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TEMPLE WORKERS, WEALTH AND PROPERTY africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PRIESTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

WORSHIP AND RITUALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SACRIFICES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: PIGS, BULLS AND POSSIBLY HUMANS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PERSONAL RELIGION IN ANCIENT EGYPT: VOTIVE OFFERINGS AND DOMESTIC RELIGIOUS PRACTICES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CULTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MAGIC IN ANCIENT EGYPT: SPELLS, WANDS AND DREAMS africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Amulets of Ancient Egypt” by Carol Andrews (1994) Amazon.com;

“Through a Glass Darkly: Magic, Dreams and Prophecy in Ancient Egypt” (2023)

by Kasia Szpakowska (2023) Amazon.com;

“Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World” by John G. Gager (1999) Amazon.com;

:Amulets and Superstitions: the Original Texts With Translations and Descriptions of a Long Series of Egyptian, Sumerian, Assyrian, Hebrew, Christian, ... With Chapters on the Evil Eye” by E A Wallis Budge ((1857-1934) Amazon.com;

“Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Geraldine Pinch, a professor of Egyptology at Cambridge University (1994) Amazon.com;

“Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Magic” by Eleanor L. Harris and Normandi Ellis (2016) Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Temple Ritual: Performance, Patterns, and Practice” by Katherine Eaton (2013) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths,and Personal Practice” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

“Gods Priests & Men” by Alan Lloyd Amazon.com;

“The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Religion an Interpretation” by Henri Frankfort (1948, 2011) Amazon.com;

Lucky and Unlucky Days in Ancient Egypt

The belief in luck and unlucky days appears to have been very strong in the New Kingdom, often based on a good or bad mythological incident took place on that day. For example, the 1st of Mechir, on which day the sky was raised, and the 27th of Athyr, when Horus and Seth concluded peace together and divided the world between them, were lucky days. On the other hand the 14th of Tybi, on which Isis and Nephthys mourned for Osiris, was an unlucky day. The five additional days of the year (hryw rnpt) were interpreted as ‘bad’ and full of dangers. It was necessary to say special spells on those days and do not undertake any works.

Herodotus wrote: Besides these things the Egyptians have found out also to what god each month and each day belongs, and what fortunes a man will meet with who is born on any particular day, and how he will die, and what kind of a man he will be: and these inventions were taken up by those of the Greeks who occupied themselves about poesy. Portents too have been found out by them more than by all other men besides; for when a portent has happened, they observe and write down the event which comes of it, and if ever afterwards anything resembling this happens, they believe that the event which comes of it will be similar.

With the unlucky days, which fortunately were less in number than the lucky days, they distinguished different degrees of ill-luck. Some were very unlucky, others only threatened ill-luck, and many like the 17th and the 27th of Koiak were partly good and partly bad according to the time of day. Lucky days might as a rule be disregarded. At most it might be as well to visit some specially renowned temple, or to “celebrate a joyful day at home," but no particular precautions were really necessary; and above all it was said: “what thou also seest on the day is lucky." [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

It was quite otherwise with the unlucky and dangerous days, which imposed so many and such great limitations on people, that those who wished to be prudent were always obliged to bear them in mind when determining on any course of action. Certain conditions were easy to carry out. Music and singing were to be avoided on the 14th Tybi, the day of the mourning for Osiris, and no one was allowed to wash on the 16th Tybi; whilst the name of Set might not be pronounced on the 24th of Pharmuthi. Fish was forbidden on certain days; and what was still more difficult in a country so rich in mice, on the 12th Tybi no mouse might be seen.

The most tiresome prohibitions however were those which occurred not infrequently, namely, those concerning work and going out: for instance, four times in Paophi the people had to “do nothing at all," and five times to sit the whole day or half the day in the house; and the same rule had to be observed each month. Even the most cautious could not avoid all the ill-luck that unlucky days could bring, so that the knowledge of them was ever an anxiety to them. It was impossible to rejoice if a child were born on the 23rd of Thoth; the parents knew it could not live. Those born on the 20th of Koiak would become blind, and those born on the 3rd of Koiak, deaf

Ancient Egyptian Astrology

The Egyptians refined the Babylonian system of astrology and the Greeks shaped it into its modern form. Astrology as we know it originated in Babylon. It developed out of the belief that since the Gods in the heavens ruled man's fate, the stars could reveal fortunes and the notion that the motions of the stars and planets control the fate of people on earth. The motions of the stars and planets are mainly the result of the earth’s movement around the sun, which causes: 1) the sun to move eastward against the background of the constellations; 2) the planets and moon to shift around the sky; and 3) causes different constellations to rise from the horizon at sunset different times of the year.

In ancient times astrology and astronomy were the same thing. The Babylonians were the first people to apply myths to constellations and astrology and describe the 12 signs of the zodiac. The Greeks and Romans borrowed some of their myths from the Babylonians and invented their own. The word astrology (and astronomy) are derived from the Greek word for "star."

The names and shapes of many the constellations are believed to date to Sumerian times because the animals and figures chosen held a prominent place in their lives. It is thought that if the constellations originated with the the Egyptians were would ibises, jackals, crocodiles and hippos — animals in their environment — rather than goats and bulls. If they came from India why isn’t there a tiger or a monkey. To the Assyrians the constellation Capricorn was munaxa (the goat fish).

The Greeks added names of heroes to the constellations. The Romans took these and gave them the Latin names we use today. Ptolemy listed 48 constellations. His list included ones in the southern hemisphere, which he and the Mesopotamians, Egyptians, Greeks and Romans couldn’t see.

See Separate Article: ASTRONOMY IN ANCIENT EGYPT: ASTROLOGY STARS, TABLES, OBSERVATORY africame.factsanddetails.com

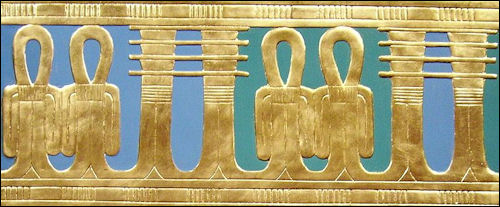

sacred knots

Magic in Ancient Egypt

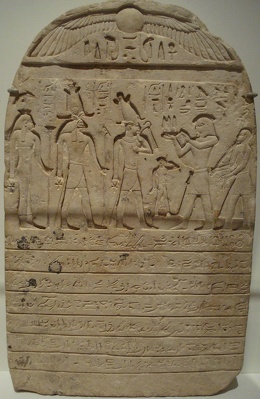

Magic pervaded many aspects of life in ancient Egypt. It was invoked for everyday healing, in ceremonies for the dead and for court intrigues like the assassination attempt of Pharaoh Ramesses III. Artifacts with links to magic include an ivory wand in the British Museum showing 'fearsome' deities being commanded by a magician; a headrest of a scribe with protective deities including the god Bes, who warded off evil demons as its user slept; and magical cippus stelae showing the infant god Horus overcoming dangerous animals and reptiles.

Dr Geraldine Pinch of Oxford University wrote for the BBC: “In Egyptian myth, magic (heka) was one of the forces used by the creator to make the world. Through heka, symbolic actions could have practical effects. All deities and people were thought to possess this force in some degree, but there were rules about why and how it could be used. [Source: Dr Geraldine Pinch, BBC, February 17, 2011. Dr Pinch taught Egyptology at Cambridge University and is now a member of the Oriental Institute, Oxford University. Her books include Votive Offerings to Hathor (Griffith Institute) and Handbook of Egyptian Mythology (ABC-Clio) |::|]

“All Egyptians expected to need heka to preserve their bodies and souls in the afterlife, and curses threatening to send dangerous animals to hunt down tomb-robbers were sometimes inscribed on tomb walls. The mummified body itself was protected by amulets, hidden beneath its wrappings. Collections of funerary spells-such as the Coffin Texts and the Book of the Dead-were included in elite burials, to provide esoteric magical knowledge. |::|

“The dead person's soul, usually shown as a bird with a human head and arms, made a dangerous journey through the underworld. The soul had to overcome the demons it would encounter by using magic words and gestures. There were even spells to help the deceased when their past life was being assessed by the Forty-Two Judges of the Underworld. Once a dead person was declared innocent they became an akh, a 'transfigured' spirit. This gave them akhw power, a superior kind of magic, which could be used on behalf of their living relatives.” |::|

See Separate Article: MAGIC IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Amulets

In ancient Egypt, amulets were carried by the living and wrapped with mummies. They were even carried by the gods and animals. The mummy of King Tut had 143 of them. Their primary purpose was to attract “sympathetic magic” that would protect the wearer from misfortune and maybe bring some good luck. Amulets were inserted in different stages of the embalming process, each with special spells and incantations to go along with it. Some bore inscriptions and were made of materials, such as gold, faience (a blue stone), lapis lazuli, carnelian, green feldspar, and green jasper.

Diana Craig Patch of The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “An amulet is a small object that a person wears, carries, or offers to a deity because he or she believes that it will magically bestow a particular power or form of protection. The conviction that a symbol, form, or concept provides protection, promotes well-being, or brings good luck is common to all societies: in our own, we commonly wear religious symbols, carry a favorite penny, or a rabbit's foot. In ancient Egypt, amulets might be carried, used in necklaces, bracelets, or rings, and—especially—placed among a mummy's bandages to ensure the deceased a safe, healthy, and productive afterlife. [Source: Diana Craig Patch, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2004 metmuseum.org \^/]

“Egyptian amulets functioned in a number of ways. Symbols and deities generally conferred the powers they represent. Small models that represent known objects, such as headrests or arms and legs, served to make sure those items were available to the individual or that a specific need could be addressed. Magic contained in an amulet could be understood not only from its shape. Material, color, scarcity, the grouping of several forms, and words said or ingredients rubbed over the amulet could all be the source for magic granting the possessor's wish. \^/

“Small representations of animals seem to have functioned as amulets already in the Predynastic Period (ca. 4500–3100 B.C.). In the Old Kingdom (ca. 2649–2150 B.C.), most amulets took an animal form or were symbols (often based on hieroglyphs), although generalized human forms occurred. During the Old Kingdom some amulet appears to have consisted of two stones or pieces of wood stuck through each other, and later took the form of a heart, " or a four-cornered shield with mystic figures, decorated at the top with a little hollow. Amulets depicting recognizable deities begin to appear in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.), and the New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 B.C.) showed a further increase in the range of amulet forms. With the Third Intermediate Period (ca. 1070–712 B.C.), there was an explosion in the quantity of amulets, and many new types, especially deities, appeared.” \^/

amulets

Different Types of Ancient Egyptian Amulets

Amulets with protective cobras, “ba” (winged symbols of the soul), “re” (sun disk), ankhs, and scarabs were popular. There were amulets for limbs, organs and other body parts and ones derived from the hieroglyphics for “good.” “truth.” and “eternity.” Hearts, hands and feet were often found on mummies in places where the real body parts were normally found, the idea being that they could be offered as substitutes if the real ones were coveted by demons.

There were amulets for at least 50 principal gods and a countless number of local ones. These amulets took the form of the gods themselves or their symbols. Popular ones included Anabus (a jackal), Horus (a falcon), Thoth (an ibis) and Hathor, the Egyptian goddess of love and fertility. The old amulets were found in simple burials dating to 3100 B.C.

The amulet symbolizing udjat (health) — the eye of Horus — connected the wearer with the god Horus, who lost his eye in a cosmic battle with the god Seth and later had the eye restored. The udjat is regarded as one of the most powerful of all amulets, preserving the wearer and making him strong in the afterlife. Tyet amulets of Isis are red in color, symbolizing her blood. They also brought strength and good health to the wearer.

Scarab Amulets

Kathlyn M Cooney of UCLA wrote: “The most common scarab type is the scarab amulet, so ubiquitous that it is usually referenced in the Egyptological and archaeological literature simply as “scarab”. The beetle form was ideal for use as an amulet. Most scarab amulets are quite small, measuring between 10 mm and 50 mm in length. They are ovoid in shape, the back of the amulet depicting the head and folded wings of the insect and the sides depicting the legs. The scarab amulet is usually pierced longitudinally, so that the owner could wear the object as a ring, necklace, or bracelet. The blank oval underside of the scarab amulet was an excellent location for the inscription of personal names, kings’ names, apotropaic sayings, geometric designs, or figural representations. The scarab amulet could be carved from a variety of stones, including costly amethyst, jasper, carnelian, and lapis lazuli, or from less expensive stones, such as steatite, which was usually glazed. A great many scarab amulets were molded from faience, especially in the New Kingdom. The earliest scarab amulets are dated stylistically to the 6th Dynasty; most early examples are uninscribed. The first scarab seals, bearing the name and title of the owner, developed in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.). The scarab’s use continued in ancient Egypt until the Ptolemaic Period (304–30 B.C.), although production after the reign of Ramses III was limited. The so-called “scaraboid” also belongs to this class of object and describes any amulet carved in the standard ovoid shape but depicting an animal, such as a goose, cat, or frog, rather than a beetle.”[Source: Kathlyn M Cooney, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“It is quite common to organize scarabs by the type of decoration found on the scarab base. The first type of scarab base decoration includes examples ranging in date from the Middle Kingdom through the Late Period, depicting apotropaic and divine iconography, including images of gods and so-called good- luck sayings. This group also includes scarabs from the New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period that are particularly associated with the god Amen and the many cryptographic writings of this god’s name.

“The second type of scarab base includes rulers’ names, epithets, and images, and these examples also date from the Middle Kingdom through the Late Period. The scarab represented the rebirth of the sun god and was therefore intimately associated with cycles of masculine royal renewal and, by extension, Egyptian political power systems. Because of the association of the king and the sun god, scarabs were often inscribed with the names and/or depictions of the king (either currently reigning or deceased). In many ways the scarab was meant to be a gendered object. The word xpr, when used as a noun, is masculine, and most iconography on the underside of scarabs revolves around the masculine political world—of kings and courtiers. This is not to say that a scarab amulet could not depict or be owned by a woman, just that it was more representative of masculine spheres of power and kingship.

“A third category of scarab base decoration features non-royal personal names and titles, suggesting the scarab’s use as the owner’s personal seal, a type that reached its height in the Middle Kingdom. Most of these non-royal names and titles belong to holders of elite offices or priesthoods. A fourth decorative group depicts motifs of northwest Asian origin, in addition to foreign adaptations of Egyptian iconography. Many of these scarabs date from the late Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period (the period of Hyksos domination). Others date to the New Kingdom, when Egypt’s empire reached its apex.

“A fifth scarab amulet group features geometric and stylized patterns, many of them dating to the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period. Most common within this group are abstract geometric, scroll, spiral, woven, floral, and even humanoid patterns. It should also be mentioned that many scarab amulet undersides are uninscribed, and many such examples are made of semi-precious stones.”

Uses of Scarab Amulets

Kathlyn M Cooney of UCLA wrote: “The small size and compact shape of the scarab amulet facilitated mobility and distribution, making the object amenable to various public and private political agendas. In the Middle Kingdom, scarabs were often utilized as seals by non-royal bureaucrats, and many personal names and titles are found on scarabs. Scarabs were manipulated as political tools by the Hyksos kings and their officials during the Second Intermediate Period, when inscribed examples were ostensibly distributed to elites and vassals. During the New Kingdom, scarab amulets and seals were spread throughout the increasingly connected Mediterranean and Near Eastern worlds, and particularly the Levant; as such, the occurrence of kings’ names and figures became especially common. The New Kingdom also saw a blossoming of personal piety in scarab amulet design, when seal iconography increasingly turned towards divine figures, aphorisms, and cryptography. [Source: Kathlyn M Cooney, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“The wide range of scarab decorative genres complicates the issue of scarab meaning and, by extension, function. Scarab amulets fulfilled multiple uses: as administrative tools, as markers of social status, as distributed propaganda messages, or as apotropaic talismans. It is therefore very difficult to place these objects into specific religious, political, or socio-economic categories. Discussion of a given scarab’s decorative genre and function is partly dependent on its production, distribution, and reception—all processes that are difficult to discern in the preserved ancient record, and especially that of unprovenanced scarabs from private collections.

“The small size of the scarab base required the creation and utilization of abbreviated, abstracted, and “loaded” iconography that could be multi-functional and multi- interpretational for the scarab owner. Such iconography provided layers of complexity, because conceptual signs and symbols have multiple grammatical and semiotic meanings, resulting in the overlap of genres and thus scholarly confusion about scarab function. Ultimately, the best explanation of scarab function is that the scarab amulet held a number of meanings and functions simultaneously, depending on the manu- facturer’s intent, the owner’s understanding of the piece, and the occasions of its use. Some of these meanings are amenable to protection and personal piety, while others point to a socio-political use. The scarab amulet’s symbolism was intended to be inclusive and broad, rather than confined to one particular meaning in a given circumstance.”

Oracles in Ancient Egypt

Karnak in Thebes (present-day Luxor is regarded by some scholars as the first oracle center. Its name translates as “'The most perfect of places.” It was said that that all other oracles originated from Karnark and they communicated with one another by using of “homing' doves” that enabled them to “see into the future.” An Omphalus (religious stone artifact) excavated in the sanctuary of the Great Temple of Amon at Karna, by G. A. Reisner supports the Greek traditions of doves flying between Delphi and Karnak. [Source: Ancient Wisdom ancient-wisdom.com/*/]

Two ancient Egyptian texts interpreted as providing evidence of oracles in Karnak read: ‘Ye people from south and north, all ye eyes that see the sun, all ye who come from south and north to Thebes to entreat the lord of gods, come to me! What ye say I shall pass to Amun at Karnak. Say the "offering spell" to me and give me water from that which ye possess. For I am the messenger whom the king has appointed to hear your words of petition and to send up to him the affairs of the Two Lands.’ /*/

And “Ye people of Karnak, ye who wish to see Amun, come to me! I shall report your petitions. For I am indeed the messenger of this god. The king has appointed me to report the words of the Two Lands. Speak to me the "offering spell" and invoke my name daily, as is done to one who has taken a vow.’ /*/

Siwa Oasis in present-day Libya was specifically mentioned in relation to Karnak and Dodona by Herodotus. Alexander the Great went out of his way to consult the Oracle of Amun in 331 B.C. before his conquest of Persia. The King of Persia led an army of 50,000 to destroy the oracle that resulted in the entire army being lost to the desert. /*/

Herodotus on Oracles in Ancient Egypt

The Oracle of Ammon (Amun) was a famous oracle in the Amun Temple in the Siwa Oasis of present-day Libya that visited by Alexander the Great in the 3rd Century B.C. It existed long before that. The Fifth Century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: The answer given by the Oracle of Ammon bears witness in support of my opinion that Egypt is of the extent which I declare it to be in my account... As regards the Oracles both that among the Hellenes and that in Libya, the Egyptians tell the following tale. The priests of the Theban Zeus told me that two women in the service of the temple had been carried away from Thebes by Phoenicians, and that they had heard that one of them had been sold to go into Libya and the other to the Hellenes; and these women, they said, were they who first founded the prophetic seats among the nations which have been named: and when I inquired whence they knew so perfectly of this tale which they told, they said in reply that a great search had been made by the priests after these women, and that they had not been able to find them, but they had heard afterwards this tale about them which they were telling. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A.D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

This I heard from the priests at Thebes, and what follows is said by the prophetesses of Dodona. They say that two black doves flew from Thebes in Egypt, and came one of them to Libya and the other to their land. And this latter settled upon an oak-tree and spoke with human voice, saying that it was necessary that a prophetic seat of Zeus should be established in that place; and they supposed that that was of the gods which was announced to them, and made one accordingly: and the dove which went away to the Libyans, they say, bade the Libyans make an Oracle of Ammon; and this also is of Zeus. The priestesses of Dodona told me these things, of whom the eldest was named Promeneia, the next after her Timarete, and the youngest Nicandra; and the other people of Dodona who were engaged about the temple gave accounts agreeing with theirs.

I however have an opinion about the matter as follows: — If the Phoenicians did in truth carry away the consecrated women and sold one of them into Libya and the other into Hellas, I suppose that in the country now called Hellas, which was formerly called Pelasgia, this woman was sold into the land of the Thesprotians; and then being a slave there she set up a sanctuary of Zeus under a real oak-tree; as indeed it was natural that being an attendant of the sanctuary of Zeus at Thebes, she should there, in the place to which she had come, have a memory of him; and after this, when she got understanding of the Hellenic tongue, she established an Oracle, and she reported, I suppose, that her sister had been sold in Libya by the same Phoenicians by whom she herself had been sold. Moreover, I think that the women were called doves by the people of Dodona for the reason that they were barbarians and because it seemed to them that they uttered voice like birds; but after a time (they say) the dove spoke with human voice, that is when the woman began to speak so that they could understand; but so long as she spoke a Barbarian tongue she seemed to them to be uttering voice like a bird: for if it had been really a dove, how could it speak with human voice? And in saying that the dove was black, they indicate that the woman was Egyptian. The ways of delivering oracles too at Thebes in Egypt and at Dodona closely resemble each other, as it happens, and also the method of divination by victims has come from Egypt.

Floating Oracle of Leto

Fifth Century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: The Oracle which is in Egypt is sacred to Leto, and it is established in a great city near that mouth of the Nile which is called Sebennytic, as one sails up the river from the sea; and the name of this city where the Oracle is found is Buto, as I have said before in mentioning it. In this Buto there is a temple of Apollo and Artemis; and the temple-house of Leto, in which the Oracle is, is both great in itself and has a gateway of the height of ten fathoms: but that which caused me most to marvel of the things to be seen there, I will now tell. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A.D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

There is in this sacred enclosure a house of Leto made of one single stone upon the top, the cornice measuring four cubits. This house then of all the things that were to be seen by me in that temple is the most marvellous, and among those which come next is the island called Chemmis. This is situated in a deep and broad lake by the side of the temple at Buto, and it is said by the Egyptians that this island is a floating island. I myself did not see it either floating about or moved from its place, and I feel surprise at hearing of it, wondering if it be indeed a floating island. In this island of which I speak there is a great temple-house of Apollo, and three several altars are set up within, and there are planted in the island many palm-trees and other trees, both bearing fruit and not bearing fruit.

And the Egyptians, when they say that it is floating, add this story, namely that in this island which formerly was not floating, Leto, being one of the eight gods who came into existence first, and dwelling in the city of Buto where she has this Oracle, received Apollo from Isis as a charge and preserved him, concealing him in the island which is said now to be a floating island, at that time when Typhon came after him seeking everywhere and desiring to find the son of Osiris. Now they say that Apollo and Artemis are children of Dionysos and of Isis, and that Leto became their nurse and preserver; and in the Egyptian tongue Apollo is Oros, Demeter is Isis, and Artemis is Bubastis. From this story and from no other AEschylus the son of Euphorion took this which I shall say, wherein he differs from all the preceding poets; he represented namely that Artemis was the daughter of Demeter. For this reason then, they say, it became a floating island.

Oracles in Ancient Egyptian Law Courts

Oracles were introduced to Egyptian law courts in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.) Sandra Lippert of Universität Tübingen wrote: “Oracle proceedings used the same system as other oracles: the answer of the god was derived from the movements his cult statue made during a festive procession. A forward motion, called hnn, “nodding,” was considered as affirmative answer, a backward motion, called naj n HA=f, “receding,” as negative. Oracular proceedings are best attested from Deir el-Medina. [Source: Sandra Lippert, Universität Tübingen, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

African head amulet

“The procedure for oracular trials resembled normal procedure inasmuch as the plaintiff gave his statement, sometimes probably in writing, including the presentation of documents. Oracles were approached for mainly the same types of suits as local courts. But the presence of the defendant seems not to have been necessary, especially since oracular procedures were quite common in cases of theft when the culprit was unknown. Three basic methods to address the god can be distinguished: 1. oral yes/no questions like “Is A’s claim correct?” or “Is B the culprit?” which the god answered with “yes” or “no” movements; 2. orally presented lists of possibilities (e.g., of possible thieves or prices for disputed goods) during the reading of which the god gave his assent at a certain point; 3. double written statements (positive and negative versions of a statement or the statements of plaintiff and defendant) between which the god chose, possibly by moving towards one of them. Like normal court sessions, oracle sessions were recorded.

“In the transcripts, the participants and onlookers were put down as witnesses for the judgment. The movement was usually translated directly into the standard judgment formula (see above), e.g., “X is right, Y is wrong.” The condemned was able to appeal at another god’s oracle. It remains unclear whether oracular trials took place on days when there were religious processions anyway or whether special processions had to be arranged for them: the fact that in Deir el-Medina most oracle trials are dated to the 10th, 20th, and 30th day of the month when the workers had their day off cuts both ways. During the 21st and 22nd Dynasties, when Amun became nominally head of the Upper Egyptian state, oracles also took over the notarial functions of courts, i.e., the authentication of documents.”

“The evidence for oracular proceedings in the Late Period is sparse and indirect. A lavishly illustrated transcript of an oracular proceeding of the 26th Dynasty with an exceptionally large number of witness copies concerns the transfer of a priest from one priesthood to another and is therefore more administrative than judicial in nature. Herodotos II, 174 reports that king Amasis of the 26th Dynasty had repeatedly been acquitted from quite legitimate accusations of theft in his youth by the oracles of some gods but condemned by others, with the effect that, as king, he esteemed only the latter and did not take the first seriously any more. There is no evidence for real oracular proceedings after the 26th Dynasty—what Seidl supposes to be writs in an oracular trial are letters to gods containing prayers for protection against injustice. Although oracle questions with legal content, usually concerning cases of fraud or theft with unknown perpetrator, are still to be found in the Roman Period and, in Christianized form, continue into the seventh century CE, these are no longer part of a proper trial.”

Curses in Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians, Mesopotamians, Greeks, Romans, Persians, Jews, Christians, Gauls and Britons all dispensed curse tablets to placate "unquiet" graves and call up the spirits of the underworld to make trouble. One Egyptian curse outside a tomb read: "Listen to you! The priest of Hathor will beat twice any one of you who enters this tomb or does harm to it. The gods will confront him because I am honored by his Lord. The gods will not allow anyone bad to enter my tomb, [the] crocodile, [the] hippopotamus, and the lion will eat him. A curse found in a tomb near the pyramids read: “As for any person, male or female, who shall do evil against this tomb and shall enter therein, the crocodile shall be against him upon water, the hippopotamus shall be again him in the water, and scorpion shall be against him on the land.”

Dr Geraldine Pinch of Oxford University wrote for the BBC: “Though magic was mainly used to protect or heal, the Egyptian state also practised destructive magic. The names of foreign enemies and Egyptian traitors were inscribed on clay pots, tablets, or figurines of bound prisoners. These objects were then burned, broken, or buried in cemeteries in the belief that this would weaken or destroy the enemy. [Source: Dr Geraldine Pinch, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“In major temples, priests and priestesses performed a ceremony to curse enemies of the divine order, such as the chaos serpent Apophis-who was eternally at war with the creator sun god. Images of Apophis were drawn on papyrus or modelled in wax, and these images were spat on, trampled, stabbed and burned. Anything that remained was dissolved in buckets of urine. The fiercest gods and goddesses of the Egyptian pantheon were summoned to fight with, and destroy, every part of Apophis, including his soul (ba) and his heka. Human enemies of the kings of Egypt could also be cursed during this ceremony. |::|

“This kind of magic was turned against King Ramesses III by a group of priests, courtiers and harem ladies. These conspirators got hold of a book of destructive magic from the royal library, and used it to make potions, written spells and wax figurines with which to harm the king and his bodyguards. Magical figurines were thought to be more effective if they incorporated something from the intended victim, such as hair, nail-clippings or bodily fluids. The treacherous harem ladies would have been able to obtain such substances but the plot seems to have failed. The conspirators were tried for sorcery and condemned to death. [Source: Dr Geraldine Pinch, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Curses were largely confined to temple rituals performed to combat malevolent forces and enemies of the state. Recited in the form of 'execration texts', priests often inscribed the names of those to be cursed on pots, which were then smashed to destroy the enemies' power. Alternatively, figurines made from wood, clay or wax were then smashed, burnt, pierced or bound to gain power over those invoked, their names and various spells again added to make them more effective.

“Such figurines were also used on a more personal level by those wishing to gain control over specific individuals. The courtiers put on trial for the attempted assassination of King Ramses III (c.1184-1153 B.C.) were accused of making wax figurines of the palace guards in an attempt to overwhelm them, and the curse figurine which appears in our story is based on a rare wooden example dating from c.2000 B.C.; with its arms tied behind its back to render the intended victim harmless, its hastily scribbled inscription simply states 'Die Henwy, son of Intef!' |::|

Book: “Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World” by John Gager, professor or religion at Princeton (Oxford University Press, 1998)

Funerary Curses in Ancient Egypt

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: While extremely rare, some Old Kingdom-era tombs do promise vengeance against those who disturb them. The tomb of the 10th-9th century B.C. ruler Khentika Ikhekhi contains an inscription on the wall that reads, "As for all men who shall enter this my tomb... impure... there will be judgment... an end shall be made for him... I shall seize his neck like a bird... I shall cast the fear of myself into him." [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast. January 15, 2017]

In his book Valley of the Golden Mummies, archeaologist Zahi Hawass says that the tombs of the builders of the Great Pyramid of Giza included the warning “All people who enter this tomb who will make evil against this tomb and destroy it may the crocodile be against them in water, and snakes against them on land. May the hippopotamus be against them in water, the scorpion against them on land." Hawass declined to disturb those remains, but later participated in the excavation of the mummified remains of two children in Bahariya Oasis, and reported being haunted by the children in his dreams.

Dr Joann Fletcher of the University of York wrote for BBC: “Although the ancient Egyptians did occasionally use such 'curses' in their tombs, the relatively few examples which have been found are fairly understated. More concerned with making sure anyone entering the tomb is sufficiently pure, the deceased place their trust in the gods to see that justice is done if their tomb is harmed. A rare example from a royal tomb is to be found in the Old Kingdom Pyramid Texts, which warn that 'anyone who dare lay a finger on this pyramid and on this temple which belong to me and my ka (soul) will face the judgement of the gods and will cease to exist!'. Perhaps the most graphic warning occurs in the Sakkara tomb of Ankhmahor, with the tomb owner stating that 'As for that which anyone might do against this my tomb, the same will be done to his property. I am an excellent priest, knowledgeable in secret spells and all forms of magic, and as for anyone who enters my tomb impure or who do not purify themselves, I shall seize him like a goose and fill him with fear at seeing ghosts upon the earth.... But as to those who enter my tomb pure and peaceful, I shall be his protector in the court of the Great God', a reference to Osiris, Lord of the Underworld, who was the ultimate judge of dead souls. [Source: Dr Joann Fletcher, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Moss wrote: Tomb raider curses are not exclusively associated with ancient Egyptian mythology and pyramids. A number of fourth- and fifth-century CE Coptic Christian martyrdom stories included appendices that warn against the destruction of those who seek to steal the remains of the martyr. These curses were directed against other Christians who, for religious reasons, wanted to acquire the holy relics of the saints for themselves.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024