Home | Category: Religion and Gods

RITUALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

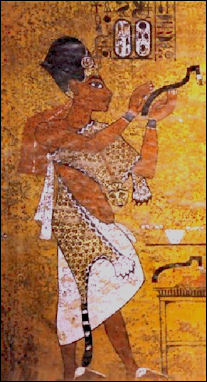

Opening of the Mouth

of Tutankhamun and Aja Ancient Egyptian gods required a lot of attention. “The Book of the Dead” and wall inscriptions are full of details about rites and rituals for specific gods.

Before kings or priests entered a shrine they had to purify themselves in a sacred pool. After entering the sanctuary they said liturgy while they lighted charcoal and incense in a censer next to the statue, made some offerings, anointed the statue, redressed it in new clothes with a proper insignia and performed rituals which allowed the statue to speak and breath. During the libation rituals an alabaster sistrum — a ritual noisemaker topped with cobras and the falcon-god Horus — was used to ward off violence. Feasts were held before statues were as placed back in their shrines.

In a temple in Hierakonpolis dated to 3500 B.C. large dangerous animals such as crocodiles and hippopotami were sacrificed perhaps as symbols of natural chaos. Bulls were sacrificed by the ancient Greeks, Romans and Druids but treated with reverence by Egyptians (black bulls in particular were given harems and palaces because they were believed to be related to the bull-god Apis).

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TEMPLE WORKERS, WEALTH AND PROPERTY africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PRIESTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SACRIFICES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: PIGS, BULLS AND POSSIBLY HUMANS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PERSONAL RELIGION IN ANCIENT EGYPT: VOTIVE OFFERINGS AND DOMESTIC RELIGIOUS PRACTICES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CULTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ASTROLOGY, SUPERSTITIONS, CURSES AND AMULETS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

MAGIC IN ANCIENT EGYPT: SPELLS, WANDS AND DREAMS africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Temple Ritual: Performance, Patterns, and Practice” by Katherine Eaton (2013) Amazon.com;

“Wine & Wine Offering In The Religion Of Ancient Egypt” by Mu-chou Poo (2013) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths,and Personal Practice” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

“Gods Priests & Men” by Alan Lloyd Amazon.com;

“The Priests of Ancient Egypt” by Serge Sauneron, David Lorton, Jean-Pierre Corteggiani (2000) Autho Amazon.com;

“The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2000) Amazon.com;

“Temple of the Cosmos: The Ancient Egyptian Experience of the Sacred” by Jeremy Naydler (1996) Amazon.com;

“Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Geraldine Pinch, a professor of Egyptology at Cambridge University (1994) Amazon.com;

“Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Sacred Magic of Ancient Egypt: The Spiritual Practice Restored”

by Rosemary Clark (2021) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Religion an Interpretation” by Henri Frankfort (1948, 2011) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Gods Speak: A Guide to Egyptian Religion” by Donald B. Redford (2002) Amazon.com;

Daily Rituals Performed by Priests at Ancient Egyptian Temples

Everyday priests took care of the statues of the gods as if they were living people. In a daily ritual called the “opening of the mouth,” priests gave the statue offerings of food in the morning and evening, clothed them in clean linen and new jewelry and had new make-up applied. These rituals were performed in sanctuaries — in which only priests and pharaohs were allowed — within the temples. Ordinary people had no idea what went on in these sanctuaries. Sometimes the same rituals were performed on mummies.

The daily acts of worship performed by priests are known from several contemporary sources to have been essentially the same in the case of the various gods. Whether it were Amun or Isis, Ptah or the deceased to whom divine honours were to be paid,'' we always find that fresh rouge and fresh robes were placed upon the divine statue, and that the sacred chapel in which it was kept was cleansed and filled with perfume. The god was regarded as a human being, whose dwelling had to be cleansed, and who was assisted at his toilet by his servants. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

These ceremonies doubtless differed both in detail and extent at the various sanctuaries; e.g. the priest at Thebes had about sixty ceremonies to perform, whilst at Abydos thirty-six were found to be sufficient. The form and object of the worship however were always the same, though the details might vary. As a general rule also, the priest had to recite an appointed formula at each separate ceremony.

At Abydos,' the priest first offered incense in tlic hypostyle hall, saying : " I come into thy presence, O great one, after I have purifiedmyself. As I passed by the goddess Tefnut, she purified me ... I am a prophet, and the son of a prophet of this temple. I am a prophet, and I come to do what ought to be done, but I do not come to do what ought not to be done." . . . He then stepped in front of the shrine of the god and opened the seal of clay with these words : " The clay is broken and the seal loosed that this door may be opened, and all that is evil in me I throw (thus) on the ground."

When the door was open, he first incensed the sacred uraeus snake, the guardian of the god, greeting it by all its names; he then entered the Holy of Holies, saying : " Let thy seat be adorned and thy robes exalted; the princes of the goddess of heaven come to thee, they descend from heaven and from the horizon that they may hear praise before thee. . . . He next approached the " great seat," i.e. that part of the shrine where the statue of the god stood, and said : " Peace to the god, peace to the god, the living soul, conquering his enemies. Thy soul is with me, thine image is near me; the king brought to thee thy statue, which lives upon the presentation of the royal offerings. I am pure." The toilet of the god then commenced — " he laid his hands on him," he took off the old rouge and his former clothes, all of course with the necessary formulae. He then dressed the god in the robe called the Nems, saying : " Come white dress ! come white dress ! come white eye of Horus, which proceeds from the town of Nechebt. The gods dress themselves with thee in thy name Dress, and the gods adorn themselves with thee in thy name Adornvientr

The priest then dressed the god in the great dress, rouged him, and presented him with his insignia : the sceptre, the staff of ruler, and the whip, the bracelets and anklets, as well as the two feathers which he wore on his head, because " he has triumphed over his enemies, and is more splendid than gods or spirits." The god required further a collarette and an amulet, two red, two green, and two white bands; when these had been presented to him the priest might then leave the chapel. Whilst he closed the door, he said four times these words : " Come Thoth, thou who hast freed the eye of Horus from his enemies — let no evil man or evil woman enter this temple. Ptah closes the door and Thoth makes it fast, closed and fastened with the bolt." So much for the ceremonies regarding the dress of the god; the directions were just as precise concerning the purification and incensing of the room, and the conduct of the priest when he opened the shrine and " saw the god." According to the Theban rite, for instance, as soon as he saw the image of the god he had to " kiss the ground, throw himself on his face, throw himself entirely on his face, kiss the ground with his face turned downwards, offer incense," and then greet the god with a short psalm.

Maru Aten, a Ritual Complex at Amarna

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “The Maru Aten was a ritual complex, incorporating a Sunshade of Ra dedicated to Meritaten, at the far south end of the Amarna plain. The site is known for having been elaborately decorated, including with painted pavements, but is now lost under cultivation. The site comprised two enclosures, a northern one, built first, and southern one. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The northern court was dominated by a large shallow pond surrounded by trees and garden plots, with a viewing platform and causeway built at one end. At the other end was a stone shrine adjacent to an artificial island on which was a probable solar altar flanked perhaps by two courts. The northern enclosure also contained T-shaped basins, probable houses, and other buildings of uncertain purpose. The southern enclosure likew ise had a probable central pool (not excavated) and a building at either end, one a mud-brick ceremonial structure, perhaps for use by the royal family, and the other a stone building of uncertain function.

“The “Lepsius Building” and El-Mangara A few hun dred meters southwest of the Maru Aten there likely stood another stone-built cult or ceremonial complex, noted briefly by Lepsius in 1843, while at the site of el-Mangara, about 1700 meters southeast of Kom el-Nana, evidence was also collected in the 1960s for a stone-built complex, in the form of largely intact decorated blocks, mud-brick, and Amarna Period sherds. Both sites are now lost under cultivation.”

Execration Rituals in Ancient Egypt

sacrificial table

Execration rituals were conducted throughout the history of ancient Egypt. They were intended to prevent rebellious actions by Egyptians, foreigners, or supernatural forces by textually and kinetically destroying enemies via inanimate, animal or human substitutes. Kerry Muhlestein of Brigham Young University wrote: “Execration rituals were stylized magical actions aimed at thwarting or eradicating foes and were similar in nature to other protective measures, such as apotropaic animal sacrifice or walking on depictions of enemies. Execration rites took place from at least early in the Old Kingdom through the Roman Period. Over 1,000 execration deposits have been found, mostly in cemeteries, notably at Semna, Uronarti, Mirgissa, Elephantine, Thebes, Balat, Abydos, Helwan, Saqqara, and Giza. Main sources for understanding the rite are the surviving manuscripts of its various versions, plus texts that were often inscribed on the ritual objects and thus became a physical component of the ritual. Important texts include Papyrus Bremner-Rhind, P. Louvre 3129, P. British Museum 10252 , and P. Salt 825. Execration texts could be as simple as lists of forces and people against whom the rite was enacted, or could contain substantial formulae. Variations on the concept behind the rite eventually spawned both love charms and spells for warding off bad dreams. [Source: Kerry Muhlestein, Brigham Young University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“The earliest traceable manifestations of aspects of the rite are motifs of bound prisoners (part of Egypt’s earliest iconography) and actions connected to offerings and purification rituals. As to the latter, Assmann suggests that after red pots were used for offerings they had to be destroyed and that the smashing of these pots was assigned an overlapping meaning of scaring away—or eventually destroying—enemies (cf. Pyramid Texts 23 and 244). Purification rites also involved the use of red pots. In the Pyramid Texts, warding off enemies often precedes and/or succeeds both offering and purification pericopes. PT 214, for example, illustrates the need for warding off the inimical during purification. This connection continued throughout Pharaonic history and is perhaps best reflected in the Festival of the Kites (the birds that symbolized the goddesses Isis and Nephthys), which purified and placed protection around the temple, and during which Seth was driven to the executioner and a “great rite of protection” was performed. The text repeatedly notes that those who know creation can also eliminate their own enemies, thus tying the re-creative aspect of purification to execration. While the use of (predominantly red) pots continued in funerary offerings for millennia, by the Old Kingdom the ritual of smashing pots had given birth to independent execration rites. By the Middle Kingdom execration texts had become standardized (though they would change over time), perhaps indicating that the rite had also taken a standard form. Some execration rites arose due to specific circumstances, but at least by the Late Period (712–332 B.C.) there were also both daily and cyclical festival execrations.

“Execration rites could be aimed at political, preternatural, or personal enemies. The political and preternatural were often tied together. The Book of Felling Apophis, for example, instructs that the rite will fell the enemies of Ra, Horus, and Pharaoh. Political rituals likely began as attempts to deal with rebellious Egyptians, but soon included rebellious vassals and foreign enemies, and were almost always directed toward potential problems as a type of proactive apotropaic measure. The victims of these rites were those who, whether dead or alive, would in the future rebel, conspire rebellion, or think of speaking, sleeping, or dreaming rebelliously, or with ill- intent. These vague enemies, as well as specific individuals, groups, or geographic locations, were named for things they might do in the future, though some individuals presumably were included because of things they had already done. The standardization of the texts, the concern with foreign entities, and the desire to protect the state, ruler, and divine, combined with the knowledge of foreign politics, geography, and leaders that the texts demonstrate, all indicate that these were state- sponsored rites.

“The figures and pots used in the rites were often inscribed with the rebellion formula, but sometimes only with personal names (not necessarily foreign), and were frequently not inscribed at all. Simple rites associated with private graves, and those exhibiting only personal names or no text, indicate an individual use of execration rituals, as well. Private, small-scale rituals are far less archaeologically visible, especially when they involved the use of cheaper, less durable substances. Versions of execration were carried out both on a large-scale basis by the state and on a small scale by individuals throughout Egyptian history.

“While red pots were the earliest objects utilized in the rites, and remained a common article of manipulation, by the late Old Kingdom, papyrus, hairballs, figurines, statues, and statuettes made of clay, stone, wax, or wood were also used. Live animals also likely composed a component of the ritual. If the Bremner-Rhind Papyrus is any indication, wax figures and a fresh sheet of papyrus, on which the targeted name was written, were among the most commonly used materials. The animals, hair, papyrus, wood, and wax ritual victims are largely archaeologically invisible, making the known (mostly clay) remains of the ritual a vast under-representation of the frequency of the rite. At the most complete execration find—the Middle Kingdom fortress at Mirgissa—besides the remnants of melted wax, other trace remains indicate the use of nearly 200 broken inscribed red vases, over 400 broken uninscribed red vases, nearly 350 mud figurines, four limestone figures, and one human, whose head was ritually severed and buried upside down as part of the rite. Similar evidence of human victims as execration figures also appears in an early 18th-Dynasty context at Avaris.

“Within a full execration, each ritual action could require a separate rite, and though not every execration included all of the following components, some did: ritual objects could be bound, smashed (red pots, probably with a pestle), stomped on, stabbed, cut, speared, spat on, locked in a box, burned, and saturated in urine, before (almost always) being buried (sometimes upside down). As an example, a portion of one rite calls for the object to be bound and gives subsequent instructions to “spit on him four times . . . trample on him with the left foot . . . smite him with a spear . . . slaughter him with a knife . . . place him on the fire . . . spit on him in the fire many times”. A full rite could employ any of these actions numerous times with numerous figures. Thus various magical measures were taken to prevent chaotic forces from acting before they could even begin”.”

Temple Offerings in Ancient Egypt

bronze model of an offering table

Not only had the priest to dress and serve his god, but he had also to feed him; food and drink had to be placed daily on the table of offerings, and on festival days extra gifts were due. In other countries these offerings have been generally maintained by the gifts of pious individuals, and in Egypt also this was probably originally the case; but, as we have said before, under the New lunpire especially the state stepped into the place of the people, and if private individuals brought offerings, these were quite insignificant in comparison with the great endowments made by the kings. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

We have much information as to the extent and the kinds of offerings; on the outer wall of the great temple of Medinct Habu there still exist parts of a list of the offerings instituted by Ramses II. and Ramses III. for this sanctuarv, which was erected by them. These may have been richer than those of earlier temples, though they would certainly not equal those of Karnak and Luxor. If we leave on one side the less important items, such as honey, flowers, incense, etc, and consider simply the various meats, drinks, and loaves of bread placed on the tables of offerings, we shall find as follows: every day of the year the temple received about 3220 loaves of bread, 24 cakes, 144 jugs of beer, 32 geese, and several jars of wine. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

In addition to this revenue, which was doubtless chiefly used for the maintenance of the priests and the temple servants, special endowments were established for special days. There were extra offerings for the eight festivals which recurred every month. On the second, fourth, tenth, fifteenth, twenty-ninth, and thirtieth days of each month, 83 loaves, 15 jugs of beer, 6 birds, and I jar of wine were brought into the temple; while on the new moon and on the sixth day of the month the offerings amounted to 356 loaves, 14 cakes, 34 jugs of beer, one ox, 16 birds, 23 jars of wine." Still more important were the offerings on great festival days, of which there was no lack in the ecclesiastical year of ancient Egypt. Thus, for instance, a feast of ten days was solemnised in the last decade of the month Koiak to the Memphite god Ptah-Sokar-Osiris; the temple of Medinet Habu took part in this festival. If we again pass over the unessential items, the following list of offerings shows us the royal endowment for these festival days :

One question forces itself involuntarily upon the reader, what became of all this extra food after it had fulfilled its purpose of lying on the altar before the god ? We might think that it would be brought into the provision-house and used gradually for the maintenance of the temple .servants and priests; the various amounts of the offerings would then merely prove the greater or less importance of the feast. On the different festival days the number of loaves of bread varies from 50 to 3694, and the jugs of beer from 15 to 905, the birds from 4 to 206, the different degree of sanctity between the individual days could not account for so much variation.

The 26th of Koiak, the feast of Sokar, was evidently the principal day of the whole festival, but it could not be twenty times more holy than the 30th of Koiak, the sacred day, when the pillar of Ded was erected. It is much more likely that there was a more practical reason for the choice of these numbers : the food probably supplied different numbers of persons, and these persons were not divine images, but the priests and the laity who took part in the festival. The number of the latter probably varied much on the different festival days; according as the festival was a closed or an open one, the crowd at the feast to consume the offerings would vary in proportion. This would also explain the difference in the quality of the food; at one time the people assisting would belong to the upper classes, and would require roast meat and cake; at another time the lower classes preponderated, and for them loaves of bread would suffice.

Meaning of Temple Offerings in Ancient Egypt

Mu-Chou Poo of the Chinese University of Hong Kong wrote: “The ritual offerings in Egyptian temples and funerary settings constitute an important part of the outward expressions of Egyptian piety. In temple rituals in particular, according to the images preserved on temple walls, we know that often, though not always, each ritual act was accompanied by a series of incantations (often inscribed on the wall beside the images), including the title of the ritual, the ritual liturgy, and the reply of the deity who was receiving the ritual performance or offering. [Source: Mu-Chou Poo, Chinese University of Hong Kong, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

"Although there is still some uncertainty regarding whether the temple reliefs represent actual ritual acts, most scholars agree that the meaning of the rituals can be deciphered, at least partially, by examining these texts. Although these ritual liturgies had a long-standing textual tradition that can be traced as far back as the Pyramid Texts, most of the best-preserved texts were from the Ptolemaic and Roman temples. The present discussion, therefore, mostly utilizes texts from this period.

“The basic meaning of any offering was to incur the blessing of the deities, or deceased ancestors, who were regarded as capable of protecting or aiding those who presented the offering. In funerary settings, as we saw in the offering lists, the Egyptians would provide what they considered an appropriate amount and selection of offering items. The significance of the offerings as sustenance for the deceased is self-evident. However, in the temple-ritual setting, although the primary significance of offerings to deities remained basically the same as that of funerary offerings, the subsequent elaboration of the rituals and liturgies that accompanied the offerings to deities served to exalt the meanings attached to the actual offering items. Thus the offering of a certain item would become a symbolic action relevant to either the characteristics or functions of the recipient deities, or the offering item itself would become symbolic of a certain beneficent deed or cosmic force—on a level of importance matched by that of the deities.

“Only occasionally do we find an item that is offered exclusively to a certain deity, the offering of mirrors to Hathor being an example. In most cases, however, there seems to be no one-to-one correspondence between the offering and the recipient god. This indicates that despite particular theological or mythological allusions implied by such offerings as wine or water, the basic underlying significance of an offering as an object that supplies a “need” of the deity in exchange for blessings remains the same.”

Liquids in Ancient Egyptian Temple Rituals

two priests, one holding a vase for libations

Mu-Chou Poo of the Chinese University of Hong Kong wrote: “In ancient Egypt the liquids most commonly used in temple rituals included wine, beer, milk, and water. The meaning of the rituals were intimately tied to the qualities of the liquid used as well as to the religious and mythological associations the liquids were known to possess. With the exception of beer, all the ritual offerings of liquids were connected in some way with the idea of rejuvenation. [Source: Mu-Chou Poo, Chinese University of Hong Kong, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Of the numerous rituals recorded on temple walls, the offering of liquids occupied a rather large proportion. Here we discuss four kinds of liquids employed in temple rituals: wine, beer, milk, and water. The meaning of an individual ritual act was intimately related to the nature of the liquid employed, as well as to whatever religious and mythological associations the liquid was known to have. Certain deities might have some particular connections with a particular offering, as we shall see below. Yet as far as we can tell, there could be multiple recipients for the same kind of offering, and a particular deity could receive multiple offerings at different times.

“In the Temple of Hathor at Dendara, on the outer wall of the sanctuary, the offering of wine was represented symmetrically opposite representations of beer offerings on the opposing walls, indicating a certain affinity between them, perhaps due to their alcoholic content. The offering of water, on the other hand, was paired with the offering of bread and beer, which suggests that water, bread, and beer were endowed with the power of sustenance. Moreover, the offering of wine was also in one instance paired with the “dance for Hathor,” which implicitly suggests a connection between wine and the “ecstasy of Hathor” .

“It is interesting that all the ritual offerings of liquids were, each in its own way, somehow connected with the idea of rejuvenation. Perhaps this need not be surprising, since all the offering-liquids were, in a sense, nutrients that could be used by the human (or divine) body, and could thus be considered sources of rejuvenation. In the case of beer, the absence of specific allusions to the intoxicating power of alcohol and the mythological stories of Hathor-Sakhmet or Hathor-Tefnut in the offering liturgies remains unexplained.”

Wine in Ancient Egyptian Temple Rituals

Mu-Chou Poo of the Chinese University of Hong Kong wrote: “Wine was often an important item in funerary and temple cults. From as early as the Old Kingdom, wine was regularly mentioned in offering lists as part of the funerary establishment . In temple rituals, wine was also often offered to various deities. In the pyramid temple of Fifth Dynasty king [Source: Mu-Chou Poo, Chinese University of Hong Kong, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

glass and bronze grapes

Sahura, for example, the king was shown offering wine to the goddess Sakhmet. Besides its general significance as an item that pleased the deities, the offering of wine took on certain specific religious and mythological associations. Already in the Pyramid Texts, Osiris was mentioned as the “Lord of Wine in the Wag Festival”. The Wag Festival was celebrated at the beginning of the inundation, on the 17th, 18th, or 19th of Thoth, the first month of inundation . The festival itself was a funerary feast that was probably aimed at the celebration of the resurrection of life that the inundation brought.

Since Osiris epitomized resurrection, there may be a certain connection between Osiris as the god of vegetation and rejuvenation and the symbolic coming to life of the grapevine. The fact that wine production depended upon the coming of the inundation might therefore have fostered the meaning of wine as a symbol of life and rejuvenation. A text in the Ptolemaic temple of Edfu contains the following sentence: “The vineyard flourishes in Edfu, the inundation rejoices at what is in it. It bears fruit with more grapes than [the sand of] the riverbanks. They [the grapes] are made into wine for your storage . . . .”. Thus the relationship between the inundation and the production of wine is clearly stated.

“On the day following the Wag Festival, there was, at least in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, a festival of “the Drunkenness of Hathor” celebrated at Dendara. The calendar of festivals at Edfu alludes to the relationship between Hathor and the inundation: “It is her [Hathor’s] father, Ra, who created it for her when she came from Nubia, so that the inundation is given to Egypt” .

“In the Ptolemaic and Roman temples, Hathor-Sakhmet was often referred to as “Lady of Drunkenness,” and this epithet was often regarded as an allusion to the famous story “The Destruction of Mankind”... Although beer was featured in the story, the effect of alcoholic drink in general was probably what made wine (and beer) an important temple offering, particularly in connection with the honoring of the goddess Hathor-Sakhmet.

“In another mythological story about Hathor- Tefnut, or the Eye of Ra, the god Ra commanded that his daughter, the lioness Hathor-Tefnut, be brought back to Egypt from Nubia. Parallel to the story of the Destruction of Mankind, Thoth and Shu were assigned the mission. After Hathor was brought back to Egypt, her wild and bloodthirsty nature needed to be appeased with dance and music, and the offering of wine. As Greek and Roman authors noted, the Nile water turned red during the inundation, which suggests the color of wine. As Hathor’s return to Egypt (according to the mythological story) corresponded to the rise of the Nile waters—which not only resembled wine in color, but could in fact bring a prosperous harvest of grapes and wine—it is fitting that she be referred to as the Mistress of Drunkenness and identified with the inundation.

“On the other hand, when we examine the numerous offering scenes on the temple walls, it becomes clear that, as a common offering, wine could be offered to many deities other than Hathor. The religious meaning of wine, moreover, was not limited to the allusions to the mythological stories related to Hathor, or to its intoxicating nature, important as it was in many ancient cultures, but had wider significance. The color of wine, when it was red, and even disregarding its association with the mythological story, already suggested an association with blood and the life-giving force of nature. As this association was not limited to ancient Egyptian culture, it is all the more possible to believe that the symbolic association of wine and blood did exist in Egypt. The winepress god, Shesmu, for example, was referred to as bringing wine to Osiris on the one hand—“Shesmu comes to you [Osiris] bearing wine”: shown pressing the blood of the enemies with the winepress. It is reasonable to suspect here an allusion to the grape juice being pressed from the winepress.

“Moreover, offering liturgies testify that wine was regarded metaphorically as the “Green Eye of Horus”—that is, the power of rejuvenation: “Take to yourself wine—the Green Horus Eye. May your ka be filled with what is created for you...”. And reference to the contending of Horus and Seth can also be found in the liturgy of wine-offering: “Take to yourself the wine that was produced in Kharga, O noble Falcon. Your wedjat-eye is sound and supplied with provision; secure it for yourself from Seth. May you be powerful by means of it . . . may you be divine by means of it more than any god.”“

Beer in Ancient Egyptian Temple Rituals

Mu-Chou Poo of the Chinese University of Hong Kong wrote: “Being the most popular and affordable drink in ancient Egypt, beer featured prominently as an offering in funerary as well as temple rituals. The brewing of beer involves the fermentation of cereals, and, as studies of beer residues show, the brewing of beer in general comprises several steps. First, a batch of grain was allowed to sprout, thereby producing an enzyme. Then another batch of grain was cooked in water to disperse the starch naturally contained within it. The two batches were subsequently combined, causing sugar to be produced, and then sieved. Finally, the sugar-rich liquid was mixed with yeast, which fermented the sugar into alcohol. [Source: Mu-Chou Poo, Chinese University of Hong Kong, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Like the offering of wine, the beer-offering was a common ritual in Egyptian temples. However, although Hathor’s epithet “Mistress of Drunkenness” was found in beer-offering scenes , it is somewhat surprising to learn that, contrary to our expectations, the mythological story of the Destruction of Mankind does not appear to have been alluded to in the beer-offering liturgies. What were emphasized in the offering liturgies were concerns regarding the correctness and meticulousness with which the beer was brewed: “Take the sweet beer, the supply for your majesty, which is brewed correctly. How sweet is its taste, how sweet is its smell!. How beautiful are these beer jars, which are brewed at the correct time, which fill your ka at the time of your wish. May your heart be joyful daily. Take for yourself the wonderful beer, which the noble one has brewed with her hands, with the beautiful plant from Geb and myrrh from Nepy.”

“The deities’ emphasis on the proper brewing of beer is interesting, since the production of wine was never mentioned as having been done by gods. It is mentioned that music was performed during the offering of beer: “Take the beer to appease your heart...for your ka according to your desire, may you drink it, may [you] be happy, as I make music before you”. This leads us to rethink whether the epithet of Hathor as “Mistress of Drunkenness” necessarily alludes to the mythological story of the Destruction of Mankind, and not to a more general sense of intoxication and rejuvenation. After all, beer, above all other offerings, would be the obvious choice for alluding to the story if indeed the story gave rise to Hathor’s epithet.”

Milk in Ancient Egyptian Temple Rituals

heavenly cow

Mu-Chou Poo of the Chinese University of Hong Kong wrote: “Since the function of milk is to nourish, and its white color is associated with purity, the significance of the offering of milk in temple rituals was also built around these allusions. Milk was often offered, for example, to Harpocrates (the child Horus), milk being a obvious source of nourishment for children: “May you be filled with milk from the breasts of the hesat-cow” ; “Take the milk, which is from the breast of your mother”. The result of nourishment was no doubt to strengthen the body, as the following texts indicate: “May your limbs live by means of the milk and your bones be healthy by means of the white Horus Eye [milk]....The king rejuvenates his [Osiris’s] body with what his heart desires [milk]”.

“Milk was also offered to other deities, among them Hathor and Osiris, in various rituals , especially in the Abaton-ritual, in which 365 bowls of milk were brought before Osiris daily . One offering liturgy reads: “Oh, ‘White [milk]’, which is from the breasts of Hathor. Oh, sweet [milk], which is from the breasts of the mother of Min; it entered the body of Osiris, the great god and lord of Abaton”. Here the whiteness of milk is clearly referenced, thus indicating milk as a liquid of purification. This is confirmed by such liturgical texts as “offering milk to his father and purifying [lit. overflowing] the offering of his ka,” or “purifying the offering of His Majesty with this White Eye of Horus [milk]”. Since the libation of water was metaphorically referred to as the “milk of Isis”, the reverse is also true. These general religious significations aside, there seem to be no further mythological or theological allusions that can be connected to milk.”

Water in Ancient Egyptian Temple Rituals

Mu-Chou Poo of the Chinese University of Hong Kong wrote: “Of all the temple rituals, the ritual of purification was likely the one that needed to be performed first in any program of daily ritual. The priest, the temple grounds, and even the libation jars needed to be purified before any ritual offerings to the deities were performed. The water of purification could be presented to the deities in two ways, either poured onto the ground or onto the altar or statue as a gesture of general purification: “Spell for purifying [ ] as far as the heaven, the earth, to Harakhty, to the great Ennead, to the small Ennead, to Upper Egypt, and to Lower Egypt. My arms are given the water [lit. inundation], that it may purify the offering and every good thing of Tebtunis, with its Ennead, [ ] for your ka [?]. It is pure. Purification with the four jars of water: take the Eye of Horus, as it purifies your body. Oh water, may you purge all impurity and evil from the daughter of the Creator, oh Nun, may you purify her face.” Thus the water cleansed the statue of the deity from the outside, as an ablution, purifying the image in a direct and mundane sense. [Source: Mu-Chou Poo, Chinese University of Hong Kong, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“On the other hand, water could be offered to the deities as a drink (libation). In a papyrus found in the Roman Period temple at Tebtunis, no less than six libation rituals were included in the daily temple ritual program. The deities were urged to drink the water offered to them in symbolic recognition of the rejuvenating power of the Nile: “Offering libation. Words spoken: May this water rejuvenate your body, may your majesty drink from the water. Offering libation. Words spoken: This libation is brought from Abydos, it came from the region of the Sea of Horus. May you drink it, may you live by means of it, may your heart be sound by means of it, the divine water to [fill?] your altar [with] the libation that I like.”

“The act of drinking the water provided a sense of purification from the inside, thus imbuing the ritual with a heightened spiritual significance. Moreover, allusions to the inundation were often made, as the pouring of the water was regarded as symbolizing the coming of the inundation, and the libation water was compared to Nun: “Hail to you, precious libation jar, which inundates Nun and Nut. Spell for presenting libation. Words spoken: Hail to you, Nun in your name of Nun. Hail to you, Inundation in your name of Inundation. Pouring libation to the altar. Words spoken: Hail to you, the Powerful, take to yourself the libation, which begot everything living. I have come to you, the vases are inundated, the jars filled with the flood, and the vases filled with the inundation for your Majesty.”

“Here the significance of libation is no longer merely purification; rather, it has been elevated to the level of cosmic rejuvenation by associating the pouring of water with the coming of the annual Nile flood. This metaphor, found in the Pyramid Texts, was of course very ancient: “O King, your cool water is the great flood that issued from you. You have your water, you have your flood, you have your efflux that issued from Osiris.” In sum, the overwhelming ritual significance of water was its affinity to the Nile flood: the rejuvenating power of nature. Whether the water was poured before the deities, or on the statues of the deities as an ablution, or drunk by the deities as a libation, merely expressed a variation of the same idea.”

Roman depiction of an Isis water ceremony

Milk Libation Images at Philae

Some of the massive reliefs on the temples on the island of Philae near Aswan in southern Egypt depict Ptolemaic pharaohs and other important religious officials offering libations to gods, often Isis and Osiris and their son Horus. Isma’il Kushkush wrote in Archaeology Magazine: In Egyptian mythology, Osiris was killed and dismembered by his brother Seth. Their sister and Osiris’ wife, Isis, managed to reassemble his body and he was brought back to life as the god of the underworld. The Egyptians offered libations, usually water or wine, to Osiris during rituals intended to symbolically aid in his rebirth. At Philae, depictions of this ritual include examples that show Ptolemaic pharaohs offering Osiris water in two small bottles, as was customary in Egyptian practice. However, others appear to show them offering Osiris libations of milk, which they pour out before the god from a situla, a long narrow vessel with a looped handle. This, Egyptologist Solange Ashby of the University of California, Los Angeles believes, was a distinctly Nubian practice. “What we see at these temples is this different type of libation, which is to pour out a stream of milk that goes over offerings laid out on an offering table,” she says. [Source: Isma’il Kushkush, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2021]

Egyptologists have debated for a century whether or not these scenes are intended to depict milk libations or offerings of wine or water. “I say this is milk,” says Ashby. She points to a scene inside the temple of Isis at Philae depicting Ptolemy VIII (r. 170–116 B.C.) offering a libation to Osiris, with Isis standing behind the god. “The hieroglyphs around him say this milk comes from the breast of the goddess Hesat,” Ashby explains, referring to a celestial cow goddess. Some scholars have argued that even if the depictions show milk libations, they must represent an Egyptian tradition. For Ashby, even though the depictions of the milk libation occur in Ptolemaic temples, the ritual is a purely Nubian practice. “I suggest they adopted it from Nubian worshippers,” she says. She points out that the earliest depictions of milk libations are found in Lower Nubia at the temple of Dakka, in a sanctuary that was built by the Meroitic king Arkamani (r. 275–250 B.C.). Milk libations are also depicted in royal funeral chapels farther south, in Upper Nubia, which is part of modern-day Sudan. At the temple of Musawwarat es-Sufra, for example, reliefs depict herdsmen preparing milk offerings for the Nubian lion-headed god Apedemak. But there are no such depictions in temples north of the first cataract, in Egypt proper.

Hieroglyphs at Philae’s temple of Isis refer to milk as ankh-was, or “life and power.” “Milk seems to be infused with this magical element of transferring life and power to the one who is deceased, much in the way that the breast milk of a mother keeps her infant alive and growing,” says Ashby. “There seems to be this connection in the mind of Nubians.” For the Nubians, then, milk would have been the ideal offering to aid in the rebirth of Osiris.

Milk libation rituals would have been performed during annual funerary rites for Osiris. Known as the Festival of Entry, this ceremony was held during the month of Khoiak, in the early fall, when the Nile flooding reached its peak. Gilded statues of Isis and Osiris were taken from the Isis temple at Philae to boats moored outside a structure known as the Gate of Hadrian. They were then rowed across the Nile to the island of Biga, where Osiris was thought to have been buried. There, at a sanctuary known as the Abaton, milk libations were offered to the god. Ashby notes that, until quite recently, milk played a central role in rituals surrounding death in Nubia. Within living memory, a widow would traditionally pour milk on her husband’s grave on the second day after his death, a distant echo, perhaps, of the milk libations offered to Osiris.

Sacrifices in Ancient Egypt

cat killing the demon Apep

In 440 B.C. Herodotus wrote that Egyptians were forbidden to sacrifice animals except pigs, bulls and bull-calves, if they are unblemished, and geese. In Book 2 of “Histories” he wrote:” Egyptians of whom I have spoken sacrifice no goats, male or female: the Mendesians [people that lived in the Mendes region alog the Nile] reckon Pan among the eight gods who, they say, were before the twelve gods. Now in their painting and sculpture, the image of Pan is made with the head and the legs of a goat, as among the Greeks; not that he is thought to be in fact such, or unlike other gods; but why they represent him so, I have no wish to say. The Mendesians consider all goats sacred, the male even more than the female, and goatherds are held in special estimation: one he-goat is most sacred of all; when he dies, it is ordained that there should be great mourning in all the Mendesian district. In the Egyptian language Mendes is the name both for the he-goat and for Pan. In my lifetime a strange thing occurred in this district: a he-goat had intercourse openly with a woman. This came to be publicly known. 47. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

:“All that have a temple of Zeus of Thebes or are of the Theban district sacrifice goats, but will not touch sheep. For no gods are worshipped by all Egyptians in common except Isis and Osiris, who they say is Dionysus; these are worshipped by all alike. Those who have a temple of Mendes or are of the Mendesian district sacrifice sheep, but will not touch goats. The Thebans, and those who by the Theban example will not touch sheep, give the following reason for their ordinance: they say that Heracles wanted very much to see Zeus and that Zeus did not want to be seen by him, but that finally, when Heracles prayed, Zeus contrived to show himself displaying the head and wearing the fleece of a ram which he had flayed and beheaded. It is from this that the Egyptian images of Zeus have a ram's head; and in this, the Egyptians are imitated by the Ammonians, who are colonists from Egypt and Ethiopia and speak a language compounded of the tongues of both countries. It was from this, I think, that the Ammonians got their name, too; for the Egyptians call Zeus “Amon”. The Thebans, then, consider rams sacred for this reason, and do not sacrifice them. But one day a year, at the festival of Zeus, they cut in pieces and flay a single ram and put the fleece on the image of Zeus, as in the story; then they bring an image of Heracles near it. Having done this, all that are at the temple mourn for the ram, and then bury it in a sacred coffin. 43.

See Separate Article: SACRIFICES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egyptian Religious Practices That Live On in Coptic Christianity

Coptic cross and Greek writing on older inscriptions at the Isis Temple in Philae

Saphinaz-Amal Naguib of the University of Oslo wrote: “Urbanization and globalization have profoundly changed Egyptian culture and prompted the abandonment of most religious practices belonging to the Egyptian lore. However, some aspects of Pharaonic religious practices can still be observed in Coptic Christianity. These practices are tied to the Coptic calendar, funerary rituals, visits to the dead, and mulids. [Source: Saphinaz-Amal Naguib, University of Oslo, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Egypt has been open to a number of foreign influences. One cannot, therefore, assert that customs and rituals derive directly and unaltered from Pharaonic times, and that they are exclusively Egyptian and Coptic. As mentioned earlier, traditions are hybrid and continuously adapted to changing contexts. What is important is not to assess the degree of indebtedness one culture has to another but instead to explore the significance, quality, and results of acculturation processes.

Coptic religious iconography offers many examples of themes and motifs that have been perceived as legacies from Pharaonic times. Such examples do not necessarily imply a direct, unbroken cultural lineage to ancient Egypt. Rather, they show cultural resilience and the power to accommodate various cultural influences within an Egyptian mould. Among the most known motifs are the representations of Maria Lactans, which bring to mind those of Isis with the child Horus; similarly, the figure of the holy horseman or warrior-saint slaying a dragon, devil, or snake with his spear echoes that of Horus fighting Seth, or killing Apophis or a crocodile.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024